The War Drags On

Not only has the war changed, but so have the combatants.

The Russia-Ukraine War is in its second phase of slower, more protracted violence. The announcement of an agreement between the combatants for the release of Ukrainian grain exports through the Black Sea is a definite sign that we are no longer in the first phase, the period of liquid possibilities, and the anticipation of quick results, that occurs at the beginning of every conflict. Attritional war is now such a fact of life in Ukraine that Russia and Ukraine can reach understandings like these, while the shooting, bombing and shelling continues unabated. We also see the second phase in the reduced prominence of news stories from the war. Where the invasion once dominated the headlines, it has clearly dropped in priority, as competing crises (inflation, political instability in the United States, etc.) now appear more frequently “above the fold.”

What also happens in these secondary periods of conflicts is the increase in the stakes for both combatants. Ukraine, NATO, and the United States have all indicated that too many have died, fled their homes, or have ben tortured or raped for there to be any acceptable compromise. Even the full withdrawal of Russian forces may not be enough, since the perilous status quo ante is what led to the Russian invasion in the first place.

As wars progress, not only does the nature of the war change, but so do the combatants themselves. Before the invasion, the name “Ukraine” denoted a relatively impoverished country with a government that inspired doubts. Now, Zelensky’s government inspires determined resistance within Ukraine, along with the admiration and support of the Western world. The nation is mobilized to support that government, and the collective destiny of the country, in a way that it had not been before. Standing right behind Ukraine is a newly reinvigorated NATO, itself transformed by the war.

Russia has undergone a somewhat different transformation. The invasion of Ukraine was truly Putin’s war — his decision, based on his mystical notions of Russian hegemony, based on his overoptimistic expectations of how successful his strategy would be. To say that he lacks the support of the Russian population that his adversary has would be an understatement. There is still a kind of social contract, based on the support of influential Russians based on continued energy-driven prosperity and widespread graft. There is still support from average Russians for Putin, but there are question marks about how honest and durable that support may be. (For example, how much does the fountain of lies erupting daily from Russian state media generate honest support? Are people responding in the affirmative out of enthusiasm, fear, or fatalism?) Sanctions and, for some Russians, the war’s offensiveness and failure have created strains that thus far have remained mostly subterranean. It’s impossible to say, under these circumstances, if that matters for the future of Putin.

It’s far less ambiguous how Russia has changed as a regional and global actor. Putin has taken Russia, in the eyes of much of the world, from being a troublemaker to a pariah and a far greater perceived threat. Even if no domestic threat emerges to Putin, his acceptability to the rest of the world has certainly changed. No amount of nuclear sabre-rattling will change that fact of international life. He has deepened his dependence on China, but lost any possibility that the rest of the world would be willing to do business with him. The questions now center around how expensive is it for countries dependent on Russian oil and gas to switch to different providers, or how many more corporations will pull their trade out of Russia. Doing business with Russia is off the table, as is any normalization with Russia in other ways. Even if there is a slim possibility of improvement, as long as Putin sits in the Kremlin, it isn’t likely to happen for a long, long time.

One thing has remained a constant: the Russian way of war, based on daily brutality. It has proven far less effective in Ukraine than in other theaters — and even in those, like Chechneya, it took a long time to have the desired result. Of course, Ukraine isn’t Chechneya: the Ukrainians have far more international support than other Russian victims had. The scale of the Ukraine war is much larger, putting more strains on the Russian military than those other conflicts. And, of course, the repercussions for Russia itself have been much greater. However, Putin and his subordinates clearly feel that they have no other choice than to continue bombing shopping malls, apartment blocks, and schools. They don’t see withdrawal as an option. Given the inadequacy of their armed forces, other operations are not feasible. And, of course, the meat cleaver approach is what they know.

If the Russians had seized Kyiv in the first weeks, if the West had been intimidated out of supporting the Ukrainians, if NATO had been weakened instead of strengthened, if the Russian military had not been hollowed out by corruption and incompetence…If, if, if. Too many wars start with optimistic assumptions that don’t pan out in reality. The predictable result is the hardening of positions, leading to a narrower set of acceptable conditions for the war’s end. And when they emerge from the conflict, the combatants will not be the same.

