Surviving the Tsunami – What Sri Lanka’s Animals Knew that Humans Didn’t

Slate has an interesting Explainer entitled “Surviving the Tsunami – What Sri Lanka’s animals knew that humans didn’t.”

Reports from Sri Lanka after Sunday’s tsunami say that despite the enormous number of human casualties—116,000 deaths and rising, at last count—many animals seem to have survived the tidal wave unscathed. At Sri Lanka’s national wildlife park at Yala, which houses elephants, buffalo, monkeys, and wild cats, no animal corpses were found on Wednesday. (Yet according to Reuters, the human devastation there was as tragic as elsewhere: Only 30 of the 250 tourist vehicles that entered the park on Sunday returned to base.) Did Yala’s animals sense the oncoming tsunami and flee to safety?

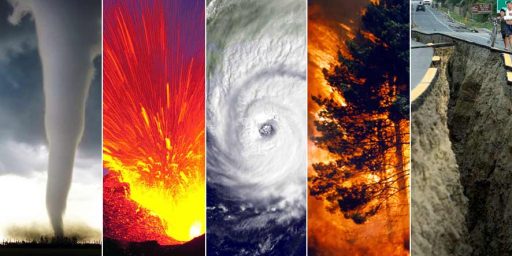

There’s a good chance the wildlife knew trouble was on the way. History is littered with tales about animals acting weirdly before natural disasters, but the phenomenon has been hard for scientists to pin down. Sometimes animals get crazy before a quake, sometimes they don’t. Here’s what we know: Animals have sensory abilities different from our own, and they might have tipped them off to Sunday’s disaster.

First, it’s possible that the animals may have heard the quake before the tsunami hit land. The underwater rupture likely generated sound waves known as infrasound or infrasonic sound. These low tones can be created by hugely energetic events, like meteor strikes, volcanic eruptions, avalanches, and earthquakes. Humans can’t hear infrasound—the lowest key on a piano is about the lowest tone the human ear can detect. But many animals—dogs, elephants, giraffes, hippos, tigers, pigeons, even cassowaries—can hear infrasound waves.

A second early-warning sign the animals might have sensed is ground vibration. In addition to spawning the tsunamis, Sunday’s quake generated massive vibrational waves that spread out from the epicenter on the floor of the Indian Ocean’s Bay of Bengal and traveled through the surface of the Earth. Known as Rayleigh waves (for Lord Rayleigh, who predicted their existence in 1885), these vibrations move through the ground like waves move on the surface of the ocean. They travel at 10 times the speed of sound. The waves would have reached Sri Lanka hours before the water hit. Mammals, birds, insects, and spiders can detect Rayleigh waves. Most can feel the movement in their bodies, although some, like snakes and salamanders, put their ears to the ground in order to perceive it. The animals at Yala might have felt the Rayleigh waves and run for higher ground.

Why would they instinctively flee to higher ground—the safest place to be in the event of a tsunami? Typically, animals scatter away from a place where they are disturbed. So, in this case, “away” may have meant away from the sea, and incidentally, away from sea level. Or maybe it’s not as accidental as all that. It’s easy to imagine that one of evolution’s general lessons is: If the ground beneath your feet starts moving, move up and away as fast as you can.

What about humans—where were our red flags? Humans feel infrasound. But we don’t necessarily know that that’s what we’re feeling. Some people experience sensations of being spooked or even feeling religious in the presence of infrasound. We also experience Rayleigh waves via special sensors in our joints (called pacinian corpuscles), which exist just for that purpose. Sadly, it seems we don’t pay attention to the information when we get it. Maybe we screen it out because there’s so much going on before our eyes and in our ears. Humans have a lot of things on their minds, and usually that works out OK.

Interesting.

Isn’t is also possible that the initial, fragmentary reports of “no anumal corpses” are exaggerated? Everything I’ve seen refers to this one Sri Lanka report. What about Indonesia? Thailand? India?

I’d have a little more confidence in this idea if some animal population studies actually confirmed that the numbers of animals hadn’t changed. Until then I’ll suspect that hungry people scavenged the dead animal carcasses for use as food. Can you say road-kill?