On the Number of Parties 1: Basic Counting, Part 1

Counting is not necessarily as straightforward as it may seem.

So, a back-and-forth in the comment section (plus some other observations made by participants) in one of James Joyner’s posts inspires me to write about some things that I thought about writing about for a while now: counting parties. This series of posts (at least four, and maybe more) will look at the following topics: two on basic counting, one on complex counting, and at least one on Duverger’s Law. This is all stuff I have written about in one way or the other over time, but never quite this directly here at the site.

Let’s just start with the broad category of how we generally talk about party systems. We speak, for example, about one-party, two-party, and multi-party systems. On one level, that seems all you need to know: after all, it sounds like how many parties operate in the system (but this is, not surprisingly, a bit of an oversimplification). Clearly, a system that truly has only one party is authoritarian because it bans other parties from existing or, if they are allowed to exist, they are not allowed to govern. Still, it is worth noting that there have been examples of one-party dominant systems: countries where one party consistently wins free and fair elections For example, Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party was totally dominant from the mid-1950s until the early 1990s. Another example would be the African National Congress, which has been the dominant post-Apartheid party in South Africa (it has had a majority of seats in the national legislature for decades).

A two-party system has, well, two parties (more or less). The “more” part is that when we talk about two-party systems it is because there are only two parties that are sufficiently competitive that they win seats in any way that is consequential (even if more than two parties exist). By “consequential” I mean big enough to win a majority of seats on its own without the help of a coalition partner.* In the US we know, for example, that either the Democrats or the Republicans will win control of the House and Senate (although at the moment two independents are needed for the Dems to have 50 seats in the Senate, for whatever that is worth). The fact that we in the US colloquially refer to all the other parties as “third” parties is a bit of a tell as to the significance of those parties. Yes, other parties can exist and win office in a two-party system, but they tend not to matter much, and when they do it is a rather big and unusual deal.

Multi-party systems have three or more consequential parties (which is a wide range, I would note–are three parties important? Five? More?). But “how many?” and “how consequential?” are questions of significance. A system can have multiple parties (as does Japan) and still have a singular party that is pretty dominant. Germany has a multi-party system but really only two have historically had the chance to form the government. Israel, on the more multi-side of the spectrum, has a substantial number of parties, with new parties emerging with some frequency and small parties having a lot of influence.

These are broad categories that obscure a lot of detail. The rest of this post is looking at two examples (just because of length): the US and the UK. The next post will look at Germany and Israel. Note that in all cases all focus on legislative elections and if the case is bicameral, on its first chamber (which is good because both the UK and Germany have appointed second chambers!).

I have chosen the US for obvious reasons: it is our central focus here at OTB. I chose the UK as while it is a parliamentary system (i.e. the executive is elected out of the legislature), it elects the House of Commons in single-seat plurality elections, just like the United States (but it does not use primaries–an extremely significant difference). Its parliament (a word that is synonymous with “legislature,” by the way) is oversized for its population, while the US’ is undersized (IIRC, experts would suggest that if the countries swapped sizes, each would be just about right, give or take).

One side note about parliamentary systems: there is often an error I see Americans make using this term, which is to assume that parliamentary systems are automatically multi-party or that parliamentary means proportional representation. Neither of these things is the case. Again: a “parliamentary” system is one in which the executive (the government, i.e., the PM and cabinet) are chosen by the legislature from within the legisature. In such system the government must have the confidence of a majortity of parliament to persist. In presidential systems, the executive is elected separately and does not need the confidence of the legislature to remain in office. (There are also semi-presidential systems, like in France, that have elements of both–this post is already too long, so I will leave that aside as it is not central to the topic of counting parties).

I would note one other terminological issue: when counting parties there are two categories: parliamentary parties (parties that win seats) and electoral parties (parties that compete for and win votes). A party can exist and compete in elections and never win office.

