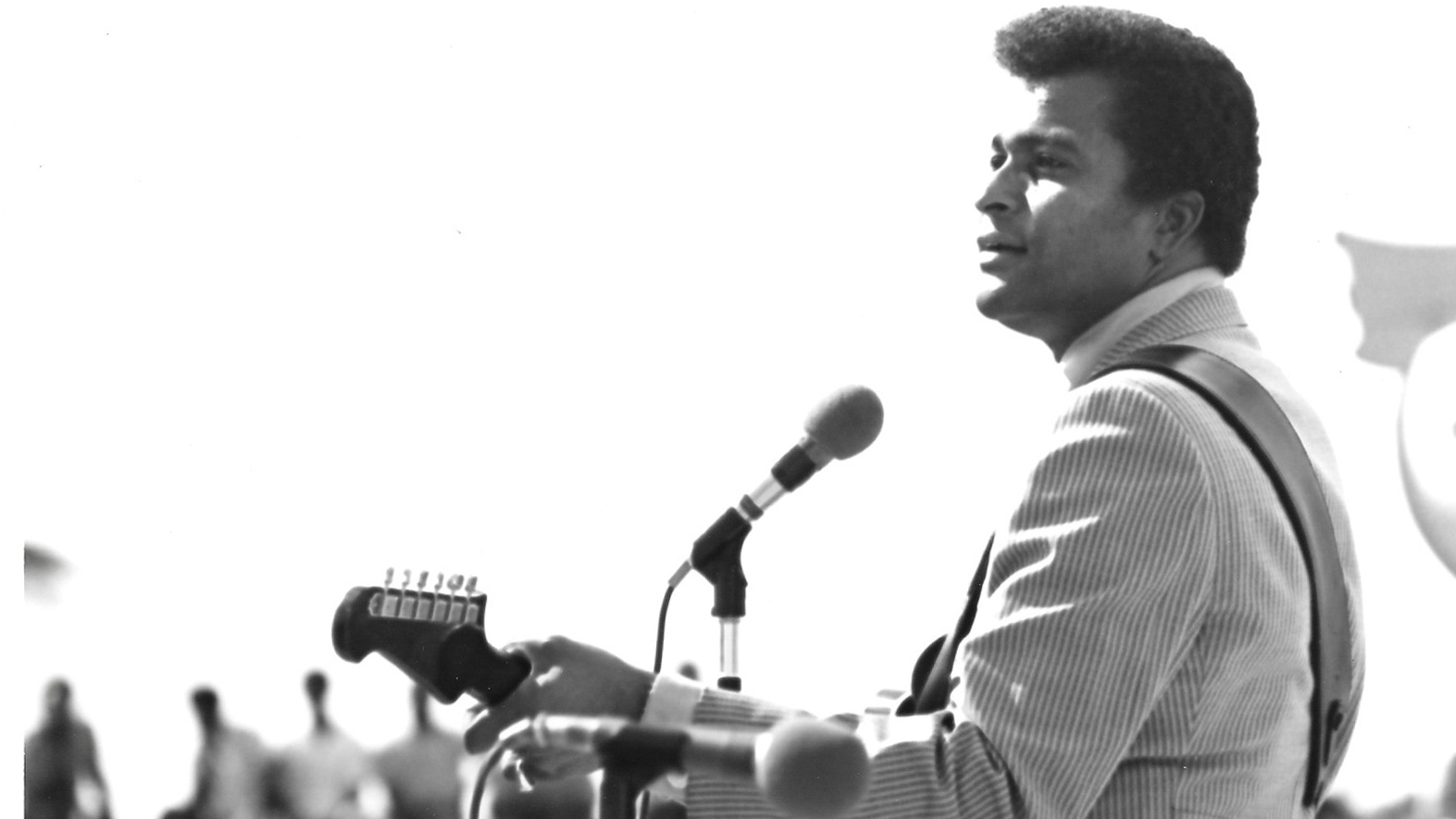

Charley Pride Dead at 87

A country music legend is yet another victim of COVID.

Charley Pride’s voice was unique and produced a string of country hits in four separate decades. But he’s best known for what he looked like.

