Making the Transition in Iraq and Afghanistan

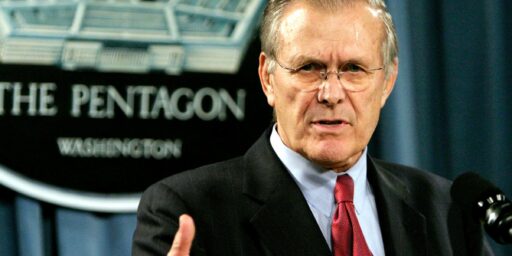

Yesterday’s New York Times featured a collection of seven columns on the challenges the incipient Obama Administration faces in managing the transition between administrations in two ongoing wars, in Iraq and Afghanistan. Contributors cover a wide spectrum of opinion and expertise from journalists (Linda Robinson, Rory Stewart) to scholars (Anthony Cordeman) to military officers (Peter Mansoor) to a former Secretary of Defense (Donald Rumsfeld) to a political operator (Ahmad Chalabi). There is something in the collection to hearten, concern, baffle, or infuriate practically everybody. For example, former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld opens his column by strenuously defending his own record on Iraq:

As one who is occasionally — and incorrectly — portrayed as an opponent of the surge in Iraq, I believe that while the surge has been effective in Iraq, we must also recognize the conditions that made it successful. President Bush’s bold decision to deploy additional troops to support a broader counterinsurgency strategy of securing and protecting the Iraqi people was clearly the right decision. More important, though, it was the right decision at the right time.

and closes by casting cold water on the idea of a surge strategy in Afghanistan:

The way forward in Afghanistan will need to reflect the current circumstances there — not the circumstances in Iraq two years ago. Additional troops in Afghanistan may be necessary, but they will not, by themselves, be sufficient to lead to the results we saw in Iraq. A similar confluence of events that contributed to success in Iraq does not appear to exist in Afghanistan.

What’s needed in Afghanistan is an Afghan solution, just as Iraqi solutions have contributed so fundamentally to progress in Iraq. And a surge, if it is to be successful, will need to be an Afghan surge.

Anthony Cordesman does something fairly rare in such anthologies in castigating another contributor:

Moreover, the best case for the Iraq war means coming to grips with the legacy of the worst secretary of defense in American history, Donald Rumsfeld. In spite of recent progress under Defense Secretary Robert Gates, Mr. Rumsfeld’s inability to manage any key aspect of defense modernization has left the Obama administration a legacy of unfunded and expensive new trade-offs between replacing combat-worn equipment, repairing and rehabilitating huge amounts of weapons and equipment, and supplying our forces with new, improved equipment.

His column is chock-full of insights—highly recommended.

Rory Stewart questions the prudence of current strategies in Afghanistan:

A sudden surge of foreign troops and cash will be unhelpful and unsustainable. It would take 20 successful years to match Pakistan’s economy, educational levels, government or judiciary — and Pakistan is still not stable. Nor, for that matter, are northeastern or northwestern India, despite that nation’s great economic and political successes.

Of the contributors Mr. Stewart’s views correspond most closely to my own.

Some of the pieces paint a rather rosy picture, like Frederick Kagan’s:

America and Iraq also have common interests vis-Ã -vis Iran. Iraqis want to remain independent of Tehran, as they have now demonstrated by signing the agreement with the United States over Iran’s vigorous objections. They want to avoid military conflict with Iran, and so does America. Iraqis share our fear that Iran may acquire nuclear weapons, which would threaten their independence. And they resent Iran’s efforts to maintain insurgent and terrorist cells that undermine their government.

Of course, the Iraqis recognize, as we do, that Iraq and Iran are natural trading partners and have a religious bond as majority Shiite. This may be to our benefit: the millions of Iranian pilgrims who will visit Iraqi holy sites at Najaf and Karbala over the coming years will take home a vision of a flourishing, peaceful, secular, religiously tolerant and democratic Muslim state.

One can only hope. Some, like Rory Stewart’s are, frankly, much more pessimistic.

I think that Anthony Cordesman’s assessment of Iraq is on target:

Even if the United States fully withdraws from Iraq in 2011, as Mr. Obama and the Iraqi government say they would like, we will remain on something very like a war footing there throughout the next presidency. While the combat burden on our forces will decline, withdrawal will be as costly as fighting. It will take large amounts of luck (and patient American prodding) for the Iraqi government to move toward real political accommodation while avoiding new explosions of ethnic and sectarian violence.

Even with progress on those fronts, we will have to withdraw while still helping to win a war, contain internal violence, limit Iranian influence and counter its nuclear program, create effective Iraqi security forces, and help Iraq improve its governance. Not a full war perhaps, but at least a quarter war in terms of continuing strains on our military and budget.

However unpalatable it is to reflexively isolationist Americans the only real recourse we have, both in Iraq and Afghanistan, is a commitment to a lengthy, in all likelihood permanent, engagement with both countries, indeed with the parts of the world that they’re in. The engagement will necessarily partially be military but it will mostly be non-military—diplomatic and economic. Maintaining this in the face of limited resources and pressing needs at home will be quite the challenge.