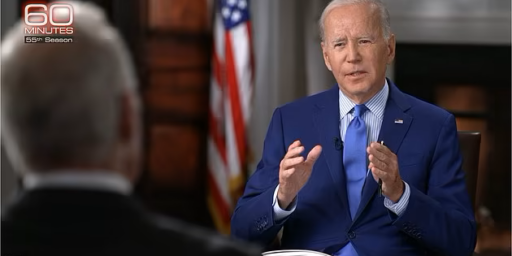

Biden’s Covid Malaise?

A pandemic hangover may be clouding American politics.

Lisa Lerer, Jennifer Medina, and Reid J. Epstein reporting for NYT (“How a Pandemic Malaise Is Shaping American Politics“):

In March 2020, when Joseph R. Biden Jr. and Donald J. Trump competed for the White House for the first time, American life became almost unrecognizable. A deadly virus and a public health lockdown remade daily routines with startling speed, leaving little time for the country to prepare.

Four years later, the coronavirus pandemic has largely receded from public attention and receives little discussion on the campaign trail. And yet, as the same two men run once again, Covid-19 quietly endures as a social and political force. Though diminished, the pandemic has become the background music of the presidential campaign trail, shaping how voters feel about the nation, the government and their politics.

How can it be that the pandemic has simultaneously “receded from public attention” and yet is “background music”?

Public confidence in institutions — the presidency, public schools, the criminal justice system, the news media, Congress — slumped in surveys in the aftermath of the pandemic and has yet to recover. The pandemic hardened voter distrust in government, a sentiment Mr. Trump and his allies are using to their advantage. Fears of political violence, even civil war, are at record highs, and rankings of the nation’s happiness at record lows. And views of the nation’s economy and confidence in the future remain bleak, even as the country has defied expectations of a recession.

I’m skeptical that all of these things are a result of the pandemic. And the American experience with COVID was so intertwined with Trump’s leadership that disaggregating the two is impossible.

“The pandemic pulled the rug from people — you were never quite as secure as you were,” Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York, a Democrat, said in an interview. “We’re starting to get our grounding back. But I think it’s just hard for people to feel good again.”

High rates of office vacancies have crippled urban downtowns, adding to the sense that the country has yet to recover fully. Depression and anxiety rates remain stubbornly high, particularly among young adults. Students remain behind in math and reading, part of the continued fallout from school closures. And even positive news has been met with skepticism: F.B.I. data released this month confirmed that crime declined significantly in 2023, though polling conducted at the end of last year has shown that voters believe otherwise.

Public perceptions of crime seldom track reality, as they’re shaped by news coverage. But the rest makes sense to me. The pandemic permanently shifted the nature of work, at least for white-collar types, and we’re still struggling to figure out the new normal. Routines were upended and many have not settled into new ones. Or, worse, the new ones leave them without daily contact with other humans.

Elected officials, strategists, historians and sociologists say the lasting effects of the pandemic are visible today in the debates over inflation, education, public health, college debt, crime and trust in American democracy itself. The lingering trauma from that time, they said, is contributing to a sense of national malaise that voters express in polling and focus groups — a kind of pandemic hangover that appears to be hurting Mr. Biden and helping Mr. Trump in their presidential rematch.

Mr. Biden’s administration passed a robust package of legislation and issued executive actions that steered the country out of the crisis, but voters give the president limited credit for his accomplishments and remain pessimistic about the economy and the nation’s direction. Mr. Trump oversaw the most acute phase of the pandemic, but he casts himself as having presided over a more prosperous and secure country, and continues to lead Mr. Biden in polls.

This strikes me as plausible. Indeed, even as one who is virulently anti-Trump and who voted for Biden, I don’t blame Trump for the COVID collapse* and give Biden relatively little credit for the recovery. People less tuned in remember low gas prices and cheap credit under Trump and are angry about higher food prices and high interest rates under Biden.

And this is unlikely to work:

Mr. Biden has defended his role in pulling the country out of a moment of profound calamity, using his State of the Union address to cast the pandemic as “the greatest comeback story never told.”

At a recent Dallas fund-raiser, the president blamed his predecessor for everything people remember with horror about the pandemic.

“Covid had come to America, and Trump was president,” Mr. Biden told donors, adding, “There was a ventilator shortage. Mobile morgues were being set up. Over — over a million people died. Our loved ones were dying all alone, and they couldn’t even say goodbye to them.”

Indeed, if his opponent weren’t such an awful excuse for a human being, I would find this line of attack outrageous. Of course, the biggest global pandemic in more than a century was going to be catastrophic. It’s just stupid to blame Trump for its coming to our shores.

Regardless, the narrative is significantly disrupted by this:

Any political discussion of the crisis is complicated by the widely different ways Americans experienced the most globally disruptive event in a generation.

