Income Versus Living Standard Inequality

Kevin Drum leads off an otherwise interesting post on the shifting risk burden in our economy with a rather misleading statement:

On a per-person basis, our economy has nearly doubled over the past 30 years, but that growth has been wildly uneven. Instead of everyone seeing their incomes double, the poor and the middle class have seen almost no growth, while the rich and the super-rich have seen their incomes skyrocket.

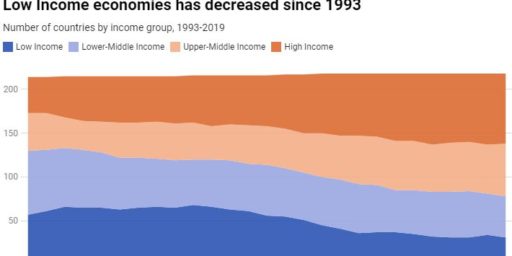

It’s undeniable that, in real terms, there has been an explosion in the amount of wealth at the top of the economic chain. Still, two caveats should be noted.

First, we need to be careful of the ecological fallacy. Just because the income levels of “the poor” or “the middle class” have not risen substantially does not mean that the income of many who were poor and middle class, or the children of many more who were poor and middle class, have not. While Bill Gates had the advantages of moderately rich parents, many if not most of today’s mega-billionaire dot.com boys rose out of mundane financial circumstances.

Second–and more importantly– “income” is not the same as “standard of living.” In every meaningful sense, “the poor” and “the middle class” are wealthier than they were thirty years ago. Whether we’re talking about the rate of home ownership, size of our homes, the ability to eat at restaurants, the luxury level of their automobiles, the quality of medical care, access to exotic foodstuffs, gadgets from personal computers to VCRs to DVD players, or whatever, the “middle class” of today arguably live better than the “rich” of 1976 and the “poor” better than their bicentennial forebearers, too.

Indeed, while I have no idea how one would measure this, it’s quite possible that the standard of living gap between “poor,” “middle class,” and “rich” has tightened over the last thirty years, even as income equality has grown. As the cost of creature comforts has fallen, the number of things that the rich can afford that the poor can not has, too. For example, there are now more people who can afford to buy their own Lear jets. Yet, thanks to deregulation and the appearance of low frills carriers let JetBlue and Southwest, commercial air travel is now available to all but the very poorest. That wasn’t the case in 1976.

Yes, Oprah Winfrey can afford a private chef. But even low wage workmen routinely take their families to any number of moderate priced chain restaurants. Thirty years ago, dining out was a special event for folks in the middle class.

You miss the main problems with the increasing income gap. Focusing on opportunities for modest consumption like eating at Olive Garden belie the undeniable fact that people from the lowest three quintiles in earning power are spending much higher percentages of their income on housing. Additionally, the rise of health care costs–while not affecting as many as the housing crunch–is the highest determining variable for middle classes declaring bankruptcy.

Lower savings rates reflect these structural changes.

Piggybacking off of Triumph, you also miss the main reason for athe bility to afford higher-priced products and services by lower-wage earners and that is debt. Debt levels for families have skyrocketed with an easier access to capital and multiple refinancing of homes. These escalating debt levels for families are a dangerous thing for our future economy, and should not be underestimated. The ability to afford luxury items is a fallacy that is only being propped up by increased credit.

Are the roads and schools and police and fire and health services for the poor better or more readily accessible. 45% of the country is without insurance as opposed to 25% in the 70’s and the cost of higher education has skyrocketed while education assistance programs have decreased. So it appears all the benefits have accrued to the wealthy, while the poor just have more cheap junk than they did in the70’s…enough to keep them ignorant and compliant…just how rethugs like them.

Steve, it seems to me that pretty much this whole apparent discprepancy could be explained by the upward bias in CPI. That seems to be established and accepted by the economists who care about these things, yet it hasn’t become common knowledge. And because it hasn’t, we’re all still trying to explain why those false inflation figures don’t match up with economic reality as we perceive it.

Why is that?