The United States

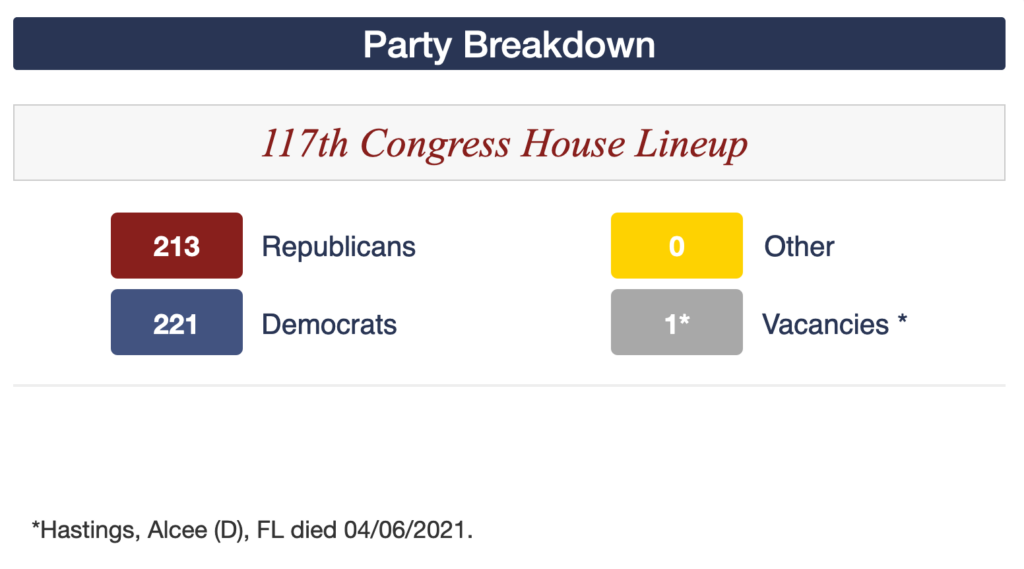

In truth, the US is pretty straight-forward (certainly moreso than most cases–and if the US is the only case with which one has familiarity, it can skew one’s overall understanding of these concepts). If we look, for example, at the current seat distribution in the US House of Representatives, we find the following:

Now, this isn’t complicated: there are all of two parties with seats. In just pure, raw couting, we have two parliamentary parties. Further, their seat shares are awfully similar. This is almost as pure a manifestation of bipartism as one is going to find: 48.97% for the Rs and 50.80% for the Ds.

If one is interested, one can peruse the historical seat distributions here. One will find a handful of independents, although there hasn’t been one in the House for almost a decade and a half. To get the non-R+D numbers to be in the double digits, one has to go back to the 1930s.

