Scanning for Success

David Brooks [RSS] argues that manufacturing is actually thriving in the US:

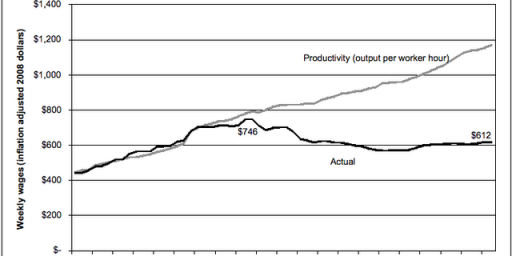

Since 1995, the U.S. has enjoyed a productivity renaissance. The McKinsey Global Institute breaks the economy down into 60 sectors. U.S. workers are the most productive on earth in at least 50 of them. Productivity gains cause standard of living increases. Productivity gains lead to employment gains. If history is any judge, yesterday’s excellent job numbers could mark the beginning of another surge in job creation.

As William W. Lewis, a former McKinsey partner, writes in “The Power of Productivity,” about half the U.S. productivity gains have occurred in just two sectors, wholesale and retail trade. We’ve gotten really efficient at getting stuff from the hands of manufacturers to the hands of consumers. These innovations have had more important effects on how people really live than anything done in Washington.

***

Over the next seven months, the politicos are going to argue about the economic merits of the Republican years versus the Democratic years. That’s a crime against intelligence.

The reality is that since about 1977, administrations from both parties have undertaken a series of policies, starting with deregulation, that have leveled the playing field and hence led to the period of intense business competition we enjoy today. That’s the environment that fosters innovation.

Yesterday’s good economic news — and the generally good news we’ve seen over the past 20 years — owes more to innovators like FedEx’s Fred Smith than to any of the many fellow Yalies who have sat or will sit in the Oval Office.

Which is, of course, true.

Matthew Yglesias counters,

But do we really think the reason the US has seen more GDP growth over the past twelve months than has, say, Chad is because our population is more innovative? Doesn’t it seem more likely that decades of superior policies are playing an important role here? Consider that 250 years ago, the gap between the US and the world average wasn’t really all that big. Now it’s huge. Did a lot of innovators just happen to show up here, or was government policy set up in a way so that the innate innovativeness of the people wound up doing some good.

Well, sure. But Brooks wouldn’t disagree with that. Our political and economic cultures grew out of the Enlightenment. It’s a happy coincidence that Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and our Declaration of Independence both came in 1776. We started out with a more-or-less clean slate, free of the baggage of aristocracy and the mercantilist tradition and, indeed, suspicious of both. Laissez faire economics has essentially always been taken as the presumptive starting point of our public policy.

It’s long been my contention that presidents can’t do much to fix the economy but they can certainly help derail it. While I’ve maintained that Bill Clinton gets far too much credit for the boom of the 1990s, his instinct to promote free trade abroad and to basically let the tech boom run its course without much interference almost certainly helped it last longer and get bigger than it would have under a more regulatory regime. George W. Bush, to my chagrin, is less ideological on that point and has been prone to make token protectionist measures in (a thankfully unrewarded) attempt to broaden his support base. Still, his instincts are generally toward deregulation and open competition.

While I’m sure Matt is being facetious with regard to the Chad comparison, it is of course the case that the reasonable point of comparison is with other highly developed states. While, certainly, the U.S. has been blessed vis-a-vis Western Europe with a much larger land mass and generally more abundant natural resources, it is our relatively open system that has largely explained our comparative success. It’s no accident that the society with less of a welfare state, lower taxes, and less regulation continues to pull ahead. The fact of the matter is that it’s simply much harder to be Fred Smith–let alone Bill Gates–in Europe than the U.S. Indeed, many a would-be

So, in essence, Brooks and Yglesias are both right. Our public policy choices have promoted innovation–but the public policy choice has been to leave people alone to innovate and to keep most of the rewards that come from the innovation.

As an aside, David Adesnik is worried that Brooks’ column will be interpreted as a criticism of Bush’s policies rather than simply a truism. My guess is no one who’s inclined to believe presidents actually create jobs actually reads the Times, since it lacks a comics section.