China’s Worrisome Behavior

The competition is slowly ratcheting up.

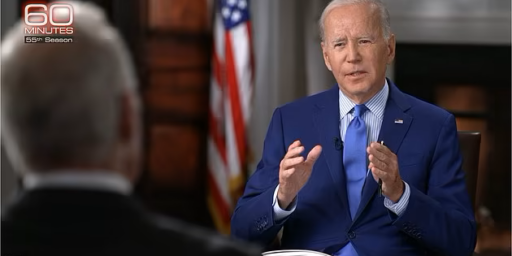

As noted yesterday, the Biden Administration has followed its two predecessors in increasingly focusing on “strategic competition” with a rising China as the centerpiece of its national security strategy. Three reports in today’s papers highlight the state of affairs.

NYT (“U.S. Officials Grow More Concerned About Potential Action by China on Taiwan“):

The Biden administration has grown increasingly anxious this summer about China’s statements and actions regarding Taiwan, with some officials fearing that Chinese leaders might try to move against the self-governing island over the next year and a half — perhaps by trying to cut off access to all or part of the Taiwan Strait, through which U.S. naval ships regularly pass.

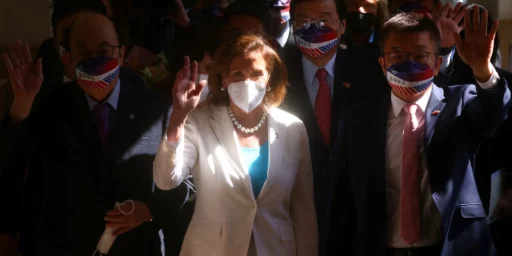

The internal worries have sharpened in recent days, as the administration quietly works to try to dissuade House Speaker Nancy Pelosi from going through with a proposed visit to Taiwan next month, U.S. officials say. Ms. Pelosi, Democrat of California, would be the first speaker to visit Taiwan since 1997, and the Chinese government has repeatedly denounced her reported plans and threatened retaliation.

U.S. officials see a greater risk of conflict and miscalculation over Ms. Pelosi’s trip as President Xi Jinping of China and other Communist Party leaders prepare in the coming weeks for an important political meeting in which Mr. Xi is expected to extend his rule.

Chinese officials have strongly asserted this summer that no part of the Taiwan Strait can be considered international waters, contrary to the views of the United States and other nations. A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman said in June that “China has sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the Taiwan Strait.”

American officials do not know whether China plans to enforce that claim. But Senator Chris Coons of Delaware, who is close to President Biden and deals with the administration often on issues involving Taiwan, said “there is a lot of attention being paid” to what lessons China, its military and Mr. Xi might be learning from events in Ukraine.

“And one school of thought is that the lesson is ‘go early and go strong’ before there is time to strengthen Taiwan’s defenses,” Mr. Coons said in an interview on Sunday. “And we may be heading to an earlier confrontation — more a squeeze than an invasion — than we thought.”

This is difficult to assess but obviously concerning. For the last two decades or so, I’ve argued that it’s hard to conjure a plausible scenario for a US-China shooting war, given the enormous toll it would take and the degree of economic interdependence between the two. The exception, though, was always Taiwan. While most Western analysts, myself certainly included, since the “One China” policy as a legal fiction, a fig leaf to allow China to save face despite the reality that Taiwan is a separate, independent state, Beijing decidedly does not see it that way. It’s an existential issue for them: Taiwan is part and parcel of China and, while they have a large degree of autonomy, allowing them to be recognized as a sovereign nation would be shameful and catastrophic.

Certainly, Beijing’s rhetoric on this issue has ratcheted up as its military power has grown. But even experts on Chinese military policy, including my Marine Corps University colleague Chris Yung, have strong disagreements on where the red line is. I simply have no idea how perilous this situation is.

WSJ (“China Targeted Fed to Build Informant Network, Access Data, a Probe Says“):

China tried to build a network of informants inside the Federal Reserve system, at one point threatening to imprison a Fed economist during a trip to Shanghai unless he agreed to provide nonpublic economic data, a congressional investigation found.

The investigation by Republican staff members of the Senate’s Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs found that over a decade Fed employees were offered contracts with Chinese talent recruitment programs, which often include cash payments, and asked to provide information on the U.S. economy, interest rate changes and policies, according to a report of the findings released on Tuesday.

