Security Data-Mining And Other Forms Of Witchcraft

At what point do science and magic converge? And what are the potential costs?

Yesterday, as part of an editorial in support of the NSA surveillance programs, the Wall Street Journal wrote:

From what we know, the NSA runs algorithms over the call log database, searching for suspicious patterns over time. The effectiveness of data-mining is proportional to the size of the sample, so the NSA must sweep broadly to learn what is normal and refine the deviations. […] We bow to no one in our desire to limit government power, but data-mining is less intrusive on individuals than routine airport security. The data sweep is worth it if it prevents terror attacks that would lead politicians to endorse far greater harm to civil liberties. [mb: emphasis mine]

As I read it, the author is saying that security data-mining promises that, by collecting enough data, and running the right algorithms on it, we will not just be able to catch terrorists after the fact, we will be able to predict what will occur and prevent it from happening.

This promise is nothing new. Science Fiction authors like Phillip K. Dick have been toying with the implications of this possibility for decades. In fact, this type of promise goes even further back. Thinking about it as an anthropologist, I see the promises we find in predictive, scientific technologies as being closely related to the promise that so-called “primitive” peoples placed in magic.

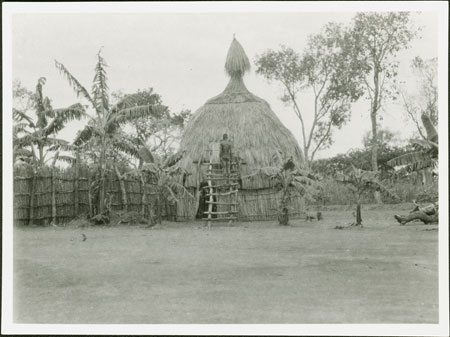

To paraphrase one of the most famous passages of E. E. Evans-Pritchard’s seminal ethnographic work Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic among the Azande, the Azande tribe in Southern Sudan use magic not to explain why a granary fell, but to explain why a granary fell on a particular person. The Azande understand all the practical reasons why a granary might fall: its old, rickety, termite infested, etc. They knew it was going to fall sooner or later. But what they cannot explain is why it picked a specific moment to fall. And why did it fall when one person was shading under it instead of when someone else was underneath it? That’s where magic comes in.

Evans-Pritchard writes:

To our minds the only relationship between these two independently caused facts [the granary collapsing due to old age, and it collapsing onto certain people shading beneath it] is their coincidence in time and space. We have no explanation of why the two chains of causation intersected at the certain time and in a certain place, for there is no interdependence between them. […]

Zande philosophy can supply the missing link. The Zande knows that the supports were undermined by termites and that people were sitting beneath the granary in order to escape the heat of the sun. But he knows besides why these two events occurred at a precisely similar moment in time and space. It was due to the action of witchcraft. If there had been no witchcraft people would have been sitting under the granary and it would not have fallen on them, or it would have collapsed but the people would not have been sheltering under it at the time. Witchcraft explains the coincidence of these two happenings.

Evans-Pritchard: Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic among the Azande. p69-70

The Azande believe that the reason the granary fell on those particular people, at that particular time, was because a witch cast a spell. For the Azande, and many other tribal people, magic becomes a way of explaining the radical contingency of life. And, to one degree or another, magic also enables the user to arm herself against contingency. Spells and charms are used to protect the wearer from other spells and charms — to ensure that the granary doesn’t fall on you.

The more and more I think about the promises of data-mining and security, the more and more I find myself thinking about magic. In particular, I keep returning to the Azande’s use of magic to connect and control seemingly random events in order to make the world a safer and less contradictory place.

For the western world, it’s harder to think of something more contradictory than an act of terror. On the one hand, acts of terror have a certain unpredictable randomness to them — why this year’s Boston Marathon or the Twin Towers on that particular day? At the same time, because the perpetrators are seen as part of larger networks of human activity, acts of terror also strikes us as something that should be entirely preventable – they only happen because of breakdowns in intelligence or policing.