So? Is this just a recent phenomenon due to the low interest rates and run in housing prices? Or is it the case that people in those quintiles have more “housing” as well? Simply looking at that statistic in isolation and pronouncing it a bad thing is dubious.

Right, but to what extent are bad governmental policies the driver behind this? Health care is going to continue to rise at alarming rates in part because the government is going to be spending lots of money on retiring baby boomers. Further, the way benefits are treated in terms of a tax exempt benefit means that part of the reason that wages has stagnated is due to higher health care costs. Employers look at total compensation not wages and then health care when hiring an employee and in making other decisions.

Changing health care and how it works might help, but turning it all over to the government could be problematic for the reason noted above about medicare spending.

Yes and no. While your point about home refinancing could very well be the main factor in triggering the next recession, the idea that because luxury goods are cheaper doesn’t automatically mean that people are worse off. In fact, that is a highly counter-intuitive view to take. The computers of today are about the same as they were several years ago, but have quite a bit more in terms of features. Same with things like cameras. You standard point-and-shoot film camera is so cheap now, I bought one for my 8 year old. VCRs were once luxury goods, but now when they break you throw them out and buy a new one. Even DVD players are much much cheaper. Declining prices means a higher level of welfare can be attained. This is basic micro-economic theory. It is so well accepted by economists we can practically think of it as a fact.

Measuring standard of living is hard. Income is often used as a proxy, but a better variable is probably consumption expenditures. Of course, even rising consumption expenditures is not always a “good thing” in that people might be reducing their savings rate or even savings to do it. This will mean lower levels of consumption in the future than there otherwise would be.

It is a difficult issue to untangle, and frankly over the years Drum has shown himself to be completely inadqueate for the job.

John,

While there is indeed an upward bias to the CPI, the questions is by how much. Granted if we new that answer and correct for it, it would almost surely turn out that the result is different and in a good way. For example, the CPI is not a measure of the cost of living, and as such it doesn’t capture subustitution which can blunt the impact of price changes, especially price increases. Also, the CPI isn’t very good in terms of capturing the arrival of new technologies. Alot of smart people work hard at minimizing these things, but the exact magnitude isn’t really known. But you’re right this should be kept in mind when discussing this topic.

Just because the income levels of “the poor†or “the middle class†have not risen substantially does not mean that the income of many who were poor and middle class, or the children of many more who were poor and middle class, have not.

Completely irrelevant. If 0.0001% of the poor population rise from rags to spectacular riches, this does not change Kevin’s point in the slightest. His point was not that some small speck rose up. It’s that the vast, vast majority didn’t participate.

What’s hilarious is that *you* are making the ecological fallacy – not Kevin. *You*, James, are highlighting extreme outliers to attempt to refute the valid point that almost everyone of the poor didn’t make it. The simple fact is that the population of “winners” here is about 1% of the population *as*a*whole*. And the people you are talking about – the rags, or kind of rags, to super riches – are an even smaller proportion of the population. Consequently, it’s you who are falling subject to the economic fallacy – not Kevin.

As to your second argument, tell that to the 40 million – larger than the population of Canada or the entire state of California – of uninsured. I’m sure that when their children come down with life threatening diseases, they can be comforted by the DVD player they still can’t afford.

My god. You people actually believe this stuff.

Stunning.

I believe that if you actually check the data on this, the idea that only a “speck” rise up is vastly misleading. While income mobility is not cast in stone, and has declined somewhat in recent years it is much larger than your miniscule number.

Well duh, if you set the criterion for winning at the richest 1% of population, then if it is a given that 99% are going to be losers. You have basically set things up so that your position is unassailable to data and real world experience.

No, they will be comforted by the fact that they will be able to get treatment irrespective of the ability to pay. Seriously, I suggest you look into how health care works vs. basing it off of the movie John Q.

So is your ignorance.

Hal,

I’m not accusing Kevin of committing the ecological fallacy, merely noting that one could make that leap from his statement. I’m not arguing that, because a few rich people used to be poor that, therefore, all poor people are now rich. I use the example of the billionaires simply to illustrate that a given individual’s social class is not static.