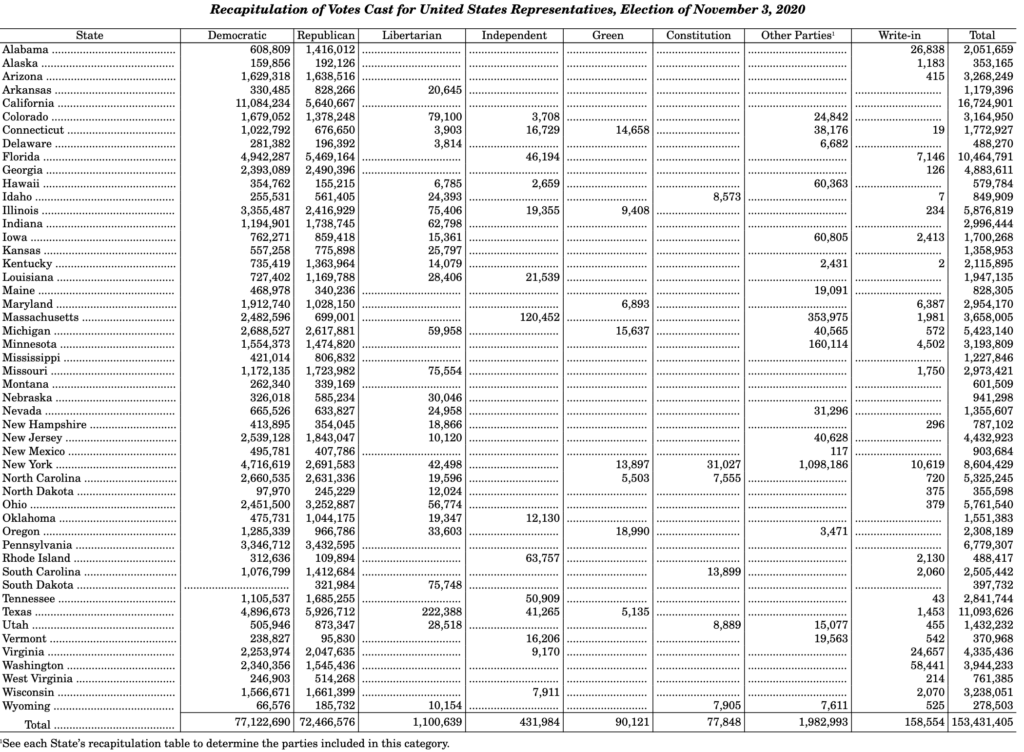

But, what about electoral parties? That is: how many parties competed for votes?

Well, that answer is at least 28 (based on my quick count of unique party labels and ignoring write-in candidates in House elections across the 50 states in the 2020 elections). If I counted presidential parties, it would probably be more.

Here are the basics:

Basically, just shy of two dozen (and again, it was a quick manual count, so I may have missed one or two) account for the almost 2 million votes in the “Other Parties” column.

Two million sounds like a lot, but not when you consider the winning parties won over 70 million and when we consider that the two million is spread over two dozen parties.

Basically:

| Votes | Vote Share | |

| Democratic | 77,122,690 | 50.27% |

| Republican | 72,466,576 | 47.23% |

| Libertarian | 1,100,639 | 0.72% |

| Independent | 431,984 | 0.28% |

| Green | 90,121 | 0.06% |

| Constitution | 77,848 | 0.05% |

| Other | 1,982,993 | 1.29% |

| Write-ins | 158,554 | 0.10% |

| 153,431,405 |

Being somewhat simplistic, I am counting Independents, Other (23 unique party labels), and Write-Ins like they are individual parties.

Clearly, it would be silly to call this a 28 party system. Just the eyeball test suggests it is a two-party system. Put another way, 97.50% of the voter share went to the two mainline parties Roughly 26 parties split the remaining 2.50%, with the LIbertarians getting the largest share at 0.72%.

Now, one can ask (and I will come back to this in a subsequent post): why do these parties fare so poorly? All well and good, but even doing a raw count to include seats and vote shares, this looks like a two-party system to me (and, well, to political scientists in general).

The United Kingdom

How about the UK’s House of Commons? It makes for an interesting comparison because of a variety of factors. There are shared linguistic and cultural characteristics with the US. Plus, as noted, it elects its legislature using essentially the same electoral system (but, importantly, without primaries). Further, it has two dominant parties, the Conservatives and Labour. Indeed, many US textbooks may have described the system as mostly two-party (I recall books some decades ago calling it a “two-plus” or “two-and-a-half” party system because it has not had the same strictness to its system as has the US.