Further, one can even argue that due to the spectacular and often symbolic nature of terrorist strikes in the West — often perpetrated against national targets or on days of significance — there is a certain “magical” aspect to them. Like a spell, the function of the terror strike is not only to attack the people at the scene, but the psyche of a nation — or social/ethnic group as a whole. It’s at once physical and metaphysical.

Hence we reach the promise of security data-mining: if we collect enough ingredients (data records) and if we say the right incantation over them (algorithm code), then we will be protected. Through magic, we can know when existential evil will strike; we can prevent the granary from falling upon us.

To be clear, in comparing the use of data-mining for security purposes to Azande magic, I’m not saying that data-mining isn’t an effective tool. There is significant evidence to suggest that it’s worked in the past. It’s a perfectly rational system.

That said, if you were to ask one of Evans-Pritchard’s Azande about the efficacy of magic, they’d produce evidence as well. That’s the think about systems, from an insider’s view they typically appear rational. Standing on the outside, you tend to see things a little differently. And that’s what we gain from thinking about security data-mining through the lens of magic: an outside perspective. It gives us an opportunity to think about some of the underlying reasons we are trading privacy for security – or rather the promise of security.

In other words, how much of our support for these activities is based out of a hope that they will protect us, rather than their actual ability to do so? And what are we paying into the system in return for that hope? Magic always has a cost.

Considering that the revelations about the NSA come the same week that the Supreme Court ruled that taking DNA samples is akin to taking a fingerprint, it seems to me a good time to pause and think. After all, how far separated are our phone, credit card, email and social media records from our DNA and fingerprints? They are all the marks we leave on the world. At what point does it begin to make sense to start scanning those records for evidence of other criminal acts? Consider the question Adam Weinstein asked last night:

Side note, obviously, but I guess I just wonder: If NSA has this massive capability, how are there still any child pornographers at large?

— Adam Weinstein (@AdamWeinstein) June 7, 2013

Update: Another parallel worth noting between magic and algorithms is that in both cases, much of their efficacy is based on secrecy. As Marcel Mauss points out in A General Theory of Magic, the reason a witch/sorcerer/warlock/shaman is needed is because they possess secret, expert knowledge necessary to make the spell work. The person availing themselves of the service is not able to always see the spell being cast. And even when the casting happens in front of people, there’s always something necessarily hidden from the participants. So everything hinges on one’s faith that they found a “real” shaman, versus a fraud (and most people acknowledge that there are only a few “real” shaman out there).

Likewise the algorithm is always secret. Even in the case of Google Search, it’s always about reverse engineering how it works. The rational is that we cannot learn about the inner workings of the security system because revealing those workings will undercut the entire system. Granted, when it comes to data-mining algorithms, the argument seems pretty cut and dry.

Still accepting that rational — to see it is to destroy its ability to protect us — also means that we are dealing with a black box and need to trust our experts that things are working correctly. And to some degree it moves away from the realm of scientific proof and back into a space of “faith.”

I think the reason government (and corps) build these petabyte databases is that at this point they are pretty cheap, and still awe-inspiring. Of course there must be magic in it, it’s a petabyte 😉

Matt,

Very good post/essay. Kills me to say it, but at least the WSJ is being consistent. Unlike a certain gelatinous congresscritter from Wisconsin. Apparently, Dr. Franken-brenner isn’t a fan of the monster he created, and is now joining the villagers by picking up a torch and pitchfork. Bit late for that, Doc.

Because the NSA is a national security agency which collects information pursuant to national security, and not law enforcement. Information collection for national security purposes requires a significantly lower burden of proof before a judge (e.g., the FISA court), and quite probability wouldn’t meet the Fourth Amendment requirements for a criminal prosecution.

Further, while child pornography is repugnant, the NSA has no desire to give up its methods and means to prosecute it.

I think the problem is not that data mining doesn’t work. Then it would be easy to get rid of it.

The problem is that does, and we can rationally show it does. It may not have 100 per cent predictive power: but its better than nothing, so we have to continue with it.

Isn’t there an Arthur C. Clarke quote to the effect that any sufficiently advanced technology will appear to be magic to the uninitiated?

One does have to wonder if all this big data isn’t more bureaucratic ass covering and security theater than it is real security.