There is no single unifying pandemic narrative. In California, New York and other Democratic-controlled states, schools and businesses maintained restrictions well into 2021. In Florida, Georgia, South Dakota and other Republican-run states, life resumed some semblance of normalcy far more quickly, even as death tolls mounted.

And, more importantly, this:

Since then, memories have been colored by partisan politics. One study published in Nature last year found that people’s recollections of the severity of the pandemic were skewed by the views they later held about vaccines.

“It was the first time in my lifetime that it felt like everything was up for grabs,” said Eric Klinenberg, a professor of sociology at New York University and the author of a new book about the pandemic in New York, “2020: One City, Seven People and the Year Everything Changed.” “Where we’re left today is this emotional experience of feeling like something is off in the country. We’re experiencing long Covid as a social disease.”

Frustrations over Mr. Biden’s handling of the pandemic and the post-pandemic recovery run deep among many Republicans, and even some Democrats.

Kristin Urquiza spoke at the Democratic National Convention in 2020 about her experience watching her father die from complications of Covid. She created a political advocacy group, Marked by Covid, and said she supported Mr. Biden in 2020 because she believed he would comfort victims and console families. She feels differently now.

“He broke his promise to care,” Ms. Urquiza said of the president.

Rather than coming out of the pandemic with a renewed sense of hope, the country has become a far less unified place, she said. She has been deeply frustrated that there have been no efforts to create a permanent national memorial for the more than 1.1 million Americans killed by the disease.

“The families I speak to — the ones living with long Covid and those who have lost loved ones — express a profound sense of abandonment,” Ms. Urquiza said.

For many Republican voters, the pandemic also hardened their belief that government does more harm than good.

Michael Jackson, 47, a waiter in Las Vegas who was out of work for nearly a year, was furious that much of the state did not reopen more quickly. “I think most politicians showed they are completely oblivious to what’s currently happening beyond their office,” Mr. Jackson said.

Dr. Mary Elizabeth Christian, a retired breast-cancer surgeon who lives in Baton Rouge, La., and is part of Ms. Urquiza’s Marked by Covid group, stayed isolated throughout the pandemic and still wears a mask in public. She avoids restaurants and some of her favorite pastimes, like attending gymnastics meets at Louisiana State University, for which she was a longtime season-ticket holder.

Her parents, who were vaccinated, broke their isolation for a dinner to celebrate their 62nd wedding anniversary in July 2021. Within three days, they both tested positive. They died within two days of each other that August.

Dr. Christian said she had lost trust in all levels of a government that she believes failed to protect its most vulnerable citizens.

“I have been a pretty stalwart pro-life Republican, and I can say that I was disappointed by the Republican Party,” said Dr. Christian, who added that she planned to vote for a third-party candidate this November. “I was very disappointed that a party that has a platform to defend life didn’t do what it took to defend the lives of people who were being exposed to Covid.”

That this is mostly nonsensical is immaterial. People feel how they feel.

Since taking office, Mr. Biden has won lasting legislative milestones, including a $1 trillion infrastructure package, a $1.9 trillion Covid relief package, and major investments to combat climate change.

But some of his post-pandemic programs with the biggest influence on people’s daily lives have not endured. Congress failed to renew a child tax credit payment that sent families monthly checks. Tens of millions of dollars in grants to assist child-care facilities expired, forcing the closure of some providers. Millions of borrowers who had their student loans paused during the pandemic now have payments due, after the Supreme Court rejected an administration plan to forgive $430 billion of student debt. The administration is now pursuing a more piecemeal approach to forgiving that debt.

Alida Garcia, a Democratic strategist and mother of twins, said she harbored a “fired-up rage” during the pandemic and felt almost constantly angry “about the lack of support for mothers in particular.”

“Now, I am equally, if not more, exhausted than at that time, and it feels like things are getting harder for women,” she said.

For others, the anger of those pandemic days has metastasized into a deeper lack of faith in politics.

Julie Fry, a public defender in New Jersey, spent months pushing administrators and politicians in her state to reopen shuttered public schools. Three years later, her young daughters are thriving in school.

But she feels angry and resentful — at politicians from both parties — when she recalls those long months of home-schooling and the mental health toll it took on so many children.

“I feel like Trump was a mess and Biden was a coward about doing what was right for kids,” said Ms. Fry, who describes herself as a staunch liberal. “There were no grown-ups willing to speak up for what kids needed.”

That Biden had next to no power over local public schools doesn’t matter, I guess. As I’ve been noting throughout the 21-year history of this site, people ascribe extraordinary power to the President, blaming him for seemingly everything wrong in the world and crediting him when things are going well.