In the case of the economist, the report said, Chinese officials in 2019 detained and tried to coerce him to share data and information on U.S. government policies, including on tariffs while the U.S. and China were in the midst of a trade war.

The report doesn’t say whether any sensitive information was compromised. Access to such information could provide valuable insights given the Fed’s extensive analysis of U.S. economic activity, its oversight of the U.S. financial system, and the setting of interest-rate policy.

This is worrisome but at a much lower level. Countries spy on one another all the time and it’s hardly a surprise that the Chinese government is trying to recruit sources within our government. The Fed is an obvious place where they would like more insight. Presumably, we’re trying to do the same sort of thing in China. It’s just that, because our society is so open and theirs is not, they have an easier job on this front.

The only piece of this that’s outside the normal rules of the game is the threats of imprisonment as a tool for solicitation. I would expect to see some high-level response to this. Certainly, we should further limit the travel of non-diplomatic personnel to China for the foreseeable future.

NYT (“Where China Is Changing Its Diplomatic Ways (at Least a Little)“):

Whirlwind visits to crisis-riven nations in Africa. A sleek training center for the continent’s up-and-coming politicians. The prospect of major debt forgiveness for a favorite African country.

As relations with the United States and Europe plummet, China is starting a new wave of diplomacy in Africa, where it dominates trade with resource-rich nations and keeps friendly ties with mostly authoritarian leaders, unfettered by competition from the West.

China’s campaign to cultivate African allegiances is part of a great geopolitical competition, which has intensified since the start of the war in Ukraine. Already fiercely vying for loyalties in Asia, Beijing and Washington are now jockeying broadly for influence, with the United States, Europe and their democratic allies positioned against China, Russia, Iran and other autocracies. Heightening the competition, Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey V. Lavrov, began a tour of Egypt, Ethiopia, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo Sunday.

In Africa, China is adjusting its approach, more closely integrating financial and diplomatic efforts. It’s a recognition that just building new expressways, hydropower dams and skyscrapers — as China has tried to do with the Belt and Road Initiative — isn’t sufficient to secure relations.

While the initiative across dozens of countries has helped to relegate the United States to a second-tier position in many places, the projects have also amplified tensions and added to a mounting debt crisis. To complement the rails and roads, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, started a new Global Security Initiative in the spring, a broad effort to bring developing countries together.

A big lender to Africa, Beijing is seeking to protect current and future assets, including demand for the continent’s vast minerals. It also wants to make sure its first overseas naval base, in Djibouti at the entrance of the Red Sea, operates smoothly to ensure shipments of oil.

This, by contrast, is simply China acting as we would expect a rising power to act. They are absolutely allowed to compete for influence in the world. They have significant advantages over us in gaining these sorts of footholds in Africa because they are not hamstrung by ethical rules that prevent bribing officials and providing certain kinds of technology to countries with dubious human rights records. But we also have an advantage, in that these rules—and our broader strategic culture—also prevent us from imposing the draconian terms the Chinese do for inability to pay off loans on time, essentially forcing countries to cede ports and other key terrain.

As Dan Nexon and others have been arguing for a while, there is some danger in the “great power competition”* lens turning everything into a fight.

Treating it as a guiding principle of American grand strategy risks confusing means and ends, wasting limited resources on illusory threats, and undermining cooperation on immediate security challenges, such as climate change and nuclear nonproliferation. In the long run, a fixation on great-power competition is likely to undermine, rather than enhance, U.S. power and influence.

The Eurasia Group’s Ali Wyne has a new book out on this subject and is interviewed by WaPo’s Ishaan Tharoor.

His new book — “America’s Great-Power Opportunity: Revitalizing U.S. Foreign Policy to Meet the Challenges of Strategic Competition” — makes the case that while “interstate competition is a characteristic of world affairs,” it does not need to become “a blueprint for foreign policy.” Indeed, when you let anti-Chinese or anti-Russian agendas drive your own, it gives these putative adversaries outsize influence over your own decision-making, he argues.

[…]

The traction that great power competition has come to achieve as a policymaking framework reflects a paradoxical combination: strategic anxiety on the one hand, bureaucratic comfort on the other.

The United States is not as relatively preeminent as it was at the end of the Cold War — or even at the turn of the century — and China and Russia are increasingly able and willing to contest its influence. On the other hand, the existence of formidable challengers would seem to furnish the strategic clarity for which Washington has been searching since the Soviet Union’s collapse; it would also, importantly, seem to require a familiar playbook.