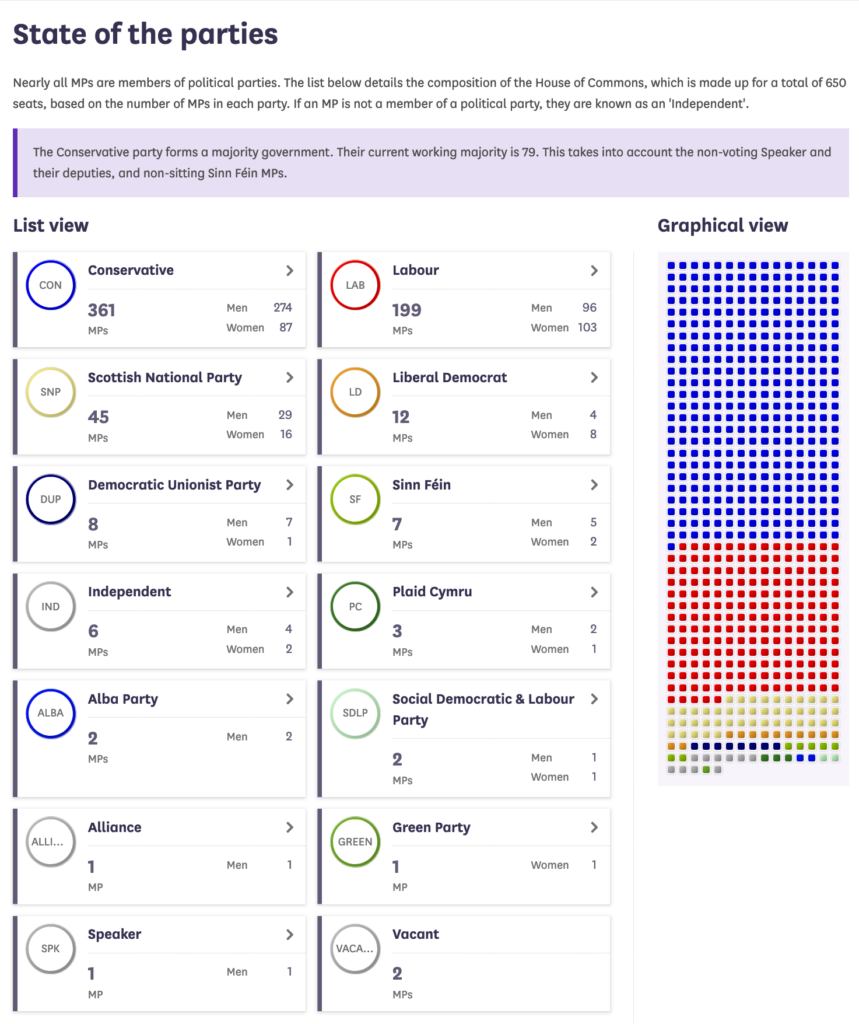

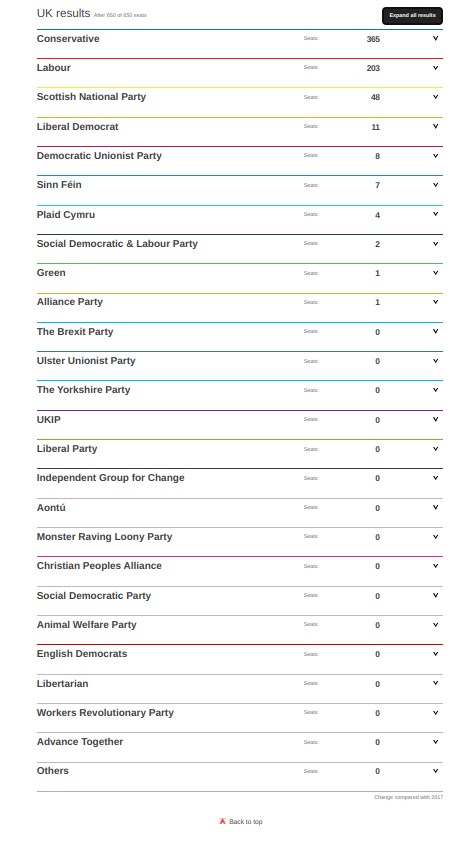

Here is the current seat distribution by party of the Commons:

On a raw counter, there are 11 parties (plus independents). So, on one level, a multi-party system, although when we look at the numbers, that still doesn’t quite seem accurate. After all, there are two large parties: the Conservatives with 361 and Labour with 199 and then a pretty big drop-off to the SNP at 45 and the Liberal Democrats at 12. From there it is single digits all the way down, several with the singlest of digits.

Clearly, only the Conservatives and Labour have any shot at forming a government (and Labour would likely need help as the Conservatives did not that long ago when they formed a coalition with Liberal Democrats).

What about electoral parties? There are even more of those (at least 25–I am not sure how many “other” entails):

To look at that list in detail, see here.

Later I am going to return to the question of why the UK has several viable parliamentary parties and the US does not. I will also return to the question of how to count these parties in a more complex, comparable, and useful way.

Next up: a look at more truly multi-party systems.

*Update: Upon re-reading, I realize I would refine my definition of “consequential” to some degree were I writing a second draft of this. A party can be consequential if it has the power to be a coalition partner to help another party form a government or has enough seats that it can block legislation from moving forward (and in parliamentary systems, those things are often linked). The bottom line is that in a system we call two-party, there are only two parties that really matter in terms of controlling the legislature and the executive. Colombia prior to 1991 was a two-party system, if one wants another, very different, example. If memory serves, Barbados has a stable two-party system, as do some other Caribbean countries.

