Changes To U.S. Hostage Policies Are Less Than Meets The Eye

The Administration announced changes to the way the government handles hostage situations, but it really doesn't amount to much.

Yesterday, President Obama announced changes in how the United States handles hostage situations in foreign countries, and while there has been much commentary about how the changes amount to a major change it seems apparent that much of what’s announced is more a change in public relations than traditional American policy toward hostage taking:

WASHINGTON — President Obama said Wednesday that his administration had too often failed the families of American hostages held overseas by groups like the Islamic State, announcing a policy overhaul that will publicly state for the first time that the United States government can communicate and negotiate with hostage takers.

Mr. Obama said the government would not change a longstanding policy against paying ransoms to terrorist groups, a stance that he acknowledged had become controversial as terrorist threats have evolved and kidnappings have become more common. But he said he was making clear that the rule “does not prevent communication with hostage takers by our government, the families of hostages or third parties who help these families.”

“We’re not going to abandon you,” the president said. “We will stand by you.”

Speaking in the Roosevelt Room of the White House shortly after signing a presidential directive and executive order laying out the changes in the hostage policy, Mr. Obama also said families should not be threatened with criminal charges if they try to pay ransoms.

“The last thing that we should ever do is to add to a family’s pain with threats like that,” the president said, shortly after meeting with former hostages and families of captives, some of whom were killed by the hostage takers.

The changes were an effort by Mr. Obama to come to terms with a brutally painful chapter of his presidency. Families of Americans taken hostage abroad have increasingly criticized his administration for its handling of their cases, saying they were deprived of information, given conflicting guidance, ignored and threatened by a confusing patchwork of government agencies, none of which seemed to be primarily concerned with bringing home their loved ones.

“I acknowledged to them in private what I want to say publicly, that it is true that there have been times where our government, regardless of good intentions, has let them down,” Mr. Obama said. “I promised them that we can do better.”

But in doing so, the president put forth a somewhat tortured logic for addressing hostage cases. He argued forcefully that offering money in exchange for hostages would only enrich terrorists and endanger Americans, but said the government would back family members who wanted to do so.

Top White House officials have been at pains to explain how the government could keep a no-concessions policy while essentially blessing decisions by families to violate it.

“These are very hard issues,” Lisa Monaco, Mr. Obama’s counterterrorism adviser, said in an interview. She said the White House was “wrestling with not abandoning families while also being quite clear that the vast resources of the United States government are not going to be put towards fueling terrorist activities.”

(…)

The policy directive made official and public what has long been the United States government’s unspoken practice in some hostage cases. But that practice has been inconsistently applied and poorly understood both inside federal agencies and among family members desperate to win the release of their relatives.

Mr. Obama’s orders reorganized the government’s hostage recovery efforts, creating an interdepartmental “fusion cell” based at the F.B.I. with primary responsibility for freeing American captives. A new hostage response group at the National Security Council, to be led by Ms. Monaco, will monitor the efforts and oversee hostage policy. A family engagement coordinator will work with the F.B.I. task force and the White House team to support hostages’ relatives.

The order also requires that the government declassify as much information as possible to share with hostages’ families.

