The Tip O’Neill Era and Why Governing was Easier

A reminder of how things (specifically the party system as a whole) have changed.

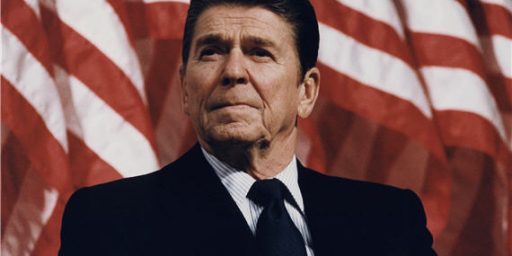

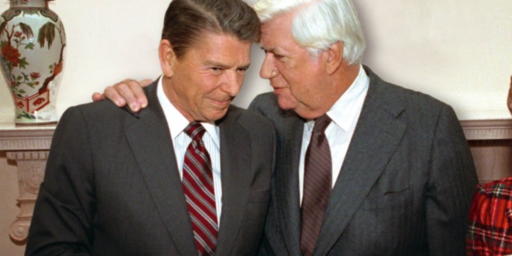

I often see it stated in any number of places, to include a passing reference in James Joyner’s post* about Speaker of the House fantasies, about how politics in Washington used to be different and how Speakers of the House like Tip O’Neill (D-MA) could cut deals and govern.** Indeed, it is not unusual to hear how ol’ Ronnie Reagan and Tip could have a beer together and hash out some compromises.

Oh, the joyous bipartisan past!

Now, it is certainly true that there was legislative activity in the 1980s that would be unthinkable today (including the dreaded “amnesty” bill that Reagan supported and signed not to mention a number of tax increases to go along with a number of tax cuts). But I think a lot of looking back ignores a number of key factors, not the least of which is that the pre-1994 party system was simply different.

I have written before about the transformation of the party system, in terms both of parties in the Congress, but also to the general process of moving to a Republican Southeast in particular (which is part of a broader sorting and polarization process nationally). It is important to always remember that one of the results of Reconstruction was the advent of the solid Democratic South that persisted for over a century (with some caveats as per some of the links below). It is also important to remember the power of the New Deal over national politics, which helped reinforce a lot of pro-Democratic voting during much of the post-WWII period (the combination of which led to Democratic dominance in the House for much of the 20th Century–see the second link below for a chart):

- US Party System Evolution

- Partisan Control in the Congress

- More on the Evolution of US Party Politics

It is important to stress that the 1994 elections (the “Republican Revolution”) were an important line of demarcation in the party system (meaning the overall configuration of party strength in the country, including geographical sorting and increased polarization). Yes, as the links above note (especially the third one) the overall shift is not utterly uniform over time, location, and office, but there is still a pretty dramatic change to national politics in the aftermath of 1994 (which takes some time to fully take hold–again, see the third link as it pertains to state-level politics).

At ant rate, what about the Magical Tip O’Neill and his ability to Get Things Done? How did he do it? What master of bipartisan negotiation and common sense good governance back in the Good Ole Days did he possess that allowed him to find a way to do what current politicians seem incapable of doing?

Well, let’s start with the fact that during his tenure as Speaker from 1977 to 1987 that he had, on average, 99.4 seats more than the Republicans and that within his own caucus he had an average of 49.2 seats above the needed 218 majority to pass legislation.***

Yes, you read that right–and let me stress that despite the fact we are dealing here with very basic arithmetic and I knew roughly what to expect, I have double-checked myself multiple times because the numbers are just nuts in comparison to the current era.

Here are the seat counts (and some other info) as pulled from the House and Senate web sites:

| Democrats | Republicans | Seat Differential | Seats Above Majority | Senate | ||

| 95th | 1977-1979 | 292 | 143 | 149 | 74 | D +34 |

| 96th | 1979-1981 | 278 | 157 | 121 | 60 | D +17 |

| 97th | 1981-1983 | 243 | 192 | 51 | 25 | R +6 |

| 98th | 1983-1985 | 269 | 166 | 103 | 51 | R +10 |

| 99th | 1985-1987 | 254 | 181 | 73 | 36 | R +6 |

Keep in mind that in 95th and 96th, Carter was President, and hence there was unified government and then from 97th-99th, Reagan was president and we had divided government (to include, as noted in the table, a split Congress).