Really? – 135,000,000 Americans don’t have insurance? That’s incredible – it’s tripled since last year. Or maybe not?

Steve: Bite me.

he idea that only a “speck†rise up is vastly misleading

Wow. Care to back that up with data, or are you just blowing CO2?

then if it is a given that 99% are going to be losers.

Um, no. At issue is the income *distribution*, in which the winners take pretty much all. That’s the whole point of Kevin’s post. It’s perfectly possible to have a system where the richest 1% *didn’t* gobble up 40% of the income. That would be a different *distribution*. Geez. And you call me ignorant.

they will be able to get treatment irrespective of the ability to pay.

Wow, stunning. Pretty much every study on this has shown that people without health care do *not* go to get treatment until it is way too late. They do not get the drugs they need. They don’t get the care they need. And it’s comforting to know you get your information from pony-land.

So is your ignorance.

Thanks again, Dr. Science.

James:

I use the example of the billionaires simply to illustrate that a given individual’s social class is not static.

Irrelevant to the argument. The argument isn’t that *some* people don’t win. It’s that the vast, vast majority don’t. So the fact that some people win is simply a red herring.

While there is indeed an upward bias to the CPI, the questions is by how much.

As I recall, the Boskin commission concluded (and Greenspan agreed) that the upward bias in 96 and (likely) for many years prior was about 1.1 percentage points per year. The BLS corrected about .4-.5 percentage points of that bias, but more recent research (cited by Boskin) indicates other areas of bias and concludes that the total current upward bias is in the range of .8-.9 percentage points per annum.

You are correct that CPI is not a cost-of-living measurement. It isn’t a true guage of inflation, either. The BLS makes it clear that CPI is neither of those. It’s just the best stand-in we can find for the time being.

However, while they don’t capture all of it, the CPI does capture some degree of substitution. The upper and lower level substitution problems were among the things the Boskin Commission pointed out, and the BLS adjusted. The failure to properly account for new technology was also pointed out by the Boskin commission, but it’s not really possible to fully resolve that problem.

Still, it frustrates me that we KNOW these comparisons between different years are flawed, yet the public debate doesn’t account for it; the figures are cited as if they are accurate.

Hal,

Why yes I do.

Got anything to back that up or are you just blowing CO2? And yes, we are talking about an income distribution, but the idea that a tiny fraction owns it all is an exaggeration. IOWs you’re wrong.

Finally, you defined winners as about 1% of the population. So my point still stands, all your ranting and nonsense aside.

Really? What studies? Got a link? If this is so ubiquitous as you indicate a link should be easy to post.

Sorry, it is the law. Any hospital has to treat a patient (if it can–i.e. has the necessary staff, equipment, etc.) that comes through the doors irrespective of ability to pay.

And the data I linked too says you are ignorant of the facts and that income mobility is indeed real. No matter how much logic you bring to bear on this issue, if the facts contradict you, you are wrong.

This has always been something of a political hot potato that everybody keeps tossing around. Boskin’s numbers maybe right, but nobody is willing to step up and say, “Okay, inflation adjustments are now CPI – .75.” The problem also is that that 0.75 or whatever number one likes tends to rest on assumptions which don’t apply evenly across the board.

Yes I know this was the point of things like switching to a geometric means for the index as well as the chained index. However, the latter is rather dicey in that it is very complicated and changing assumptions can lead to different results. Still, there are other types of bias that the Boskin Commission missed, such as the effects of discount sales for items that have a long shelf life. For example, a sale on canned goods affords consumers the opportunity to build up a stock of the goods, and then draw down on that stock when prices return to normal. Handling something like this is very difficult to get a handle on as the mathematics get complicated very quickly.

Yes, I know. We’ve seen some ignorance of the data right here in this very comment thread.

Hal:

If you define “winning” as the top 1%, then certainly few “win.” If we define it as a middle class lifestyle circa 1976, more are “winners” now than then.

I don’t question, btw, that health costs and such are skyrocketing. The reasons are manifold, though, not the least of which is vastly improved technology and medicine. “Health care” is not a static good such that one 1976 “unit” is easily comparable to a 2006 unit.

