‘Seinfeld’ Ended 25 Years Ago

The show about nothing has a big legacy.

NYT’s staff editor Maya Salam (“What’s the Deal With Adulthood? 25 Years Later, ‘Seinfeld’ Feels Revelatory.”):

I started watching “Seinfeld” when it debuted on NBC in 1989 and never stopped, watching and rewatching every episode relentlessly on various platforms, reading the scripts in my free time and annoyingly inserting quotes into conversation at every chance. (Apologies to all.)

When the show concluded 25 years ago on Sunday, just days before I graduated from high school, I and my fellow young “Seinfeld” aficionados gathered in front of the TV to say goodbye to Jerry, Elaine, George, Kramer and the many indelible side characters, like Yev Kassem (“The Soup Nazi”) and Marla Penny (“The Virgin”), who denounced them in a courtroom in the show’s polarizing finale. It was technically the end of an era, but for me, it was only the beginning of what would go on to inform every phase of my life.

[…]

It has consistently been framed as a comedy about four terrible people, with good reason. Jerry and his fellow misfits lied, cheated and stole. They were petty and shallow. They created a framework for “bad” sitcom characters that shows like “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” would embrace with great relish and success.

But they also presented an irreverent version of adulthood that I had never seen on TV or in life: a playful yet sophisticated world where grown-ups joked and laughed together and didn’t take themselves too seriously, even when everyone around them was being very serious indeed.

Most important, they openly mocked the notion that professional success, marriage and parenthood were the cornerstones of existence. For me, a serious child surrounded by serious adults — a child who was ostracized by those unable to categorize me, and who knew early that established paths to fulfillment would not apply — this revealed loads of possibilities.

“Seinfeld” outright questioned these constructs. In one episode, when Jerry and George are compelled to wonder whether they need to grow up, Jerry gets an explosive rebuke from Kramer: “What are you thinking about, Jerry? Marriage? Family? They’re prisons! Man-made prisons! You’re doing time.” In another, when George bemoans an awkward office interaction, Jerry, self-satisfied, responds: “I’ve never had a job.” (In a 1993 interview with Charlie Rose, Seinfeld said one benefit of being a comic was the ability to reject many facets of ordinary life: “You just don’t feel part of it, and that’s a good thing.”)

This refusenik sensibility is threaded through the entire series, and any attempt by the characters to sublimate themselves to social norms fizzled quickly and often in grand fashion. Particularly professionally, where opportunities and aspirations came and went: Kramer’s outlandish business ventures; Elaine’s fitful career in publishing; George’s corporate self-sabotage; even Jerry’s hope, in the show’s most meta subplot, to parlay his stand-up career into a successful sitcom.

Some of the funniest scenarios specifically skewered the absurdities of office jobs. In one episode, Kramer is mistaken for an employee after using a company’s bathroom and then keeps returning as if he works there. Wearing a suit and swinging a briefcase that contained nothing but crackers, he was a kid playing office; an impostor without impostor syndrome. Elaine’s professional prospects were subject to the whims of unreasonable, eccentric bosses, but her identity was never defined by her career. Instead her jobs and superiors acted as foils for her personality to flourish.

But crucially, after each of their many failures, the characters largely ended up just as they were before: fine, unbothered, unscathed and rarely dejected for long. This certainly had a precedent rooted in reality: When Terry Gross asked David in 1992 if the show’s early low ratings were demoralizing, he responded, “If the show got canceled, it didn’t make a difference to either one of us.”

[…]

Today — as cracks in the facade of hustle culture continue to spread; as a growing library of books and articles promote the value of rest and fun; as more people delay or forgo marriage or children — real life seems to be catching up with “Seinfeld.” Even from a less rosy perspective, with the realization that long-held images of adulthood may not be as attainable as before, the show has taken on a fresh relatability, offering new reasons for a little self-deprecating humor.

Frederic J. Frommer, WaPo (“25 years later, America still loves ‘Seinfeld’ but some hate how it ended“):

A quarter-century ago Sunday, 76 million people tuned in to the “Seinfeld” finale, saying goodbye not only to Jerry, George, Elaine and Kramer but also to a procession of angry bit characters, from the Soup Nazi to a library cop, who returned to the show to testify against them.

In an era before streaming and DVRs were commonplace, fans had to be glued to the finale live that spring Thursday night of May 14, 1998. In that sense, it was like the Super Bowl of sitcoms.

Larry David came back after a two-year hiatus to write the final episode, which ended with — spoiler alert — the four main characters sentenced to a year in jail for violating the “Good Samaritan Law” in a small Massachusetts town. The send-off got mixed reviews from critics and fans alike. Newsday called it “a terrible letdown.”

