Treating COVID Like the Flu

New CDC guidelines acknowledge the political realities.

As expected, the CDC has loosened longstanding rules around COVID. WaPo (“CDC officially drops five-day covid isolation guidelines“):

Americans who test positive for the coronavirus no longer need to routinely stay home from work and school for five days under new guidance released Friday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The agency is loosening its covid isolation recommendations for the first time since 2021 to reflect the changing landscape of covid-19 four years after the virus emerged. The CDC laid out its justification for the guidance change in a 25-page document that describes the evolving risk environment. Although coronavirus infections are continuing at levels similar to those in years past, new infections are now causing less severe illness and far fewer hospitalizations or deaths, CDC data shows.

The change, as reported by The Washington Post last month, is effective immediately, CDC officials said. The agency said itis streamlining its guidance for respiratory viral illnesses, and the new recommendations bring covid-19 in line with how other common viruses, such as influenza and RSV, are managed.

“Our goal here is to protect those at risk for severe illness while also reassuring folks that these recommendations are simple, clear, easy to understand and can be followed,” CDC Director Mandy Cohen said during a media briefing Friday. The change, she added, “reflectsthe progress we’ve made in protecting against severe illness from covid.”

The basic advice is the same: Stay home and away from others when you’re sick. Under the new approach, people who test positive for the coronavirus no longer need to isolate at home if they have been fever-free for at least 24 hours without the aid of medication and their overall symptoms are improving.

Once people resume normal activities, the updated guidance encourages them to take additional preventive steps for the next five days to curb disease spread. These include improving ventilation by opening windows to bring in fresh outside air or purifying indoor air, washing hands often and cleaning frequently touched surfaces, wearing a well-fitting mask, keeping a distance from others, and continuing to test ahead of any gatherings, CDC officials said.

“Testing as soon as you have symptoms can help you take precautions early, and if you test positive, seeking treatment, avoiding contact with people at a higher risk of getting seriously ill, namely those 65 and older, and masking for five days after you feel better will all help reduce transmission and will protect others from covid-19,” said Ashwin Vasan, the top public health official for New York City, which plans to update its isolation guidance to align with the CDC’s.

Not all respiratory infections result in fever, so paying attention to other symptoms, such as cough and muscle aches, is important as someone determines when they are well enough to leave home, according to the CDC.

Giving people symptom-based guidance is a better way to prioritize those most at risk and balance the potential for disruptive impacts on schools and workplaces, health officials and experts have said. The federal recommendations follow similar moves by Oregon and California. California shortened its five-day isolation recommendation in January; Oregon made a similar move last May.

Other countries have implemented similar guidance, including Britain, Australia, France and Canada, and found no significant change in spread or severe disease, according to a CDC blog post on the respiratory guidance.

Despite being long anticipated, not everyone is happy. The Atlantic‘s Katherine J. Wu wonders, “Why Are We Still Flu-ifying COVID?” Writing two days before the official announcement, she lamented,

Four years after what was once the “novel coronavirus” was declared a pandemic, COVID remains the most dangerous infectious respiratory illness regularly circulating in the U.S. But a glance at the United States’ most prominent COVID policies can give the impression that the disease is just another seasonal flu. COVID vaccines are now reformulated annually, and recommended in the autumn for everyone over the age of six months, just like flu shots; tests and treatments for the disease are steadily being commercialized, like our armamentarium against flu. And the CDC is reportedly considering more flu-esque isolation guidance for COVID: Stay home ’til you’re feeling better and are, for at least a day, fever-free without meds.

These changes are a stark departure from the earliest days of the crisis, when public-health experts excoriated public figures—among them, former President Donald Trump—for evoking flu to minimize COVID deaths and dismiss mitigation strategies. COVID might still carry a bigger burden than flu, but COVID policies are getting more flu-ified.

There’s a good reason for that!

In some ways, as the population’s immunity has increased, COVID has become more flu-like, says Roby Bhattacharyya, a microbiologist and an infectious-disease physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Every winter seems to bring a COVID peak, but the virus is now much less likely to hospitalize or kill us, and somewhat less likely to cause long-term illness. People develop symptoms sooner after infection, and, especially if they’re vaccinated, are less likely to be as sick for as long. COVID patients are no longer overwhelming hospitals; those who do develop severe COVID tend to be those made more vulnerable by age or other health issues.

So, what’s Wu’s problem?