For roughly half a century, after all, U.S. foreign policy was largely oriented around dealing with external competitors: imperial Japan, Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union. The trouble is that that stretch of history primed the United States to expect decisive victories: Japan and Germany suffered military defeats, and the Soviet Union experienced a dramatic disintegration.

It seems unlikely, however, that China and Russia will collapse, notwithstanding their myriad socioeconomic challenges and strategic constraints, so America’s task will be to forge ambiguous and uncomfortable cohabitations.

There’s a lot more there but you get the point.

_________________

*”Great power competition” was the preferred phrase of the Trump administration, particularly its first Secretary of Defense, Jim Mattis. The Biden administration renamed it “strategic competition” because, well, they wanted to put their own branding on it. Most of the natsec community still uses GPC.

Something that isn’t formally written down (AFIK) but is nonetheless Chinese policy: if you are of reasonably racially pure Chinese ethnicity, the Chinese government considers you one of “theirs” no matter where you live and how long your family has been there. They demand you put China’s interests ahead of your own country’s. This is one of the reasons Australia’s relations with China has soured.

China has a demographic problem, and a worker productivity problem, and a bankrupt housing market problem, and a banking problem, and problems created by wolf warrior diplomacy, and more problems created by giving huge loans to countries, like Congo, that have no chance of paying loans back but don’t have any strategic ports to offer up. Xi may decide he needs a war to distract from his many failures.

China cannot invade Taiwan. It has nowhere near the sea or airlift capacity to move a quarter million troops a hundred miles and support them. D-Day was pulled off in an age before satellites, but any Chinese attempt to cross the strait will have been clearly visible to the whole world for weeks or months ahead of time. And while China has a large military and increasingly sophisticated weapons, they have not fought a war since 1979 which they managed to lose to Vietnam. (Join the club.) Previous to that it was human wave assaults in Korea – and they lost there, too. Can the Chinese keep our aircraft carriers out of the strait? Yep. Can they keep American submarines from sinking their ships? Nope.

What the Chinese can do is lob missiles at Taiwan, hoping to bring it to its knees. That’s not hard to do. You don’t need a well-trained military for that. But can Xi survive if the world imposes sanctions? Russia is a net exporter of food and energy, China is the opposite. Would Xi survive worsening economic conditions, maybe even famine, in China?

One big question is Taiwan’s Foxconn – China needs those semiconductors as much as we do. Will Xi cut off his nose to spite his face?

It’d be stupid for Xi to attack Taiwan. But Xi is no more a strategic genius than Putin. Overreach and authoritarianism go hand in hand.

My objection to these kinds of analyses/conclusions is that they always seem to ignore or downplay the fact that China and Russia get a say in how our relationships play out, and they clearly do see them through a “great power competition” lens. These commentators like to point out that we don’t have the power to unilaterally set the agenda in world affairs anymore, but ironically, their analyses always seem to proceed from the assumption that we do, in fact, get to unilaterally decide what our relationship with China and Russia will be.

The other thing China can do is declare a maritime blockade of Taiwan and then dare the US to run it. Basically a replay of the Cuban Missile Crisis with us on the other side of the table.

@R. Dave:

Very astute point. The enemy gets a vote.

@R. Dave:

I was just looking to see whether Taiwan has ports on the Pacific side. Looks thin. And the other transport links to their east coast look sparse across mountain ranges. Yeah, that’s not good. We can keep the Chinese Navy off their east coast, not so much their west coast.

@Michael Reynolds:

The answer to that is simple. Almost all of Foxconn’s production capacity is on the Mainland. Xi can just confiscate them.

I don’t understand what this means:

Why just staff Republicans? Is this normal? Was this under the Trump Admin? While the Senate was majority R?

Also, does that mean the FBI didn’t catch this? It’s their job, after all.

@Michael Reynolds:

@R. Dave:

This is what I’ve been saying. Tell the world the time has come to take the renegade province back. Declare the ports and airports on Taiwan closed. (Might have to sink an LNG tanker or shoot down a cargo jet to make that point.) Demonstrate you can build and fire 500 reasonably smart cruise and/or ballistic missiles per day. Level anything vaguely military, then work your way down most of the economy. “Nationalize” TSMC and very carefully avoid shooting up the fabs. On a humorous note, if the US tries to get involved, offer to recognize Texas or California as independent countries if they want to separate.