NPR (“Charley Pride, Country Music’s First Major Black Star, Dies At 86“):

Charley Pride, who sold millions of records and was the first Black performer to become a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, among many other honors, has died at age 86. A statement posted on the singer’s website said Pride passed away in Dallas, Texas, on Saturday from complications due to COVID-19.

A sharecropper’s son from Mississippi, Pride became one of the first Black men to become a major star in genre where most of the biggest hitmakers are white. Rising to prominence in the 1960s and ’70s, Pride recorded dozens of songs that topped the country music charts, including “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin'” and “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone.”

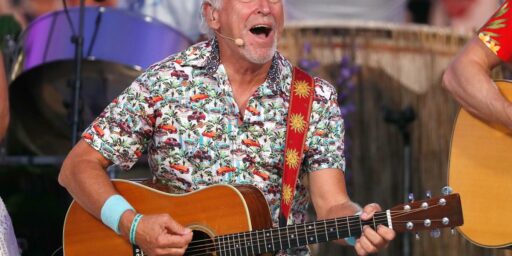

Pride had at least 30 no. 1 hits on the country music charts, and won nearly every major award in available to a country musician. In all, Pride won three Grammys, including “Best Male Country Vocal Performance” in 1972 as well as several awards from the Country Music Association, who named him their Entertainer of the Year in 1971. His final performance was on November 11 at the CMA Awards, where he performed “Kiss and Angel Good Mornin'” with Jimmie Allen.

Alongside his competitive accolades, Pride gained nearly every other honor awarded to someone of his stature in the genre, including inductions into the Country Music Hall of Fame, in 2000, and the Grand Ole Opry — the mecca of country music where Pride first performed in 1967 — in 1993.

Pride’s accomplishments weren’t just confined to the Nashville scene. Honors came from as far away as Hollywood, including a star on the Walk of Fame in 1999 and a lifetime achievement from the Grammy awards in 2017. He also reportedly served as the inspiration for the character Tommy Brown – a fictional Black country music performer played by the actor Timothy Brown – in Robert Altman’s sprawling 1975 film Nashville.

Just before he received the Lifetime Achievement Grammy, he told NPR he often resisted the label of pioneer.

“I’ve never seen anything but the staunch American Charley Pride,” he says. “When I got into it, they used different descriptions. They’ll say, ‘Charley, how did it feel to be the Jackie Robinson of country music?’ or ‘How did it feel to be first colored country singer?’ Pride said.

“It don’t bother me, other than I have to explain it to you — how I maneuvered around all these obstacles to get to where I am today. I’ve got a great-grandson and daughter, and they’re gonna be asking them that too if we don’t get out of this crutch we all been in all these years of trying to get free of all that, you see? ‘Y’all,’ ‘them’ and ‘us.'”

AP (“Charley Pride, a country music Black superstar, dies at 86“):

Charley Pride, one of country music’s first Black superstar whose rich baritone on such hits as “Kiss an Angel Good Morning” helped sell millions of records and made him the first Black member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, has died. He was 86.

[…]

Pride released dozens of albums and sold more than 25 million records during a career that began in the mid-1960s. Hits besides “Kiss an Angel Good Morning” in 1971 included “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone,” “Burgers and Fries,” “Mountain of Love,” and “Someone Loves You Honey.”

He had three Grammy Awards, more than 30 No. 1 hits between 1969 and 1984, won the Country Music Association’s Top Male Vocalist and Entertainer of the Year awards in 1972 and was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000. He won the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award last month by the Country Music Association.

“He destroyed barriers and did things that no one had ever done,” said Darius Rucker on Twitter. “Heaven just got one of the finest people I know.” Tanya Tucker tweeted “I’m just so thankful I got to sing a song with him.” Billy Ray Cyrus called him a “gentleman,” “legend” and a “true trailblazer.”

The Smithsonian in Washington acquired memorabilia from Pride, including a pair of boots and one of his guitars, for the the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Ronnie Milsap called him a “pioneer” and said that without his encouragement, Milsap might never gone to Nashville. “To hear this news tears out a piece of my heart,” he said in a statement.