Presumably coincidentally, Cornell psychiatrists George Makari and Richard A. Friedman take to The Atlantic to argue “It’s Not the Economy. It’s the Pandemic.”

America is in a funk, and no one seems to know why. Unemployment rates are lower than they’ve been in half a century and the stock market is sky-high, but poll after poll shows that voters are disgruntled. President Joe Biden’s approval rating has been hovering in the high 30s. Americans’ satisfaction with their personal lives—a measure that usually dips in times of economic uncertainty—is at a near-record low, according to Gallup polling. And nearly half of Americans surveyed in January said they were worse off than three years prior.

Experts have struggled to find a convincing explanation for this era of bad feelings. Maybe it’s the spate of inflation over the past couple of years, the immigration crisis at the border, or the brutal wars in Ukraine and Gaza. But even the people who claim to make sense of the political world acknowledge that these rational factors can’t fully account for America’s national malaise. We believe that’s because they’re overlooking a crucial factor.

Four years ago, the country was brought to its knees by a world-historic disaster. COVID-19 hospitalized nearly 7 million Americans and killed more than a million; it’s still killing hundreds each week. It shut down schools and forced people into social isolation. Almost overnight, most of the country was thrown into a state of high anxiety—then, soon enough, grief and mourning. But the country has not come together to sufficiently acknowledge the tragedy it endured. As clinical psychiatrists, we see the effects of such emotional turmoil every day, and we know that when it’s not properly processed, it can result in a general sense of unhappiness and anger—exactly the negative emotional state that might lead a nation to misperceive its fortunes.

Normally, when a spate of stories making a similar argument hit, it’s because an underlying big study came out. But neither article references one.

Regardless, Makari and Friedman aren’t doing political analysis here but highlighting the downsides of repressing trauma.

The pressure to simply move on from the horrors of 2020 is strong. Who wouldn’t love to awaken from that nightmare and pretend it never happened? Besides, humans have a knack for sanitizing our most painful memories. In a 2009 study, participants did a remarkably poor job of remembering how they felt in the days after the 9/11 attacks, likely because those memories were filtered through their current emotional state. Likewise, a study published in Nature last year found that people’s recall of the severity of the 2020 COVID threat was biased by their attitudes toward vaccines months or years later.

When faced with an overwhelming and painful reality like COVID, forgetting can be useful—even, to a degree, healthy. It allows people to temporarily put aside their fear and distress, and focus on the pleasures and demands of everyday life, which restores a sense of control. That way, their losses do not define them, but instead become manageable.

But consigning painful memories to the River Lethe also has clear drawbacks, especially as the months and years go by. Ignoring such experiences robs one of the opportunity to learn from them. In addition, negating painful memories and trying to proceed as if everything is normal contorts one’s emotional life and results in untoward effects. Researchers and clinicians working with combat veterans have shown how avoiding thinking or talking about an overwhelming and painful event can lead to free-floating sadness and anger, all of which can become attached to present circumstances.

[…]

Traumatic memories are notable for how they alter the ways people recall the past and consider the future. A recent brain-imaging study showed that when people with a history of trauma were prompted to return to those horrific events, a part of the brain was activated that is normally employed when one thinks about oneself in the present. In other words, the study suggests that the traumatic memory, when retrieved, came forth as if it were being relived during the study. Traumatic memory doesn’t feel like a historical event, but returns in an eternal present, disconnected from its origin, leaving its bearer searching for an explanation. And right on cue, everyday life offers plenty of unpleasant things to blame for those feelings—errant friends, the price of groceries, or the leadership of the country.

There’s more but you get the point. And, it turns out, there’s some political analysis after all:

One remedy is for leaders to encourage remembrance while providing accurate and trustworthy information about both the past and the present. In the early days of the pandemic, President Donald Trump mishandled the crisis and peddled misinformation about COVID. But with 2020 a traumatic blur, Trump seems to have become the beneficiary of our collective amnesia, and Biden the repository for lingering emotional discontent. Some of that misattribution could be addressed by returning to the shattering events of the past four years and remembering what Americans went through. This process of recall is emotionally cathartic, and if it’s done right, it can even help to replace distorted memories with more accurate ones.

President Biden invited the nation to grieve together in 2021, when American death counts reached 500,000, and again in 2022, when they surpassed 1 million. In his 2022 State of the Union address, he rightly acknowledged that “we meet tonight in an America that has lived through two of the hardest years this nation has ever faced,” before urging Americans to “move forward safely.” But in the past two years, he, like almost everyone else, has largely tried to proceed as if everyone is back to normal. Meanwhile, American minds and hearts simply aren’t ready—whether we realize it or not.