Good posts, great observations. But…The announcement of an agreement between the combatants for the release of Ukrainian grain exports through the Black Sea turns out to have been short lived. 🙁

The war in Ukraine is awful for the Ukrainian people, but damn it’s been freakin’ great for the US and our allies.

There’s been a narrative since Trump that the authoritarians are winning and Democracy is in retreat. Really?

China is using tanks to quell riots at banks. It’s gutting its own economy with draconian lockdowns, corruption, and xenophobic assaults on foreign companies. Its ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ is beyond stupid and self-defeating. Its belt and road initiative is likely a dead letter, and with a hollowed-out demographic with rapid aging and population decrease, they don’t look real healthy.

Russia is comically inept. They’ve destroyed the reputation of their own military, and undoubtedly done serious damage to their arms exports in the process. They’ve alienated their biggest customers. Poland is engaged in an impressive military build-up, Germany is re-arming and Sweden and Finland have joined NATO.

Meanwhile the USA that was supposed to be in decline and looking at a multipolar world in which we were perhaps at best the second ranking power, has strengthened military co-operation with Europe, Japan and South Korea and stated – much less ambiguously than previously – that we will fight for Taiwan. NATO is strong and getting stronger very quickly. The Quad (US, Australia, Japan and India) needs some work because the Indian government is behaving badly, but the assumption that Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia would inevitably succumb to Chinese influence is very questionable now.

Putin and Xi both got way too far out over their skis. They thought they were our peers and it turns out, nope, there is only one superpower.

Domestically we have some challenges with fascists, but I sense that we may have turned a corner on that. As much as progressive overreach annoys me I believe Republican overreach is even less popular and potentially disastrous for them.

On balance if this were a poker game (and it kind of is) the democracies – North America, Europe, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Australia – hold the better hand.

If Mad Vlad had invaded while his bitch Benito sat behind the Resolute desk.

@Michael Reynolds:

Another factor for China: a lot of the “Belt and Road” loans designed to leverage development oriented to Chinese products and markets, and secure assets (and graft hungry politicians) are showing signs of stress.

See Sri Lanka for the most extreme current example.

Turns out a war that sends your customers and suppliers costs of food and fuel through the roof, (and may result in a global credit squeeze as the West tackles inflation) causing potential loan defaults, was not necessarily in the best interests of Beijing.

Oopsie.

Also, that overt diplomatic alignment with a Russia that has become a direct threat to the vital interests of Europe, may in the longer term cause Europeans to think twice about supplying critical technologies, enabling investments in sensitive tech (Huawei & 5G; UK nuclear reactor projects; etc), and deep linking EU and China economies generally.

Double oopsie.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: I really wonder about the story behind the shelling. Was it part of a master bait and switch plan? Different parts of the Russian regime acting separately? Someone didn’t get the memo?

Incidentally (and this is not a poke at you Kingdaddy, just a general annoyed observation):

I get really fed up with columnists and “analysts” in a lot of “newspapers” and “broadcasters” (albeit both are now mainly web published) chuntering on about the “Russian army traditional attritional tactics” or “Russian army designed for grinding artillery warfare.”

This is just not the case.

The Soviet Army since Tukhachevsky in the 1930’s and later WW2, albeit with an interim due to it’s near collapse in Barbarossa forcing fallback to attritional defence, was of mobile operations enabled by massive artillery punching holes for exploitation.

Cold war era Soviet doctrine also was blitzkrieg-turned-up-to-11, not “grinding attrition”.

The post-Soviet approach was even more oriented to a blitzkrieg type approach due to required economy of force with the much smaller post-Soviet army.

Russia defaulted to attritional operations in Grozny, due to inability to quickly defeat urban defences.

And in Syria the close combat troops for most major operations were usually Syrian, Iranian or Hezbollah units.

Russian operations there were determined more by the choices of Qasem Soleimani than anything else.

@JohnSF:

I agree, that is some hardcore retconning going on. They’re resorting to grind-it-out warfare because it’s all they’re capable of. Combined operations are hard, that’s for highly-trained professional armies. Sitting in the rear swilling vodka while you lob shells at civilian apartment buildings is easy. I wouldn’t give a nickel for the morale of Russian troops. This isn’t making them into soldiers, they’re nothing but butchers. I suspect more than a few are watching videos of the effect they’re having and know what they are.

