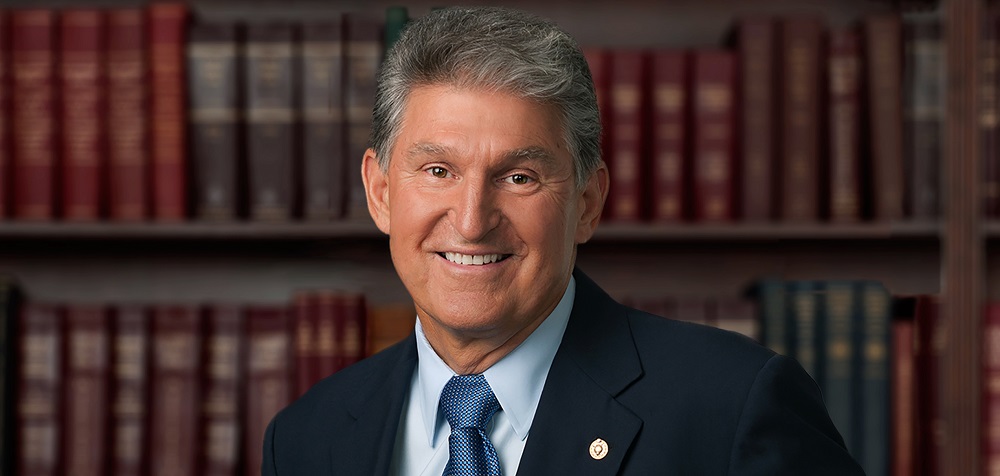

Joe Manchin’s Conflict of Interest

The most important man in the Senate got rich the old fashioned way.

In story on the front page of today’s NYT, Christopher Flavelle and Julie Tate describe “How Joe Manchin Aided Coal, and Earned Millions.” It’s a story that begins long before he was West Virginia’s governor, much less a United States Senator.

On a hilltop overlooking Paw Paw Creek, 15 miles south of the Pennsylvania border, looms a fortresslike structure with a single smokestack, the only viable business in a dying Appalachian town.

The Grant Town power plant is also the link between the coal industry and the personal finances of Joe Manchin III, the Democrat who rose through state politics to reach the United States Senate, where, through the vagaries of electoral politics, he is now the single most important figure shaping the nation’s energy and climate policy.

Mr. Manchin’s ties to the Grant Town plant date to 1987, when he had just been elected to the West Virginia Senate, a part-time job with base pay of $6,500. His family’s carpet business was struggling.

Opportunity arrived in the form of two developers who wanted to build a power plant in Grant Town, just outside Mr. Manchin’s district. Mr. Manchin, whose grandfather went to work in the mines at age 9 and whose uncle died in a mining accident, helped the developers clear bureaucratic hurdles.

Then he did something beyond routine constituent services. He went into business with the Grant Town power plant.

Mr. Manchin supplied a type of low-grade coal mixed with rock and clay known as “gob” that is typically cast aside as junk by mining companies but can be burned to produce electricity. In addition, he arranged to receive a slice of the revenue from electricity generated by the plant — electric bills paid by his constituents.

The deal inked decades ago has made Mr. Manchin, now 74, a rich man.

While the fact that Mr. Manchin owns a coal business is well-known, an examination by The New York Times offers a more detailed portrait of the degree to which Mr. Manchin’s business has been interwoven with his official actions. He created his business while a state lawmaker in anticipation of the Grant Town plant, which has been the sole customer for his gob for the past 20 years, according to federal data. At key moments over the years, Mr. Manchin used his political influence to benefit the plant. He urged a state official to approve its air pollution permit, pushed fellow lawmakers to support a tax credit that helped the plant, and worked behind the scenes to facilitate a rate increase that drove up revenue for the plant — and electricity costs for West Virginians.

Records show that several energy companies have held ownership stakes in the power plant, major corporations with interests far beyond West Virginia. At various points, those corporations have sought to influence the Senate, including legislation before committees on which Mr. Manchin sat, creating what ethics experts describe as a conflict of interest.