Even so, COVID and the flu are nowhere near the same. SARS-CoV-2 still spikes in non-winter seasons and simmers throughout the rest of the year. In 2023, COVID hospitalized more than 900,000 Americans and killed 75,000; the worst flu season of the past decade hospitalized 200,000 fewer people and resulted in 23,000 fewer deaths. A recent CDC survey reported that more than 5 percent of American adults are currently experiencing long COVID, which cannot be fully prevented by vaccination or treatment, and for which there is no cure. Plus, scientists simply understand much less about the coronavirus than flu viruses. Its patterns of spread, its evolution, and the durability of our immunity against it all may continue to change.

And yet, the CDC and White House continue to fold COVID in with other long-standing seasonal respiratory infections. When the nation’s authorities start to match the precautions taken against COVID with those for flu, RSV, or common colds, it implies “that the risks are the same,” Saskia Popescu, an epidemiologist at the University of Maryland, told me. Some of those decisions are “not completely unreasonable,” says Costi Sifri, the director of hospital epidemiology at UVA Health, especially on a case-by-case basis. But taken together, they show how bent America has been on treating COVID as a run-of-the-mill disease—making it impossible to manage the illness whose devastation has defined the 2020s.

Each “not completely unreasonable” decision has trade-offs. Piggybacking COVID vaccines onto flu shots, for instance, is convenient: Although COVID-vaccination rates still lag those of flu, they might be even lower if no one could predict when shots might show up. But such convenience may come at the cost of protecting Americans against COVID’s year-round threat. Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, told me that a once-a-year vaccine policy is “dead wrong … There is no damn evidence this is a seasonal virus yet.” Safeguards against infection and milder illness start to fade within months, leaving people who dose up in autumn potentially more susceptible to exposures by spring. That said, experts are still torn on the benefits of administering the same vaccine more than once a year—especially to a public that’s largely unwilling to get it.

So, clearly, a one-size-fits-all policy for COVID is a mistake. The most vulnerable populations need different protocols than the rest of us. Which, it turns out, is what CDC is essentially recommending.

Throughout the pandemic, immunocompromised people have been able to get extra shots. And today, an advisory committee to the CDC voted to recommend that older adults once again get an additional dose of the most recently updated COVID vaccine in the coming months. Neither is a pattern that flu vaccines follow.

So, again, what’s the problem?

Dropping the current COVID-isolation guideline—which has, since the end of 2021, recommended that people cloister for five days—may likewise be dangerous. Many Americans have long abandoned this isolation timeline, but given how new COVID is to both humanity and science, symptoms alone don’t yet seem enough to determine when mingling is safe, Popescu said. (The dangers are even tougher to gauge for infected people who never develop fevers or other symptoms at all.) Researchers don’t currently have a clear picture of how long people can transmit the virus once they get sick, Sifri told me. For most respiratory illnesses, fevers show up relatively early in infection, which is generally when people pose the most transmission risk, says Aubree Gordon, an epidemiologist at the University of Michigan. But although SARS-CoV-2 adheres to this same rough timeline, infected people can shed the virus after their symptoms begin to resolve and are “definitely shedding longer than what you would usually see for flu,” Gordon told me. (Asked about the specifics and precise timing of the update, a CDC spokesperson told me that there were “no updates to COVID guidelines to announce at this time,” and did not respond to questions about how flu precedents had influenced new recommendations.)

At the very least, Emily Landon, an infectious-disease physician at the University of Chicago, told me, recommendations for all respiratory illnesses should tell freshly de-isolated people to mask for several days when they’re around others indoors; she would support some change to isolation recommendations with this caveat. But if the CDC aligns the policy fully with its flu policy, it might not mention masking at all.

But, here, the problem isn’t so much “flu-ifying” the policy but our broader cultural aversion to masking. Many societies, notably those in East Asia, have established a tradition of masking to prevent the spread of the flu and other airborne diseases. Western societies—not just ours—have proven averse to doing so.

Beyond that, it’s not at all obvious what we can or should do about people who are infected with COVID (or the flu!) but aren’t experiencing symptoms. It’s really unfortunate that they’re spreading disease but I haven’t the foggiest what sort of protocols we could reasonably adopt to prevent people who don’t know they’re sick from going out in public.

Several experts told me symptom-based isolation might also remove remaining incentives to test for the coronavirus: There’s little point if the guidelines for all respiratory illnesses are essentially the same. To be fair, Americans have already been testing less frequently—in some cases, to avoid COVID-specific requirements to stay away from work or school. And Osterholm and Gordon told me that, at this point in the pandemic, they agree that keeping people at home for five days isn’t sustainable—especially without paid sick leave, and particularly not for health-care workers, who are in short supply during the height of respiratory-virus season.

