Supreme Court To Rule On Constitutionality Of Stolen Valor Act

The Supreme Court will have another interesting First Amendment case on its docket this Term.

Back in March, the full 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Stolen Valor Act, which makes it a Federal crime to lie about having received a military honor, was an unconstitutional abridgement of speech under the First Amendment. That decision upheld a 2010 decision from a three judge panel of the Court that reached the same conclusion. Today, the Supreme Court agreed to accept the government’s appeal in the case, meaning the case is likely to be argued early next year at the latest:

The Supreme Court announced Monday that it will review whether a federal law that makes it a crime to lie about receiving a military honor violates free speech rights.

A sharply divided U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled this year that the Stolen Valor Act passed overwhelmingly by Congress was unconstitutional. The chief judge of the circuit, Alex Kozinski, said it would be “terrifying” to permit the government to decide which sorts of lies could be prosecuted.

(…)

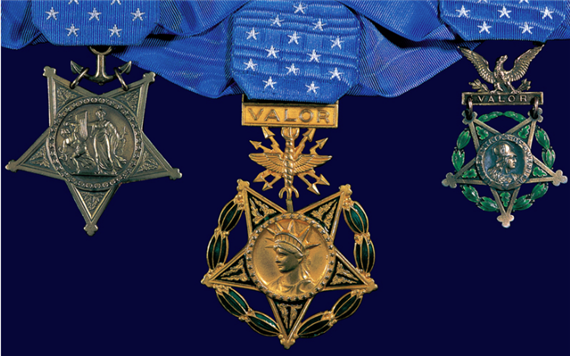

The Stolen Valor Act was approved by Congress to deal with an apparent proliferation of people falsely claiming to be military heroes. The act allows a fine and/or a six-month prison term for someone who “falsely represents himself or herself, verbally or in writing, to have been awarded any decoration or medal authorized by Congress for the Armed Forces of the United States.”

The penalty increases to a year in prison if the person lies about a Purple Heart, a Medal of Honor or another particularly high honor.

There’s no question Xavier Alvarez of Pomona, Calif., lied. After winning a seat on Southern California’s Three Valleys Municipal Water District board of directors in 2007, he introduced himself by saying: “I’m a retired Marine of 25 years. I retired in the year 2001. Back in 1987, I was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. I got wounded many times by the same guy.”

None of that was true. Alvarez pleaded guilty on the condition he would challenge the law as unconstitutional. A panel of the 9th Circuit agreed with him that it was, and the full court refused to reconsider the panel’s decision.

“If all untruthful speech is unprotected … we could all be made into criminals, depending on which lies those making the laws find offensive,” Kozinksi wrote. “And we would have to censor our speech to avoid the risk of prosecution for saying something that turns out to be false.

“The First Amendment does not tolerate giving the government such power.”

Lyle Denniston notes that this is yet another example of what seems to be a new interest in First Amendment cases at the Court:

With the Supreme Court newly active in deciding pleas to put some forms of free speech outside of the protection of the First Amendment, the Justices on Monday took on another such issue: the power of Congress to ban mere false statements, in a test case on the constitutionality of the so-called Stolen Valor Act of 2005. That law makes it a federal crime to falsely claim that one has received a military medal or decoration; punishment is more severe for such claims when a major decoration like the Congressional Medal of Honor was involved.

The Court in the past two Terms had turned down attempts to put expressions of violence outside of the free speech clause’s protection. The new issue is whether a lie, without any other factor, can be banned without violating the First Amendment. The Court has made conflicting comments over the years on whether a false statement, by itself, lacks constitutional protection. Such differing remarks have come mainly in cases involving false statements that are challenged in libel or defamation lawsuits.

There’s no question that Alvarez lying about having received America’s highest military honor was fairly despicable, but as Judge Alex Kozinski said in his majority opinion in March, the fact that it was a lie doesn’t necessarily mean that Congress can make it a crime:

Even if untruthful speech were not valuable for its own sake, its protection is clearly required to give breathing room to truthful self-expression, which is unequivocally protected by the First Amendment. See New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 271-72 (1964). Americans tell somewhere between two and fifty lies each day. See Jochen Mecke, Cultures of Lying 8 (2007). If all untruthful speech is unprotected, as the dissenters claim, we could all be made into criminals, depending on which lies those making the laws find offensive. And we would have to censor our speech to avoid the risk of prosecution for saying something that turns out to be false. The First Amendment does not tolerate giving the government such power.