“Finales are hard, right?” Jeff Schaffer, the show’s executive producer that year, said in a recent interview. “Because it’s sort of a betrayal to the audience. You’re breaking up with them. They’re going, ‘You’re leaving me. Why are you leaving me? All I’ve done is love you.’ So you’re already operating in this potential atmosphere of resentment and sadness, because it’s gone, you’re gone.”

Or, as Post television critic Tom Shales wrote at the time, “According to just about every magazine on every newsstand in the country, we are a nation united in inconsolable grief over the impending demise of ‘Seinfeld,’ the NBC sitcom that ends its nine-year network run May 14.”

[…]

Set on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, it was often dubbed a show about nothing, but it was actually a show about everything: life’s daily ups and downs, irritations and challenges, albeit taken to absurd extremes, told through a quartet of self-absorbed 30-something friends.

Spike Feresten, a writer and supervising producer, recalled in an interview the guidance that David and Seinfeld gave the writers in one of his first meetings.

“‘We don’t want you guys to make up stories. We would prefer you guys tell us stories about what is going on in your life, specifically in New York,’” Feresten recounted. “‘Things that happened to you that haven’t left your mind, a moment that made you angry on a date and something you wanted to say, but didn’t have the courage to say.’”

One example was the 1996 episode “The Calzone,” in which George (Jason Alexander) makes inroads with his boss, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner (voiced by David), by bringing him a calzone for lunch every day from a local pizzeria. Schaffer, who co-wrote the episode with Alec Berg, said the plot line came right out of personal experience — to a point.

Writers had gone to “this little little Italian place, like a block away from the studio,” and “I order a sub, I pay the guy and as I’m about to put the money in the tip jar, he turns away,” said Schaffer, now an executive producer and director on David’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” “I’m like, I want to pull this back out and do it again. Well, I’m not going to do that, but George is going to do that.”

And so George did. And it backfired spectacularly.

Feresten’s “Soup Nazi” episode came about, he said, during a stalled story-ideas meeting with David and Seinfeld. David had a suggestion: “You just came from New York, right? Just tell us what’s happening in New York.”

“Well, you know, there’s this guy we call the Soup Nazi,” Feresten replied, and David immediately started laughing.

“What do you mean the Soup Nazi?” he asked.

“Everybody calls him the Soup Nazi because he has this very specific way of how he wants people to order soup,” Feresten said, explaining how customers would have to step aside after ordering.

“Or what?”

“Or you don’t get your soup. He takes the soup away and gives you your money back.”

“There you go,” David told him, laughing. “Do that as an episode.”

[…]

That magic formula had tens of millions of Americans on May 14, 1998, watching the “Seinfeld” finale, whose 41.3 rating nearly matched that year’s Super Bowl. In that final episode, Jerry and George land a sitcom deal with NBC, Elaine and Kramer (Michael Richards) join them on a trip to Paris, and it all goes wrong when the plane is forced to land in fictional Latham, Mass.

The foursome go into town and witness an obese man getting carjacked at gunpoint. They crack mean jokes about him — “Well, there goes the money for the lipo,” Jerry says — and are arrested for violating Latham’s “Good Samaritan Law,” which requires people to assist anyone in danger if it’s reasonable to do so.

David uses the ensuing criminal trial as a vehicle to bring back a host of characters — now character witnesses — who had roles throughout the show’s nine seasons, calling and flashing back to remind viewers of the main characters’ offensive behavior. The first witness, an elderly woman, testifies about Jerry stealing her marble rye after she buys the last one at a bakery. Viewers at home see a clip from that earlier show, where she yells for help as he wrestles the rye from her and shouts, “Shut up, you old bag!”

The judge’s name is Arthur Vandelay, matching the name of the company George once made up, Vandelay Industries, in an ill-fated attempt to fool the unemployment office. The courtroom is packed with spectators such as Jerry’s nemesis, Newman (Wayne Knight), who eats popcorn during the trial; Elaine’s former boss, J. Peterman (John O’Hurley); and former baseball star Keith Hernandez, who briefly dated Elaine and befriended Jerry.

[…]

After the jury finds the four friends guilty, the judge says their “callous indifference and utter disregard for everything that is good and decent has rocked the very foundation upon which our society is built.” Then he issues a one-year sentence. The series ends with Jerry doing a stand-up routine in front of fellow inmates, wearing an orange prison uniform.

Blowback followed. Seinfeld himself has had second thoughts about it all since.

“I sometimes think we really shouldn’t have even done” the finale, he said in 2017. “There was a lot of pressure on us at that time to do one big last show, but big is always bad in comedy.”