Other Black country stars came before Pride, namely DeFord Bailey, who was an Grand Ole Opry member between 1927 and 1941. But until the early 1990s, when Cleve Francis came along, Pride was the only Black country singer signed to a major label. In 1993, he joined the Opry cast in Nashville.

“They used to ask me how it feels to be the `first colored country singer,'” he told The Dallas Morning News in 1992. “Then it was `first Negro country singer;’ then `first black country singer.- Now I’m the `first African-American country singer.- That’s about the only thing that’s changed. This country is so race-conscious, so ate-up with colors and pigments. I call it `skin hangups’ — it’s a disease.”

[…]

In 2008 while accepting a Lifetime Achievement Award as part of the Mississippi Governor’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts, Pride said he never focused on race.

“My older sister one time said, ‘Why are you singing THEIR music?'” Pride said. “But we all understand what the y’all-and-us-syndrome has been. See, I never as an individual accepted that, and I truly believe that’s why I am where I am today.”

As a young man before launching his singing career, he was a pitcher and outfielder in the Negro American League with the Memphis Red Sox and in the Pioneer League in Montana.

[…]

After a tryout with the New York Mets, Pride visited Nashville and broke into country music when Chet Atkins, head of RCA Records, heard two of his demo tapes and signed him.

To ensure that Pride was judged on his music and not his race, his first few singles were sent to radio stations without a publicity photo. After his identity became known, a few country radio stations refused to play his music.

For the most part, though, Pride said he was well received. Early in his career, he would put white audiences at ease when he joked about his “permanent tan.”

“Music is the greatest communicator on the planet Earth,” he said in 1992. “Once people heard the sincerity in my voice and heard me project and watched my delivery, it just dissipated any apprehension or bad feeling they might have had.”

NYT (“Charley Pride, Country Music’s First Black Superstar, Dies at 86“):

Charley Pride, a son of sharecroppers who rose to become country music’s first Black superstar on the strength of hits including “Kiss an Angel Good Mornin'” and “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone,” died on Saturday in hospice care in Dallas. He was 86.

[…]

Mr. Pride was not the first Black artist to record country music, but none of his predecessors had anywhere near the degree of success he enjoyed. In 1971, just four years after his first hit records, he won the Country Music Association’s entertainer of the year award — the genre’s highest honor.

[…]

Mr. Pride — who grew up listening to Grand Ole Opry concerts on the radio — was discovered in a bar in Montana, singing Hank Williams’s “Lovesick Blues.”

He began his recording career in 1963; two years later, he signed a contract with RCA Records, shuffling between Montana and Nashville before eventually relocating live full time in the hub of country music.

In 1967, his recording of “Just Between You and Me” became a Top 10 hit on Billboard’s country music charts. Only then did he quit his smelting job.

Watching the outpouring of praise from fellow country legends on Twitter yesterday afternoon, it struck me how natural it seemed even though country music is still an overwhelmingly white genre. But he really has been embraced by the industry throughout. The NYT story buries an anecdote that I don’t recall having seen before even though I likely witnessed it on television at the time:

Though Mr. Pride faced racism in the industry — the singer Loretta Lynn was instructed not to embrace him at an awards show in the 1970s should he win the award she was presenting — many of his white counterparts in country music welcomed him as the star he had become. (He did win the award, and Ms. Lynn not only hugged but kissed him.)

When word spread that Mr. Pride was Black, many radio stations refused to play his music. But Faron Young, a white country music star, came to Mr. Pride’s defense, telling one station manager that “if he takes Charley Pride off, take all my records off.”

Dolly Parton said on Saturday she was “heartbroken that one of my dearest and oldest friends, Charley Pride, has passed away.”

“It’s even worse to know that he passed away from COVID-19,” she added on Twitter. “What a horrible, horrible virus.”

Former President George W. Bush remembered Mr. Pride as “a fine gentleman with a great voice,” saying in a statement: “Laura and I love his music and the spirit behind it.”

The Nashville Tennessean (“Charley Pride, country music’s first Black superstar, dies at 86 of COVID-19 complications“):

Charley Pride — a sharecropper’s son who rose from rural Mississippi to become the first Black superstar in country music — died Saturday at age 86.