As the pivotal vote in an evenly split Senate, Mr. Manchin has blocked legislation that would speed the country’s transition to wind, solar and other clean energy and away from coal, oil and gas, the burning of which is dangerously heating the planet. With the war in Ukraine and resulting calls to boycott Russian gas, Mr. Manchin has joined Republicans to press for more American gas and oil production to fill the gap on the world market.

But as the Grant Town plant continues to burn coal and pay dividends to Mr. Manchin, it has harmed West Virginians economically, costing them hundreds of millions of dollars in excess electricity fees. That’s because gob is a less efficient power source than regular coal.

We’ve long known, of course, that he’s backed by Big Energy and that he votes in their interests. And, since his family owns an energy business (his share of which is nominally in a blind trust but, c’mon) he naturally benefits. But, to the extent that his interests simply aligned with those of his constituents, it’s never struck me as all that problematic.

But there’s much more than that going on here.

This account is based on thousands of pages of documents from lawsuits, land records, state regulatory hearings, lobbying and financial disclosures, federal energy data and other records spanning more than three decades. The Times also spoke with three dozen former business associates, current and former government officials, and industry experts.

The documents and interviews show that at every level of Mr. Manchin’s political career, from state lawmaker to U.S. senator, his official actions have benefited his financial interest in the Grant Town plant, blurring the line between public business and private gain.

And the private gain is not insubstantial:

Mr. Manchin and his wife owned assets worth between $4.5 million to $12.8 million in 2020, according to Senate financial disclosure forms, which provide only a range with few specifics. Mr. Manchin, who drives a silver Maserati Levante, reported dozens of assets, including bank accounts, mutual funds, real estate and ownership stakes in more than a dozen companies.

But the bulk of Mr. Manchin’s reported income since entering the Senate has come from one company: Enersystems, Inc., which he founded with his brother Roch Manchin in 1988, the year before the Grant Town plant got a permit from the state of West Virginia.

Enersystems Inc. is now run by Mr. Manchin’s son, Joseph Manchin IV. In 2020, it paid Mr. Manchin $491,949, according to his filings, almost three times his salary as a United States senator. From 2010 through 2020, Mr. Manchin reported a total of $5.6 million from the company.

The dig about the Maserati should have been edited out as it smacks of an agenda and adds nothing to the story. I’d guess plenty of US Senators drive similarly expensive vehicles. (The Mazerati SUV starts at $80,000 but the sweet spot is the $116k version—roughly the cost of an entry-level Mercedes S Class.)

That Manchin went from owning a failing carpet store to a wildly successful energy company in a year, based on his actions as a state legislator, is obviously a red flag. And, frankly, it’s rather odd that we’re just hearing about it 35 years later. One would think it would have come up in one of his two successful bids for the governorship and three for the Senate.

Regardless, his wealth seems all to stem from that original deal:

Mr. Manchin describes Enersystems in disclosure forms as a “contract services and material provider for utility plants.”

The privately held company has no website. Its headquarters consist of a cluster of small rooms on the ground floor of a brick office complex in Fairmont, W.Va., that bears Mr. Manchin’s name. It has just two employees, according to filings with the West Virginia secretary of state.

[…]

Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows that Enersystems supplies a specific type of coal burned to generate electricity. And since 2002 — as far back as that data goes — Mr. Manchin’s company has had just one customer: the Grant Town power plant.

I know next to nothing about the coal business but would think it would take more than two employees to supply enough to fuel a power plant. Presumably, then, it’s basically a pass-through.

Regardless, the business actually saved the community, with a little help from Congress—and, no, not Manchin.

The community of Grant Town was built around one of the largest underground coal mines in the world. But since the mine closed in 1985, every other business has shuttered, along with the school. Many of the buildings have been condemned.

Despite its struggles, the community had something valuable to outsiders: mountains and mountains of gob.

Gob, an acronym for “garbage of bituminous,” is waste coal — low-quality material dug from a mine that is mixed with rock and clay, making it harder and less efficient to burn. For decades, dark gray gob piled up on the ground outside coal mines in West Virginia, barren heaps often reaching several stories high.

