Classifying Countries by Income

What constitutes a "low income" or "high income" country?

Yesterday, Dave Schuler came across an article citing Thailand as a “poor country” and objected:

With a median household income of around $7,000/year, I would characterize Thailand as a “middle income” country. I think that countries with median household income below about $7,000 are low income (India, Egypt), countries with median incomes from $7,000-$15,000 (Russia, China, Brazil, Argentina) are middle income and countries with median household incomes greater than $15,000/year are rich countries.

Offhand, those thresholds strike me as both too low and inadequate. At a minimum, purchasing power parity would need to be brought into it.

The World Bank, the premier intergovernmental organization for international development, “divides the world’s economies into four income groups: high, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low.” And Dave’s instincts aren’t far off:

The income classification is based on a measure of national income per person, or GNI per capita, calculated using the Atlas method. In 1978, the first World Development Report introduced groupings of “low income” and “middle income” countries using a threshold of $250 per capita income as threshold between the groups. In the 1983 WDR, the “middle income group” was split into “lower middle” and “upper middle” groups, and in 1989 a “high income” country definition was introduced.

Since then, the thresholds to distinguish between the income groups have been adjusted for prices over time. As of 1 July 2019, low-income economies are defined as those with a GNI per capita, calculated using the World Bank Atlas method, of $1,025 or less in 2018; lower middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita between $1,026 and $3,995; upper middle-income economies are those between $3,996 and $12,375; high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,376 or more.

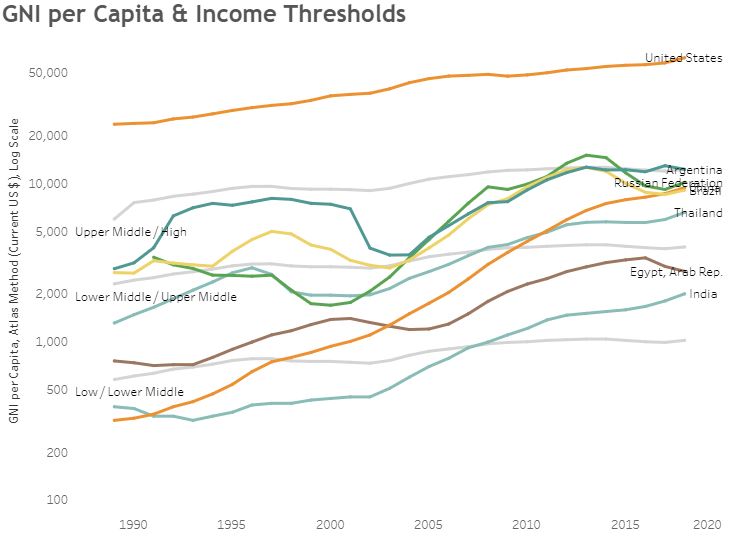

Here’s a plot of the countries Dave mentions over time, plus the United States:

As you see, only India and China among them have been “low income” during the last three decades and none of them have been “low income” since roughly 2008. Thailand has been in the “middle income” categories throughout the period. And, contrary to perception, Russia and China are both quite close to “high income” status—which Russia briefly achieved during the last energy price boom. Yet, the United States is in its own stratosphere despite Russia and China routinely being touted as “peer competitors” in the national security space.

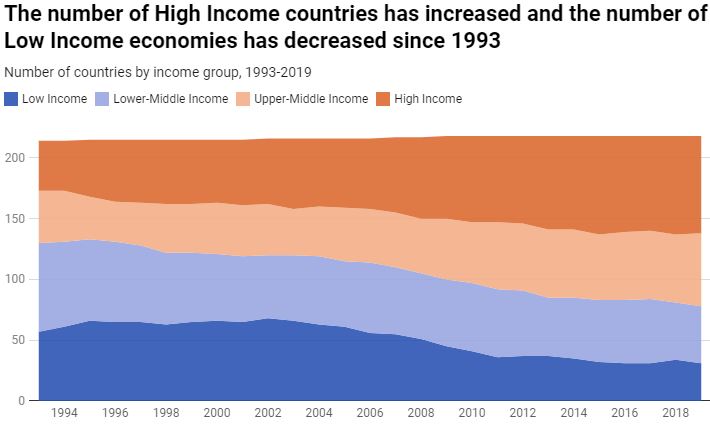

The good news is that there are far fewer “low income” countries than there were a generation ago.

