Foreign Policy and Elections

Politicians in office have a nasty habit of behaving completely differently than they promise on the campaign trail.

Stephanie Carvin argues for greater debate on foreign policy issues during election campaigns. Her country, Canada, will shortly hold elections and believes they should learn from the UK’s recent experience.

After the UK foreign-policy-free election, the coalition has made major and significant policy decisions which affect foreign relations. Some of the significant ones include:

- Ring-fencing the Department for Foreign International Development (DFID) budget

- Taking BBC World Service from the Foreign Office and putting it under control of the British Broadcasting Corporation

- Substantial cutbacks in military spending

- Actively lobbying for and participating in a NATO mission in Libya

- Continuing participation in Afghanistan

There was no debate on any of these issues. For Afghanistan, all that the leaders spoke of was their trips there and meeting the troops. It could not be said that there was a major debate about the scale, scope and vision of the mission. So should there have been a debate on the UK’s foreign policy priorities and its role in the world? And why wasn’t there one?

She offers several plausible explanations but then brushes off the objections:

[G]overnments are going to have to deal with foreign events, and without some kind of guidance, or debate or understanding of what our interests are and what our priorities should be, then there can be major surprises later on.

Even if it must take place in terms of vague generalities, a foreign policy debate is worth having. It is worth knowing where political parties stand on R2P, development, the United Nations (and UN Security Council) international organizations, etc. Broader ideas and goals should be outlined even if, inevitably, events cause change and reversal later on. While I do not anticipate huge cuts to Canadian defence spending nor a major change on our alliance policies, it would be nice to know what the Conservative (UK and Canadian) line on “the Responsibility to Protect” is – since we seem to be doing a lot of it lately.

As a fellow foreign policy wonk–and as a believer in the merits of democratic debate in general–I concur with all of that.

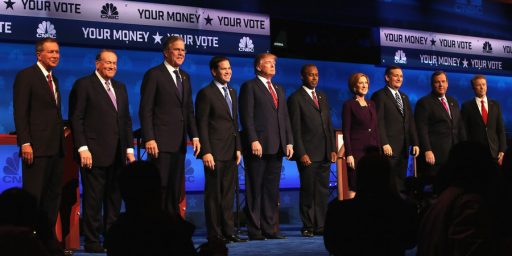

Then again, foreign policy is very much a part of American presidential debates. Unlike our Anglosphere cousins, our campaigns stretch on for a ridiculously long time. (Indeed, they seem very much never to end, with one running right into the next.) Speeches about foreign policy, especially war policy, are part and parcel of the campaign. And there’s usually an entire debate focused on the issue of foreign affairs.

But there’s a wee problem: Politicians in office have a nasty habit of behaving completely differently than they promise on the campaign trail. This is especially true in foreign policy.

The same argument can of course be made about domestic politics. But, in parliamentary systems such as the UK and Canada, there’s a reasonable harmony between what’s promised and what’s delivered in terms of program, if not impacts. In presidential systems like ours, it’s much more complicated given the horse trading inherent in the system.

But in foreign affairs, heads of state often act 180 degrees off of what said on the campaign trail. Recall George W. Bush’s promise for a more humble foreign policy that eschewed nation building. And Barack Obama’s promise to close Gitmo and keep us out of optional wars. Both men, I firmly believe, honestly meant what they told us. But the realities of being the man in the Big Chair are simply different than those of the theoretician.

If nothing else, I suppose, getting candidates on the record during campaigns allows us to hold them accountable the next time if they break their promises. But there’s scant evidence that Americans, at least, vote on foreign policy. The fact that there’s elite consensus between the parties towards military intervention doesn’t help, either, in that there’s not much of an alternative. The only difference between the two major candidates in 2008 was that John McCain made it clear that he favored muscular support of democracy; both were just as apt to actually engage in it if elected.

Ask the average American voter where Algeria is. If they know it’s because it happens to be next to Libya where we happen to be involved. Two months ago they didn’t know where Libya was. The American voter is utterly ignorant when it comes to foreign policy. It’s an ignorance born out of their equally impressive ignorance of history.

So during campaigns politicians tell people what they want to hear. Since the voters have literally no idea at all what any of it means, this is all completely pointless. Blah blah blah we’re the greatest blah blah blah.

They want the truth? They can’t handle the truth.

“My fellow Americans, here’s what I’ll do: I’ll hold onto American power and influence however I can. I’ll minimize the odds of us getting bitten in the ass in any way that I can. Democracy? Love it, who knows, maybe I’ll get a chance to move the ball forward.

In attempting to achieve those ends I’ll do whatever the hell it takes. I’ll make deals with people I wouldn’t trust to shine my shoes. I’ll proclaim our ideals loudly one minute and sell them out the next. I’ll pretend I know things I don’t know. And the reverse. I’ll get some right, I’ll get some wrong, we’ll win some, we’ll lose some. And I’ll tell you what little I think you people can absorb, because frankly you don’t really give a damn.”

That’s what every president in my life, regardless of party, could honestly have said.