Speaking of the Economy…

...and the perceptions thereof.

I already had this piece from The Atlantic, Why Americans Can’t Accept the Good Economic News, opened in a tab to finish reading, and after James Joyner’s post about grocery prices, it seemed worth nothing.

The piece notes the following.

First, median household net worth is up.

The rise in median household net worth was the most notable improvement: It jumped by 37 percent from 2019 to 2022, rising to $192,000. (All numbers are adjusted for inflation.) Americans in every income bracket saw substantial gains, with the biggest gains registered by people in the middle and upper-middle brackets, which suggests that a slight narrowing of wealth inequality occurred during this time. In particular, Black and Latino households saw their median net worth rise faster than white households did—though the racial wealth gap is so wide that it narrowed only slightly as a result of this change.

A big driver of this increase was the rising value of people’s homes—and a higher percentage of Americans owned homes in 2022 than did in 2019.

Of course, if most of that is the value of one’s home that doesn’t increase your purchasing power. In fact, the main function in the short term is that your property taxes go up. But the piece notes that it is more than that.

households’ financial position improved in other ways too. The amount of money that the median household had in bank accounts and retirement accounts rose substantially. The percentage of Americans owning stocks directly (that is, not in retirement accounts) jumped by more than a third, from about 15 to 21 percent. The percentage of Americans with retirement accounts went from 50.5 to 54.3 percent, a notable improvement. And a fifth of Americans reported owning a business, the highest proportion since the survey began in its current form (in 1989).

Debt burden has improved:

Americans also reduced their debt loads during the pandemic. The median credit-card balance dropped by 14 percent, and the share of people with car loans fell. More significantly still, Americans’ median debt-to-asset, debt-to-income, and debt-payment-to-income ratios all fell, meaning that U.S. households had lower debt burdens, on average, in 2022 than they’d had three years earlier.

Income is up.

The gains in real income (in this case, measured from 2018 to 2021) were small—median household income rose 3 percent, with every income bracket seeing gains. But that was better than one might have expected, given that this period included a pandemic-induced recession and only a single year of recovery.

[…]

Hourly wages for production and nonsupervisory workers (who make up about 80 percent of the American workforce) rose 4.4 percent year-on-year in the third quarter of 2023, for instance, ahead of the pace of inflation. And this was not anomalous: Arindrajit Dube, an economist at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, crunched the numbers and found that real wages for that same sector of workers are not just higher than they were in 2019, but are now roughly where they would have been if we’d continued on the upward pre-pandemic trend.

The piece concludes thusly.

So, even allowing for the high inflation we saw in 2022, no one could really look at the U.S. economy today and say that the policy choices of the past three years made us poorer. Yet that, of course, is precisely how many Americans feel.

Although that pessimism does not bode well for Biden’s reelection prospects, the real problem with it is even more far-reaching: If voters think that policies that helped them actually hurt them, that makes it much less likely that politicians will embrace similar policies in the future. The U.S. got a lot right in its macroeconomic approach over the past three years. Too bad that voters think it got so much wrong.

As the piece notes: we, as a country, are in much better shape than we had any right to expect after the pandemic. But, of course, people do not assess their personal feelings about the economy based on macroeconomic indicators. Ultimately, the reality remains, as is James’ ongoing thesis, that people pay a lot more attention to grocery and, especially, gas prices when assessing their views of the economy.

By the same token, I paid $2.75 per gallon for gas at Costco on Thursday (and I noted the Walmart price was $2.79), but I am betting that that will not turn the state of Alabama towards Biden, or even cause folks to shake the general feeling that the country is in bad shape economically. By the same token, beef prices continue to be much higher than a few years ago. I am, luckily, at a point in my life where I look at the price, note it, and still purchase what I want, but that the price is higher is still pretty stark.