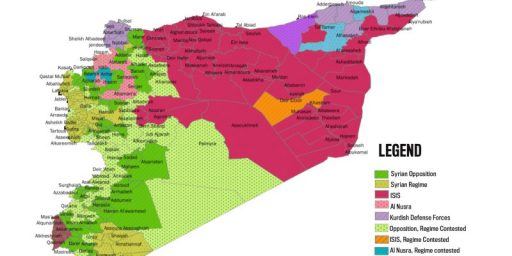

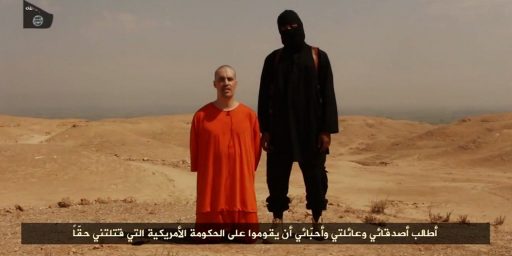

There was some criticism leveled yesterday that the Administration was essentially moving toward a policy that has been followed by some European and other nations in response to the kidnapping of their own citizens by ISIS and related groups in the Middle East and authorizing negotiation with hostages and payment of ransom. That doesn’t seem to be anywhere close where the President is announcing here, though. Instead, most of the policy changes that were announced yesterday seem to be directed more toward the way the government interacts with the families of the people being held hostage than anything else. For example, last year after several Americans being held hostage by ISIS were brutally executed in propaganda videos, reports began to emerge that at least some of the families had been warned by Federal officials that they would be prosecuted if they attempted to negotiate with the people holding their loved ones hostage. While it is true that it is against the law for private citizens to negotiate with groups like ISIS, or to pay them anything resembling a ransom, this threats always seemed rather hollow to me. First of all, it seems unlikely that the Justice Department would want to deal with the public relations nightmare that would be involved in arresting and charge the family members of an American being held overseas, especially after that American had been executed in such a public manner. Second, even if such a person were charged and their case went to trial I don’t know that any jury in the country would be willing to do convict them for doing something that any one of us would have been tempted to do, which would be to do anything possible to bring their loved one home. The announcement that these families would not be prosecuted under those circumstances, then, is just a recognition of reality. Similarly, the goal of improving communication between government officials and the family members of hostages is clearly designed to address the public relations disasters created last year when several family members went public with complaints about the lack of communication from government officials about what was going on with their family members, In one notable case, for example, family members found out that their loved one had died from a reporter who called looking for a comment rather than their supposed contact in the State Department. Improving that process would relieve the government of the embarrassment that such situations create, and is simply the humane thing to do.

As I noted, there have been criticisms of the announcement yesterday that alleged that the Administration’s announced changes in policy essentially amount to a change in “long standing policy” against negotiating with terrorists. Notwithstanding the fact that this just doesn’t seem to true at all when you look at the substance what was announced, the criticism itself ignores reality and history. The statement that America “does not negotiate with terrorists” is something that has been repeated for decades now as a signal that the United States was taking a “get tough” approach to terrorism. In some ways, it’s a position that makes sense because the impression that any nation will almost always give terrorists holding their citizens hostage whatever they want in the name of safety seems designed to just encourage further kidnappings. Even while were making that statement publicly, though, the United States has in fact negotiated with terrorists in the past, and will continue to do so in the future. The most famous example, of course, was during the Reagan Administration when the efforts to negotiate with Hezbollah and other terrorists via their Iranian sponsors for the release of the Americans and other Westerners being held in Lebanon became so much of a policy obsession inside the White House that it led to a major political scandal. Prior to the Reagan Administration, we negotiated with hostage takes to get the hostages being held in the U.S. Embassy in Tehran released. Outside of Iran-Contra and the Iranian Hostage Crisis, there have been many other examples of the United States “negotiating with terrorists” that make it clear that this public stance is not a reflection of reality.

The biggest question, of course, is whether any of the changes announced yesterday would lead to changes in how ISIS approaches kidnappings. Given the fact that this group in particular seems to be interested in kidnapping for reasons that have little to do with how much money they can get in return for the hostages they’re holding, the answer would seem to be no. Hostages are valuable to ISIS in the manner in which they can be used a propaganda tools, recruitment tools, and ways to shock the West. When ISIS has made ransom demands they amounts have been so utterly absurd that it’s clear that they aren’t really being serious. Given that, it seems unlikely that these policy changes will actually change much of anything. There have been improvements made in the way the government interacts with families of hostages that seem sensible, and the idea of creating a centralized working group to deal with hostage situations seems advisable. Beyond that, though, this mostly seems like window dressing.