Basic Democratic Models

Presidential v. parliamentary democracy, some basics.

The basic notion of representative democracy in its various forms is that the popular will of the citizenry is translated into government that serves for a time and attempts to govern in a way that comports with the will of the voters who elected it. There are various ways to construct such a system, with the two major types being presidentialism and parliamentarism.*

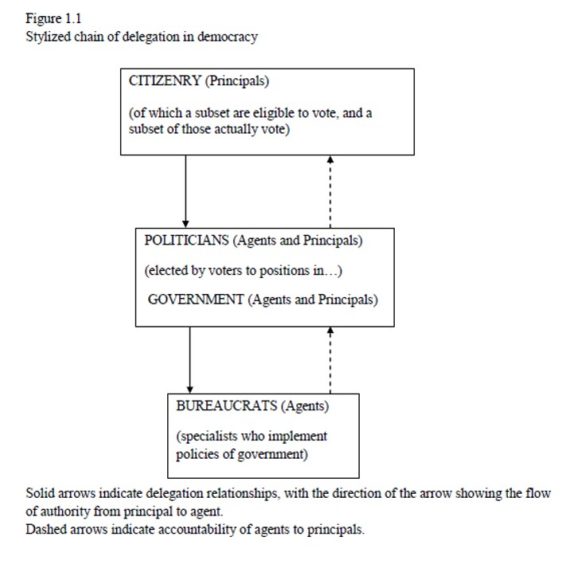

A basic model of democracy, as I have shared before, looks like this:**

The key issue here is that the power to govern comes from voters. But, of course, the simplified model is not what tends to exist in reality, although it is pretty close to what a unicameral parliamentary system would look like. That is: the voters choose the parliament and parliament chooses the government (PM and cabinet).

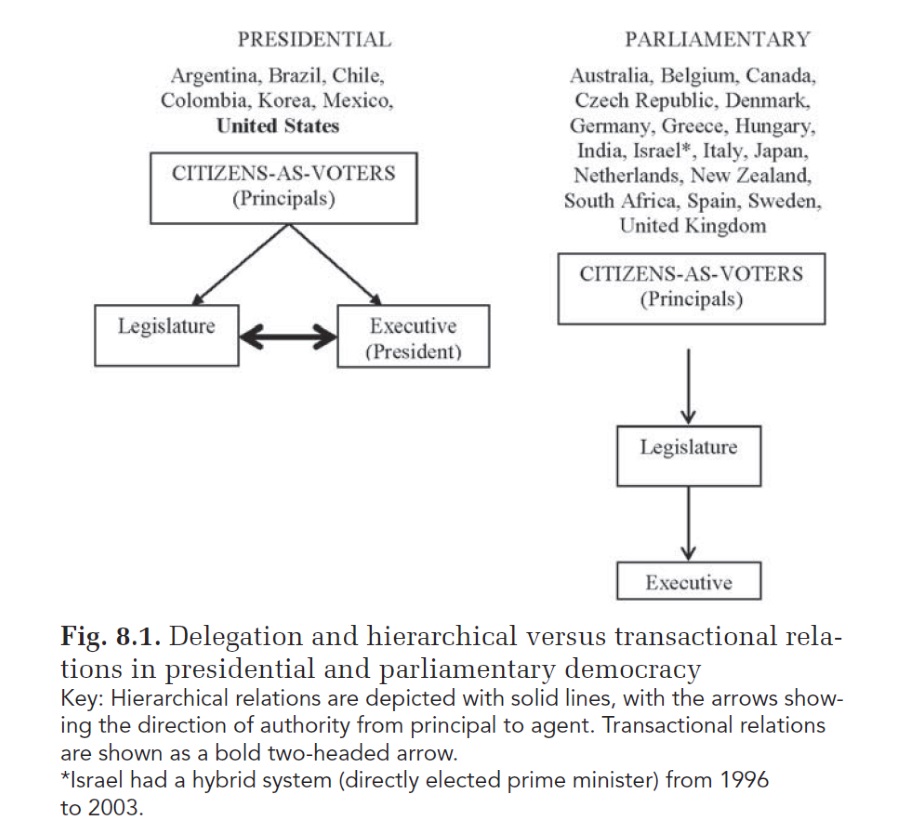

In parliamentary systems the voters delegate to the legislature only. In presidential systems they delegate to the president and to the legislature.

