Some Context on Turkey

Turkey has had along and ongoing struggle with democratic consolidation.

Doug Mataconis’ post from earlier in the week, Turkey On The Brink?, sparked a couple of thoughts.

First, the tease to the post, “Has the Arab Spring come to Turkey?” raised immediate questions in my mind, and not just because, as commenters to the post noted, Turkey is not an Arab country. What really struck me is that my understanding of the “Arab Spring” would be the widespread popular revolt of North African and Middle Eastern populations against long-standing authoritarian regimes with pressure towards democratization (or, at least, removal or long-term dictators and some level of liberalization). While Turkey’s democratic bona fides are hardly stellar (more on the below), it does not fall into the the appropriate set of long-term authoritarian states that we see involved in the Arab Spring uprisings. I would argue that lumping in the protests in Turkey into the Arab Spring is to make a error of category at a minimum.

Second, the question of Turkey being “on the brink” raises the question of “on the brink of what?” Rather than being on the brink of liberalization of some degree (as has been the case, to date, in key Arab Spring countries like Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt*), the more likely brink that Turkey is flirting with, if Turkish history is a guide, is in the direction of more authoritarianism. It is important to know that the Turkish military has long seen its role as the protector of the Turkish state and has seen fit to take over more than once.

Third, along those lines, while it is true that Turkey has been an electoral democracy of late, it is hardly the healthiest democracy on the block, and really is on the line of between considered fully democratic when compared states that fall in that category.

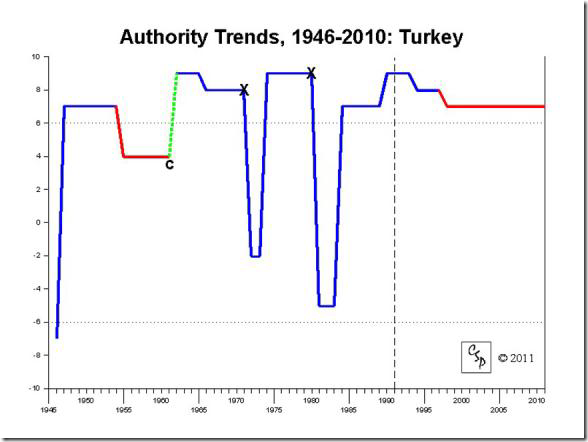

The Polity IV report illustrates this quite well. The X’s mark an “autocratic backsliding event” and the red line means a period of factionalism. A regime is considered democratic by the Polity IV measure if it codes as above the dash.

Another metric, that provided by Freedom House, classifies Turkey as an “electoral democracy” that is “Partly Free.”

The basic point is this: both Polity IV and Freedom House note the imperfect nature of Turkish democracy and should help create some level of understanding about the political context. What we are seeing is not a wholly new situation that is arising in the context of the Arab Spring, nor is it some new development endemic or new to the AKP government (although, without a doubt, the religious nature of the AKP is part of the issue).

Note that the protests in Istanbul are linked to a development project and that some of the initial motivation was linked to corruption charges, although as the BBC notes “Plans to redevelop Istanbul’s Gezi Park into a complex with new mosque and shopping centre have sparked a wave of protests in the Turkish city and beyond.”

More from that report:

critics say the decision to go ahead with the redevelopment was made too fast and without proper public and media debate.

There are also questions over the choice of Kalyon Group, a company which has close ties with the governing Justice and Development (AK) Party, as the project’s main contractor.

This is useful to understand, given that the Freedom House report notes:

Turkey struggles with corruption in government and in daily life. The AKP government has adopted some anticorruption measures, including a reform package in June 2012 that focuses on bribery and political financing. However, reports by international organizations still note only limited progress in this area. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been accused of involvement in a number of scandals related to economic cronyism and nepotism. Turkey was ranked 54 out of 176 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s 2012 Corruption Perceptions Index.

The corruption angle is an important element to this story, although not the only one, and at this point likely not the main one, as the situation has become a vehicle for expressing various frustrations (back to the BBC):

There is also a deeply political aspect. For some Turks, the proposed reconstruction of the barracks has a symbolic significance. It was at the barracks that a (failed) mutiny by Islamic-minded soldiers was initiated in 1909, in support of the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and intent on bringing in Sharia law.

The barracks were demolished in 1940, and attempts to rebuild them are seen by opponents to have the ring of Islamism and neo-Ottomanism.

This protest has now become about more than just Gezi Park.

It has broadened into a wider expression of anger at what protesters see as the government’s increasing authoritarianism – and also the heavy-handed tactics of police who used tear gas and water cannon to disperse a peaceful rally, resulting in scores of injuries.

Taksim Square has seen several other demonstrations this year, including one on May Day in which police also fired tear gas at protesters.

