American Public Prefers A Less Interventionist U.S. Foreign Policy

A new poll finds the American public far less supportive of the idea of the U.S. as the world's policeman.

A new poll conducted by the Pew Research Center on behalf of the Council on Foreign Relations indicates that the American public has become more skeptical about the idea of the United States as the world’s necessary global actor and, most significantly, on the whole issue of U.S. intervention in conflicts around the world than it has been in the past half-century:

Growing numbers of Americans believe that U.S. global power and prestige are in decline. And support for U.S. global engagement, already near a historic low, has fallen further. The public thinks that the nation does too much to solve world problems, and increasing percentages want the U.S. to “mind its own business internationally” and pay more attention to problems here at home.

Yet this reticence is not an expression of across-the-board isolationism. Even as doubts grow about the United States’ geopolitical role, most Americans say the benefits from U.S. participation in the global economy outweigh the risks. And support for closer trade and business ties with other nations stands at its highest point in more than a decade.

(….)

The survey of the general public, conducted Oct. 30-Nov. 6 among 2,003 adults, finds that views of U.S. global importance and power have passed a key milestone. For the first time in surveys dating back nearly 40 years, a majority (53%) says the United States plays a less important and powerful role as a world leader than it did a decade ago. The share saying the U.S. is less powerful has increased 12 points since 2009 and has more than doubled – from just 20% – since 2004.

An even larger majority says the U.S. is losing respect internationally. Fully 70% say the United States is less respected than in the past, which nearly matches the level reached late in former President George W. Bush’s second term (71% in May 2008). Early last year, fewer Americans (56%) thought that the U.S. had become less respected globally.

Foreigthn policy, once a relative strength for President Obama, has become a target of substantial criticism. By a 56% to 34% margin more disapprove than approve of his handling of foreign policy. The public also disapproves of his handling of Syria, Iran, China and Afghanistan by wide margins. On terrorism, however, more approve than disapprove of Obama’s job performance (by 51% to 44%).

The public’s skepticism about U.S. international engagement – evident in America’s Place in the World surveys four and eight years ago – has increased. Currently, 52% say the United States “should mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own.” Just 38% disagree with the statement. This is the most lopsided balance in favor of the U.S. “minding its own business” in the nearly 50-year history of the measure.

After the recent near-miss with U.S. military action against Syria, the NATO mission in Libya and lengthy wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, about half of Americans (51%) say the United States does too much in helping solve world problems, while just 17% say it does too little and 28% think it does the right amount. When those who say the U.S. does “too much” internationally are asked to describe in their own words why they feel this way, nearly half (47%) say problems at home, including the economy, should get more attention.

However, it’s important to note that this disdain for international engagement on a military and diplomatic interventionist level does not extend to all forms international engagement, especially on the economic level:

But the public expresses no such reluctance about U.S. involvement in the global economy. Fully 77% say that growing trade and business ties between the United States and other countries are either very good (23%) or somewhat good (54%) for the U.S. Just 18% have a negative view. Support for increased trade and business connections has increased 24 points since 2008, during the economic recession.

By more than two-to-one, Americans see more benefits than risks from greater involvement in the global economy. Two-thirds (66%) say greater involvement in the global economy is a good thing because it opens up new markets and opportunities for growth. Just 25% say that it is bad for the country because it exposes the U.S. to risk and uncertainty. Large majorities across education and income categories – as well as most Republicans, Democrats and independents – have positive views of increased U.S. involvement in the world economy.

In other words, has grown weary of what has seemed like and endless cycle of military intervention that has marked virtually the entire first thirteen years of the 21st Cenury. This is no doubt motivated by the experience of the Iraq War and a military commitment in Afghanistan that, pending the outstanding negotiations over a Status of Forces Agreement with Afghan President Hamid Karzai, who is still refusing to sign on to an agreement that the Afghan Parliament has already endorsed until certain issues of concern to him are endorsed, could last until 2024 or later. In addition to those factors, there’s also the specter of an intervention in Libya that, in hindsight, is proving to be far less of a rosy scenario than it initially appeared to be when the civil war there ended in August 2011 and a near intervention in Syria that, until being rescued by a deal regarding that nation’s chemical weapons program brokered by Russia, was widely opposed by the public at large. Recent polling has also indicated that the public is largely supportive of the idea of negotiating with Iran as a means to deal with its nuclear research program rather than engaging in further military confrontation. The public, it seems, is tired of war and tired of the United States must involve itself in every potential conflict around the globe.

