Biden’s Entirely Normal Vacancies

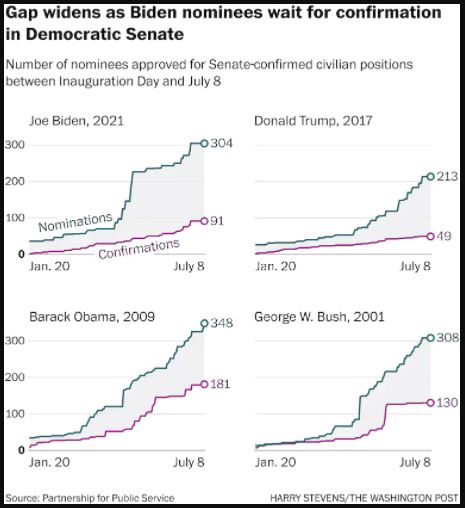

He has nominated only 304 people out 1,200+ that require Senate confirmation.

The Washington Post‘s report “Vacancies remain in key Biden administration positions” dramatizes the fact that, almost six months into a new administration, the vast number of presidentially-appointed positions remain unfilled:

The Biden administration is working to move past the pandemic without a permanent leader for the agency that authorizes drugs and vaccines. Democrats are decrying Republican-led efforts to restrict the right to vote, but President Biden has yet to nominate a solicitor general to represent the government on voting rights and other issues that could come before the Supreme Court.

And the Office of Management and Budget has only an acting director, even as the president seeks a sweeping budget resolution in Congress that would enable his “human infrastructure” plan to pass, one of his top goals.

Biden and his aides consistently tout their “whole of government” approach to solving pressing problems, but several key agencies across the government still have no permanent leaders. As the president approaches six months in office, some of those positions have direct involvement in addressing the crises Biden promised to prioritize at the start of his administration: the pandemic, the economy, climate change and racial inequity.

This is indeed problematic and, as detailed quite well in the report, truly complicates getting the President’s priorities executed by the bureaucracy and getting legislation passed by Congress. One has to read beyond the point where many readers will have lost interest, though, to get to this:

Biden is hardly the first incoming president to struggle with filling key positions. Any new administration faces hundreds of openings at the same time it’s grappling with other urgent challenges. Biden’s pace of nominations is faster than Donald Trump’s, slower than Barack Obama’s and about the same as George W. Bush’s — though unlike any of those three, Biden has decades of Washington contacts to draw on.

In terms of confirmations, Biden is doing quite poorly compared to recent “normal” presidents. (Trump was an outlier in that he deliberately chose not to fill vacancies because he inexplicably thought that would weaken agencies he didn’t like, rather than having them run on autopilot. Additionally, he was the anti-Biden in that he not only had no acolytes in Washington but most of the Republican establishment was loathe to work for him.) But that’s mostly a function of an opposite-party Senate and an incredibly poisonous climate. In terms of nominations, the only thing Biden can really control, he’s doing just fine.

Still, there’s a lot of work to do:

Biden has nominated 304 people out of more than 1,200 civilian positions that require Senate confirmation, according to data compiled by the Partnership for Public Service. Of those, 91 have been confirmed in a Senate that is split 50-50 between the parties with Vice President Harris casting tiebreaking votes.

You’ll note multiple references to the Partnership for Public Service, a nonpartisan organization that promotes the virtues of, well, public service, as defined by working in government in non-elected roles. The report seems essentially a PPS press release that’s been repackaged.

Again, they’re not wrong: it’s highly problematic that we probably won’t have a full Biden team in place for quite some time. And the 1200ish Senate-confirmed posts are just a fraction of the 7000-odd presidentially-appointed posts in the Plum Book. I haven’t the foggiest idea how many of those posts are still vacant or how it compares to past administrations.

My longstanding view is that this number should be trimmed radically. But that’s easier said than done since Presidents naturally want people in policy-determining posts who share their policy preferences.

Much later in the report, we get to something that is in fact a departure from the norm:

Several other names have been floated for FDA chief, a search that has also been slowed, in part, by the White House’s effort to select diverse candidates. Only two women have ever been the permanent administrator of the agency, and there has never been a top administrator of color.

Joshua Sharfstein, a former top FDA official who is now a vice dean at Johns Hopkins University, has been mentioned from the outset. Other names have included Michelle McMurry-Heath, a former FDA official who heads the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, an industry trade group, and Florence Houn, a former agency official who worked for the drug company Celgene and is now a consultant.

But it is not clear if any of them are still in the running, and selecting a nominee with ties to the drug industry could be tricky in the current political climate.

Diversity concerns have also complicated the nomination for OMB director. Biden initially nominated Neera Tanden, a former senior adviser to Hillary Clinton, but she withdrew after senators objected to her previous biting criticism of their colleagues on Twitter. The White House then named Deputy Director Shalanda Young, a popular figure on Capitol Hill, to serve as acting director of the office.

Young, who is African American, immediately became the front-runner to get the job permanently. But Asian American groups, disappointed with the lack of representation in Biden’s Cabinet, have pushed the president to replace Tanden, who is Indian American, with another nominee of Asian descent.

They have coalesced behind Nani Coloretti, who served in the Obama administration, but the Biden White House, which has shown disdain for public campaigning for positions, has not signaled any urgency to move on the nomination.

There are several other examples given but you get the point. We’ve already seen this fight playing out even in the highest-level posts, including Defense Secretary. While representation issues have been part of the picture going back at least to Bill Clinton’s pledge to appoint “a Cabinet that looks like America,” they have been more prominent and contentious in this administration.

Still, it’s not like internecine partisan fights haven’t long played out in the appointment process. Taking the politics out of politics is simply not possible and, to some extent, isn’t even desirable.

The problem starts with; There are too many positions that require Senate approval.

Even if a President on their second day in office, sent a full slate of nominees to the Senate, it would still take 3 years for them to be approved. The senate has what, a 3 day workweek? Many of these nominees will simply be rubber stamped and if that is the case those positions don’t require Senate review.

@Sleeping Dog:

Trump said he liked to appoint “acting heads” because they didn’t require senate confirmation. It was part of his attempt to create, deliberately, an uncertain and chaotic working environment.