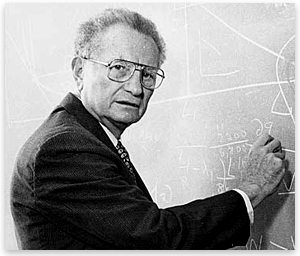

Daniel Kahneman, 1934-2024

The psychologist who won a Nobel in economics is gone at 90.

Washington Post, “Daniel Kahneman, Nobel laureate who upended economics, dies at 90“

Daniel Kahneman, an Israeli American psychologist and best-selling author whose Nobel Prize-winning research upended economics — as well as fields ranging from sports to public health — by demonstrating the extent to which people abandon logic and leap to conclusions, died March 27. He was 90.

His death was confirmed by his stepdaughter Deborah Treisman, fiction editor at the New Yorker. She did not say where or how he died.

Dr. Kahneman’s research was best known for debunking the notion of “homo economicus,” the “economic man” who since the epoch of Adam Smith was considered a rational being who acts out of self-interest. Instead, Dr. Kahneman found, people rely on intellectual shortcuts that often lead to wrongheaded decisions that go against their own best interest.

These misguided decisions occur because humans “are much too influenced by recent events,” Dr. Kahneman once said. “They are much too quick to jump to conclusions under some conditions and, under other conditions, they are much too slow to change.”

Dr. Kahneman was affiliated with Princeton University when he won the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences “for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty.” He shared the award with Vernon L. Smith, then of George Mason University in Virginia, who pioneered the use of laboratory experiments in economics.

Dr. Kahneman took a dim view of people’s ability to think their way through a problem. “Many people are overconfident, prone to place too much faith in their intuitions,” he wrote in his popular 2011 book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow.” “They apparently find cognitive effort at least mildly unpleasant and avoid it as much as possible.”

Dr. Kahneman spent much of his career working alongside psychologist Amos Tversky, who he said deserved much of the credit for their prizewinning work. But Tversky died in 1996, and the Nobel is never awarded posthumously.

Both men were atheist grandsons of Lithuanian rabbis, and both had studied and lectured at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Their three-decade friendship and close collaboration, chronicled in Michael Lewis’s 2016 book, “The Undoing Project,” was a study in opposites.

According to Lewis, Tversky was the life of the party; Dr. Kahneman never even went. Tversky had a mechanical pencil on his desk and nothing else; Dr. Kahneman’s office was full of books and articles he never finished. Still, Dr. Kahneman said, at times it was as if “we were sharing a mind.” They worked so closely together that they tossed a coin to decide whose name would go first on an article or a book.

Their research helped establish the field of behavioral economics, which applies psychological insights to the study of economic decision-making, but also had a far-reaching effect outside the academy. It was credited with changing the way baseball scouts evaluate prospects, governments make public policy and doctors arrive at medical diagnoses.

New York Times, “Daniel Kahneman, Who Plumbed the Psychology of Economics, Dies at 90“

Daniel Kahneman, who never took an economics course but who pioneered a psychologically based branch of that field that led to a Nobel in economic science in 2002, died on Wednesday. He was 90.

[…]

Professor Kahneman, who was long associated with Princeton University and lived in Manhattan, employed his training as a psychologist to advance what came to be called behavioral economics. The work, done largely in the 1970s, led to a rethinking of issues as far-flung as medical malpractice, international political negotiations and the evaluation of baseball talent, all of which he analyzed, mostly in collaboration with Amos Tversky, a Stanford cognitive psychologist who did groundbreaking work on human judgment and decision-making.

[…]

“His central message could not be more important,” the Harvard psychologist and author Steven Pinker told The Guardian in 2014, “namely, that human reason left to its own devices is apt to engage in a number of fallacies and systematic errors, so if we want to make better decisions in our personal lives and as a society, we ought to be aware of these biases and seek workarounds. That’s a powerful and important discovery.”

Professor Kahneman delighted in pointing out and explaining what he called universal brain “kinks.” The most important of these, the behaviorists hold, is loss-aversion: Why, for example, does the loss of $100 hurt about twice as much as the gaining of $100 brings pleasure?

Among its myriad implications, loss-aversion theory suggests that it is foolish to check one’s stock portfolio frequently, since the predominance of pain experienced in the stock market will most likely lead to excessive and possibly self-defeating caution.

Loss-aversion also explains why golfers have been found to putt better when going for par on a given hole than for a stroke-gaining birdie. They try harder on a par putt because they dearly want to avoid a bogey, or a loss of a stroke.

Mild-mannered and self-effacing, Professor Kahneman not only welcomed debate on his ideas; he also enlisted the help of adversaries as well as colleagues to perfect them. When asked who should be considered the “father” of behavioral economics, Professor Kahneman pointed to the University of Chicago economist Richard H. Thaler, a younger scholar (by 11 years) whom he described in his Nobel autobiography as his second most important professional friend, after Professor Tversky.

“I’m the grandfather of behavioral economics,” Professor Kahneman allowed in a 2016 interview for this obituary, in a restaurant near his home in Lower Manhattan.