James,

If you define “winning†as the top 1%, then certainly few “win.â€

Again, if the top 1% income earners get the lion’s share of the income, then Kevin’s point regarding a “winner take all” economy is correct. You’re completely ignoring the distribution, which is the entire point here.

There are numerous ways of looking at data that can be used to make your point.

For example home ownership is at a record high.

But look at the record.

From 1900 to 1940 it stayed very constant at around 45% of the population. By 1950 it rose to 55% and in 1980 it reached 64.4% In 2000 it was 66.2%.

So what you had was an era from 1940 to 1980 when home ownership expanded massively– almost a 50% gain. But since 1980 it has only expanded 3%.

So yes, you can say we are at record home ownership. Or, you can use exactly the same data to show that since 1980 home ownership has

stagnated with virtually no improvement, especially compared to the previous era.

Now, if you are going to use the home ownership data to demonstrate how living standards are changing the stagnating argument is the correct line of analysis to take.

Right?

So is my response to Steve lost in the ozone?

Hal,

I’m not ignoring the distribution issue, just arguing that income is only one variable and that lifestyle is ultimately more important. The distribution of goodies across the board is much greater than it was in 1976 and, as I note in the post, the lifestyle gap between the classes has likely shrunk (granting that it’s difficult to quantify).

The distribution issue, especially the “risk” issue to which Kevin alludes, is interesting and worth discussing in its own right. That’s a separate discussion, though.

Sorry Bandit…I meant 41%…

Steve — Yes the Boskin comittee recommended changes to the cpi and BLS implement them.

Moreover, they went another step and created the cpi-rs that went back historically and recalculated what the cpi would have been using the new methodologies. It shows inflation was about half a percent lower.

Census now uses the cpi-rs to calculate the real income data used for historical comparisons.

James,

The quote you post from Kevin states the issue quite clearly:

Instead of everyone seeing their incomes double, the poor and the middle class have seen almost no growth, while the rich and the super-rich have seen their incomes skyrocket.

So, if it hasn’t seen any growth, then it doesn’t matter if there’s more goodies as they’re essentially all going to the rich and the super rich.

The fact that some people who were poor participated in this does nothing what so ever to rebut this.

Hal: There’s not much point in responding to your arguments if you’re simply going to repeat the same thing over and over again.

James, so your point #1 in your original post is really just an asside, and all Steve’s arguing about income mobility is really just a red herring? You actually agree with Kevin’s points?

It’s either that you’re point is irrelevant, or you’re actually trying to make a point. And that point is surely something more than “some poor people win, so there”.

BTW, is my response to Steve ever going to show up or do I have to repost? Your system claims I have already posted it, so I assume you have it.

If you examine a wide range of data series you find that almost without exception they show the US experienced a sharp slowing of real income growth or improving living standards around 1980 and that the sharp increase in income inequality

since 1980 has made the problem worse.

Those saying this is incorrect need to demonstrate that for some reasons the data

became much less reliable about this time.

I see many people talking about problems with the CPI, but I have yet to see any serious arguments that the CPI became less reliable after 1980 then it was before 1980. Even Gorden with his studies never claimed that the CPI was more accurate in earlier eras.

So do you want to adjust the CPI down so we see stronger growth after 1980 but not make the same adjustment to the pre-1980 data?

Spencer:

Surely, you’ve heard of regression to the mean? Obviously, if something expands from 45% to 65% in relatively short order, it’s not going to keep expanding at that rate. There’s simply radically less room for growth.

We’re likely pretty close to the theoretical high here. A substantial chunk of the population is mobile and otherwise not in a position where buying a home makes much sense.

I didn’t own a home until I was 31 years old, despite having at various points before that been in a financial position to afford one. After graduating college, I was a single Army officer subject to the whims of the service, including rapid repostings. It made no sense for me to own a home. As a graduate student, I couldn’t afford a home nor would it have made sense to buy in any case since I’d be moving in 3 years. Then, I had a one-year appointment as a sabbatical replacement professor and then took a job teaching community college that I rightly figured I’d be leaving once a better opportunity presented itself. Finally, upon securing a tenure-track position at a better institution, I jumped into the market.