Because most parts of the world have experienced considerable economic growth in recent decades, and the classification thresholds are held stable in real terms, there are now fewer low-income countries and more countries have gained middle or high-income status. Just since 2003, the number of low-income countries has nearly halved, declining from 66 to 31 in 2019. The number of high-income countries is currently 80, up from less than 50 in the 1990s. The number of middle-income countries is 107 (60 UMICs and 47 LMICs) and has not changed much as countries have transitioned both in and out of this group. The chart below summarizes the number of countries in each group over time.

The linked version is interactive but the trends are unmistakable: the “low income” share is much smaller and the “high income” share is much higher.

And, what’s true of countries is also true of people:

The changes are even starker when looking at the share of the world population that live in each type of countries. The vast majority (75 percent) of people currently live in countries defined as lower or upper-middle income countries. As large countries, such as India and China, have transitioned from low income countries to middle income countries, the population shares have shifted dramatically. In the 1990s, more than 6 in 10 people of the world’s population lived in low-income countries, while today it is just about 1 in 10.

Of course, income inequality within states isn’t addressed here. Wealth may very well be concentrated among a relative handful of elites.

Beyond that, my instinct remains that $1,026/person is an absurdly low threshold to escape “low income” status and $12,376 is an absurdly low threshold to be declared “high income.” (Granted, those are 2019 numbers.) Indeed, $12,760 is the current poverty threshold in the United States. The World Bank, though, anticipates that objection:

With only a small share of the world currently classified as “low income” and as the thresholds not having changed since 1988 (in real terms), critics argue that these income groups are losing relevance, and are somewhat arbitrary and dated.

There are many ways of grouping economies and organizing analysis of development data, and the income classification is only one of many. Yet, the absolute nature of the thresholds, and the long history of the classification scheme, provide a useful way of tracking progress over time. And analysts can always select and analyze data for custom groupings using data from our Databank.

It is important to emphasize that the income classifications are intended to aggregate and analyze data for groups of similar economies. Among other things, income classifications are used in the WDI and SDG Atlas to shed light on the following questions:

*Which type of countries have more weight in the global economy?

Which is fair enough. As with many questions posed in social science, the usefulness of the definition really depends on what question you’re trying to answer.

My instincts on the income thresholds are based on a sense of what sort of lifestyle an individual earning that amount could live in a developed country. It may well be that $1026 goes a decent way in much of Egypt—although it certainly wouldn’t in Cairo.

But even using the World Bank’s own criteria, surely India carries far more weight in the global economy than Thailand or Egypt?

Lest we get too full of ourselves Luxembourg has a much higher per capita income than we do with much less income inequality. Japan has a pretty high median household income with much less income inequality.

And my comment was pretty focused on one point: Thailand isn’t a poor country although it does have poor people in it. Characterizing it as a poor country is dated. We’re a rich country with some people a lot richer than others and a very small number of genuinely poor people which we’re not doing enough to ameliorate.

This list (GNI per capita, ppp) is what you are looking for.

It has the US at 66K and Thailand at 18.5K. Still a very noticable difference, but much less than the 66K vs. 7K when you look at nominal numbers.

Also, the y-axis of your first graph isn’t exactly helpful when comparing countries.

Even better would be median GNI per capita (ppp), but those numbers aren’t easily available (if at all).

@David Schuler:

Luxemburg is a terrible example. It has only 634,000 inhabitants and a large financial sector serving other wealthy countries around it. Better to look at Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, etc. (But not Norway, because they have a lot of natural resources.)