That’s a very different issue. But solving it actually requires doing so along with the same issues with respect to the flu, the common cold, and other viral diseases. If people can’t afford to stay home—whether to care for themselves or their sick children—they’re not going to do so.

But the less people test, the less they’ll be diagnosed—and the less they’ll benefit from antivirals such as Paxlovid, which work best when administered early. Sifri worries that this pattern could yield another parallel to flu, for which many providers hesitate to prescribe Tamiflu, debating its effectiveness. Paxlovid use is already shaky; both antivirals may end up chronically underutilized.

Again, this isn’t a consequence of the CDC’s policy shift but of the culture of the medical community. And, while I claim no medical expertise, the debates around Tamiflu and Paxlovid strike me as legitimate—both as to their effectiveness as well as to the downside risks associated with side effects and cost.

Flu-ification also threatens to further stigmatize long COVID. Other respiratory infections, including flu, have been documented triggering long-term illness, but potentially at lower rates, and to different degrees than SARS-CoV-2 currently does. Folding this new virus in with the rest could make long COVID seem all the more negligible. What’s more, fewer tests and fewer COVID diagnoses could make it much harder to connect any chronic symptoms to this coronavirus, keeping patients out of long-COVID clinics—or reinforcing a false portrait of the condition’s rarity.

Given its prevalence, long COVID is wildly under-discussed, at least in the popular press and by our political leaders. At this point, it strikes me as the main difference between the flu and COVID for those of us who are vaccinated and relatively healthy.

Regardless, Wu’s argument against flu-ification actually reinforces the parallels between the diseases:

The U.S. does continue to treat COVID differently from flu in a few ways. Certain COVID products remain more available; some precautions in health-care settings remain stricter. But these differences, too, will likely continue to fade, even as COVID’s burden persists. Tests, vaccines, and treatments are slowly commercializing; as demand for them drops, supply may too. And several experts told me that they wouldn’t be surprised if hospitals, too, soon flu-ify their COVID policies even more, for instance by allowing recently infected employees to return to work once they’re fever-free.

Early in the pandemic, public-health experts hoped that COVID’s tragedies would prompt a rethinking of all respiratory illnesses. The pandemic showed what mitigations could do: During the first year of the crisis, isolation, masking, distancing, and shutdowns brought flu transmission to a near halt, and may have driven an entire lineage of the virus to extinction—something “that never, in my wildest dreams, did I ever think would be possible,” Landon told me.

Most of those measures weren’t sustainable. But America’s leaders blew right past a middle ground. The U.S. could have built and maintained systems in which everyone had free access to treatments, tests, and vaccines for a longer list of pathogens; it might have invested in widespread ventilation improvements, or enacted universal sick leave. American homes might have been stocked with tests for a multitude of infectious microbes, and masks to wear when people started to cough. Vaccine requirements in health-care settings and schools might have expanded. Instead, “we seem to be in a more 2019-like place than a future where we’re preventing giving each other colds as much as we could,” Bhattacharyya told me.

That means a return to a world in which tens of thousands of Americans die each year of flu and RSV, as they did in the 2010s. With COVID here to stay, every winter for the foreseeable future will layer on yet another respiratory virus—and a particularly deadly, disabling, and transmissible one at that. The math is simple: “The risk has overall increased for everyone,” Landon said. That straightforward addition could have inspired us to expand our capacity for preserving health and life. Instead, our tolerance for suffering seems to be the only thing that’s grown.

Wu and the cited experts on her side of this debate make strong points. But this reinforces a conclusion I came to fairly early in the pandemic: there’s a tension between “the science” and public health policy, with the latter constrained by the art of the possible.

If our main goal as a society is to minimize the spread of COVID, flu, and other communicable diseases, we should act much differently than we do. Masking should be routine in public spaces. Probably even in private homes occupied by more than one person. Nobody should leave the house if they’re the least bit under the weather. And we should probably be getting COVID vaccines every few months, not annually.

The reality, though, is that most people aren’t willing to live that way. And it’s not just idiot Trumpers or, indeed, even gauche Americans. Most of the world has simply long moved past taking extraordinary precautions against a rapidly-evolving virus that is likely always going to be a fact of life.

Given that, the CDC guidelines—which, again, mirror those in most of the developed world—make sense. Convince Americans to get a booster once a year, along with a flu shot, to maximize herd immunity in a relatively convenient fashion. Encourage those who are sick to stay home and take other reasonable steps to avoid spreading infection. Urge those who are most vulnerable or care for the most vulnerable to take additional precautions.

