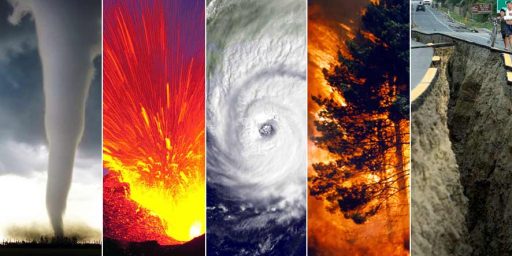

Humanity and Natural Disasters

Be prepared for the next disaster (John Schauble, The Age)

The enormity of the tragedy that struck the coastlines of southern Asia on Sunday will take months, if not years, to unfold. More immediately apparent, however, is that humans are slow learners when it comes to natural disasters. The massive humanitarian response now under way to alleviate the suffering of those affected by the earthquake and tsunamis that radiated out across the ocean off Sumatra mirrors a similar response after the Bam earthquake in Iran last year. Tragically, the international community will doubtless respond similarly again at some point in the near future. Yet on the scale of potential human catastrophe, the present crisis is nowhere near the “big one” that geohazard specialists and emergency planners fear. Natural disasters exact a devastating toll on the earth’s population every year. And there is ample evidence to suggest this trend will get worse before it gets better without government interventions, social and physical planning on a global scale.

*** Over the last decade of the 20th century, at least 1 billion people were directly affected by natural calamities. Even with better understanding of how disasters occur, the ballooning world population – mostly in the very areas most vulnerable to natural hazards – means that the human, if not economic, impacts have continued to rise exponentially. There are two factors that continue to influence mankind’s susceptibility to catastrophe. A doubling of the world’s population between 1960 and 2000, centred in developing countries, has pressed humans to invade those areas formerly regarded as marginal for agriculture and settlement: steep hillsides, flood plains and coastal zones. According to Professor Bill McGuire, director of the Benfield Greig Hazard Research Centre at University College London, “such terrains are clearly high-risk and can expect to succumb on a more frequent basis to landslides, flooding, storm surges and tsunamis”.

More startling, however, is the global trend towards urban settlement and the growth of megacities. The United Nations estimates that 60 per cent of the world’s population will live in cities by 2015. In Australia, 91 per cent already do, clustered along the coast. By next year there will be 19 cities with populations above 10 million: Tokyo the largest with 27 million followed by Sao Paulo, Brazil, also with more than 20 million. That some of these megacities also lie in hazard zones means that the prospect of mega-disasters with death tolls of 1 million or more also increases. Factor in unknowns, such as the impact of global warming and increasing water shortages around the world, and the future seems bleak.

There is something in the human psyche that compels us to deny the prospect of disaster on this scale. Many people cling to the belief that such events will happen to “someone else”. In the case of rare events such as tsunamis, the tendency is simply to deny the possibility or make a great show of ignoring it. When such an event does occur, there is often a need to seek someone to blame – usually government. The manner in which regional governments have been gently berated by the US Geological Service since Sunday’s catastrophe over their failure to have a tsunami warning system in the Indian Ocean is one example of this. The US established such a system in the Pacific after a huge tsunami event in Alaska in 1964. Yet the last tsunami of any consequence in the Indian Ocean followed the 1883 eruption of the Krakatoa volcano. It claimed 36,000 lives – but occurred well outside living memory. A warning system, even so, is no guarantee that lives will be saved.

Worth remembering. Of course, human decision-making could be improved. As Kevin Aylward notes, officials actually had warning of this disaster and ignored it:

Just minutes after the earthquake in the Indian Ocean on Sunday morning, Thailand’s foremost meteorological experts were sitting together in a crisis meeting. But they decided not to warn about the tsunami “out of courtesy to the tourist industry”, writes the Thailand daily newspaper The Nation.

*** …We finally decided not to do anything because the tourist season was in full swing. The hotels were 100% booked full. What if we issued a warning, which would have led to an evacuation, and nothing had happened. What would be the outcome? The tourist industry would be immediately hurt. Our department would not be able to endure a lawsuit…

Overeacting to a false alarm could be economically devastating. But, obviously, not as devastating as under-reacting to a legitimate one. In all fairness, though, the damage control that could have been done at that late stage was minimal. The equivalent of the American losses in the Vietnam War–suffered over the course of decades–was experienced in a few hours.

I’m not trying to sound completely callous and cold…but from the way I read history, mankind has ALWAYS lived precariously on the edge of survival, just barely hanging on. Too many people in the past 100 years have started to look upon life WITHOUT trouble, death, disease, starvation, etc (the 4 horseman?) as their right. The fact that life is so precarious should make us appreciate what blessings we DO have all the more.

The us casualties in vietnam were suffered over about a dozen years, not “decades.”

bryan,

Well, certainly, most of them were suffered from around 1966-1973. But we had forces in Vietnam /French Indochina from the end of WWII through 1975.

Capt. Harry Griffith Cramer, who died in October of 1957, was the first American killed in the war.

James,

so you’re going to go with the bell curve argument? I can’t imagine that there were many more between the years of 1957 and 1963, which was when i was thinking the counting should start. Before that point, the total number of deaths was less than 100.

Of course, now that I’m looking at this site:

http://thewall-usa.com/stats/#year

I see that we lost 400+ in 1978 (?), so I guess you are right.

Bryan,

No, I’m just noting that the casualties took place over a long period of time. Almost all of them were within a very short period, of course.

My guess is the 1978 deaths are people who subsequently died of wounds from the war. So far as I know, all U.S. troops were out by 1975. All but the POWs were out in 1973.