At the same time, though, it would be unfair to label the public’s attitude as “isolationist” when, at the same time, they are strongly in favor of the nation’s role in the global economy and in favor of seeing that type of international engagement expanded in the future. Arguably, in order to qualify as true “isolationism” we’d also expect to see the public dismissive of the importance of engagement in the global economy in general and the broadening of international trade specifically. This was a common attitude in the 1930s, for example, when what is now generally derided as “isolationism” was a strong force in American politics. To be fair, public attitudes on international trade and related issues do tend to fluctuate with the state of the economy. When the domestic economy is strong, you’ll generally find that the public is supportive of the idea of bilateral international trade. When the economy weakens, however, it isn’t uncommon to see international trade and the idea of foreigners “stealing our jobs” gain currency among people who have been impacted by the bad economy regardless of how fallacious the idea that international trade hurts the domestic economy might actually be.

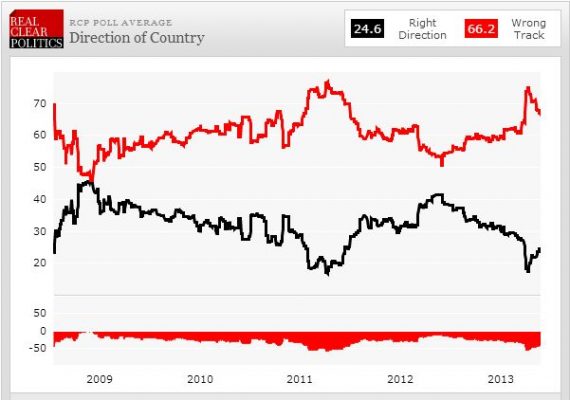

Perhaps the most interesting takeaway from the poll, though, is found in the fact that increasing numbers of the American public sees the U.S. as playing a lesser role in the role in the world today than it has in the past, and that it has lost respect in the world over the years, and they seem entirely okay with that. Does this mean that the jingoistic vision that once motivated American foreign policy in both parties, and which seems to still be a strong part of foreign policy in the Republican Party is fading away? Or, is it a reflection of a general pessimism about the direction the nation has been moving in the past decade or so? You can see that pessimism in the benchmark right track/wrong track poll, which has been harshly negative for the vast majority of the Obama Administration, this chart from RealClearPolitics shows:

With numbers like that, it’s not surprising that Americans would see their nation as less influential in the world. What’s interesting, though, is that their responses to the underlying questions about future U.S. intervention around the globe, they seem perfectly fine with letting it stay that way.

– After 20 years we may finally be getting used to the idea the Cold War ended.

– After 12 years we may be returning to some level of normalcy after 9-11.

– Afghanistan and Iraq are generally recognized as decade long, hugely expensive failures.

So there seems to be a recognition that we don’t need to intervene, and that we aren’t very good at intervention; so why would we want to do more of it?

While I truly hope that we actually prefer a less interventionist foreign policy, I suspect that that sentiment is three miles wide and a half-inch deep.

All too often the case is made that our nation is threatened by the existence of a despot or a particular regime – Saddam Hussein, Moammar Qadaffi, Iran, North Korea, or whomever – and based on the most slender evidence the people get in line behind the president as he takes action.

The American Public WANTS to be isolationist, but is generally prepared to support interventions. Right now we’re at a high level of interventionist fatigue, understandable give our 10 year intervention in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

The paleo-cons are going to get what they want but not for the reaon the want it. I think the real reason people want international adventures to end is because every dollar spent on war, foreign aid, or paying off allies is a dollar not spent on them.

I also suspect that the growing percentage of the population that are immigrants and first generation Americans means that they are interested in the economy but not military or diplomatic power.

I think that what al-Ameda, above, points out has merit but I think there’s another explanation. Only interventionist candidates can get funding from major contributors. That means that by the time the people have a chance to have their say they have their choice of interventionist candidates.

@Dave Schuler: Indeed, the military industrial complex votes with their checkbooks.

The pendulum of American militarism swings on a long timescale, over many decades. It swings back now, and none too soon. I could have done without Iraq II, or more than a quick punishment of Afghanistan for shielding Bin Laden.

Occupation and nation building were militarist fantasies. I hope they are gone again for another 40 years.

Does this mean Duncan Hunter can’t nuke Iran?