Speaking of Reform

Let me point you to a reform proposal.

I would highly recommend this following post from my friend of many decades, and sometimes co-author, Matthew Shugart: Emergency electoral reform: OLPR for the US House. I should note that Matthew is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Political Science from UC Davis and is one of the foremost experts in the world on electoral systems.

His is a proposal for moderate proportional representation using open lists. I will define, below, the basics so that those who are perhaps unfamiliar will have a basis for understanding.

I think Mattew is correct that we are in a democratic emergency and the time to act is now.

I am not arguing for a change to PR only for the sake of the Democratic Party. In fact, my argument is that this is a way for Republicans to save their own party. The country needs functioning pro-democratic parties on both the center-left and the center-right. At the moment, it has such a party only on the center-left, and even that is a temporary ceasefire amidst a deepening internal division.

His basic assessment of the current party system is correct, in my estimation:

Basically, the point is that there are (at least) two “rights” and two “lefts” but currently only one party on the right and one on the left. And the emergency is that one of the “rights” has abandoned democracy and shown a willingness to accept political violence.

The need for PR is to let the free-market small-d democrats in the currently existing parties act independently of their more extreme wings. This is precisely what PR systems permit-each side’s extreme can be its own party rather than a wing of one majority-seeking party, without raising concerns over “spoilers” that arise under plurality elections.

I would very much recommend the whole thing.

BTW, I think that Congress could (although I don’t think it will) pass the reform. Article I, Section 4 states (emphasis mine):

The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators.

A Quick Primer on List-PR

In simple terms, proportional representation (PR) describes electoral rules that produce outcomes wherein the percentage of votes a party can get in the electorate results in that party getting roughly that percentage of seats in the legislature.

Hence, if the Me Party can get 10% of the vote it gets 10% of the seats (or, to pick the example with the easiest math, 10 out of 100 seats in a 100-seat chamber).

So a perfectly proportional system would produce results wherein %votes=%seats. Of course, the reality is that PR systems vary as to precisely how close to equal those two variables are but lack of perfect proportionality in a given outcome does not take away from the general principle.

There are a variety of reasons why a system might be more or less proportional, but I won’t go into that here. Instead, let’s consider the basics of list-based PR.

In list-based systems, open or closed (I will get to that in a minute), citizens vote in multi-seat districts (more than 1 seat) because you can’t proportionally allocate one seat.

List PR means a system wherein the parties submit lists of candidates to compete in the multi-seat district. Under Matthew’s proposal, we would convert the states into districts. So, my state of residence would be a district of 7. Each party would likely submit a list of seven candidates (hope springing eternal and all of that). Correction: his proposal would divide states in multi-seat districts of 3-5 seats (that does not change anything substantive in this post).

Citizens, it should be noted, still only get one vote apiece. They cast that vote for the list (closed lists) or for their preferred candidate on a list (open). More on that below.

If a party won 100% of the vote, they would get all 7 seats (but that isn’t going to happen). However, if they only won 40% of the vote, they would get ~40% of the seats (since 40% of 7 is 2.8 is a bit more complicated than just a basic calculation–the likelihood is that the part would win 3 seats in such a system or 42.9% of the seats).