Is it perfect? Nope. But here as often, the perfect would be the enemy of the good.

I’ve already seen Facebook posts screeching “See? We TOLD you it was all a lie!”

This move will be taken as evidence that Big Government and Eevil Fauci were deceiving us all along.

There’s not much point in laws or guidelines no one is going to obey.

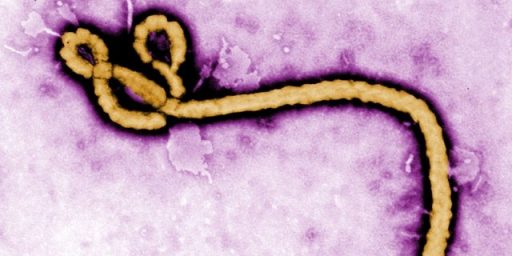

Americans have turned out to be remarkably fragile people. We have one half-assed pandemic – it ain’t cholera or ebola or the plague – and the country loses its collective mind.

The reality is that the real new guideline is to go to work sick with covid because the billionaires have decided that half a million covid deaths per year is a small sacrifice to pay in the name of profit.

Ironically, I just got covid two weeks ago and spent a big chunk of last week at home recovering. Even under the old guidelines I ended up having to have a big discussion with management, because while it was clear I was supposed to stay out somewhere between five and ten days, the precise criteria for when to return was clear as mud.

@Stormy Dragon:

The criteria should be: the day after a second consecutive negative test. Or at least the day after a negative test.

I claimed a time or two million, that whenever we lowered our guard against the trump virus, it went to town on us.

Somehow, I doubt abject surrender will work any better. Surrender only makes sense if the other side intends, or even can, stop fighting you.

There. FTFY.

Really, all I want as a general matter is that symptomatic people would stay home to protect the rest of us from their germs instead of oh, I don’t know, coming to day-long meetings in relatively small rooms full of other people.

I would like people to recognize that sick leave is not just for the sick person to get better, but to keep the sick person from infecting the rest of us. I would like employers to recognize this and provide adequate paid sick leave.

And I would like people to realize that coming to work sick is being an asshole, not showing how John Wayne you are.

It took nearly four years, but I finally got COVID a few weeks back. My entire strategy around COVID has been to delay getting it as long as possible with the hope that it would be as meaningless as the flu – mission accomplished. I was sick for a day or so, took Paxlovid for five days, and recovered immediately after the first dose (except for that horrible taste in my mouth from the drug). After the course of antivirals, I had a 1-1/2 day “bounce” of feeling tired. Two weeks or so from diagnosis I was back at 100% with no lingering effects.

A COVID-19 diagnosis today is a very different thing than it was before vaccines and antiviral treatments and dozens of major and minor mutations making it less severe and more contagious.

I’m pleased the CDC is adjusting to the real threat level.

@Steven L. Taylor: The “John Wayne” attitude is certainly affected by our lack of even a tiny social safety net for folks who have to miss work.

It’s easy for those of us who have had corporate/government/academia desk jobs all our lives to forget that missing a day’s work is a BIG deal for folks who don’t get paid unless they work, and who need every dime to meet their expenses.

If capitalists are going to siphon up every spare dollar, then they can’t complain when people come to work sick.

@Kathy:

The problem is the home tests test for COVID antigens, not the COVID virus, so they’re good for telling when the infection starts, but not when it ends. Your immune system can still be producing antigens weeks after the virus is gone. Most people can’t afford to miss a month of work.

@Steven L. Taylor:

For most diseases, this would be great. But the trump disease, never forget, gets transmitted before symptoms develop. The problem is how to know one is carrying the trump virus if one has no symptoms. Especially now that testing is really low.

@Stormy Dragon:

I need to look into this a bit, but the immune system does not produce antigens, it recognizes them as such. Antigen is short for “antibody generator.” This means any part of a virus or bacteria that leads the immune system, through a rather complex process, to make antibodies against it.

What I’m not sure is what “antigen test” means. Are there antigens on the test which will react with immune system cells in the sample? Or are there receptors in the test that can detect antigens?

Antibody tests, for example, contain virus sub-units that cause antibodies to bind to them. Therefore such tests detect antibodies, but don’t use antibodies for testing.

Did I ever mention biology is messy, and human use of language tends to make it more confusing?

