The DJIA and a Potential Trade War

The DJIA (and other markets) are not too happy about all of this trade war talk.

Earlier this year, I had intended to write a post to admit that I was wrong about an assumption that I had had about the Trump administration, to wit: that he had not created volatility in the stock market (something I had assumed would happen given his stated policy preferences). I was thinking about writing this post in January, right before we saw the market engage in some correction behavior. Between not always having the time to write that I would like, and given that the market was starting to deviate from its recent pattern, I never wrote that post.

Earlier this year, I had intended to write a post to admit that I was wrong about an assumption that I had had about the Trump administration, to wit: that he had not created volatility in the stock market (something I had assumed would happen given his stated policy preferences). I was thinking about writing this post in January, right before we saw the market engage in some correction behavior. Between not always having the time to write that I would like, and given that the market was starting to deviate from its recent pattern, I never wrote that post.

The last month has brought me back to my original position: Trump’s economic vision, if even partially implemented, is not something that markets want to see.

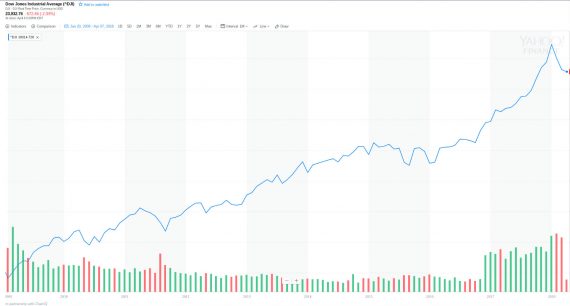

If one looks at the first year of the DJIA under Trump, there is certainly plenty to see that the President and his supporters would want to brag about. And, indeed, Trump has been known to do so.

Of course, any honest assessment of the DJIA would have to also note the longer-term trend since January 2009:

While I think both credit and blame given to presidents in terms of the markets is almost always over-simplified, there is something to be said about long-term trends of a given presidency, as well as looking at the basic context. Hence, it is noteworthy that the long-term trend line here is growth, which undercuts that notion that Trump administration did anything policy-wise upon its assumption of office to make the last year or so of growth happen. Trump inherited a very strong economy–perhaps not as strong as we might like, but a strong one nonetheless. It is truth at the upward slope of the DJIA during the first year of the Trump administration is steeper than that in the Obama years, and certainly part of that is perception of Trump as pro-business, his curtailing of some regulations, and anticipation of tax cuts (the latter of which is a clear policy linkage to the administration). Any analysis of the the last decade would have to take into account the Great Recession and the recovery as part of a broader trend.

In terms of major policy shifts in regards to the economy, however, Trump did not make any significant moves that comported with his campaign rhetoric, until February 26th, when he stated

I want to bring the steel industry back into our country. If that takes tariffs, let them take tariffs, okay? Maybe it will cost a little bit more, but we’ll have jobs. Let it take tariffs. I want to bring aluminum back into our country. These plants are all closing or closed.

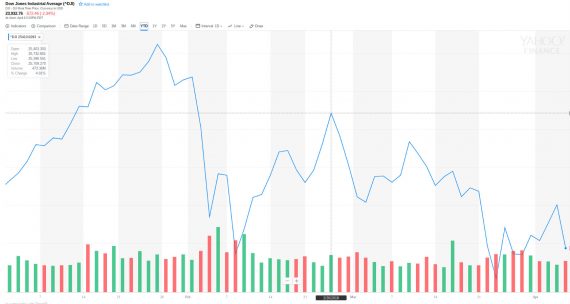

Note the DJIA since that time:

It is fair to note that the market engaged in some corrective behavior in January (as the upward trend was not going to maintain itself forever). That correction was linked to the possibility that the Fed would increase interest rates as well as concern that the employment rate was going to start putting pressure on wages (and hence effecting profits). Or, at least, that was the discussion in the financial press.

It is fair to note that the market engaged in some corrective behavior in January (as the upward trend was not going to maintain itself forever). That correction was linked to the possibility that the Fed would increase interest rates as well as concern that the employment rate was going to start putting pressure on wages (and hence effecting profits). Or, at least, that was the discussion in the financial press.

Regardless, the point of the post is simply to note the havoc that Trump’s comments on tariffs and trade wars has created in the market (and, again, one can see this in various global markets as well). We are now in a cycle of Trump making threats, and China responding. At the moment, this is mostly rhetorical, so one can imagine what it will look like if a full trade war is started. If one looks at the news for most of those valleys, one will find a statement by either the Trump administration or the Chinese government helping to drive them.

Several questions occur: is this what a “business savvy” president looks like? Is this, in any way, Republican orthodoxy on trade?

And, I would note what should be obvious: if there is a trade war, it will hit not just investors, but consumers. Tariffs will result in a far bigger tax increases (in terms of the price of goods) on average Americans than they will ever see in tax cuts from the law passed last year. (Indeed, if Chinese tariff’s come to fruition, areas of the country who voted for trump will be hit hard in terms of jobs and production, see WaPo: China’s retaliatory tariffs will hit Trump country hard).

I expect that Trump thinks that wild threats will lead to some sort of compromise with China and others on trade. But, of course, even modest tariffs will make the price of goods go up at WalMart.

There is no reason to assume that adopting abandoned trade policies from a century (or more) ago is a good idea. Rather, this is all standard populism: reckless application of half-baked policy notions without any kind of systematic plan. It is the same style as Hugo Chavez in Venezuela (and that certainly turned out nicely).

If you have a parrot who can mimic five phrases, that does not mean the parrot is Shakespeare. The parrot never becomes Shakespeare. He never becomes anything, he is all he is ever going to be. He’s a parrot, why would anyone expect a parrot to be anything more than a parrot?

