Robert Plant’s Second Act

Harvard's Jack Hamilton extols "Robert Plant's Second Act" for the Atlantic. In so doing, he gives us an interesting look at the more important First Act.

Harvard’s Jack Hamilton extols “Robert Plant’s Second Act” for the Atlantic. In so doing, he gives us an interesting look at the more important First Act.

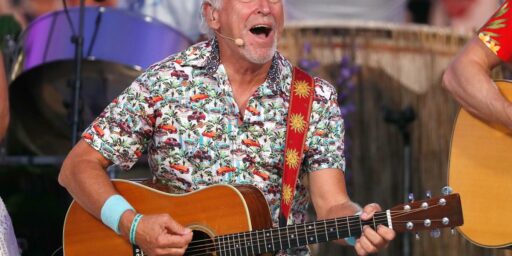

In late 2007 Rounder Records released Raising Sand, a collaboration between Plant and the sumptuously talented bluegrass musician Alison Krauss. Sparkling reviews and unexpectedly robust sales finally culminated in Raising Sand being awarded Album of the Year at the 2009 Grammys, and last month Plant released his own sequel of sorts, Band of Joy, a gorgeous, 12-track collection of far-flung cover songs rendered in his newfound wheelhouse of rootsy Americana.

Band of Joy isn’t just one of the better albums of 2010, it’s also probably the best music Plant has made since the 1970s, a valuation that includes the Krauss collaboration, which for all its charms had a slickness that sometimes felt overly cozy. Produced by guitarist Buddy Miller, Band of Joy is weirder than its predecessor and even more enchanting, a vision of musical Americana that feels lived-in without being nostalgic, refined without being precious. Making this renaissance all the more remarkable is Plant’s iconic association with Led Zeppelin, one of the most thrilling and significant bands in history and one whose relationship to American music—specifically African American music—was among the most troubling.

What follows is a strange lament that, because Zeppelin’s brand of hard rock was enjoyed disproportionately by white males, it was somehow a repudiation of the contributions of Hendrix. Whose music was enjoyed disproportionately by white males. It’s rather a stretch.

But this rings true:

Led Zeppelin’s catalog contains some of the most powerful moments in rock music, moments that push the sex/violence dichotomy to such extremes that it compels us on its own terms. “Good Times Bad Times,” the first track on 1969’s Led Zeppelin, is maybe the most outrageously aggressive opening track on a debut album in history, two-and-a-half minutes of unmitigated, bone-rattling purpose; for all its faux-orgasmic theatrics, “Whole Lotta Love” has a lowbrow eroticism that’s genuinely effective (and Zeppelin knew as well as anyone that sometimes lowbrow’s the most effective kind). And “When The Levee Breaks,” the closing track on their ambiguously-titled fourth album, is simply a masterpiece, one that reimagines Memphis Minnie’s flood blues with a churning, unrelenting terror that reaches toward the sublime—no rock band ever made music that sounded like this, and none have since.

I was a child during the band’s heyday, becoming aware of them around the time that they released Coda, their final real album. But they were doubtless a great band, and arguably the most important hard rock band.

This is, however, fairly apt:

Led Zeppelin’s blues cosmology was painfully literalist, all squeezed lemons, backdoor men and every-inch-of-my-love’s, an inclination that might go a long way towards explaining some of the band’s own lyrical deficiencies. “Let the music be your master / will you heed the master’s call?” from “Houses of the Holy” might be the single worst lyric ever written; every line of “Stairway to Heaven” is in an endless tie for second.

The piece’s close comes back to the racial theme:

Band of Joy finds him working entirely in this vein and its best performances, such as the rendition of Townes Van Zandt’s “Harm’s Swift Way,” are closer to the spirit of Ray Charles than anything Plant has ever sung. Nowhere is this more evident than in his carefully loving version of the gospel classic “Satan Your Kingdom Must Come Down,” a song it’s nearly impossible to imagine Led Zeppelin approaching subtly (see their eleven-minute version of “In My Time of Dying” for an idea).

In this sense, what’s most interesting about Robert Plant’s second act isn’t what it tells us about the continuing popularity of roots music, or even the state of Plant’s career, but rather what it tells us about Led Zeppelin, one of the most influential and continually confounding bands in all of rock and roll. The critic Robert Christgau once referred to Led Zeppelin as “genius dumb,” a funny and memorable appellation that manages to be both spot-on and not entirely fair. Led Zeppelin wasn’t dumb, they just weren’t quite as smart as they thought they were. By abandoning dubious fantasy and pretentious hysteria and learning to embrace his music on its own terms, Plant’s doing some of the finest work of his career. Heed the master’s call, indeed.

Now, while it’s hard to criticize the notion that Sounding More Like Ray Charles Is Good, the idea that white boys from the UK have some special duty to sound like a black man from Georgia is, to put it mildly, odd.

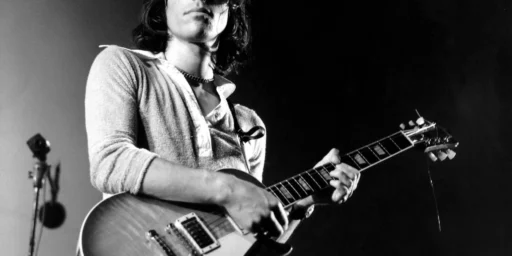

I heard an interesting story about Plant and Zepplin. When Jimmy Page was forming the band he was, of course, looking for a singer. At that time, Plant was fronting some skiffle band in the Midlands, but word of his talent got back to Page. As I recall the story, Page contacted Plant through a third party and was told that Plant thought he had a good gig going, after all he said, “I’m making about 5 pounds a week up here.” It took a little doing to get him to come to London to audition.