@Timothy Watson: Exactly. Once the rocket goes up, who cares where it comes down, child pornography’s not my department says Werner Von Braun.

@stonetools:

Data mining for suspect identification doesn’t have to work to get funding, it just needs a good “elevator pitch.” As in “we need to develop methods, and we need to start now …”

As I say though, I’m more worried about the panopticon aspect. Sure, Verizon and Visa could get together and produce a “week in the life of John Personna,” but we know they have no interest in that. They just care about “what can we sell John Personna?” That’s less dangerous to me. Indeed, what I buy might make me happy.

On the other hand, Verizon and Visa might produce a “week in the life” report for 3rd parties. Do we have any blocks on that kind of thing?

@john personna:

According to the DNI, data mining did help foil several plots.(The usual problem here is that if he detailed how it was done, it would tip off future terrorists as what not to do).

I am clearer that these surveillance techniques do help us catch the offenders quicker. The Boston bombers might have gotten away absent the the massive coordinated surveillance state response.

@Timothy Watson:

You’re completely right… for the moment.

However the issue is that once these data repositories exist and are seen as having the ability to prevent bad things from happening and help bring bad people to justice, other groups start to want to have access to them.

Again, that’s why I bring in the issue of the Supreme Court and the DNA decision. All it takes to be compelled to give over one’s DNA is an arrest. It’s not hard to envision a path to this information being handed out under similar circumstances.

All in the name of protecting the public, of course.

My understanding is that, in addition to helping ferret out the participants in the terrorist network (see the first season of The Wire for how it works with a drug network) it’s also really good for dealing with the problem of burner phones and other means of losing surveillance. That is, is Abu changes phones, they can pretty easily find him again by looking for people calling the people Abu was calling on the old phone.

@john personna & @stonetools:

BTW, here we get into another interesting parallel between magic and algorithms:

In both cases, much of the efficacy is based on secrecy. As Mauss points out, the reason a witch/sorcerer/warlock/shaman is needed is because they possess the secret knowledge necessary to make the spell work. Likewise a key rational is that we cannot learn about the inner workings of the security system because revealing those workings will undercut the entire system.

Granted, when it comes to data-mining algorithms, the argument makes more sense. But it also means that we are dealing with a black box and need to trust our experts that things are working correctly.

@stonetools:

I am speaking more generally. Database X did not need to produce answers to get funded.

And the set of funded databases surely exceeds the set of successful databases.

@stonetools:

And this get’s back to Adam Weinstein’s question… If these tools work so well at capturing terrorists, why don’t we apply them to catching regular criminals?

See the evolution from fingerprints to DNA in bringing cold cases back to life.

@Matt Bernius:

So you are asking for the panopticon, and for it to be made available to say 10,000 local detectives?

@john personna:

No. I’m playing devils advocate and reminding people that once upon a time DNA evidence was used only is the most special of cases.

I’m of the opinion that, regardless of efficacy, there is going to be a big push to take these tools and apply them in civil law enforcement in the same way that once “military only” tools like drones are now being deployed in the US.

And I, personally, think that a lot of that push has to do with a collective belief in the “magical” promise of these technologies rather than a rational understanding of their strengths and limitations.

@Matt Bernius:

OK. I guess we have similar concerns, but different worries. I’m worried about how easy things are, things that don’t require magic at all.

As I said in a recent thread, it used to be that the FBI would need to get a warrant to put a GPS tracker on your car to follow your movements. When a location history is now commercial metadata from a cell phone provider, it is just easy to track people.

Have laws responded, or have government agencies just glided in with commercial purchasers?

“From what we know, the NSA runs algorithms over the call log database… ”

From what we know. It all hinges on that. The program is secret. The court is secret. There is no oversight of which the public is aware. The underlying data is right there, so tantalizingly close, just a few bits to the right.

Forgive me if I do not automatically buy the claim of “meta-data only” simply because someone from our lovely government says so.

Stories like this will drive the deployment of secure networks that span our growing always-on overlapping clouds, and bypass the ISP where all this nonsense has to occur.