The 97th Congress was Reagan’s first two years in office, and it is worth remembering that Reagan whipped Carter in the Electoral College, 489-49 (and 50.75% to 41.01% in the popular vote****) so it stands to reason that Congress might be somewhat cooperative in the afterglow of that election.

Now, the most fundamental point I want to make is that the Democratic caucus that O’Neil oversaw during that period of divided government was a broad coalition of liberals, moderates, and conservatives. There was a lot of room to make deals within the party (and a lot of votes to play with). This also meant that individual candidates fearing being primaried for not toeing the party line was just not the issue it is now. Indeed, with that many seats in the majority party is was quite easy for any given member to vote “no” against something that the party wanted to pass, but that they couldn’t defend back home, because the vote simply wasn’t needed. Put another way: with a large majority there is room for leadership to protect individual members.

There is also room in such a situation for members of the minority party to cross over without the kinds of political repercussions that would be the case now. Further, if you were a Republican during this period of time you did not think that you were going to take over the chamber in the next two years because, well, look at the margins! The entire strategic environment was radically different for O’Neil’s Democrats than Pelosi’s (or McCarthy’s GOP).

In other words, while it is the case that O’Neil was a skilled politician, and moreover he did have to cut deals with a GOP Senate and White House, he had a very, very different House majority caucus to work with (and a wholly different electoral dynamic influencing individual member behavior).

Not only was it radically easier to build legislative coalitions under those conditions, but it also meant that it was impossible for a small number of House members to derail major legislation. Indeed, O’Neil was in a position wherein he could marginalize uncooperative members by influencing committee assignments and whether money flowed to certain districts or not. This is simply a lot harder, if not impossible, with the margins we now see in the House.

Also, it matters when your party is confident it will retain majority status for the long haul (the Dems did for decades) as opposed to the very real likelihood that majority control might change after any particular two-year cycle.

To restate the basic thesis as clearly as possible: the Democratic majorities in the House that Speaker O’Neill managed were far different from majorities either party has seen in recent decades. The sheer number of seats coupled with the more ideological diversity within the caucus made for a very different and, quite frankly, easier, legislative environment to navigate. Legislative activity is about coalition-building, not just to elect leadership, but for every single piece of legislation. The more partners one can work with, and the more configurations that can be constructed, the more pathways a party leadership has to create acceptable outcomes.

So, while it is definitely true that O’Neil had to manage a large caucus in the context of both the post-Watergate Era and the Reagan Revolution but he also had a lot more maneuverability than more contemporary Speakers have had (not to mention a more functional Senate). More to the point, it is less that the era was more bipartisan, but that the Democratic caucus already had built-in compromise because its caucus encompassed left, center, and right.

*To be clear, the purpose of this post is not to call James out, it was just his mention of O’Neil tripped a wire in my head about something I have wanted to note for some time.

**Although in contrast to the way this era is often discussed, I found this 1982 column by Michael Barone in WaPo to be amusing: Tip O’Neill Is No Bumbler given that the premise of the piece is based in the fact that some had been calling O’Neil a bumbler, rather than the paragon of reasoned getting-things-done he is often cast as in the press these days.

***For comparison, Pelosi had +35 in the 116th Congress (2019-2021) and a 17 votes above majority and +10 with only 4 seats she could lose in the 117th.

(Really, even considering unified government, the legislative achievements of the 117th Congress are a testament to hard work and effective leadership across the Congress and into the White House).

****Independent John Anderson won 6.61% of the vote and other third party candidates got 1.62%. Carter was not very popular, shall we say.

@Steven

Indeed, my passing mention is this:

But, yes, we forget how overwhelming the numbers were during his tenure. Democrats held uninterrupted majorities from sometime during the Eisenhower administration until the Gingrich “revolution” in 1994.

Along with this are the major changes to how legislation is actually crafted in Congress which was much different then than today. Congress today operates much more like a parliamentary system for the crafting of legislation – meaning that legislation is written by a handful of leadership – often in secret- and then presented as a fait accompli to the membership with minimal debate or opportunity for further development and amendment. This is in stark contrast to how the system is designed to work, with the bulk of legislative work taking place in committees with a much more open and iterative process.