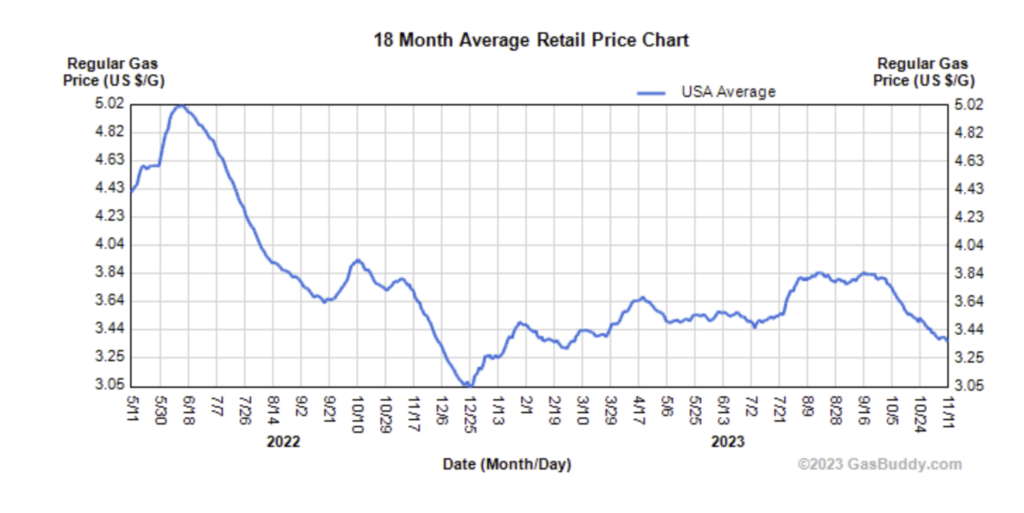

FWIW, here’s the gas price trend over the last 18 months via GasBuddy.

Well, gas is still pretty high here in Nevada and neighboring California, so I’m afraid I’m going to have no choice but to vote for a criminal fascist imbecile.

My little town is experiencing the first gas war I’ve seen in about 40 years. Regional prices range from a high of $4.799 to a low of $3.749. It started when Marathon and Sinclair entered the market and decided to sell gas at about 50 cents below the prevailing market rate. They’re still both selling at about 40 or 50 cents below the prevailing competition and each lowers its pump price in response to drops in the other’s.

Thinking of Sinclair, I guess right wing nut jobs are good for something after all. We’ll see.

Only weirdos like us read econ statistics. Real people vote on feels.

As there are econ nerds here, we should note the gas price chart appears to be nominal, not inflation corrected, dollars.

Something is slightly askew here… If the median went up, and the largest gains were in the middle and above-middle quintiles, that pretty much has to mean that the bottom quintile fell relative to the median, even if it gained in absolute terms. That’s not a decrease in effective wealth disparity, even if the bottom quartile gained on the top quartile.

Don’t get me wrong — this is all good news, and better than I had looked for. And gains in the middle are good for exiting recession. Long term, though, we really need for the bottom quartile to grow faster than everyone else for an extended period.

@gVOR10: This is the only general commentary place on the internet where I wouldn’t be surprised to see animated discussion of the relative merits of chained versus unchained price indices, or when it’s more appropriate to use GDP vs. CPI deflators for policy analysis…

The problem with macroeconomic indicators is that aggregate statistics hide all the variability once one starts to de-aggregate what’s going on. I don’t think it’s just gas and groceries.

For example, here is the real median household income percentage change between 2021 and 2022 for each state (2023 stats aren’t available yet, obviously). I could not figure out how to show this from 2019-2022. Idaho was the worst state at -12.5%, and Delaware was the best at +9%. That’s a big difference just on a state level.

And in terms of the 2024 election and the battleground states that will likely decide the contest, it’s a mixed bag when looking at real incomes.

Point being, the story – and the probable political effects for 2024 – quickly get more complicated once one starts drilling down with more precision.

Gawd, I wish us Brits had it as “bad” as you Yanks

UK inflation: 7%.

Unemployment: 4.3%

Economic growth: sod all (to use the technical term)

If you lot don’t like Joe Biden, can we have him?

“I could not figure out how to show this from 2019-2022. Idaho was the worst state at -12.5%, and Delaware was the best at +9%. That’s a big difference just on a state level.”

There is always wide variability between states. As keeps being pointed out, that doesnt seem to matter. People have bought into the ideas that inflation is well ahead of income and the economy is worse.As has been pointed out elsewhere, people on fixed incomes are being hurt because health care costs increase faster than COLA increases, but that is always the case.

Steve

@gVOR10: Over short-term nominal dollars is appropriate. Real “econ nerds” do not willy-nilly deflate short-term nominal pricing. One generally applies deflators over longer multi-year periods (assuming normal single digit inflation, etc). 18 months as nominal given rate of income change and timing is not per se problematic.

@steve: It is not “people have bought into” – rather a broad spread of the population, particularly those on lower wage scale pay – working class in general, experienced a near-term hit which they may or may not have recovered on from a Net Basis point of view. Insofar as unlike the Uni educated professional salaried classes, such segments have been under longer-term economic stress with lower average gains in income, near-term hits to them are certainly felt disproportionally (this magnified by the cognitive bias in loss-aversion that makes loss felt rather more intensely than gain).