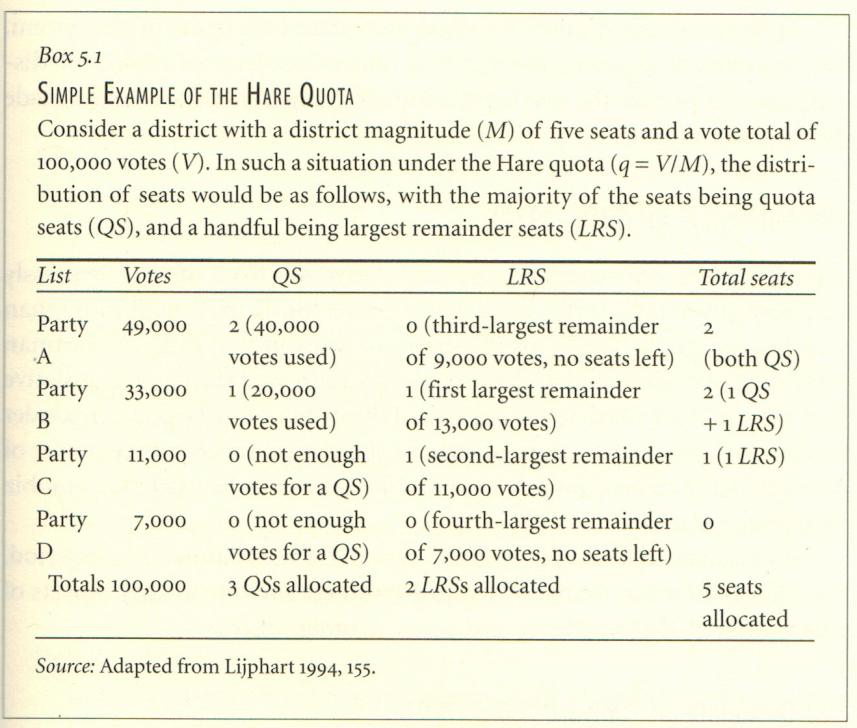

Allocation formulas have to be applied, and there are several to choose from (with D’Hondt, mentioned by Matthew, being the most prevalent). The example below is the Hare quota, which I think is the easiest to understand, although not widely used.

The Hare quota basically takes the number of votes cast in a district and divides it by the number of seats available. So each seat “costs” (the quota) votes equal to 1/M votes (with M being the district magnitude, i.e., the number of seats being contested).

For each quota a list wins, it gets a seat. Once all the quota seats are allocated if any seats have not been allocated then the party lists with the largest remainder of seats get those.

Here is an example spelled out from my 2009 book on Colombia:

Note that in this example:

- Party A won 49% of the vote and 40% of the seats

- Party B won 33% of the vote and 40% of the seats

- Party C won 11% of the vote and 20% of the seats

- Party D won 7% of the vote and no seats.

This allocation formula skew towards smaller parties, which would likely lead to more fragmentation of the party system. And that is perhaps not desirable (but is a whole other conversation).

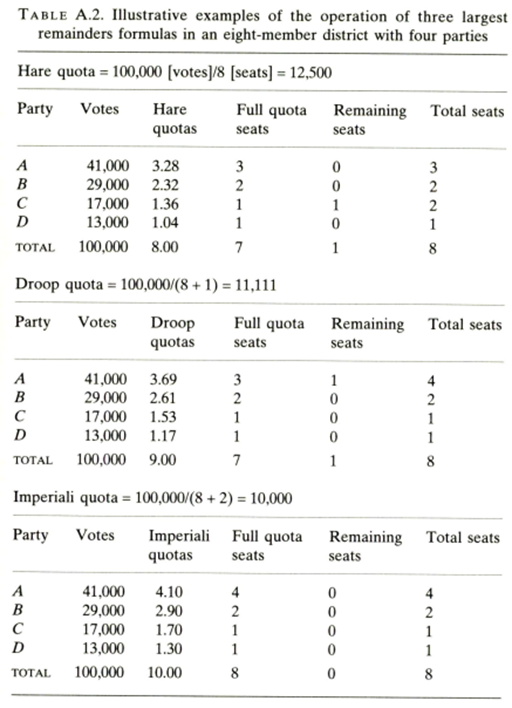

Here are some more example from Lijphart 1994, which show how minor changes to different allocation methods can make a difference :

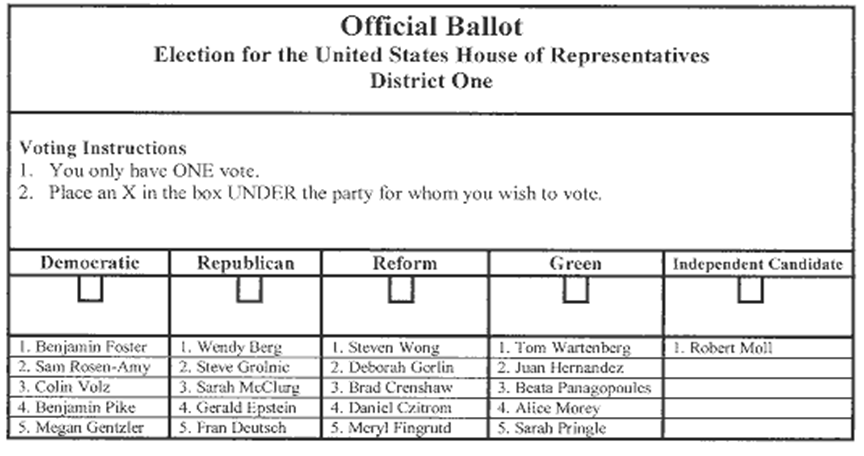

Now, a list is closed if the voter only has the option to vote for the party and not indicate candidate-specific preferences.