I think the key to the legality of these programs is contained in DNI Clapper’s statement last night:

They have all the information gathered, but nobody is allowed to look at it unless they’re looking because of “a reasonable suspicion, based on specific facts.” Collection is broad, but inspection is stringently limited.

The fear–which is far from unfounded–is that having the huge pool of information will inevitably create a temptation to use it for all sorts of purposes unrelated to national security.

I think what we’re left with, then, is to accept “privacy” as we’ve understood it for the last couple hundred years is for all intents and purposes dead, and now we must ensure the strictest oversight of whoever wishes to access the massive amount of information we now know the government is capable of collecting.

@Mikey:

So say you are the FBI, and I am Blackwater. You might be proscribed from doing certain things with data, where I am not. On the other hand, you might be able to purchase an “electronic security report” from me. What happens next?

@Mikey:

Actually there’s another fear that’s less discussed. The very fact that this poll is seen as having national security value makes it a potential target. As, Matt Frost (@mattfrost) pointed out last night:

“Nice of the NSA to create a one-stop shop for any foreign service good enough to crack it.”

What are the chances that China or another power might have already accessed part, if not all, of the current data repository?

The very nature of digital objects is that they move towards abundance, not scarcity.

@john personna: Well, I think the first step is to prevent that happening in the first place. I mean, I’m a contractor and I’m not permitted to do anything with data that my government customer is prohibited from doing, because the only way I access that data is through methods derived from them.

@john personna:

Pretty sure there are laws prohibiting the use of classified data like that. .

@Matt Bernius: As far as the chances of some foreign entity “cracking” access to this stuff, I really don’t have much insight except to say it would likely be an “inside” job. I know the existence of programs like PRISM imply a direct connection between the commercial entities and the NSA, but my experience tells me that’s not the case, and there are safeguards I’m not even going to start discussing. Suffice it to say if we’ve thought of it, the guys at Ft. Meade thought of it years ago.

@Matt Bernius:

I’m sure China is trying to break into the NSA’s stuff, and the NSA is trying to get into China’s stuff. May the best encryption algorithm win:-).

I know people who have worked with intelligence folks that they say the key computers aren’t connected to the Internet. Some aren’t networked at all.They’re in a room, and only certain people have the keys.

Sorry Matt…it’s nice to see you posting for OTB…but this is pure bunk.

There is absolutely no parallel between algorithms and witchcraft.

Algorithms actually work and have been used for nearly a century to acheive real accomplishments.

Witchcraft is…well…witchcraft.

Algorithms are used for calculation, data processing, and automated reasoning.

Witchcraft is used to explain the un-explainable to people who need an explanation, any explanation, to quell their insecurities. (see also; the bible)

The observer effect is also real…and affects things as simple as checking the air in your tires…to as unexplainable as quantum physics.

I anxiously look forward to your post on witchcraft and the quantum Zeno effect.

@stonetools:

But these key computers will be connected to the Internet even if it’s not direct connection. How is data copied to these computers and how is it copied from them, ending up in a computer with direct Internet access?

The question is, can the Chinese, etc find a way to piggy back through the kind of connection there is?

@PJ:

Ever heard of “Sneakernet?”

@john personna: “As I say though, I’m more worried about the panopticon aspect. Sure, Verizon and Visa could get together and produce a “week in the life of John Personna,” but we know they have no interest in that. They just care about “what can we sell John Personna?” That’s less dangerous to me. Indeed, what I buy might make me happy.

On the other hand, Verizon and Visa might produce a “week in the life” report for 3rd parties. Do we have any blocks on that kind of thing? ”

I think that this view is mid/late 20th century; it assumes that this sort of report is not ‘produced’ literally in milliseconds at the click of a mouse. Or that these reports are not being produced and updated continuously.

@stonetools: “According to the DNI, data mining did help foil several plots.(The usual problem here is that if he detailed how it was done, it would tip off future terrorists as what not to do).”

And found the Iraqi WMD’s?

@Mikey: “Well, I think the first step is to prevent that happening in the first place. I mean, I’m a contractor and I’m not permitted to do anything with data that my government customer is prohibited from doing, because the only way I access that data is through methods derived from them. ”

John’s point is that many laws restricting ‘government agency’ activities can be bypassed by using contractors.