Perhaps Biden and his advisers fear that reminding voters of such a dark time would create more trouble for his presidency. And yet, our work leads us to believe that the effect would be exactly the opposite. Rituals of mourning and remembrance help people come together and share in their grief so that they can return more clear-eyed to face daily life. By prompting Americans to remember what we endured together, paradoxically, Biden could help free all of us to more fully experience the present.

Good luck with that.

*I, of course, blame him for his politicization of the virus and poor leadership throughout the crisis. But the economy was going to collapse even if he were a perfectly normal President taking expert advice and making the best decisions he could in the interest of the country.

It’s less malaise than clarity. The reaction to Covid fits closely with supersize vehicles and guns as an act of American selfishness which feeds on how divisive it was. The people who flipped out a month into the pandemic and the so-called lockdowns ended up getting high on their own supply. You can’t escape judgement for being a selfish jerk anymore than you can for driving a behemoth for no reason or owning 38 guns and never hunting once. American selfishness at its base level creates its own rift, because it’s so childish. People who spent their lives invoking WW2 and The Greatest Generation turned out to be incapable of wearing a mask in a grocery store for a year. You can blame Fauci and CDC failures but it’s really on that person and they know it.

The last time Americans as a whole suffered, really suffered, was probably the Great Depression. We don’t have wars on our territory, we have wars, ‘somewhere else.’ We’ve suffered less from terrorism proportionally than, say, Belgium. We’ve been a rich, secure country for a long time, for several generations. The last cohort of Americans familiar with real hardship are now in their 90’s.

That people actually lost their shit because of face masks was proof positive that we are a weak people, unprepared for hardship, easily frightened and frankly, rather pathetic. Jesus Christ, WTF would we do in a real plague, a repeat of the Spanish flu, for example. Or a war on US territory. Aliens don’t have to come in giant ships like Independence Day, hell we’d surrender to Grogu on a surfboard.

The OECD Better Life Index is a great resource. Not only does it allow for a deep(ish) dive on life in the USA, but it also makes for easy between-country comparisons. Indeed, it has a nifty “Compare to…” tool, which I consider a gentle nudge toward an oft-neglected but important question in these types of discussions: Compared to what?

@Mimai: That OECD data is fascinating. Thank you. Overall we are in a top tier that’s mostly the English Speaking countries except the UK and Scandinavia. Which is to say we are among the safest, most prosperous people the world has ever seen. And we’re pissed. Go figure.

The Trump worshiping lickspittles are doing everything that they can to groom the USA to accept Putin as our ally in the world. In the recent past these citizens would be called traitors. Today they are called Republicans.

This bit of conventional wisdom continues to annoy me. If it were true, states like California would have seen a much greater decline in scores than Florida. But there is no red-blue divide in the data, the scores decreased by give-or-take the same amount everywhere. There’s variation, but it doesn’t correlate to red-blue.

Putting the blame on school closures is also easy — we reopened the schools, so I guess the kids will be fine now. No need to look at the lingering effects of trauma, or infection, or anything difficult.

And this is emblematic of my thoughts on our country’s Covid response in general. We just want to pretend it didn’t happen, rather than deal with the consequences. No effort to get the kids back on track. No effort to improve air circulation in places of employment. No plan for people with long covid. Not even requiring masks in hospitals by and large.

This seems to be more throwing spaghetti at the wall and seeing what sticks when it comes to trying to explain why people aren’t behaving the way some expect.

Maybe if you look at it from a state level or “red vs blue” but the many studies that look at schools that closed or closed longer vs schools that did not have pretty much universally found that kids in the schools that closed longer had and continue to have worse outcomes.

And yes, even for schools that opened back up early, kids still had learning loss – it was just a lot less.

The kids who fared the worst from school closures were those who needed the school environment the most—poor kids who didn’t have a parent home during the day to help them and had no other options.

My kids were lucky because we are both educated and work from home. We could supervise them and also help them directly. My oldest son was doing so terribly with remote learning that we transferred him to a school in the district that had in-person learning four days a week. That turned him around 180 in the right direction. That was only possible because it was an option in our school district and we are higher SES parents willing to go through the hoops to do that.

Most people aren’t that fortunate, especially single parents with jobs who didn’t have the option of remote work.

There are efforts, but there’s a limit to what can be done. We could do comprehensive testing and hold kids with the most learning loss back a year. You could “track” students in the same grade so that those who are behind have more school time to focus on the subjects they are behind on. You could have extra instruction/work time built into the school day, or after school for kids to catch up.

None of those are very popular, especially with the organizations and people who were the most pro-closure.

Anyway, regarding the Covid malaise, we probably should mention Larry Summer’s theory that it’s about interest rates and the cost of money.

I’m sure that’s a factor, but probably doesn’t explain the whole dynamic.