Another issue is the renaming of one of the Bosphorus bridges after Sultan Selim II, a pre-Ataturk Ottoman leader.

Police overreaction to the original protests have certainly fueled the protests.

There is clearly a great deal of tension in Turkey between its secularist constitution and history and its religious population, including the AKP government.

At any rate: there are some superficial similarities here to Egypt (a key square being the focal point, for example) and the general fact that street protests were associated with the Arab Spring, but I think that the broader political context suggest that we need to understand these events as being something other than just “the Arab Spring comes to Turkey.”

Along the Arab Spring comparisons, I would agree with the following from a BBC Q&A on the subject:

Turkey is not comparable to those Arab countries which had never known democracy. Firstly, the government owes its legitimacy to three successive election victories. The AKP won the last polls, in 2011, convincingly with international monitors generally satisfied that they had been conducted fairly. Secondly, Mr Erdogan and his party appear to still enjoy a bedrock of support in the wider country. A Pew opinion poll taken before the protests suggested that 62% of Turks took a favourable view of him, though it found this support falling sharply in the Istanbul metropolis, and among secular Turks in particular. Thirdly, under the AKP, Turkey has enjoyed economic growth as well as growing prestige as a regional power.

Such information runs counter to the Arab Spring narrative, since those movements were about ousting leaders and changing regime types.

For another summary, see theAP/WaPo: Turkey protests unite disparate groups chafing at prime minister’s policies.

*This is not to say that any of these cases have made a successful transition to democracy or that they are necessarily likely to do so. However, all of these cases have move in the direction of liberalization away from clear authoritarian rule. I will not attempt here to get into an evaluation of each case. Beyond the complexities of such assessments, the bottom line remains that the cases are all in process and have hardly settled on a final new regime type.

I know Turkey isn’t an Arab country, but then neither are Libya and Tunisia, which are predominantly Berber, a distinct ethnic group different from Arab. However, “Arab Spring” is the term that has generally been applied to the popular movements that swept across the region, from Baharain to Morocco, in 2011.

@Doug Mataconis: All well and good, but really that isn’t my main point at all. I think it is really important to understand the regime types in question and the direction and nature of possible change.

Mostly agreed, Steven. I would add that Turkey has had a secularist constitution for a century which some of its urban poor and rural people, more religious than urban secularists, chafe at. The tension isn’t just between secularism and religion but among social classes, urban and rural, and ethnic tensions as well.

@Dave Schuler:

As is the case in just about any country.

But, since Turkey borders the Mid East, as is a predominantly Muslim country, it’s always going to be either (a) about religion or (b) about how they hate the West.

Great article Steven.

@Doug Mataconis:

It´s not a matter of ethnic group, but of language. Al Jazeera Arabic was one of the main factors in all these revolts.

Deustche Welle did an excellent report about the subject:

http://www.dw.de/european-journal-the-magazine-from-brussels-2013-06-05/e-16815644-9798

The video talks about a sculptor, and how Erdogan managed to destroy a big sculpture that he was building. There is also other issues, linked to the development of Istanbul, like people losing their homes for big development projects.

There is a very popular Turkish soap about an Ottoman Sultan. The story is centered around the sexual tensions and intrigues in the palace, not the military conquests.

Obviously, Erdogan and people in the AKP found time to condemn the soap opera. An MP even wanted to ban the representation of historical figures on TV.

There’s an additional corruption angle: Erdogan’s son-in-law holds the contract for construction of the mall.

Great article, Steven. You always do a job of presenting complex topics in an understandable way using clear language.

Also too, part of the reason for the uprising is domestic opposition to the Turkish government’s stance on Syria:

The longer the Syrian civil war goes on, the more pressure there will be on the Turkish government to stop supporting the rebels. The Kurds are getting restless too.

Der Spiegel has an interesting article on this topic.

http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/revolt-in-turkey-erdogan-losing-grip-on-power-a-903553.html

@Dave Schuler:

Indeed.

@Matt Bernius and @Gromitt Gunn:

Thanks–kind of you both to say.

@ Doug

Well, Libya and Tunisia do belong to the Arab League. Perhaps you should let them decide what they are.

@Doug Mataconis: Upon further reflection and checking, Libya and Tunisia are both Arab countries, as is Morocco and Bahrain (Arabic is an official language in both).

Indeed, I am pretty sure that every country that has been thus far tagged as part of the “Arab Spring” has Arabic as an official language (either as the sole language or as one of a menu).

But again, that really isn’t my point. My point is that in a session of that old Sesame Street game “one of these things is not like the other,” Turkey is decidedly not like the Arab Spring cases in terms of the political, historical, and institutional parameters under which the current crisis is taking place.