Rotten Way to Pick a President

Sean Wilentz and Julian Zelizer argue that the current system of primaries and caucuses is “A Rotten Way to Pick a President.”

Something is seriously wrong with the way we pick our presidential candidates. But experts and pundits, caught up in the horse races, have been slow to point out the obvious — or have come to accept our badly flawed system as immutable fact.

Actually, experts and pundits have been pointing out the flaws of the system for as long as I can remember. Indeed, the points Wilentz and Zelizer make are familiar to regular OTB readers — and pretty much anyone else who follows the process closely.

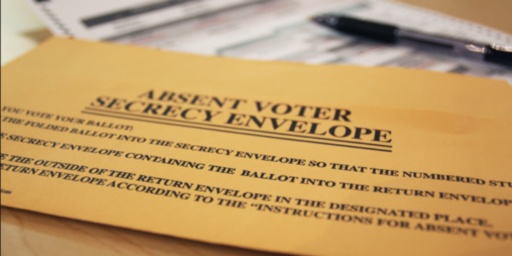

For one thing, caucuses can be highly undemocratic. They eliminate the secret ballot, forcing voters to declare their loyalties publicly, and are thus vulnerable to intimidation and manipulation. They also shut out many citizens who have to work during caucus times. If you can’t show up at a specific hour, you can’t vote — a particular problem for people with fixed shifts, including many of the working poor. (The supposedly democratic caucuses can also discriminate, as happened to Sabbath-observant Jews who couldn’t get to Nevada’s Saturday caucuses.) And there are usually no absentee ballots, of course.

The magnified importance of the early showdowns also opens the door to abuse. This year, Democrats in Michigan and Florida moved up their contests, thereby drawing the ire of the national party, which vowed not to seat the delegates. Unless something changes, voters in these states will be unfairly removed from the decision-making process, and neither candidate will benefit from their support.

“Open” primaries and caucuses (in which anyone can vote, not just registered party members) let voters from the other party cause all sorts of mischief. A Republican convinced that Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton is too divisive to win in the fall could vote for her in some Democratic contests in the spring, hoping to saddle the Democrats with a losing nominee. Or, as Sen. Barack Obama’s campaign did in Nevada, a candidate can openly appeal for votes from people outside his or her party in order to stop a rival. The winners are outsiders hoping to game the system; the losers are rank-and-file party members whose choices count less.

Another basic irony: Primaries tend to favor highly committed voters from the extremes of both parties, who are much more likely to turn up than moderates. So candidates have strong incentives to pander to their extremist flanks, throwing red meat that they may well regret in November or in the White House. For example, Reagan tacked far to the right during the 1980 primaries on abortion and other issues dear to religious conservatives, only to leave policies in these areas generally untouched after he won. Bill Clinton roused the Democratic base with populist themes during the 1992 primaries — only to govern as a moderate centrist as the realities of the federal deficit left from the Reagan and Bush years sank in. Over time, the necessity of flattering the base during the primary season — and of ignoring all that thunder in the fall — only intensifies the sense of outrage, alienation and cynicism that has dogged American politics for decades.

Finally, while the primary system took power away from the party barons, it gave much of that clout to the news media — now driven by national outlets that prefer sensationalism, scandal and sound bites to substance, nuance and balance. While retail politics survives in states such as New Hampshire, the real kingmakers today are the national media, which determine how most voters see the candidates. The seriousness of the candidates’ debates, in both the primaries and the general election, has nose-dived since the famous 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates — let alone the Lincoln-Douglas debates of exactly 150 years ago, when no journalists were onstage.

The problem, of course, is that there’s no easy fix for these issues. And some of the fixes they want to make are contradictory.

I’ve long been an advocate of a national primary to winnow both fields to two candidates followed by a run-off months later, allowing voters to narrow their focus to two candidates. I’m also four-square against open primaries, thinking that partisans should decide their party nominees. But these changes would probably strengthen, not eliminate, the power of the national media. Indeed, almost any system of selection that depends on voters is going to be filtered through the prism of media coverage.

Further, closed primaries would intensify the need to tack left or right to appeal to the party base. So you can’t simultaneously take independents out of the process and increase the likelihood of moderate nominees; they’re mutually exclusive goals.

It’s true that caucuses and any other system that eliminates absentee ballots disenfranchises those who can’t vote on a particular date or time. But there’s no solution that’s without tradeoffs. We could have Saturday voting, for example, but there’s the Jewish Sabbath issue. We could have continuous elections that go on for days or make absentee voting easier. But that increases the likelihood of fraud and can effectively disenfranchise those who vote for a candidate who drops out of the race between the start of balloting and the actual date of the election.

And I’m not sure what the fix for the Michigan and Florida problem would look like. Either we have no rules and we let states continually jockey for first place, wreaking havok with campaign strategies and making a mockery of the process or we have rules and enforce them.

Ultimately, there’s no perfect system. Having party bosses pick candidates rewards experience and mainstream appeal but is undemocratic; having voters decide invites pandering and demagoguery. Having a long, drawn out contest allows relative unknowns to emerge but taxes the patience of the electorate and is expensive; a national primary rewards those who begin with lots of money and/or name recognition. Letting party activists chose the nominees provides more choice on election day but lessens the likelihood of electing a consensus builder.

We’ve been tweaking the way we’ve elected our presidents since the early 1800s. No system we’ve yet hit on has seemed to be better than any other at producing “great” presidents or more than its fair share of duds.

I think the idea of a national primary, and then another run off is an interesting one.

I see two problems-one-will the candidates that aren’t the big money recievers early be able to realistically compete in a nationwide primary for the same day. Two-should the states be forced to pay for two primaries in the same year. Although, part of the answer for the second is to have the parties fund at least one if not both of the primary elections.

James, Michigan and Florida aren’t a problem for the American electoral system, they’re a problem for the DNC and IMO they’re only a problem because the DNC let them become one. There are a host of prospective solutions.

They could hold to their guns and continue to refuse to seat the delegates. They could cave and seat them. They could offer to seat all the delegates elected in a second primary. And so on.

But it’s an intra-party squabble not a general problem with the electoral system.

Dave,

I largely agree with you, but still favor some kind of reform. I thought the Democrats pretty much laid the ground work for this by making the penalty too harsh.

If they had done what the Republicans did and just cut their number of delegates in half, it wouldn’t look like they were trying to disenfranchise two entire states. It would be harder for candidates (Hillary) to argue for changing the penalty if it had been less harsh.

Robert

The problem isn’t the quality of the debates. It is the quality of the candidates and that means the quality of the voters who keep voting for, accepting, and enabling such poor quality leaders.

It’s like the fool that keeps buying one fifty cent flashlight after another and then curses them because they don’t work.