Moreover, as I noted back in March, it’s entirely unclear what it is that Alvarez did wrong here in a criminal sense:

It’s important to note the context of the lies. He didn’t tell them as part of an effort to get elected, he didn’t tell them in order to persuade people to support his position on a particular issue, he didn’t tell them in order to achieve some kind of monetary gain. They were just, as the Court describes them, “bizarre lies” made more bizarre by the fact that determining whether or not a particular person has won the Medal Of Honor is a fairly easy task. There’s no real explanation for why Alvarez did it, but it is fairly obvious that nobody suffered any actual harm as a result of his lies, If they had, then Alvarez could have been prosecuted for fraud, or any other of a number of criminal offenses involving deception being used to deprive people of their property. That didn’t happen in this case, though, and Alvarez’s lies were obviously found out fairly quickly.

Fraud and defamation have never been entitled to First Amendment protection, but there’s no alllegation of either of those in this case for a very simple reason. In order to sustain such a claim, the false statements had to have been accompanied by real, quantifiable damages suffered by someone. No such damage occurred merely because Alvarez lied about having received a medal at the meeting.

It will be interesting to see how the Supreme Court rules on this. While the issue is a sensitive one, it’s worth noting that the Court’s recent First Amendment cases have all been either unanimous or nearly unanimous, and all of them have ruled in favor of protecting the speech. If that pattern holds here, the Stolen Valor Act is likely to suffer the same fate it did in the Ninth Circuit. Which is exactly how it should be.

This is the key part of the argument – as you say, just plain lying for the sake of lying is protected, but fraud is a different story. The issue of damages is important, but (IMHO) not as all-consuming as you seem to imply. There are specific, tangible benefits to being the legitimate possessor of certain military awards… the MoH, of course, has a number of bennies, as does the Purple Heart. And having certain campaign ribbons qualifies a person as a ‘combat vet’, and can affect your consideration for VA services and civil service jobs. I think the case will turn on the point of whether or not claiming possession of such an award implies fraudulent intent, and whether such intent can be outlawed. Claiming ownership of lesser awards that have no out-of-service impact is probably protected speech, but there’s an argument to be made about things like the MoH, that demonstrably affect the way people treat you, even if you don’t specifically _ask_ for that treatment.

@legion:

If Alvarez had received or accepted special benefits because of his false claim, then there would be fraud. if he’d tried to obtain the same from a government entity, then he’d have serious legal problems related to defrauding the government.

The reason the damages issue is important is that, without the existence of a person or entity that has suffered a loss due to reliance upon what turned out to be a false representation, then there can be no fraud as a matter of law in either the criminal or civil sense of the word.

@legion: Aren’t there a lot of claims that would come with intangible benefits? As shameful as falsely claiming to have won the Medal of Honor may be, I’m not seeing the need to criminalize it. Seems to me the existing fraud statues should catch anything worth prosecuting.

Mea culpa – I misread the part that said he made the claim _after_ he got elected, rather than during his campaign.

@legion:

I’m not at all certain that lying during the course of an election campaign would be considered actionable fraud.

@Doug Mataconis:

I’ll admit, it’s sketchy, but I can at least see the skeleton of an argument. Candidates lie all the time about what they’ll do once they get elected, but lying about objective facts in the process of “selling a product” would probably at least get a hearing, if not a decision.

@David M:

That seems to me the biggest argument against laws like this, but duplicating a law that just isn’t enforced properly/consistently doesn’t seem to stop new ones from getting passed…

@David M:

Agreed. I’d also think that anybody campaigning on the grounds of being a Medal of Honor winner would be susceptible to fact-checking. It’s not commonly awarded and should be a matter of public record. Getting caught in a lie that outrageous would tank somebody’s campaign.

I’d think that the Supremes would rule unanimously to strike the law.

If the 1st Amendment protects only speech that is agreeable to us, then it protects nothing at all.

Donald,

I disagree 😀 (I think you see where I’m going there…..)

If the Supremes don’t decide in favor of protected speech, Fox News my have to declare bankruptcy.

If you can tell a little white lie and its o.k. why does congress want to hand baseball players over steroid use when he says he didnt but they think he did?