“every line of “Stairway to Heaven” is in an endless tie for second.” True enough, I suppose, but Stairway is probably Zepplin’s most popular piece. It’s the totality of the piece that brings it home. I don’t know that lyrics are all that important. Critics make a big deal of them, but I’m not sure we paid all that much attention them. (If lyrics were the foundation of rock music’s appeal, how explain Dylan? Not that he didn’t write some great lyrics, but a lot of his stuff has lyrics that, in truth, don’t make a hell of lot of sense.) Anyway, Plant came to hate Stairway to Heaven, but the band would play it at Live Aid. Plant said he couldn’t understand why people liked the song so much, but if they wanted it, the band would do it. Which only brought home to me the truth that the artist is the very last person you go to understand a piece of art.

What an oddly confounding denouncement of the group “most troubling” relationship with African-American music. Part of the point appears to be that the group heightened “Western associations” between black music, and sex and violence. I’d have to pull out my Howling Wolf albums and count, but I’m not sure any of his songs were not about sex or violence. Is Led Zeppelin to blame for rap?

I think that what was said obliquely and sometimes poetically at one point in time, has become more coarse and explicit. I think that defies issues of race.

Interesting post.

Some random observations:

– I share the lament about certain lyrics. But Stairway was always about the guitar lines and riffs, not the words. In addition, Plant has always said he thinks Kashmir is their masterpiece. I put it up there with “Time of Dying” – pretentious and overwrought.

– They often are criticized for ripping off bits and pieces of classic bluesmen’s lyrics and references. But I say they always twisted them into their own image. Its almost like saying bands ripped off 4/4 timing. The Stones ripped off plenty of black bluesman’s licks too, but retained the R&B flavor, and didn’t go metal with it.

– I’ve got a few years on you. Its a shame that CODA is your first memory. There was nothing quite like being a teenaged boy in the throws of hormonal chaos and putting that tonearm down on those first 3 Zep albums. I have made sure to get two sets of the vinyl releases (and vinyl IS better) just to satisfy those R&R urges from time to time.

– you mean that lemon thing wasn’t about childhood memories of setting up a lemonade stand? Huh.

– if you are really into the history, go get the complete set of Robert Johnson recordings. He only did something like 32 of them. But you’d be amazed how often you hear them in modern work.

sam –

When I lived in CT I happened upon Keith Richards a couple times. In one meeting I told him I thought “Start Me Up” was just a piece-of-crap song. Without disagreeing, he just quipped: “got to play the crowd pleasers, mate.”

Howlin’ Wolf loved the Stones, because they showed him respect. The Stones borrowed from the Wolf and the Wolf borrowed from Sonny Boy Williamson and so on.

I’m reading the Keith Richards book and one thing that is very clear is that the Stones had a reverence for guys like Wolf, Muddy, Robert Johnson etc…that borders on religious worship. I don’t think Zepellin was ever quite that grounded but all these English boys learned music from listening to old Chess records a thousand times over, learning riffs and phrasing.

Michael –

I don’t think ANYONE took to the classic blues guys like the Stones. And it was really Keith. Mick was very influenced by Cochran. If those early pre-British invasion/non-Beatles days interest you, I’d recommend you also read Ronnie Wood’s book. Combined with “Life” it brings into clarity all that London area interplay between Jagger, Richards, Rod Stewart, Woodie, Jeff Beck, Clapton, Ginger Baker, Page, JP Jones, Watts, Brian Jones, The Who and on it goes.

Its fascinating. They all knew each other from, oh, age 17. And it all got sorted out to our benefit. As Keith said, Mick, Charlie and I were the only ones who went out into the jungle and actually came back!

I think there were a few significant shifts here in a relatively short period of time. In the middle, I think the British Invasion groups were very attracted to the electric bluesmen, made albums with them or insisted they be booked to perform shows with them. Before the British invasion, you have the charges of appropriation of material, since performing a Negro song didn’t seem to come with any recognition or dough.

But I think for a lot of blues fans, the giants of Blues had been brought on stage for their final act in the sixties. And in some cases their collaborations with pop music had diluted their powers. So, it’s not entirely surprising that the Stones are seeking out and appearing with Howlin’ Wolf, while a later act like Led Zeppelin is mining and offering tribute to Robert Johnson. The gist is very similar, the personal expression differs.

BTW/ Drew, I liked that Rolling Stones article you referenced over at Dave’s place (I followed the link all the way through). It’s flabergasting that one of the (two?) biggest groups of the sixties says they weren’t making any money in the sixties. Only the Beatles made money.

And really their peak was in ’72.

I too love getting the Led out, grooving to the Stones — but no one has mentioned Eric Clapton or Jeff Beck yet and any discussion of English boys playing American blues music can be really complete without at least mentioning them. Even the Beatles were influenced by profoundly by American blues music. There was something about American blues music that all these kids from England in the late fifties and early sixties. (Which leads me to think that living in England during the late fifties and early sixties must have really sucked.)

Nor has anyone offered comment on whether Robert Plant’s recent exploration of American roots music is any good. I enjoyed Raising Sand and thought that Plant and Krauss’ voices were very interesting together. I’m very curious about Plant’s new work and frankly, I think all the business about race is a little bit silly. Yeah, the old-time singers were black, the boomer kids from England were all white, but isn’t the real question whether the music is good?

PD –

They admit to signing bad deals in the sixties. But they’ve made up for it. Estimates have both Mick and Keith at about $450MM in net worth. (each)

“I know, its only rock and roll but I like it………”