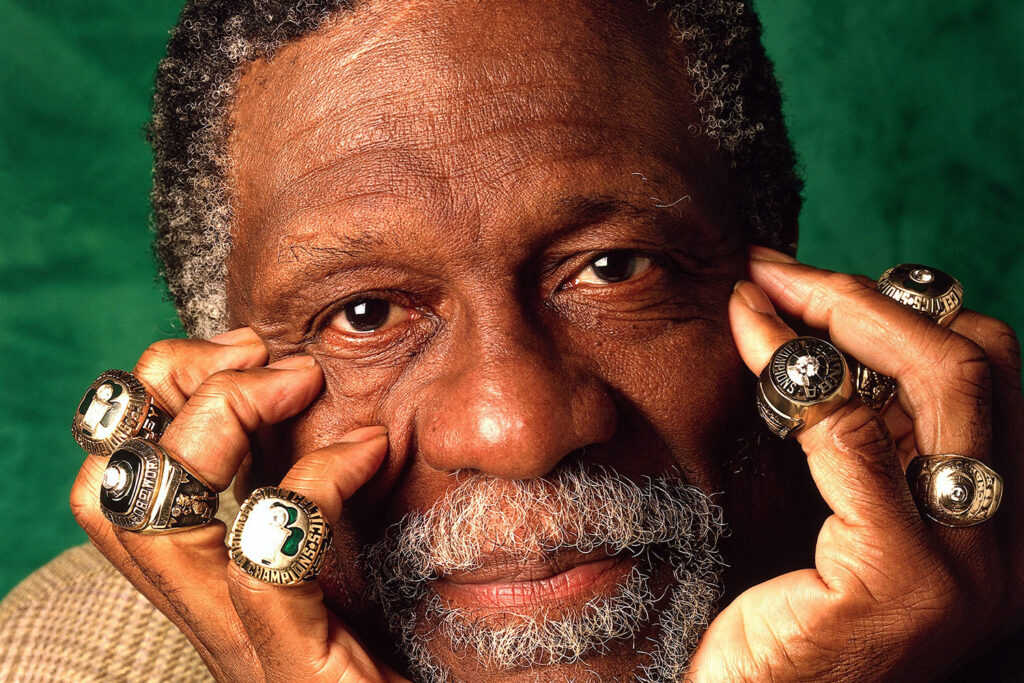

Bill Russell, 1934-2022

The iconic basketball player, coach, and civil rights leader is gone at 88.

Yesterday was a busy day, marking both the start of a new academic year at work and my oldest stepdaughter’s 23rd birthday, but I would be remiss not to note the passing of a legendary figure.

Washington Post (“Bill Russell, basketball great who worked for civil rights, dies at 88“):

Throughout his basketball career, Bill Russell compiled a legacy of championship achievement unparalleled in any sport. As the dominant defensive player of his generation, he won an Olympic gold medal for the U.S. basketball team in 1956, then over the next 13 years led the Boston Celtics to 11 NBA championships.

As the cornerstone of the franchise’s dynasty of the 1950s and 1960s, Mr. Russell won enduring renown as the most successful player in the history of team sports. When the Celtics named him head coach in 1966, he became the first Black man to hold that role in a major professional sport in the United States.

Mr. Russell, who died July 31 at 88, was indomitable on and off the court and one of the most fascinating public figures to straddle sports and civil rights. He was intensely driven and innovative as an athlete, notably when pitted in electrifying matchups against Wilt Chamberlain, the dominant scorer of the era. Their rivalry elevated the popularity of the National Basketball Association.

In his prime, the goateed, broad-shouldered Mr. Russell was 220 pounds of lean muscle stretched over a 6-foot-9 frame. Fast and agile, he had a superior vertical leap and used his 7-foot-4 wingspan to block shots with his arm outstretched like a bowsprit. With his athletic shot-blocking and rebounding skills, he revolutionized the way basketball was played on defense.

Mr. Russell’s physical gifts were complemented by an intellectual curiosity about other aspects of the game, such as shot trajectory, rebounding angles, human psychology and gamesmanship. He was known to needle opponents on the court, engage in trash talk, research players’ habits and aggressively block shots early in games. He once wrote that he knew he couldn’t block all shots but that a few resounding blocks were more than enough to throw an opposing player off his game.