The “Kiss An Angel Good Mornin” singer died in Dallas, Texas, due to complications from COVID-19, according to a news release from his publicist, Jeremy Westby.

In a career spanning more than five decades, Pride cemented a trailblazing legacy unlike any entertainer before him.

He overcame club audiences unwilling to hear a Black singer cover Hank Williams and promoters equally skeptical at hosting his performances to once being the best-selling artist on RCA Records since Elvis Presley.

Pride topped country charts 29 times in his career, singing stories rich with honesty — “I Can’t Believe That You’ve Stopped Loving Me,” “I’m Just Me” and “Where Do I Put Her Memory,” among others — in his distinct, welcoming baritone voice.

[…]

In the 1950s, not a decade after Jackie Robinson smashed segregation barriers for Black athletes in the major leagues, Pride would peruse his own major league career. He bounced between Negro leagues and major league farm systems, pitching for teams in Wisconsin, Kentucky, Alabama, Idaho, Texas and, perhaps most notably, the Memphis Red Sox.

He’d earn a stop in 1956 on the Negro American League all-star team, only to be drafted later that year into U.S. military service. He served until 1958.

“I was gonna go to the major leagues and break all the records there and set new ones,” Pride said, adding a laugh. “By the time I was 35 or 36, then I was gonna go sing. That’s what my plan was.”

There has been speculation on Twitter that Pride contracted COVID at the CMA presentation last month—the first show of its kind to be conducted in-person since the pandemic’s outbreak—but the family denies it and the organization has outlined the strictness of the protocols Pride and other attendees were subject to.

Pride’s career as a professional singer began the same year I was born, so I literally don’t remember a time before his music. While racism was very much a thing in both America and my household at the time, his records (and later those of Mexican-American Freddy Fender) were nonetheless on heavy rotation. Musicians, athletes, and other entertainers often manage to transcend race.

Just as I started school in Houston, Texas in 1972 blissfully unaware that the schools there had just begun to seriously desegregate two years earlier, I was only marginally aware how big a deal Pride’s status was and had no idea what he endured to get there. But, even by the time I was seeing him make appearances on the various variety shows of the day, he or the host would always make a joke about his not looking like the other country artists.

While he had released some other singles that would later be popular, his breakout hit was 1966’s “Just Between You and Me”:

1970’s “Is Anybody Going to San Antone” is among his first #1s:

And, of course, 1971’s “Kiss An Angel Good Mornin'” became his signature song:

PBS’ American Masters series devoted a 53-minute episode to him last February titled “Charley Pride: I’m Just Me.” It’s available for streaming at the link at least through December 26.

Pride was also heavily featured in Ken Burns’ “Country Music” documentary, and an 11-minute excerpt, “Charley Pride and Civil Rights,” is available online.

I started school in the Fall of 1974 and only recently found out that Mississippi started really desegregating in 1970. It blew me away.

I thought Alabama had been the only other hold out. I guess Texas was with them too.

@Robert Prather: We have an unfortunate tendency, especially in the primary and secondary schools, to teach history as a series of dates. So, boom, schools were desegrated with Brown v BOE in 1954 and it took place instantaneously. Not so much!

Yeah, indeed. I knew that Eisenhower sent troops to Little Rock, but I thought it had all been taken care of long before 1970. Live and learn.

The apparent whiteness of country is even more insidious than many people realize. There is in fact a close historical relationship between country and “black” genres such as blues and jazz, and many of the most formative country artists took significant influence from black musicians. The genre categories themselves were defined so as to draw boundaries around black music, and there’s a long history of those categories being used as coded ways of trying to exclude black musicians. (You saw this even in the early days of MTV, when black artists such as Michael Jackson were initially not played because they were labeled “R&B”–which itself evolved from a genre that was once literally termed “race music.”) Even if the country-music community today is not intrinsically racist (though I think there’s an element of that, when you consider the right-wing politics that’s so pervasive among these folks), the whiteness isn’t just some artifact of cultural tendencies, it’s rooted deeply in the history.