@Matt Bernius: The point of the Surveillance State is not to stop terrorists, but to have lots of useful data on hand with which to skewer anyone who becomes a person of interest, for any reason. We’ll see a bill authorizing the use of databases belonging to the intelligence community for identifying, tracking and prosecuting other accused criminals. It’s only a matter of time.

@Barry:

And my point is we need to make sure the government isn’t permitted to offload those restricted activities to contractors. If the government isn’t permitted to look at a piece of collected data, contractors at ABC Company must not be allowed, either.

interesting take from Yglesias…

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2013/06/07/us_tech_giants_have_many_foreign_customers.html

@Barry:

I certainly know that they can happen in milliseconds, as stored procedures, if you will. The question is whether framing them as old-world “contracting for research” makes them legal.

@all:

It may be that I’m wrong and many managers and lawyers at Google, Apple, Runkeeper, and etc. are all requiring that government dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’ for their requests, and acting as stewards of privacy laws .. but the broad feel I’ve gotten over the last 10 years is that privacy constraints are gradually breaking down. Companies seem to give government a little more data, each year. Increasing access becomes the norm. YMMV.

@Sam Malone:

First, thanks for the response. Especially since it gives me an opportunity to clarify a few points.

To be clear, I don’t think science = magic.

But I do think there are a number of important parallels, especially when you look at both as social forces. And I think a lot of non-science people tend to treat science as if it has certain magical powers (that’s part of what I’m expressing above).

They do work. But any good Com Sci person will quickly also admit that there are a lot of situations in which they *DO NOT* work particularly well. Especially when you get towards the fringes of data sets.

Additionally, since algorithms are coded by *people* they also tend to have encoded biases and blind spots. However the very nature of them being algorithms, and therefore “science”, tends to make them appear far more objective than they necessarily are.

Which gets us

Comparisons like this hinge upon a hard myth/science understanding that doesn’t necessarily hold up in all cases. Looking at most oracles, we find simple binary choice machines. And yes, in some cases their results are relatively random, but in other cases the success of the magic has far more to do with a practioners ability to read and diagnose her subject.

Likewise, when one looks at medical diagnostic technologies, we find that they work great on a large amount of the population, but often fail in cases where diagnosis requires sifting through data that machines are not particularly good at working with.

All that aside, again, returning to the WSJ article I started by quoting, I again suggest that the faith the author places in algorithms is more of an irrational religious/magical faith than a scientifically grounded understanding.

Again, I’m all good with making technology and policy decisions based on a ground understanding of both the strengths AND the limitations of any scientific system.

However, I think it’s a fundamental mistake to assume that just because a system is scientific it (a) doesn’t contain a lot of subjective biases, and (b) isn’t being thought of in essentially magical ways by many policy makers (not to mention the general public).

Science is without a doubt, the best system we have for understanding the universe. But it’s also a system, that by design, should recognize it’s limitations and work within them. Cultural history proves that things don’t always work that way.

Re. algorithms … the government saying “they worked and we found terrorists” is a little like a day trader saying “they worked and I made money.”

Neither claim describes the total statistical reliability of the algorithm. Neither categorizes the rate of false positives, or false negatives. Neither describes the fragility of the algorithm with changing conditions.

@john personna:

This. This. A thousand times this.

And it speaks to the question of why and how do we trust algorithms. And what work do we expect them to do? Especially in cases where it’s difficult to work in immediate human intervention.

Remember the day in 2010 when an algorithm gone wild crashed the market? Or more recently a tweet combined with an algorithm had a similiar effect?

Again, in both cases systems performed in unexpected ways due to aspects of the code that had unintended effects. Again, this isn’t to say scrap the system. Rather its to remind us to question why and how we put our faith into such a system (and again, just as with magic, ask what are the costs).

It’s…WITCHCRAFT!

@Mikey:

And here I thought Monty Python would be the first you tube link from this thread.

@Matt Bernius: It’s a fair cop…

@Matt:

Good post.

@this:

So what, can you describe for me a privacy line that has been defined and then held over the last 10 years?

That would certainly seem to be the sort of 3rd party I suspected.