But in 1978, worried about the country’s dependence on foreign oil, Congress passed a law to encourage alternative energy sources. That led to the opening of several gob-burning plants, including Grant Town.

The developers who planned the Grant Town plant created American Bituminous Power Partners, or AmBit, to build the plant. AmBit signed a long-term contract with the local utility, Monongahela Power, to buy the electricity it produced from gob.

Why was Manchin so instrumental in all of this? Connections.

Mr. Manchin grew up in politics. His father and grandfather both served as mayor of his hometown. His uncle, A. James Manchin, was West Virginia’s treasurer. Mr. Manchin’s father was close friends with Arch A. Moore Jr., a three-term West Virginia governor whose daughter, Shelly Moore Capito, is currently the state’s Republican U.S. senator.

Those ties helped Mr. Manchin get things done, said Jack Spadaro, then a supervisor for West Virginia and neighboring states with the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, which regulates coal mines.

“He could control a bloc of votes in northern West Virginia,” Mr. Spadaro said. “If you got the Manchins behind you, you could really do something.”

Mr. Manchin used that influence on behalf of AmBit.

And, naturally, he was rewarded.

After helping to win the permit for the plant, Mr. Manchin began to profit from it.

On Oct. 5, 1989, one of Mr. Manchin’s companies, Transcon Inc., bought an old coal mine in Barrackville, five miles south of Grant Town, for $380,000, according to records in the Marion County Courthouse. That same day, he sold the property and its gob piles to AmBit for $500,000 — a profit of $120,000.

But Mr. Manchin was not only a supplier of fuel to the Grant Town plant. He also got a share of its revenue.

Shortly before the plant opened, he signed another deal with AmBit, involving yet another old coal mine that Mr. Manchin owned, this one south of Farmington, Mr. Manchin’s hometown. He leased that mine, along with the gob on that property, to AmBit. In return, AmBit agreed to pay not just rent to Mr. Manchin, but also one percent of the gross revenue from electricity generated by burning gob from Mr. Manchin’s old coal mine, according to a copy of the lease at the courthouse.

There’s a whole lot more to the story but, to sum up, as Manchin climbed the political ladder, he used to increased power to help his partners make more money—at the cost of the little people whose electricity costs skyrocketed—and he, in turn, got richer.

Again, I find it odd that someone who has had Manchin’s level of prominence so long has managed to mostly fly under the radar on this so long. One wonders who tipped the Times off at this juncture. (Oddly, while the story is on A1 of the print edition it’s easy to miss on the website. It’s in the fifth block of stories down and not illustrated, surrounded by other features that are.)

Whether any of these actions were illegal is unclear. It’s quite possible that they weren’t. It seems wildly unethical, though.

James, while the New York Times piece is perhaps the largest to date, the bulk of this has been known for years. I never understood why you continued to insist that Manchin was only reflecting the will of his constituents in his votes rather than what seems plainly to be his corruption.

@MarkedMan: I don’t spend a lot of time looking into the biographies and personal finances of politicians. That a Senator from West Virginia votes in ways that favor the coal industry doesn’t raise any red flags, since that’s what I’d expect.

@James Joyner: The thing I always look for is those few occasions when a politician’s and their voter’s interests definitely don’t overlap. Which way do they vote then? Until recently I hadn’t focused too much on Manchin, but I do look out for things like that’ll and going back a long time there was the occasional report about such things since before he was in the Senate. Enough that I had developed a definite opinion.

FWIW, he also has reputation for poorly crafted and faddish bills that he promotes heavily during his campaigns but has no real interest in. In fact, if I remember correctly there are at least a couple of times he later embraced or authored legislation that went directly against things he had championed only a few years before.

So my impression, built up over a number of years, is that he has no real values that he is willing to fight for, except for his personal financial interests. While it may be correct to say that he represents conservative voters, it doesn’t really make sense to attribute any particular philosophy to him.