“The only thing we know for sure about superiority in sports in the United States of America in the 20th century,” journalist Frank Deford wrote in Sports Illustrated in 1999, “is that Bill Russell and the Boston Celtics teams he led stand alone as the ultimate winners.”

Amid the celebration of his prowess as a player, Mr. Russell also struggled with the festering problems of prejudice and segregation. Born in the Jim Crow South, he was often described as private, introspective, prickly and principled, a man who searched for ways, as he once wrote in a book introduction, for his children to grow up “as we could not … equal … and understanding.”

As early as 1958, he accused the NBA of using a quota system to limit the number of Black players on each team. He took part in civil rights marches with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. but questioned the nonviolent strategy of the movement, arguing that African Americans had a right to defend themselves.

When civil rights leader Medgar Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Miss., in 1963, Mr. Russell accepted an offer by Evers’s older brother, Charles, to run a youth basketball camp in Jackson, to bring White and Black children together. He received death threats but refused to back away from his views.

Mr. Russell’s steely outward personality and pointed manner of speaking didn’t endear him to some fans in Boston, which had a long history of racism. The Boston Red Sox baseball team didn’t integrate until 1959, and protests in Boston over federal court-ordered school desegregation in the 1970s were among the most violent in the country.

Many fans perceived Mr. Russell to be aloof because for years he refused to sign autographs, preferring a handshake and conversation. He described Boston as a “flea market of racism” in his 1979 book, “Second Wind: Memoirs of an Opinionated Man.”

Despite his success with the Celtics — the team had never won a championship before his arrival — Mr. Russell did not receive local business endorsements and found himself shut out of exclusive neighborhoods when he was looking to buy a house. In 1968, his suburban Boston home was broken into and ransacked. Racial epithets were written on the walls, and feces were left on his bed.

“It had all varieties, old and new, and in their most virulent form,” he wrote in “Second Wind.” “The city had corrupt, city hall-crony racists, brick-throwing, send-’em-back-to-Africa racists, and in the university areas phony radical-chic racists. … Other than that, I liked the city.”

He refused to sign off on a public ceremony in 1972 to retire his Celtics jersey, and in 1975 he declined to attend his induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, upset that he would be the first African American player to be enshrined.

“We foolishly lionize athletes and make them heroes because they can hit a ball or catch one,” Mr. Russell once said. “The only athletes we should bother with attaching any particular importance to are those like [Muhammad] Ali, whom we can admire for themselves and not for their incidental athletic abilities.”

In 2010, President Barack Obama awarded Mr. Russell the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, for both his athletic accomplishments and his advocacy for human rights.

A fellow legend, Lakers star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, reflects on “The Bill Russell I Knew for 60 Years.”

When I learned that my friend Bill Russell had died, I tweeted this response: “Bill Russell was the quintessential Big Man—not because of his height but because of the size of his heart. In basketball he showed us how to play with grace and passion. In life he showed us how to live with compassion and joy. He was my friend, my mentor, my role model.”

That’s as much truth as I could fit into 272 characters (with spaces). But there is a whole lot more truth and love and respect in my 60-year relationship with Bill Russell that I want to share so the world can know him, not just as one of the greatest basketball players to ever live, but as a man who taught me how to be bigger—as a player and as a man.

I’ll let you read the tribute for yourself, but this passage stands out:

I always knew I wanted to be active in civil rights, but I didn’t always know how I would do that. I had attended some anti-war and civil rights protests rallies while at UCLA, but I knew that wasn’t enough. In 1967, when I was 20 years old, football legend turned Hollywood actor Jim Brown asked me to join what became known as the Cleveland Summit. We were a group of mostly Black athletes—including Bill Russell, Carl Stokes, Walter Beach, Bobby Mitchell, Sid Williams, Curtis McClinton, Willie Davis, Jim Shorter, and John Wooten—tasked with determining the sincerity of Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be drafted by the U.S. Army based on his religious views as a Muslim. Several of the group were ex-military and did not look sympathetically on Ali’s stance.

Bill was the most famous member of the summit, other than Jim Brown and Ali, but he never tried to leverage that to influence the rest of us. His approach was logical and dispassionate, encouraging us to listen with open minds to what Ali had to say. That reasonable approach proved to be much more effective than trying to sway us. He knew Ali could speak eloquently and passionately for himself, and that if we were open, we would see the truth in what he said. That was a huge lesson in humility and leadership that guided me for many years after.