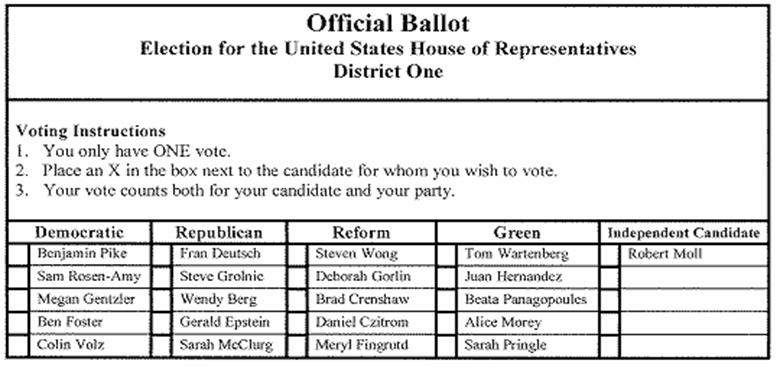

A potential ballot might look like this (a graphic I nabbed from Fairvote, I think, years ago but the link I have no longer works):

In a closed list the seats are allocated in order. So if the Democrats won 2 seats, Foster and Rosen-Amy would get those seats and the other three would be out of luck. The party controls the order and being 5th on the list is tantamount to “I ran for Congress and all I got was this lousy t-shirt” kind of situation.

An open list means you vote for your preferred candidate on that list:

The allocation of seats to the lists is the same, but the two elected Democrats would not necessarily be the top two on the list, but rather then two who received the most preference votes (maybe Pike and Foster, for example).

Hopefully this quick tutorial makes enough sense to help with understanding Matthew’s proposal.

Sign me up, anything is better than the current system. I’d welcome PR allocation of only EV in presidential races, but to include the house is a greater improvement. Though politically it would be an easier sell simply to focus on EV.

Past the matter that electoral reform is not a big issue at large, even among politicians (or especially among them), the great big impediment I see is that it would be very hard to change from a very simple system, first past the post, to a complex one.

I haven’t bet at a racetrack in over 25 years, but I vaguely recall the bets available. The one that pays least is betting on which horse wins, but that’s the easiest one (and the most likely to win). A better bet is to guess which horses come in first and second, and even better first, second, and third.

People who frequent racetracks naturally are interested in all this, so they learn to make the bets that pay more. Newbies and casual bettors go for who wins*. The problem in our little analogy is that everyone can vote, not just those interested in politics; and while not everyone votes, there are more casual voters than interested voters.

I’m not saying something like this isn’t worth doing. it is. And I’m not saying it’s not worth pursuing. it is. But like landing people on the Moon, it won’t be either easy nor cheap, and Apollo took under 9 years to reach its goal.

Get enough people in the House interested, including Pelosi, and get Biden interested, and something might happen, if a simple majority will suffice, and the filibuster is done away with.

*Or hand their money over to their experienced friend/relative, and share wins and losses.

I like it. I especially like “the party with the biggest remainder gets a seat” part of the algorithm. Easy to calculate and understand. It seems unlikely to produce a unintuitive result, too.

The problem, alas, is that this has to appeal beyond political scientists.

A Democrat-majority Congress isn’t going to push this system unless it’s confident that it will strengthen their likelihood of setting the agenda going forward. If they believe that, then Republicans will naturally cast it as a conspiracy to steal elections. There is, after all, momentum for that stance!

I just don’t see how one builds momentum to make this seem legitimate in our current climate. And, absent our current climate, there’s much less need.

@James Joyner:

More so that the problem concerning misrepresentation in the House has been defined as partisan gerrymandering for decades. That’s how a party can have 60% of the vote in one state and score only 40% of the seats.

There is far more awareness of that issue among the general public, never mind the portion interested in politics, and far more willingness for reform in some places.

@Kathy: But this is the answer to gerrymandering. If an entire state is one district, then there are no boundaries to argue over. Now, a large state like California might be seven or eight districts, but once you have proportional representation, it scarcely matters where you place the district boundaries.

@James Joyner: This is true and I (and I am sure Matthew) have no illusions that this is going to be discussed in Congress, let alone passed.

But what else should experts do than try and tell anyone who will listen what possible solutions exist to truly major problems. Maybe, eventually, enough people will be willing to understand.

Matthew is correct when he notes that our system cannot remain democratic if one of the two parties is not committed to democracy. And that requires dramatic action by the pro-democracy party when it has the chance.

I know your concerns in this general realm, but since a large chunk of Republican members of Congress are currently willing to encourage their followers that the current system isn’t legitimate, I am not sure what else can be done save dramatic steps. I do not see us as going back to “normal” (whatever that may have been).

A couple of things are unclear to me.

– This requires multi seat districts, so this means a greatly enlarged House?

– How are the party lists established? A sort of single party jungle primary? Anyone who wants to runs and the top 5 (or whatever) get on the list? Or does this somehow give more control to party leadership?