Of course, either model can be further complicated if there is an elected second chamber and/or if there is are elected sub-unit (e.g., state) level.

Of the various implications of the dividing of governmental power into discrete elected units is the question of who is really responsible for both successes and failures of governing in a given period of time. In parliamentary systems the issue of responsibility is clearer, given that the majority party (or coalition of parties) is clearly the course of both legislative and executive decisions.

Note that in the parliamentary model, the power to select the government (the PM and cabinet) is given to the parliament by the voters. (This is the basis of my previous post on the UK situation). And, ultimately, parliamentary democracy focuses more on parties than on persons (although, certainly, individual leaders are important and can very much matter politically and electorally).

But, as with the Boris Johnson issue, the voters in a parliamentary system empower parties to govern, not individuals. The parties choose individuals (the Prime Minister, but also the other Ministers of government) to exercise that power.

One can argue the virtues or vices of separate elections for executive and legislature, but it should be quite clear that the democratic accountability exists in both systems, and I would argue is actually more acute in the parliamentary system given that the voters know full well whom to blame or give credit to.

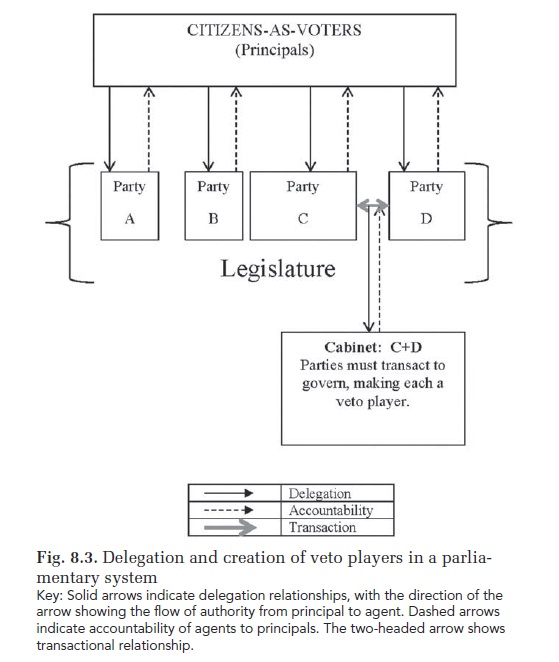

To further map these ideas out, here is a model for a parliamentary system with multiple parties:

Note that the voter vote for parties and then the parties that are able to work together to control a majority of seats are given the responsibility of forming the government. Again: a parliamentary system empowers parties to govern, not specific people.

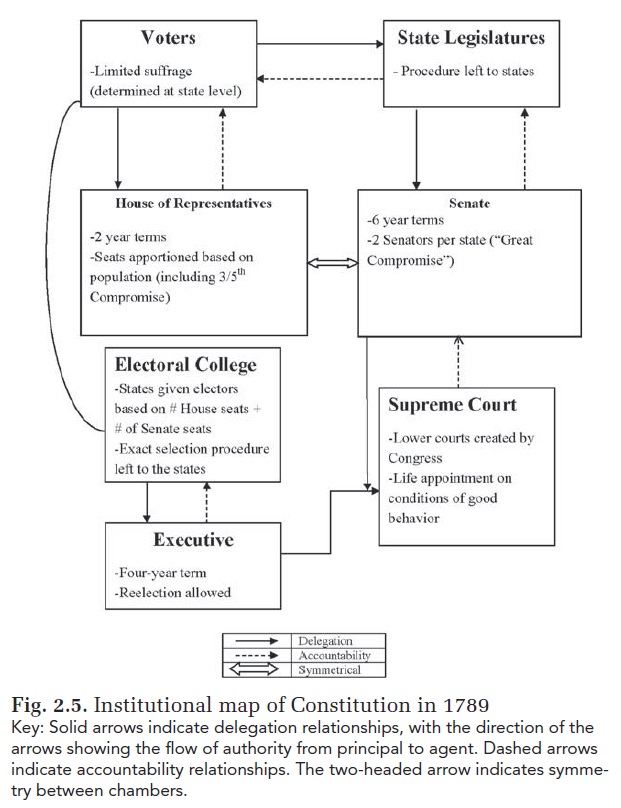

And here is a model of the US system under the 1789 constitution before popular election of Senators:***

This is a more complicated model that split citizen input into multiple pieces. On the one hand, citizens are able to have an input on the House, Senate, and Electoral College,**** but that also means that each component can blame the other/take credit.