@Mu Yixiao:

Foxconn is an assembly company. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is the world-class integrated circuit company. They’re one of three companies in the world — Samsung and Intel the other two — that can build parts using 10nm or better technology. TSMC has been notorious for keeping their leading edge production fabs on Taiwan exclusively.

@Michael Cain:

Correct. And I know that. My screw-up on that one. I was replying to Michael Reynolds, and didn’t think it through.

@Michael Cain:

They can blockade Taiwan, but we can block Chinese ships through the Malacca straits, the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. Depending on how far we are prepared to go, we hold the winning hand.

An interesting opening move from China would be to block US arms shipments to Taiwan. Cuba 2, the Wrath of Xi.

@R. Dave:

Problem with a blockade.

If you are blockading in the waters east of Taiwan, your blockade ships are vulnerable to American SSN operating in deep water.

And your own shipping is vulnerable to a counter-blockade in distant waters.

China needs energy imports for it’s economy to function: imports are 70% of oil use (almost all by ship, not pipe) and even 6% and growing of coal.

It could probably substitute domestic coal for such critical areas as nitrogen fertiliser production.

But overall, loss of hydrocarbon imports would collapse the Chinese economy.

@Michael Cain:

If the Taiwanese are smart they’ll build Hsiung Feng/Sheng cruise missiles (or buy equivalent or better?) sufficient to retaliate in kind.

And one lesson from the war in in Ukraine is that missile bombardment against a determined defender may not work as well as it’s planners may hope.

Especially if Taiwan builds out its SkyBow systems (and the US quietly transfers such technologies as may be required to upgrade them).

The best US course might be to quietly assist Taiwan to become sufficiently strong in its own right to deter an opportunistic attack at a moment of miscalculation.

@Michael Reynolds:

@JohnSF:

At some point in there are actual acts of war against the PRC. I’m willing to make a modest wager — my usual is for a good craft beer — that the US will stop short of those in the event that the PRC declares they are bringing their wayward child back into the fold. We’re not going to stop PRC ships in international water, or straits covered by international law. We’re not going to force our way past a PRC blockade. And if Taiwan ever strikes at the mainland, everyone’s assistance will instantly disappear.

China is going to have to piss or get off the pot—and soon or their window is gone.

We aren’t as ready as we’d like to be but we’re getting there— retooling the Force for a peer-fight. We just need to use diplomacy to kick the can down the road another 4 years and we’ll have the stick we need to knock the hell out of them (if need be of course)

Fun times for our young Service Members coming up

@Michael Cain:

I think we pretty much have to. Lose Taiwan and we lose high-end semiconductors and we let China into the Pacific. Not letting the Chinese Navy escape is a very high priority.

@Michael Cain:

It will depend.

If the United States seriously wishes to preserve the independence of Taiwan, and if China is determined to end that independence, by acts of war, then the US will need to confront bombardment &/or blockade by China with actions of similar violence.

In short, to meet war with war.

If that is the case, then it needs a clear realisation of what such “confrontation”, that is, warfare, entails and risks.

To accept one sided bombardment or blockade is to concede defeat at the outset.

To do otherwise almost inevitably means direct combat engagement with a nuclear Power.

To avoid such a war, there is a case that it is best to deter it.

And that can best be done by making it plain, in advance, that the US is prepared to risk, and fight, a war with China.

If the US is not prepared to engage in such risk, it’s commitment to Taiwan’s independence or autonomy, if that is the preferred term, is effectively void.

If so, it might be better to renounce that commitment now, and advise Taiwan to make and take the best deal it can.

There, though, also be a realisation of what such a decision to avoid the risk of war, entails and endangers.

It would be highly likely, though not inevitably, to entail thee collapse of the US alliance systems in Asia, if the US was prepared to abandon a long-standing protectorate.

It would also place the US Navy in a markedly worse operational position, with the PLAN no longer constrained by the inner island chain.

It would obviously be better to be able to dissuade China from a determination to subordinate Taiwan by means other than counter-threats and military deterrence.

But if there is any such means at hand, it’s not easy to see what on Earth it could be.

So the decision is in the hands of China.

The US pursued a course of peaceful engagement and the integration of China into the Western constructed global systems for decades, despite periodic concerns about it’s breaches of understandings on property rights, human rights, territorial rights etc. etc.

Little good does it seem to have done in the way of establishing a willingness to compromise.

Got to give Speaker Pelosi her due, she usually does not suffer bullies. I would like to see her to visit Taiwan and give this latest version of Chinese warlords a demonstration our resolve for freedom.