Most young people, especially single young people, are never going to be in a position where buying a home makes sense even if it’s affordable. And even the lack of affordability for a 20-year-old single is hardly something we would expect the economy to “fix.”

Hal:

No, my first point is that “the poor” and “the middle class” and “the rich” are not the same people in 2006 as they were in 1976. Obviously, few of the 1976 poor grew up to be Bill Gates. But some substantial portion moved into the middle class and some sizable number of the middle class moved into the wealthy class. Presumably, through bad decision-making, bad luck, death, inheritance redistribution, and other factors, some sizable portion of the 1976 “rich” have down-migrated as well.

Obviously, one would rather start “rich” than “poor,” for a variety of reasons. The poor and the children of the poor have numerous barriers to success that the rich and their children lack in their quest for continued success (although regression to the mean does tend to move the offspring of the super rich further down the ladder than their parents). Still, there is substantial mobility at the individual level that Marxian focus on class misses.

The second point, that income and lifestyle are not synonymous, though, is my main point, which is why it gets three paragraphs and the other gets only one.

Forgive my ignorance but everytime I see a large percentage without healthcare I wonder how they arrive at that figure.

The reason I ask is because I work with a small family practice clinic. I’m in an extremely poor city in the extremely poor south and our patient demographics is largely from the most notoriously poor community. Yet nearly everone has some kind of coverage. If they work they have BCBS. If they don’t they have Medicaid or Medicare or both.

Until last year, most of our patients had better dental coverage than the doctors and nurses who took care of them. Now our local university offers dental at an increased rate to employees.

I’m just curious how these figures are acheived. And if the methodology is sound, how the heck did these hovellites in Lower Alabama avoid being included in this statistic?

In MadMatt’s USA today they stipulate:

“The percentage of working-age Americans with moderate to middle incomes who lacked health insurance for at least part of the year rose to 41% in 2005, a dramatic increase from the 28% in 2001 without coverage, a study released on Wednesday found.”

So, we have a group of workers, not all Americans. A group of workers with some mysterious income range who represent the 41%.

But by my math (which I am NOT very mathematically inclined so correct me if I’m wrong):

if we have 298 million (CIA Fact Book)

and

according to the article there were 45.8 million sans insurance

isn’t that 18%?

Even that seems high from what I see.

Lunacy

Non economist, statistician here, but I get the impression from those who are upset that the top 1% has a lot of income-what do you propose to do to change it? I don’t think “it’s not fair” is a good model to work on, and I think communism pretty much proved itself a failure.

Spencer,

I guess it depends on your biases doesn’t it? If we are talking about things like the nominal price of oil, then by God yes we are at all time record (not really), but when we really are at an all time high in home ownership (with admittedly very, very slow to no growth over the last decade or two) then no, it is stagnate.

IIRC they didn’t implement everything, but it is good to know that they are using the better index number in calculating these series.

I’m not arguing for such a selective use of the CPI. However, I’m pretty sure that all sources of bias have not been removed and quanitfying them is highly problmatic. The point is that if we did adjust incomes correctly, then things would look better. Maybe not a heck of alot better, but better none the less.

Hal,

Not quite. I’ll leave to you as a homework assignment. Oh, and it isn’t that there is no growth in incomes at the lower end, just that the growth is not all that great.

The problem here Hal, is that you seem to assume that that there is no income mobility people, move from one income quintile to another all the time. Some don’t and some move gradually. For example, college students often rank at the bottom of the income distribution, but upon graduating and finding a job often move to a higher quintile, such as the middle quintile. I’ve pointed to some of the data on this, but you just march on completely oblivious to such data. And you haven’t supported any of your assertions so far.

And in any event as has been pointed out, income does not translate into standard living very easily save when we can take into account individual levels of welfare. For example, if income stays the same for a given individual, but he has new goods from which to consume from that move him to a higher level of welfare, then he is strictly better off. Now, this doesn’t have to be the case, but the income distribution does not capture this kind of change.