Daniel Engber, The Atlantic, “Daniel Kahneman Wanted You to Realize How Wrong You Are“

I first met Daniel Kahneman about 25 years ago. I’d applied to graduate school in neuroscience at Princeton University, where he was on the faculty, and I was sitting in his office for an interview. Kahneman, who died today at the age of 90, must not have thought too highly of the occasion. “Conducting an interview is likely to diminish the accuracy of a selection procedure,” he’d later note in his best-selling book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. That had been the first finding in his long career as a psychologist: As a young recruit in the Israel Defense Forces, he’d assessed and overhauled the pointless 15-to-20-minute chats that were being used for sorting soldiers into different units. And yet there he and I were, sitting down for a 15-to-20-minute chat of our own.

[…]

Daniel Kahneman was the world’s greatest scholar of how people get things wrong. And he was a great observer of his own mistakes. He declared his wrongness many times, on matters large and small, in public and in private. He was wrong, he said, about the work that had won the Nobel Prize. He wallowed in the state of having been mistaken; it became a topic for his lectures, a pedagogical ideal. Science has its vaunted self-corrective impulse, but even so, few working scientists—and fewer still of those who gain significant renown—will ever really cop to their mistakes. Kahneman never stopped admitting fault. He did it almost to a fault.

Whether this instinct to self-debunk was a product of his intellectual humility, the politesse one learns from growing up in Paris, or some compulsion born of melancholia, I’m not qualified to say. What, exactly, was going on inside his brilliant mind is a matter for his friends, family, and biographers. Seen from the outside, though, his habit of reversal was an extraordinary gift. Kahneman’s careful, doubting mode of doing science was heroic. He got everything wrong, and yet somehow he was always right.

[…]

In 2011, he compiled his life’s work to that point into Thinking, Fast and Slow. Truly, the book is as strange as he was. While it might be found in airport bookstores next to business how-to and science-based self-help guides, its genre is unique. Across its 400-plus pages Kahneman lays out an extravagant taxonomy of human biases, fallacies, heuristics, and neglects, in the hope of making us aware of our mistakes, so that we might call out the mistakes that other people make. That’s all we can aspire to, he repeatedly reminds us, because mere recognition of an error doesn’t typically make it go away.

[…]

Yet the timing of its publication turned out to be unfortunate. In its pages, Kahneman marveled at great length over the findings of a subfield of psychology known as social priming. But that work—not his own—quickly fell into disrepute, and a larger crisis over irreproducible results began to spread. Many of the studies that Kahneman had touted in his book—he called one an “instant classic” and said of others, “Disbelief is not an option”—turned out to be unsound. Their sample sizes were far too small, and their statistics could not be trusted. To say the book was riddled with scientific errors would not be entirely unfair.

If anyone should have caught those errors, it was Kahneman. Forty years earlier, in the very first paper he wrote with his close friend and colleague Amos Tversky, he had shown that even trained psychologists—even people like himself—are subject to a “consistent misperception of the world” that leads them to make poor judgments about sample sizes, and to draw the wrong conclusions from their data. In that sense, Kahneman had personally discovered and named the very cognitive bias that would eventually corrupt the academic literature he cited in his book.

In 2012, as the extent of that corruption became apparent, Kahneman intervened. While some of those whose work was now in question grew defensive, he put out an open letter calling for more scrutiny. In private email chains, he reportedly goaded colleagues to engage with critics and to participate in rigorous efforts to replicate their work. In the end, Kahneman admitted in a public forum that he’d been far too trusting of some suspect data. “I knew all I needed to know to moderate my enthusiasm for the surprising and elegant findings that I cited, but I did not think it through,” he wrote. He acknowledged the “special irony” of his mistake.

I was first exposed to Kahneman as a young grad student in 1992. Even though I was studying international relations, not psychology or economics, his 1979 work (with Amos Tversky), “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk” was already a classic that had spread throughout the social sciences.

Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow was among the issued books when I started at Marine Corps University in 2013. A point I constantly emphasized to students was that Kahneman was not just talking about other people. Even highly-trained geniuses like himself were prone to the errors he was describing. The best we could do is to train ourselves to be more attuned to biased reasoning; we would never truly escape it because it’s simply too hard-wired.

I’ve been meaning to delve more deeply into the works of Tversky and Kahneman, beyond the heuristics parts. Something else always seems to come up.

Going with the criticism above, has the work on heuristic, biases, etc. been replicated?

@Kathy: The work on cognitive biases has been repeated and confirmed many times. I first learned about them in the 1991 book How We Know What Isn’t So, by Thomas Gilovich, another researcher in that field. Anchoring bias, immediacy bias, framing bias, various others…

The Prospect Theory behavioral findings are also well-established, though there is still debate over mechanisms and whether specific observed behavioral patterns are actually irrational or not.

@DrDaveT:

Thank you.

That settles the big question on their work.

I’ve only taken two economics classes in my lifetime, and the second one was a pseudo-graduate-level class where the first thing thrown at us was Prospect Theory. As an undergraduate community college student at the time, it was an electrifying read. Tversky died a while back, the professor who taught both of those classes died last year, and now Kahneman is also gone.

I’m not an engineer or a scientist, and don’t have an advanced degree.

I read this book a few years ago because I was looking for a book that would give me an understanding of behavioral economics, decision theory, heuristics and ‘intuition’. It was well worth my time.