Why? They’re just facilitators. They arrange to remove material from the existing large waste piles at closed coal mines. Sell it to the power plant. Hire companies with loaders and trucks to load the trucks at the waste pile, drive to the power plant, dump it. Repeat as necessary. Hire an audit firm to make sure the work is actually done, an accounting firm to keep the cash flow legal. Two seems like plenty.

Not to mention the piles of money he’s getting from normally Republican donors. And the question as to how many senators and reps are any different. And that said, without Manchin we’d have Moscow Mitch back as Majority Leader. A horrible Democrat is better than a Republican.

And, as Atrios points out, by tomorrow all the pundits will be back to Manchin’s deep commitment to representing his constituents.

Given that one of the surest ways for an individual to become wealthy in this country is to become a US senator, we shouldn’t be surprised by any of this. That another great way to become wealthy is to be a governor, isn’t a surprise either and Manchin has been both.

James: “One wonders who tipped the Times off at this juncture. ”

Imho they knew, but Manchin is a white right-winger. They probably printed it because somebody else was breaking the story.

That Manchin has become filthy rich using political connections to sell mountains of junk at great profit is not at all surprising.

Just don’t forget: Manchin, thanks to hagiographic coverage in the press and the Myth of the American Businessman, is the self-less public servant looking out for the interests of the good folks of West Virginia, while the ex-bartender AOC is the detached radical out to ruin their lives with Socialism.

Possibly worth noting that a few years ago when Dominion Virginia Power did basically the same thing — arrange for a company to remove and transport a gob pile to one of their coal-fired plants that could handle it — including a $500,000 payment from West Virginia’s state government to make it profitable for the intermediary, everyone lauded it as an enormous environmental triumph.

Of course, corruption is a family affair.

Manchin received large campaign contributions from daughter’s company amid EpiPen scandal

Not only is Manchin corrupt, but he has an ugly boat.

But all that money pouring into Manchin is legitimate political speech, permitted, nay demanded, by the First Amendment, right?

Given that this is the paper that spent all of 2016 on Hillary Clinton’s emails… I just assume The NY Times has an agenda of undermining and destroying large-D Democratic governance. They are a center right paper at the highest levels, which happens to employ a bunch of lefties at lower levels, while balancing them with garden variety right wingers in editorial.

It’s not like any of this is new information — it’s been circulating on the left for ages. The NY Times just chooses to give this portion of the left a platform at the most opportune time for their agenda.

Why now? Make Manchin’s corruption an issue, try to push him out of office and stop a tax on 100M-aires.

There’s a lot of very good reporting at The NY Times, and we should be concerned with corruption, but they apply different rules at the editorial level for Republicans and Democrats.

@Gustopher: Indeed. There is a Sulzberger family fortune to take care of.

And I’d take “garden variety” as an unwarranted compliment to their rightie pundits. They may rise to mediocre only on their very best days. But as conservative pundits, they’re actually the cream of a very poor crop. The dearth of good conservative writers is something NYT, and the rest, should own up to.

@gVOR08: My garden is a disaster. So they are garden variety.

Manchin strikes me as a business owner who, like Trump, would be puzzled by such an observation. Many of them I’ve known over the years are firmly committed to the proposition that if it’s not illegal, there’s nothing wrong with doing it.

I was going to mention the Epipen (Mylan Labs – if there is a Manchin scandal, this is it) – but I could say similar about Paul Pelosi.

I see this NYT article as a political hit piece. How dare this hick stand in the way of NYC politics! I could easily write a piece with the same facts about how he is a environmental savior for getting rid of mountains of waste products using specially designed incinerators that also produce power = Co-Gen plants. Would you rather have piles of “gob”

I have friends in WV that use coal for home heating today. I’m guessing the rest of you don’t have friends in WV. My friend has a PhD, specializing in satellite communications. Nah, he is just a WV hick in your view. Flyover territory.

The governance of the most powerful country on Earth, the only habitable planet around but which is becoming less so by the minute because of fossil fuels, is currently being squeezed through the bottleneck that is a Joe Manchin, a fossil fuel advocate.