@drj:

The only reason I mentioned Luxembourg is that the country has the highest median household income in the world. I recognize it’s an invidious comparison. But so is comparing the U. S. with Sweden or Denmark. In addition to being one of the countries with the highest median household incomes we’re the largest country with a high median household income.

I would argue that this metric has nothing to do with global impact, and is primarily a development metric.

I would also note we are dealing with average here. As such, interpreting the numbers does, ultimately, require looking inside the case.

@drj: The graphs are both World Bank generated. And both use GNI/capita.

@Steven L. Taylor: Agreed. But that’s literally the first question IBRD says they’re using these data to answer.

@James Joyner:

I think I am missing something.

Wasn’t the initial question about pollution?

@Steven L. Taylor: “Among other things, income classifications are used in the WDI and SDG Atlas to shed light on the following questions:

*Which type of countries have more weight in the global economy?”

Shouldn’t the classification also depend upon the cost of living in an area? Its often (rightly in my opinion) pointed out that an income of say $50,000 goes a lot further in a small midwestern town than in downtown New York City. Wouldn’t that be even more the case when comparing different countries?

This feels like the ever-popular “what is middle class?” debate.

@David Schuler:

Okay, Dave. If you mean this comparatively, I guess you may be correct. But the income inequality indexes tell a different story.

But let’s look at one thing about the US: Housing.

Let me get the owner-occupied homes out of the way first. In 2018:

Back of the napkin math:

That’s about 48m households with mortgages. 20.9% of those households are cost-burdened–about 10m.

Oh, but now the real fun begins…renters. (PDF from the GAO–stats for 2017.)

Renters account for 36% of 126.224m households–about 45.44m.

48% of those are rent-burdened, defined as spending more than 30% of their income on rent. Half of those spend 50% or more of their income on rent:

So, roughly 10.9m renting households spend either 30-50% of income for housing, and another 10.9m spend more than 50% of income on rent.

So, ~31.8m out of ~126m households are financially burdened by a basic need. Hell, that’s only 25% of households.

Let me emphasize this: these aren’t millions of people…millions of households.

Oh, lest you say it’s those damn Democrat Party run cities of Leftist Big Government Marxists:

44% of non-metro renters are cost-burdened.

Let’s have a healthy, malignant cheer! Say it with me!

U-S-A.

Oh come on; you can do better than that! With feeeeeeellllling this time! Scream it like we just aced Bin Laden again!

YOUUUUU!!!!!

ESSSSSSS!!!!!

EHHHHHH!!!!!

Now back to you regularly scheduled weekend leisure.

A person making $12,760 in the US is, on a PPP basis, earning more than 83.5% of the people on the planet and has an annual income 4.5 times the global median.

@Kurtz: Isn’t this where somebody is supposed to say “well, renters who are overburdened shouldn’t be living in such large, expensive apartments and should be relocating to areas where their rents will more closely match their incomes?”

@Stormy Dragon: And you don’t see the “what’s wrong with this picture” quality of that statement?

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Haha. I’m sure that’s the immediate response from a chunk of people. And please make that the hill…

😉

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

If global income was perfectly equal, on a PPP basis, we’d each have to live on an annual income of $17,500

If you earn more than that, then you’re part of “what’s wrong with this picture”.

The problem is that the cost of things are very different in each country. So, even with PPP is difficult to calculate how much people in each country are have in fact more income than people in other countries. And high income and low income is still the better way of trying to make this distinction, but it’s still far from being accurate.

Interesting that high income countries has increased so markedly.

Not having the source stats. (looks like World Bank has changed it’s pagination and a quick look doesn’t find source data: grrr) here’s a guess:

Due to the massive shift of central and eastern Europe from middle income to high income since becoming part of the EC/EU? (Plus in Asia South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore now high income?)

@Stormy Dragon:

Why is why I’m confident in declaring the US a “rich country” by this metric. But, while I agree PPP has to be considered, it also clouds the issue. If you can get by in a place on $1 a day, it’s because it’s a poor country.