Nothing unusual in this, it is utterly typical of populations being hit with inflation spikes.

Taking “false conscioiusness” narratives is engaging in self-deception.

@JohnSF: Bonjour Brexit. Sunny uplands. Swashbuckling.

@Andy: to understand differential impacts it is profitable to consider the differential impact of inflation spike on different income / economic class segments. It is not only an issue of fixed-income, there is a baseline of how such economic class segments have experienced economic / income growth as well.

If you look at decomposed data for income gains over past decades, people of the uni intello-professional classes (as represented here) have done on macro level [this aggregate so of course the various inevitable personal anectdates that will be posted are not data] rather better than what we can call working classes for short-hand, or let one say the bottom 50% (not merely “working poor”) – an effect that should not be decoupled from MAGA…

Already economically stressed, it would not be in the least surprising given what is well known from behavioural economics about loss-aversion and overweightings (in pure numeric terms) in perceived value to see a strong reaction to up-front immediate losses from unexpected inflation which they are typically slowest to recover from (and may not have yet on net-net basis although at current patterns should in near term).

@Lounsbury:

While not an econ nerd, this makes sense to me. “Prices have remained steady if we adjust for inflation” is rather batty. Inflation, after all, is prices going up!

@Lounsbury:

Based on my recent experiences working in the social safety net space, this is 100% the case. I think we also need to include the further context that we are now 3+ years into an incredibly stressful period for most hourly workers–especially those close to/at/or below the poverty line.

The closer you get to that line, the more unstable your finances become–especially because our social safety net is sadly designed to be a last resort versus a stabilizer. As a result being just above poverty is and incredibly difficult place to be because you often cannot access the safety net because you earn just a bit too much. That leaves you especially vulnerable to inflation and incredibly attentive to it.

To Lonsberry’s point, that also means you have a (well-grounded) confirmation bias that any increase in price is a net negative for you.

“, near-term hits to them are certainly felt disproportionally (this magnified by the cognitive bias in loss-aversion that makes loss felt rather more intensely than gain).”

Much better stated than I did.

Steve

Unseen is the rise in “mortgage” payments if they include property taxes and insurance in escrow. The latter homeowner insurance is rising rapidly on the inflation of rebuild costs. I recently had to tell a family member they were falling behind because they were paying the mortgage payment as when the loan was taken out but hadn’t realized the $100/mo increase that they found out was due to insurance cost rising when they call their loan servicer.

I’ve also seen more layoffs from the unprofitable tech sector, as well as slow hiring. This is impacting the “social media managers” which are mostly women more. Or all as Jezebel recently laid off everyone. That will cause issues for Democrats among the single, college-cred women they depend on. Not unlike when companies dependent on the kindness of strangers, i.e., new investor money, in 1999, suddenly found the spigots had been turned off. Elon Musk was ahead of this when he got rid of 75% of Twitter’s staff, those not producing code.

Only this time, it is happening when easy money is drying up as retiring Boomers, those born in ’58 turn 65 this year, move their money to less volatile or speculative investments. Millennials are in their household formation years so spending for consumer goods, but savings thin. Learning to cook for the kids to save money on eating out, much less DoorDash. Cancelling those online subs that chew up the monthly budget.

@James Joyner: Really the idea is that over shorter terms say less than a year or maybe year and half (as like 18 months), income changes (salary rises given by employers and the like) generally are lagging price rises and so the nominal change is roughly reflecting a real reality experience in shorter term.

@Matt Bernius: I make the broader observation that the Democratic party has become somewhat blinded to how its “base” (to use a term I dislike rather strongly) – that is its most engaged activist party partisans have a significant bias – geographical and economical as you have trended to being a Univeristy educated professional class dominated party, and one rather heavily urbane urban centric (as it is expressed in French Intello BoBo, intellectual bohemian bourgeouisie for a certain kind of Left). Whose overreach can have Thermidorien result if care is not taken.

It should be said that my observation was aimed not merely at a working poor profile you evoke but the broader reach on “working class” in labour terms that has seen over the past two decades in much of developed markets a relative stagnation of income and erosion of status (again this reaches back to MAGA also, one should not ignore the economic links of stress into the political reaction). That tie in is a source of danger if the Democrats autistically adopt a pitch based on their Intello-BoBo base view and experience.