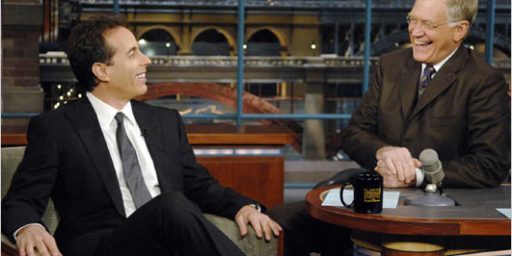

Louis-Dreyfus might have seen it the same way. “Thanks for letting me take part in another hugely disappointing series finale,” she joked on David Letterman’s last “Late Show,” in 2015.

Feresten, for his part, said he loved the “Seinfeld” finale. But he acknowledged it’s hard for a show to say goodbye.

“Your audience is going to be emotional when they realize there’s no more of these people we’ve grown to love, even though this show is famous for no hugging and no learning,” he said. “I don’t know if there was a way to win and make everybody happy. And perhaps that’s why it was just written to be another episode of the show, but also a way to kind of let you have one last visit with your favorite characters.”

The finale was definitely a disappointment in real time. In hindsight, it works very well as a clips show, not only giving every memorable one-shot character a curtain call but closure. At the time, though, it was an unsatisfying send-off to the main characters.

Ferensten is right, though, that fans are almost always going to be disappointed. The most-watched series finale ever, the February 28, 1984 M*A*SH “Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen” wrapped everything into a neat bow but was rather gloomy and depressing—fitting for a show set in a war zone, of course, but not great for a sitcom. Perhaps the most famous sitcom ending, the May 21, 1990 “The Last Newhart,” brilliantly brought back Suzanne Pleshette to reprise her character from The Bob Newhart Show. While a hilarious and unexpected gag, it literally rendered the entire series a dream. The other alternative, as in the May 6, 2004 Friends finale, “The One Where They Say Goodbye,” is fan service—finally giving the audience what they wanted all along with the top characters finally getting together, presumably to live happily ever after.

While I’m (vaguely) happy for actors who manage to find a gig where residuals happen, sitcoms have never been my thing. Never managed to sit through a single episode of this one, as far as I know.

But that’s why we have 3,754,456+ different entertainment channels on the tube, innit?

I did not like the finale in real-time, but have come to appreciate it.

The reprise of the show on Curb was fantastic (as well as all the jokes about the finale).

Series finales can be problematic.

Babylon 5’s finale, Sleeping in Light, was shot on the 4th season*, when there was every doubt there’d be a fifth season. When it was picked up by another network, JMS had to hurriedly do a season 4 finale, The Deconstruction of Falling Stars.

IMO, this makes for two series finales, and there’s an argument that Deconstruction is the better one.

Futurama was cancelled twice. So it has two formal finales: The Devil’s Hands Are Idle Playthings for the first cancellation, and Meanwhile for the second.

It’s set for a second revival, so it will need a third eventually.

*That’s why Ivanova is in it, though Claudia Christian left the show for season 5.

I have fried my brain watching TV sitcoms for years. My dad worked for Eastman Kodak when we lived in Rochester NY. Kodak was a sponsor of the Ozzie and Harriet program and he would ocasionally bring home scripts for the production and I would read along as the show played out.

I have been in love with Candice Bergen ever since I saw her on You Bet Your Life with Groucho’s daughter Melinda Marx when I was 10 years old. Needless to say I was a big fan of Murphy Brown. However if I saw the finale of that series it’s gone from my memory.

In the early 70’s on Saturday night it was M*A*S*H, All in the Family, Bob Newhart and Mary Tyler Moore.

My video habits were altered by technology when over the air VHF/UHF converted to digital. I never made the transition. I have never seen an episode of Friends or Bang. The only thing I watched on my ancient cathode ray tube video receiver were DVDs till the damn TV went dark a while back. I was just in Walmart the other day and saw a 24inch flatscreen on sale for $88. I may just have to pick one up. I’m tired of watching Star Trek: TOS on my new iPhone about 8 inches from my nose.

ETA: Groucho’s cigar smoking Duck made the show for me every week. Say the secret word!

SERENITY

NOW25 YEARS AGO !!!I have to be honest. I have never seen a single episode of Seinfeld. Guess what? Haven’t missed it either.

My point? I don’t know, other than it was wholly inconsequential to me. I doubt it was consequential to anybody else either.

@OzarkHillbilly:

The funny thing is: In my head, I heard that comment in a George Costanza voice, being said to Jerry, while they were both seated at Monk’s Cafe.

It is a moment in time.