Thank you. I’m looking forward to reading everyone’s thoughts on this; it’s going to take me a bit of pondering…

“

Asian DawnAontu?”“I read about them in Time magazine.”

Steven, I hope you also address what material difference each system makes for the country involved, other than more or fewer parties obtain office.

There is a phenomenon that seems worth a footnote on the two-party system. In some situations a ‘third party’ will act as a control on a major party by staking out a piece of the ideological terrain. In NYC once upon a time there was a Conservative Party and a Liberal Party. They had the option of endorsing the R-party candidate (if Conservative) or running a candidate against him. And of course the Liberals did the same.

I thought of this with the Shropshire election in GB recently. Why a minority party? Did the Lib-Dems act as a ‘stalking horse’ for the Laborites? Is this a universal sort of event?

FWIW, Mexico seems to have settled on three parties, plus a few extras.

The Chamber of Deputies, equivalent to the House of Representatives, is made up of first past the post districts, plus some “relative majority” deputies I’m not sure how they are apportioned. There are no runoffs or ranked choice, and whoever gets the most votes wins, even if it’s a minority of the votes (and this goes for all elections).

Parties can form alliances or coalitions before an election, and not necessarily for every election. Say parties 1 and 2 present the same candidate for president, but run their own candidates for Deputies and Senators.

The major parties are:

PAN (National Action Party), which is right of center.

MORENA (National regeneration Movement; hey, I just translate the names), nominally left of center, but really His Majesty’s Manuel Andres the Zero’s personal party.

PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), which goes for whatever will get them to win elections, be it left, right, center, etc. Between the end of the Revolution/civil war in 1921 and 1988, they won all elections at all levels, and tolerated other parties so long as they didn’t win or cause trouble. Back then, the party’s ideology was best summed up as “whatever keeps the PRI in power.”

The one notable minor party is the PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution), which was in the top three as the left of center party, until His Majesty took his ball and set up a new party. Since then it has improved in the quality of governance, but has lost popularity.

Overall there is less partisanship than in the US, much to His Majesty’s chagrin. Existing rules also tend toward fostering compromise between parties, even when one has a majority in the Chamber.

@JohnMcC: When I voted in NY, I always assumed the Conservative and Liberal parties were just an extortion racket. Some years they ran their own candidate but almost always they would cross endorse the Republican or Democratic candidate, respectively. And then get funds to promote that candidate on their own line. I never, ever heard of either of those parties doing anything other than cross endorse candidates. They never rallied or organized or tried to back causes or anything else.

@MarkedMan: I will not contest the idea that the Liberal/Conservative parties in NYC are ‘extorting’ the major parties. Not the word I’d use but perfectly descriptive.

It’s noteworthy, too, that there are a whole lot more UK parties that can win seats now than there were when Steven and I were in grad school. In those days, it was just the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberals. The settlements with the IRA and Scottland over the years have given the rise to territory-specific parties that are represented in the national parliament but have no hope at all of gaining seats.

I make no apologies for my support of the Monster Raving Loony Party in the last election.

In all seriousness, this is good civics, and I look forward to the rest of the series.

But unlike the US, the smaller parties in Germany actually have a chance to participate. Sure, SPD and CDU/CSU are the biggies, but at the moment the latter isn’t even in the governing coalition while the Greens and FDP, each of which got half the votes CDU/CSU got, are.

An amusing kerfuffle from the Bundestag: the far-right (I’d say neo-fascist) AfD has 82 seats, and they sit at the right side of the Bundestag. Traditionally the quasi-libertarian (by German standards) FDP would be seated immediately next to the AfD, but they didn’t want to be next to the AfD, and the seats got shuffled to put the CDU/CSU there instead. Needless to say, the CDU/CSU leadership was not happy about this.

(Not really related to the above, but I’m really looking forward to your post re: Duverger’s Law.)

@Mikey:

Hey, man: spoilers! 🙂

I have noticed this myself, and it drives me up the wall.