My thoughts are along the same lines as James Joyner.

But there are even more fundamental problems with this and similar proposals:

I think these proposals are overly reliant on a worldview focused on nationalized politics and political debates. They therefore wrongly focus on “national” solutions that won’t and can’t actually work in practice.

Our politics is highly nationalized in the sense of what people are interested in talking about and debating, but that does not change the actual distribution of political authority across the nation, nor does it diminish the central role of the state and state government in this and many other things in American life. The reality is that elections are run by the states. Congressional districts are determined by the states. The allocation of EV’s are determined by each state. Ballot access is determined by the states. Etc. Any major election reform will have to – at the very least – have buy-in by the states and state governments.

I don’t see how that can be construed as giving Congress the authority to unilaterally remake the entire country’s election system and Congressional representation. “Manner” would have to do a lot of work that I don’t think it can do.

The second point is about the legitimacy of the process. The assumption that the states will follow what Congress wants on this is completely backward in my view. Problem one with that assumption – as mentioned – is that Congress doesn’t have the authority. Problem two – a solution that depends entirely on one faction (ie. Democrats) to make what you want to happen will not be seen as any kind of “greater good” no matter how it’s dressed up.

Ultimately, solutions to our political problems – including systemic problems – can’t come from gambits and schemes that only look at federal action and national politics. Especially those which rely on questionable assumptions. We cannot shortcut the fact that America’s Constitutional system prioritizes place-based voting in states.

The easiest thing for Congress to do, which is actually within its authority, is to uncap the House and double or triple its size. That would actually ameliorate all kinds of problems to include House representation, electoral college representation, and gerrymandering.

Bigger changes will have to be incubated in the states to see what actually works. This is not something the federal government can mandate without a Constitutional amendment. And of course, with that, we are back to the collective power of individual states.

The desire for change to be an immaculate birth at the federal level is understandable

but doomed to failure, regardless of what we may wish or hope.

The other thing I forgot to mention is how are political parties have given up all authority for the tyranny of the supposed democracy of the primary system that you discussed in your recent post.

This is another area for reform since the major parties did not use to be this weak. Here I think that Congress and state governments have a lot more room to maneuver compared to attempting to force some kind of PR system on the states.

@gVOR08: Not necessarily a larger house. Only a house where everybody in the State votes for all the members–or a single party as the case may be. You can certainly enlarge the house too, but it’s not a requirement.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Oh, we’re in agreement on that. What’s best and what’s possible are often at odds in politics but the latter shouldn’t preclude advocacy of the former.

@gVOR08:

As noted in Shugart’s post, he prefers a larger House because of the Cubed Root Rule but it’s a separate issue. MMD is possible for all but the handful of states with just one Representative. Obviously, it would be more effective if there were 600 Representatives and thus fewer one-seat states but only marginally so.

@Andy:

Yes. One of the ironies of our system is that, by democratizing party nominations, we’ve actually made our overall politics more authoritarian.

I’m generally on board with this, though I prefer a slightly different PR package myself https://www.amazon.com/Democratic-Theory-Naturalized-Foundations-Distilled/dp/179362495X But I do have an objection to the characterization of a democratic reform program as required to

“let the free-market small-d democrats in the currently existing parties act independently of their more extreme wings.” In my view, PR is required so that the people in a jurisdiction can get what they want. That is, it doesn’t matter at all whether they are or are not “free-market,” Marxian leftists, or right wing nativists. Tying up democratic reforms with particular outcomes or types of economic views that people might have is a crucial mistake in my view.

Here are a couple of things that summarize the take in my (long, unfortunately expensive) book:

https://erraticus.co/2021/01/15/authentic-democracy-voting-populism-democratic-reform/

https://www.3-16am.co.uk/articles/democracy-naturalised?c=end-times-series&fbclid=IwAR0zL8rgm13cQ0jmuYPfaUaCCMbHeL5oVZvakh2Jryuo4JfP7pQYgI1Ps2Q

@Kathy:

Very hard indeed. In Canada there have been several provincial referendums on replacing first past the post with various flavors of proportional representation. All of the referendums failed, in part because of heated disagreement among the proponents of different flavors of proportional representation, in part because some people worried they wouldn’t have a representative more worried about answering to them than to their party, and in part because all the PR systems were more complex than first past the post.

Trudeau’s Liberal Party even ran partly on replacing FPTP with some sort of proportional system, and then decided against it because of lack of anything even remotely like agreement on what kind of system to replace FPTP with.

In Canada, most people seem to agree that FPTP is a poor system. But there is no agreement on what to replace it with. I suspect the same thing would happen in America.