*There are other various including semi-presidential systems like France which have both an elected president and prime minister. There are also variations linked to how many chambers in the legislature (and what powers those chambers have), federalism, and a host of others. See Taylor, Steven L., Matthew S. Shugart, Arend Lijphart, and Bernard Grofman. 2014. A Different Democracy: American Government in a 31-Country Perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press.

**Fig 1.1 from Taylor, et al., 10; Fig 2.5, 56; Fig 8.2, 232; Fig 8.3, 240

***I need to make one that reflects the changes the system has undertaken, but not today.

***The electors were chosen by a variety of methods early on, with the popular vote becoming the norm around the middle of the 19th Century.

Pretty sure it was in Samuel Levinson’s Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong (And How We the People Can Correct It) that the author brought up data showing that parliamentary systems tend to bring out cooperative approaches to governance as it’s difficult for a single party to make headway without teaming up with other factions. While two-party systems, in which politics is a zero-sum game, lead to competition and a variety of dysfunctional traits such as gridlock. Though that was a pretty compelling point against a two-party system.

I suppose it’s unfair to quibble with a post that tries to cover issues many whole books have been written about. However there’s a fundamental contradiction between “The basic notion of representative democracy in its various forms is that the popular will of the citizenry is translated into government that serves for a time and attempts to govern in a way that comports with the will of the voters who elected it” and much of what follows.

In the Westminister system, the popular will of the citizenry is translated into a parliament that serves for a time and attempts to govern in a way that comports with the will of the voters who elected it. The parliament decides who will be the government by expressing its confidence in a prime minister. The person who commands the confidence of the parliament will be the prime minister as long as s/he maintains that confidence. For example, unlikely though it may be, Jeremy Corbyn could become prime minister of Great Britain simply by having a majority of the House of Commons express no confidence in Theresa May and voting confidence in Corbyn. While this would come as a shock to many voters, it would not be a breach of the Westminister system. The parliament they had elected would have appointed the government.

Of course the usual course of events is that the House would vote no confidence in May (or Johnson when he succeeds her), but also decline to vote confidence in anybody else. This leads to a new election being called, which will hopefully result in someone having a clear majority. But sometimes that doesn’t happen, as in Israel right now, meaning no government can be formed for an indefinite period because nobody can command the confidence of a majority of parliamentarians.

Parliamentary systems can potentially become dysfunctional just as other forms of representative government can. At least calling for fresh elections provides a mechanism that gives the people the authority to resolve the gridlock. Other constitutions allow the head of state to rule by decree when parliament cannot form an effective government – the provision that was the downfall of the Weimar Republic.

A glaring weakness of the US constitution is the absence of any mechanism to break gridlock in Congress. Indeed if I read the constitution correctly, the House could convene in January for a day and vote to adjourn indefinitely, leaving the nation to collapse into chaos. The president in that scenario would be under enormous pressure to rule by emergency declarations (even assuming s/he wasn’t predisposed to do that anyway), and it’s difficult to see how anyone could do anything about it.

One problem with all models of democracy, and we can include the ancient models of Athens and Rome as well, is that they are largely idealized. They work reasonably well while the players adhere to the ideals. They stop working well, or at all, when people figure out a way to game the system.

There’s a Trek novel called “Spock’s World,” very much worth reading BTW, dealing with a Vulcan plebiscite on seceding from the Federation (with interspersed chapters of Vulcan history). Out intrepid heroes have to argue in public fora for the Federation (seriously, that’s what it’s about).

Spock at one point describes the Vulcan government. Among the details, there is a legislative chamber in charge only of repealing laws. That is, they vote to keep or repeal a law. the way it’s explained, it takes a minority vote, say one third, to repeal. The rationale is that bad laws should be easy to remove, as they cause more harm than good.