The Bill Russell of the Cleveland Summit was who I wanted to be when I grew up. In fact, the Bill Russell of the Cleveland Summit made me grow up right then and there. As I had emulated him on the court, I chose to also emulate him off the court. I read interviews with him and I read his 1966 autobiography Go Up for Glory about his experiences growing up in segregated America and the obstacles he faced as a Black man in America, despite his fame and accomplishments. What especially struck home was his refusal to become the stereotypical Angry Black Man that many tried to force him to be. Instead, he chose to focus on finding a path to change and social justice through specific actions and programs.

Years later when some in the press tried to characterize me as the Angry Black Man, I tried to follow Bill’s rational example to remain calm and join the fight by championing specific solutions rather than just rage and shake my fist. Although, sometimes the frustrations call for a good fist-shaking. Then, as Bill taught me, it’s back to doing the hard work that actually brings change.

Less profound but nonetheless insightful, Harvey Araton for The New York Times (“Bill Russell’s Words Were Worth the Wait“):

It is an indisputable fact that time with Russell was not generously dispensed. When it was, only the most hardheaded among us wasn’t better for it.

I was a terrified young reporter for The New York Post in the late 1970s when my editor ordered me to “get Russell” for an assigned story. I found him in the media dining area at the old Spectrum arena in Philadelphia on a Sunday afternoon before a game he was working as network analyst.

As I hopelessly stammered through my introduction, Russell looked up from a plate of food and said nothing. Seconds felt like hours until Billy Cunningham, the 76ers coach, leaned over and came to my rescue. “He’s from Vecsey’s paper,” Cunningham told Russell, referring to Peter Vecsey, the widely known N.B.A. columnist.

This apparently was a useful reference in what was a far more insular N.B.A. environment. Russell nodded and said, “Wait outside for me.” So I parked myself in the first row of seats behind the broadcast table. Ten minutes became 20, then 30, then 60 after Russell took a seat, donned his headset for microphone checks and shuffled through voluminous game notes and stats.

I was literally sweating, and figuratively steaming. Finally, Russell summoned me, shook my hand and said, “Thank you for waiting and respecting my work.”

Lesson learned: Patience may be the most well-cited virtue, but in the interests of professional achievement, so is preparation.

Fast forward to a September 2007 afternoon in a Westchester County suburb of New York, where Russell was speaking to assembled N.B.A. rookies at the league’s transition program. I listened with fascination as Joakim Noah, a player of French, Swedish and Cameroonian descent, asked Russell if he felt underappreciated in racially polarized Boston despite winning 11 titles in 13 seasons, from 1957 through 1969.

“Quite true,” Russell responded in his gravelly voiced, meditative manner. But he elaborated by relaying advice his father had given him as a youth about people who have “these little red wagons that get pulled around and that it’s got nothing to do with me” — meaning that he should not worry about how other people felt about him.

Afterward, I asked Russell how that answer squared with his outspokenness and activism on matters of race and social justice, including his participation in the so-called 1967 Cleveland summit of prominent Black athletes in support of Muhammad Ali following his refusal to be drafted into the U.S. Army.

He reminded me that he had been invited to address the rookie class at large, and that some of the newcomers were not African American. Some were not even American. Russell’s message had been tailored to universal temptation.

“I tell all the kids — rich, poor, Black, white — that you must be your own counsel,” he told me. “We understand that we don’t always want to do the right thing, but what they have to ask themselves is, ‘Am I willing to deal with the consequences?'”

Also the Times, Tania Ganguli (“Bill Russell’s Legacy, and Laugh, Touched Millions“):

It was a day to celebrate Elgin Baylor, whom the Los Angeles Lakers had just honored with a statue outside their home arena. On that warm evening in April 2018, one of Baylor’s greatest antagonists showed up and sat prominently in the crowd.

Bill Russell would never blend in anywhere, and certainly not in his green polo shirt at a Lakers event.

Jerry West, Baylor’s teammate all those years ago, stood behind a lectern and couldn’t help but note Russell’s attendance.

“All the losses to this gentleman over here,” West said. “I forget your damn name. What is it? Bill? Last name — Bill Russell, is that it?”

The crowd loved the bit, and West continued.

“There’s more incredible stories in a losing locker room — and particularly when it’s the same damn team and this smiling jackass over here.”

A few feet away, Russell was indeed smiling, widely. He laughed throughout West’s performance. Russell led the Boston Celtics to 11 championships, seven of them with N.B.A. finals wins over the Lakers — and all of them colored in Celtics green.