@Kathy:

Sorry, I may be misunderstanding then (biology has always been one of my weak points). I’m not sure the reason then, but I was told that a certain amount of time after you start testing positive, you’re no longer infectious even if you’re still testing positive which can continue for up to 20 days for some people.

The last fifty years have seen the emergence of a number of infectious diseases, Legionnaires, Lyme, MRSA, C. diff, and others. Most of these disorders have not required widespread public action. The disorders that needed mobilization by a large segment of the public encountered resistance which in my opinion was often a puerile heel stomping. I recall activists that were very opposed to shutting the bath houses in the early days of the HIV epidemic. Our recent Covid outbreak encountered a political movement searching for wedge issues. Flu-ification is a problem because it ignores the fact that the 1918 flu killed 50 million (or so) people and left a lot of survivors with neurological sequelae. The flu was and is a big deal. More flu like illness is a bad thing.

Some novel disease is out there in the not too distant future, and turning public health into a political football won’t help. Of course, it might not need to be a novel virus; the public health officials of Florida appear to be working to measlefy the measles.

We are codifying what people are already mostly doing. However, if you are febrile you can now legitimately stay home. The virus and its effects have definitely changed. The risk is much lower. The guidelines do address those at high risk. I think that this was the best we could achieve and it’s largely appropriate. You can still wear a mask if you want when needed but it’s going to be the decision of the individual.

Steve

@Steven L. Taylor:

To be fair, John Wayne was an asshole.

@Stormy Dragon:

Don’t be sorry. Getting things a little wrong is how we learn best.

This trump of a virus has a long history of confounding us vaunted superior animals. Plus I do recall sometime in 2021 a coworker had mild symptoms, but kept testing positive for around 3 weeks, even after the symptoms subsided.

@Tony W:

For most people. But do please follow that link in the OP about long COVID. Wu said “A recent CDC survey reported that more than 5 percent of American adults are currently experiencing long COVID”, but that drastically understates what the report actually shows. Somewhere between 15% and 20% of all American adults have had a COVID experience that lasted 3 months or more, and vaccination has not affected those rates. For many, long COVID shows every sign of being a permanent disability.

Millions (tens of millions?) of permanently impaired adults is not, in any way, flu-like.

@Tony W:

This is also a place where American conservative intuitions are just flat wrong. The impact of paid sick leave on business profitability has been well-studied, and the overwhelming finding is that businesses in labor-intensive industries become more profitable when they introduce paid sick-leave programs. The “extra” costs are more than offset by the increased workforce availability and productivity when working.

Of course, this fact flies in the face of what conservatives want to be true, and we all know how that ends…

@DrDaveT:

You are probably right but we dont really know. I remember a researcher who specialized in respiratory viruses commenting that COVID is being researched so much more than anything in the past that we don’t really know whether certain manifestations are unique to COVID or common across many infections. And something like long COVID manifests similarly to a very common complaint: a combination of fatigue, low energy, and depression.

@Tony W: Understand I am griping about people who have real sick leave. I fully understand those who don’t.

@Gustopher: You have a point.

Here’s a short video explaining how antigen tests work.

Definitely they detect antigens present in a virus. They don’t use antigens to perform tests.

@Kathy:

Correct, the test detects a chunk of the virus – now if the immune system is doing its job, those chunks can be present but the virus itself isn’t functional (because it has host antibodies bound to it, for example). Basically, a negative test is an all clear, while a positive means there are still virus bits around, but does not demonstrate contagiousness (either for or against).

Still, I doubt anyone from the CDC wants to share an office, maskless, with someone who tested positive yesterday but feels “fine” with no fever today. It’s ridiculous. My description of this is “no restrictions, just vibes” and it’s dumb as hell.

@Steven L. Taylor: This is an excellent example of why that shouldn’t be a distinction. I don’t want to go to McDonalds or Chipotle and have my food prepared by a person who couldn’t afford to call in sick – no thank you.

Now let’s do healthcare.

Long COVID and damage to the immune system. My two younger brothers can’t taste, can’t smell, and can hardly walk more than a few blocks without getting exhausted, 4 years after catching COVID. One was a ground pounder in the 82nd Airborne and the other a forward artillery observer and cross country runner—not your ordinary lame citizens.

Today, both of them are essentially crippled, and it looks like they will be for life.

I had it after being vaccinated and for 8 months after COVID I had palpitations.

Every time you catch it your chances of developing Long COVID (systemic damage) or immune system damage increases, according to things I’ve read.

We are headed to a society of crippled people.

@Tony W: Like I said in my original comment.