Trump has slogans, bumper stickers, catchy phrases. He parrots those catch phrases. A surprisingly large number of people (46%) actually think that the kind of facile, superficial baloney their senile great-uncle spews at the Thanksgiving table after four beers is a prescription for running the executive branch of a superpower.

The first clue should have been Trump’s insistence that everything would be easy. Health care? Easy. Middle East peace? Easy. Foreign trade? Easy. Trump’s the kind of jackass who’d go to MIT and tell them to solve transportation problems by inventing faster than light travel. See? There’s a solution! Easy!

Every single job ever looks easy to people who don’t know anything. And they are always wrong.

I believe the good market performance in Trump’s first year, despite nothing really having happened until the tax bill, was a demonstration that many investors actually believe Republican nonsense about taxes, and regulation. And nothing that happens will convince them otherwise.

@michael reynolds:

I roll my eyes when people indicate their approval of a politician by saying “he (or she) tells it like it is.”

By that they really mean, ‘I like it that he (or she) doesn’t care about political correctness, being informed or analytical, because that sh** is not how I run my household or conduct my affairs.”

There’s your 46% right there.

Frightening traders into liquidating their long positions is likely to set the stage for a significant rally. This turbulence was inevitable when speculators are net long one million contracts since November 2016. All positions are unwound and this is no different.

Rubbish. We’ve been in a trade war with China for twenty years. Balancing the interests of workers and consumers, many times wearing both hats simultaneously, is difficult. But the current path is unsustainable.

@Guarneri: Let’s just say you have a rather expansive (and non-standard) definition of the term “trade war.”

@Steven L. Taylor: It’s a pretty straightforward concept. Trade war is when one country models its policies to drain demand from another for domestic benefit. This had been the Chinese model for decades, and it’s been tolerated by American elites because the policy coincides with their own class war on workers.

Some elites have now recognized that allowing that trend to continue deprives them of healthy working-class prey, as Veblen wrote in Theory of the Leisure Class, and are pressing to halt the process in a way which won’t impair their own predation.

@Ben Wolf: That is the kind of definition that isn’t helpful, as it basically defines away regular practices as “war.” I get where you are coming from, but I would expect that you would understand that “trade war” does not refer to that type of phenomenon, but rather to a purposeful disruption of the existing equilibrium of trade by parties using escalation to punish the other and gain a short-term upper hand. It typically revolves around tariffs and other limitations of access to markets.

@Steven L. Taylor: The definition you’re using limits “trade war” to a short-term, extraordinary phenomenon. In other words, it assumes trade has a natural, mutually beneficial equilibrium toward which it will gravitate unless acted upon by an outside force.

“Trade war” is the natural state among capitalist economies which typically suffer from lack of demand and excess capacity. Just as the British smashed the Indian textile sector to create a new market for domestic manufacturers to export into, taking action to punish a trading “partner” is a tactic in an ongoing conflict rather than initiation of hostilities. Donald’s wealthy backers see Chinese behaviors as interfering with capital accumulation and want a shift in tactics from diplomatic to economic. Adam Smith discussed this very phenomenon regarding the “home bias” of investors.

@Ben Wolf: I am not assuming that trade is natural or mutually beneficial.

I am stating that if your definition of “trade war” is “trade” then there is no point in having two terms.

@Ben Wolf: @Steven L. Taylor: To be more precise, if you have specific set of trade activities (regardless of whether one would assess them as just) you still have “trade.” A “trade war” would occur due to some aggressive change in that condition called “trade” such as I noted above.

I get that you do not think that the structure of capitalist global trade is just. Without agreeing or disagreeing, that is a different discussion.

@Steven L. Taylor: I haven’t yet discussed this issue in relation to justice. My previous comments are my opinion of how the system functions without regard to its virtues or lack thereof.

Trade in early capitalist society was run according to primitive bullionist principles for the purpose of capital accumulation. This later transformed into what is popularly known as mercantilist policies (which extended well beyond trade exchange itself into social welfare.) This phase resulted in sufficient capital formation to induce overproduction, unemployment and social discontent, leading to the imperialist phase in search of new markets.

Within each phase actors were attempting to disrupt their strategic adversaries through war, protectionism, political manipulation and alliance systems (like the TPP). “Trade” outside the capitalist paradigm becomes “continuous trade war” within it because the nation that secures an advantage in controlling capital flows gains socially and technologically, while the middle class owning the capital gains wealth and influence. All the incentives align for conflict, and there has never been a point at which any country you can name was not levying tariffs and sanctions against somebody else.

@Ben Wolf: Ok, so your view is that all trade is war. All well and good, but unhelpful linguistically in this conservation.

Really, you have to know what I am trying to say and you have to know what why the phrase in question is being deployed in regards to the potential of escalating tariffs between the US and China.

@Steven L. Taylor: No, trade within the capitalist paradigm is war. Trade outside can just be trade.

You wrote ‘A “trade war” would occur due to some aggressive change in that condition called “trade”. . . .’ I don’t disagree with you. I’m simply arguing that aggressive change is the norm within the current economic system and reject the idea that because this is a normal condition it can’t therefore be called war. Nobody criticizes Hobbes for describing pre-state societies as the “war of all men against all men” on the basis that because war was normal it isn’t a linguistically useful term. Everybody understands what Hobbes meant.

In the same way that absence of society in Hobbes “natural state of men” generated continuous conflict, capitalist systems generate instability in the course of normal function.

@Ben Wolf: I almost made a Hobbes reference earlier in the thread.

But, of course, plenty of people criticize Hobbes’ view that the state of nature is a state of war, Montesquieu and Rousseau do. Locke’s theory of the state of nature is a critique of Hobbes.

But that is all a digression.

I think we have hit the point at which we either agree to disagree or, perhaps more accurately, agree we are applying different paradigms to the discussion.