West played on six of those Lakers teams that lost to Russell’s Celtics, and the two became friends later in life. He made sure the assembled guests that day didn’t confuse his playful jabs for actual animus, telling them he loved Russell.

It was a bit of a role reversal for Russell, who in his later years was usually the one delivering zingers. Deeply respected for what he did on the court and off it, his jabs were always met with laughter, and in the moments when he was sincere, his earnestness was met with profound gratitude from players for whom Russell changed the N.B.A.

Dying at 88 isn’t a tragedy; you’re well into borrowed time at that point. Russell was born almost a decade before my parents and outlived them both.

Russell was toward the end of his legendary playing career when I was born and I only vaguely remember his time as a game commentator and his lackluster coaching career. (He was more famously a player-coach for the Celtics but was far less successful when he didn’t have himself at center.) But it seems like he has always been an icon.

Time is a funny thing in that way. I’ve always known that he, Ali, Jabbar, and others had been controversial figures way back in the 1960s. But, even though I was alive for the tail end of that period, it’s not part of my lived experience and the television accounts of it are all in black-and-white, making it part of a distant era. At the same time, I’m old enough that things that happened thirty years ago are part of my adult memory and thus seem relatively recent.

Regardless, all of them lived long enough to be revered figures for much of their adult lives. Indeed, all three were awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest recognition our country has for citizenship.

Our family went to see the Celts late in Russell’s career. At that time he was the player-coach and a huge figure in the community. At the time, I didn’t realize it, but Russell has been more important for his civil rights work that he was for his basketball accomplishments.

Farewell and Good Speed.

Great player, even greater man.

His daughter recounted, some time ago, the racism he and his family faced.

https://www.newsweek.com/bill-russell-daughter-account-racism-he-faced-nba-1729491

This may well be the only “famous person” story in my repertoire, but Bill Russell and I happened to both live on Mercer Island at the same time (no, we didn’t travel in the same circles). I was having breakfast at the Perkins’ restaurant probably on a Saturday, but I can’t remember for sure, when he and his wife were seated at a table near mine. No one other than the server ever stopped by their table to talk while they were there. (Not a basketball fan, didn’t even occur to me to.)

I read in an interview in the Times sometime later (maybe before) that he’d chosen Mercer Island as his Seattle area residence because he’d been told that it was a place where he would be able to be anonymous and live his life in relative privacy. Seems that was the case.

Bill Simmons, who managed to score not only an interview but the friendship of Bill at his house on Mercer Island, has a wonderful podcast on that two days he spent with Bill not long ago. There’s a podcast within this article that delves into how and why Bill Russell was Bill Russell.

In me it brought to mind some of the things Bill wrote the “Old Man”, his grandfather, taught him, mostly by example. After hearing Bill Simmon’s words I can recall one of the things and in a different light, as a metaphor for how Bill Russell learned that leadership style.

Russell described his grandfather as a dirt-poor sharecropper who was knowns as a physically exceptionally strong man of few but always meaningful words, and a man who had a magic touch with even the most stubborn mules. Everybody remarked how mules would work harder for him than they would for anyone else. There was no deep description of how he managed to do it, just a comment from the Old Man that if his the mules let him down he would be sad….and they were a team…so they didn’t want him to feel sad…so they bust their tails for him.

That was incomprensible without the context from the podcast linked above, it certainly was for me anyway when I read it in the book. In the context is the story of Bob Cousy breaking down in uncontrollable sobs after losing a playoff and saying the worst thing about it was he had let Bill down it does. The mystery is still there but now I know what Bill was trying to relate when he included it in his autobiography.

Bill was a great player, but not one who will ever be cited along with LBJ or Jordan or Koby as the GOAT player. He was, however, in a class all by himself as a team leader and a mentor.

I was a Celtics fan during those glory years. There is a Russell autobiography that I read in those days. He, and others, dramatically changed basketball. The two handed set shot disappeared, and the jump shot came to dominate. When Russell was at USF winning NCAA championships, the Dons featured the daring innovation of having three black guys on the court at the same time. Maybe there is a point here. Is it possible to imagine American life without Black people? Basketball and other sports would be different. Music would be very different. The rhythm of our hearts would be different. Russell’s grandfather was a share cropper; Bill Russell was a link from his share cropper grandfather to Obama.