@Kingdaddy:

Looking like an awareness that a significant portion of Odesa would be off the target list when the grain ships arrived prompted a few Parthian shots at what appeared to the Russians to be military assets there.

@Michael Reynolds:

Also, lobbing shells, ballistic rockets and cruise missiles at Chechens or Syrians with no air-defences, counter-battery capability, PGM munitions etc is one thing.

Ukrainians who’ve been fighting Russians for years, now equipped with some the best NATO and Ukrainian weapons and tech (the Ukrainians are very smart and adaptive: some of their battle tech seems up there with NATO at the cutting edge), targeting advice etc.

That’s a whole other ballgame.

This time it’s hitting someone who can, and will, hit back hard.

I suspect sitting in the rear may become increasingly unpleasant as the summer wears on to autumn.

Already looks like Russian ammunition and fuel depots are less than healthy places to hang out.

Also, looks like Ukraine is repeatedly “tapping” the Dnipr bridges and steadily intensifying ground operations there.

Were I a Russian on the west bank of the Dnipr, I’d be seriously considering options for buggering off back to Mother Russia ASAP.

Russian problem appears to be that with inability to achieve air control, and inflexible supply and limited forces, they can only fight at high intensity for limited periods on limited sectors.

Unless they can break through, the consequence is that Russia is vulnerable to exploitation of operational and supply limitations and inflexibility.

Lobbing rockets at civilian targets is disgusting, and may have a (limited) economic impact on Ukraine.

But militarily, it’s just pissing away striking power to no avail.

V1 and V2 couldn’t break Britain (10,000 V-1s between June and August 1944, sometimes 100 a day; 1,400 V-2s. And never mind the bomber raids.)

Unlikely that Russian missile strikes almost an order of magnitude less (totals uncertain but appear to be in the low thousands) will break Ukraine.

Which is not to minimise the appalling human suffering, and the vile criminality of the acts.

@Michael Reynolds:

The war may be awful for the Ukrainian people, but they seem to think that defeat would be even worse. And the longer it grinds on, the harder it will be for Ukraine to accept a “compromise” peace.

In addition to getting Norway and Finland into NATO, Putin has forged a very independent nation out of Ukraine when before… it was fuzzy with a lot of historical connections to Russia and mixed ethnicity.

This was also probably not high on Putin’s wish list.

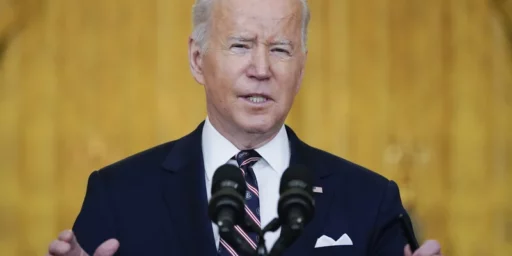

The Biden administration has been basically flawless in this war — I have some concern about Putin-lovers taking over congress, so I’m hoping this doesn’t drag out too much longer.

@Gustopher:

That’s the problem

There’s still a chin-stroking, value-my-judicious-opinion aspect to certain sections of NSC (IMHO) and German Kanzleramt and Defence ministry who still want to play grandmothers footsteps on equipment supply.

– Partly, in my nasty cynical opinion, because it inflates their sense self-importance at being at the pivotal to decision making.

– Partly due to continuing doubts about the Ukrainians being operationally sensible; which really should have set aside done with months past, given the evidence,

– Partly due to genuine escalation fears; which are misplaced, and actually counterproductive. It’s a complex topic, but worriting about it publicly invites Russian exploitation of the area of uncertainty, which in itself invites escalatory action by Russia.

– Partly some elements of German govt. and parties (both NeiderSachsen faction of SPD, and some elements in CDU; and elements of permanent civil service esp in trade and defence) still having a teenage goth sulky strop that the whole rotten Ukrainian war has smashed the sandcastles of their alles ist in Ordnung post-Cold War dream.

Realistic course is to maximise assistance to Ukraine now: because post-November the political and economic situation may turn for the worse: Congressional elections in US; winter gas in EU.