Not a bad notion, in the abstract, but try to imagine something like that in modern democracies. Gaming that would be child’s play.

Or consider the filibuster. In theory it provides protection from a bare majority which may not be representative or sustained, from imposing its will on a whole nation. In actual fact, it allows minority parties to obstruct the majority, no matter how vast.

In the case of the US, part of the ideal is that the various government powers will want to exert their influence and assert their prerogatives. This never worked quite that way, but while parties were diverse it worked well enough. Now with largely monolithic parties, it hardly works at all.

@Kathy: Yes, norms matter.

I would add that the point of an exercise such as this is to illustrate how rules are supposed to channel power and decisions–it is not to suggest that they always work perfectly (or even well). Ideal types serve a real purpose.

I read it well over 30 years ago–and cannot remember one whit of, save that I thought it was pretty good. I think I have the paperback still.

The Virginia Plan had an institution like that called the Council of Revision.

@Ken_L:

Sure-if Labour could form a coalition (or, at least, get a formal agreement with) other parties. It would require majority support in the Commons. That fits my initial point.

Indeed.

There are a lot of reasons the Weimar Republic collapsed, and it was not just because of one provision in the constitution. Using Weimer as a cautionary tale about the fragility of parliamentary systems is problematic at best, and really more not relevant. Weimar was facing not only a massive economic crisis, but many of the parties vying for power were anti-regime (i.e., they wanted to tear down the system–monarchist, communists, and Nazis to name three).

Weimar (along with Italy and Israel of late) are used, often, as cautionary tales of parliamentarism, but even if they are (and I question the degree to which any of them are) ignores the degree to which there are lots of counter-examples of parliamentarism that do not have the maladies those systems allegedly prove.

Speaking of Israel,

Israel’s electoral system is, arguably, too proportional and hence the complexity of building coalitions. Although, on balance, things work fine. I can think of worse outcomes than governmental gridlock having to result in another consultation of citizens. (As you note).

BTW, I honestly do not see where “a fundamental contradiction” exists in this post.

@Steven L. Taylor: In my experience Israel always seems to come up in discussions of the supposed problems with proportional representation. But most other countries with PR have a higher threshold than Israel’s (3.25% currently, 1% originally), and the country has unique sectarian elements that make it hard to generalize about how it would function elsewhere.

@Steven L. Taylor:

It seems more like a combination of prior judicial review and presidential veto.

I’ve often thought that judges, legal scholars, or both, ought to review laws and ballot propositions for Constitutional issues, in an advisory capacity. That would save the courts a lot of time.

I read “Spock’s World” sometime in the 90s, likely shortly after it came out. Some Trek novels are pretty good.

@Kylopod: The issue with PR is Israel is district magnitude (M).

Simply put, the entire Knesset is elected from one district with a magnitude of 120 seats. Combine one big district and highly proportional electoral formula for turning votes into seats and you get a lot of small parties, especially in a plural society.

District magnitude is a huge variable. A highly proportional system with low magnitude districts will produce less parties than a system with large average M.

A simple illustration is the Colombian congress. The Chamber and Senate use the same electoral formula (closed list PR using the D’Hondt method) but the Chamber uses moderately sized districts and the Senate one big M of 100. Smaller parties do better in the Senate than in the Chamber.

@Kathy:

It was–I was just commenting that it was “like” what you were describing.

I read a ton of Trek novels in the 1980s and 90s (and a smattering after that). I have to admit, most of them didn’t stick with me. The best were written by Diane Duane (didn’t she write “Spock’s World?”) and Peter David.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I agree, though Peter David has some bad literally habits. Duane also wrote “Dark Mirror,” a reasonable yarn set in the Mirror Universe in Next Generation times.

In “The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress” (written in the 60’s maybe?) Robert Heinlein brainstormed several forms of government, including one with a chamber that needed a 2/3rd vote to pass laws, and a second chamber that could repeal any law with a 1/3rd vote. It sounded appealing when I was younger, but watching gridlock paralyze us the last couple decades I think I’ve changed my mind.