Supreme Court Guts Clean Water Act

A 5-4 ruling overturns a unanimous decision from 1985.

WaPo (“How Supreme Court’s EPA ruling will affect U.S. wetlands, clean water“):

Bogs. Marshes. Swamps. Fens. All are examples of wetlands.

But the type of wetland that gets protection under federal law is a matter of wide dispute, one reset by a sweeping ruling Thursday from the U.S. Supreme Court.

At issue is the reach of the 51-year-old Clean Water Act and how courts should determine what count as “waters of the United States” under that law. Nearly two decades ago, the court ruled that wetlands are protected by the Clean Water Act if they have a “significant nexus” to regulated waters.

The Supreme Court decided that rule no longer applies and said the Environmental Protection Agency’s interpretation of its powers went too far, giving it regulatory power beyond what Congress had authorized. Here’s what you need to know about the ruling.

Writing for five justices of the court, Justice Samuel A. Alito ruled that the Clean Water Act extends only to “those wetlands with a continuous surface connection to bodies that are ‘waters of the United States’ in their own right, so that they are ‘indistinguishable’ from those waters.” He was joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil M. Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett.

[…]

All of the justices thought the EPA got it wrong regarding the couple who brought the case — Michael and Chantell Sackett, who want to build a home on their property near one of Idaho’s largest waterways, Priest Lake.

But the justices disagreed on other particulars.

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh took issue with the majority’s ruling that the EPA lacks authority to regulate wetlands that “are separated from a covered water” by a dike, levee or other barrier.

“The Court concludes that wetlands in that second category are not covered as adjacent wetlands because those wetlands do not have a continuous surface connection to a covered water — in other words, those wetlands are not adjoining the covered water,” he wrote. “I disagree because the statutory text (‘adjacent’) does not require a continuous surface connection between those wetlands and covered waters.”

[…]

Some environmentalists and legal experts say it could limit the EPA from acting on many modern problems, especially climate change, or doing anything that might expand the authority of a federal agency beyond previous limits. They point to language from Alito requiring Congress to “enact exceedingly clear language” on rules that may affect private property. They further point to trends in the court’s rulings and the cases it is agreeing to take that suggest the conservative-majority court is skeptical of the executive branch’s regulatory power.

“No environmental rule is safe in the wake of this decision,” said Patrick Parenteau, an environmental law expert at Vermont Law School.

But others say the ruling is not that expansive. There are major differences between the Clean Water Act and other bedrock environmental laws in the parameters they set around federal authority, said Kevin Minoli, a partner at the Alston & Bird law firm and former lawyer in the EPA’s Office of General Counsel under Republican and Democratic administrations. That probably limits the influence Thursday’s decision may have on attempts to regulation air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions and chemicals.

“I do not see the Supreme Court’s decision as an imminent threat to environmental regulations adopted in other contexts,” Minoli said.

In a companion op-ed (“The Supreme Court just gutted the Clean Water Act. It could be devastating.“) Harvard Law professor Richard J. Lazarus is scathing:

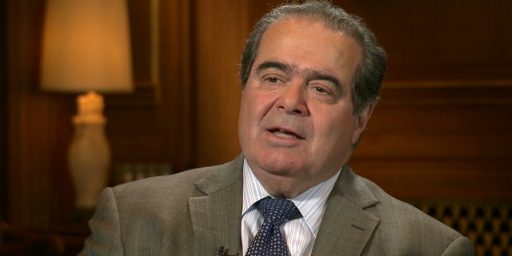

Justice Antonin Scalia died more than seven years ago, but the Supreme Court’s decision in Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency on Thursday shows that this is the “Scalia Court” far more so than when he was alive.

The ruling arrives almost a year after the court’s conservative majority made the worst fears of environmentalists a reality in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, which severely curtailed the ability of the nation’s environmental laws to protect public health and welfare. The Sackett ruling doubled down on that disregard for pollution and public health, and the effect will likely be devastating.

The precise legal issue decided in Sackettconcerns the geographic scope of the 1972 Clean Water Act. Congress intended the law to end the practice of the nation’s waterways being used as the unregulated dumping ground for industrial pollution. The effect was transformational: For the first time in the nation’s history, any discharge of pollutants into the nation’s waterways absent a permit was unlawful, making it possible to safely fish and swim waters throughout the country.

Congress was not at all shy about the geographic reach of the Clean Water Act. The statute targeted discharges into “navigable waters,” but Congress also expressly defined that to include all “waters of the United States.” Since the mid-1970s, the courts have uniformly agreed that Congress intended with that expansive definition to extend the law’s protections far beyond traditional navigable waters to include the wetlands, intermittent streams and other tributaries that feed into the nation’s major rivers and lakes.

In a unanimous opinion for the court almost 40 years ago, Justice Byron White explained why. While acknowledging that “on a purely linguistic level, it may appear unreasonable to classify ‘lands’ wet or otherwise as ‘waters,’” the court said “such a simplistic response … does justice neither to the problem faced by the [government] nor to the realities of the problem of water pollution that the Clean Water Act was intended to combat.”

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr.’s opinion in Sackett, however,embraces the very “simplistic response” that the court rightly criticized in 1985. Relying on a dictionary definition of “waters” and ignoring the Clean Water Act’s purpose, the court’s conservative majority has adopted a radically truncated view of the reach of the law’s restriction on water pollution. Under the court’s new view, pollution requires a permit only if it is discharged into waters that are “relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water, ‘forming geographic[al] features’ that are described in ordinary parlance as ‘streams … oceans, rivers, and lakes.’” And “wetlands” are covered only if they are “indistinguishably part” of those narrowly defined covered waters.

This is exactly what Scalia wanted to accomplish in 2006 when the Clean Water Act was last before the court. He managed to cobble together three other votes to gut the law but fell one justice short. Now, with six conservative justices — three of whom are largely modeled after Scalia — Alito was able to accomplish what Scalia never could by securing the necessary fifth vote.

The impact of the majority ruling is potentially enormous. It could lead to the removal of millions of miles of streams and millions of acres of wetlands from the law’s direct protection. Basic protections necessary to ensure clean, healthy water for human consumption and enjoyment will be lost. As highlighted by Justice Elena Kagan’s separate opinion, the court’s opinion “prevents the EPA from keeping our country’s waters clean by regulating adjacent wetlands.”

Nor will the nation’s economy be spared. Myriad businesses rely on clean water for their industrial processes. The fishing, real estate and tourism industries are all highly dependent on the protections that the Clean Water Act has provided over the past half-century.

None of this was compelled by law. Even Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh rejected Alito’s majority view, announcing that he “would stick to the text.” Congress spoke clearly in the Clean Water Act about its ambitions and backed that intent up with deliberately sweeping language to provide the EPA with the discretionary authority it needed to realize those goals. Our nation’s waters are far cleaner as a result. Yet, for the second time in less than a year, an activist Supreme Court has deployed the false label of “separation of powers” to deny the other two branches the legal tools they require to safeguard the public.

Scalia might have been pleased. Our nation should not be.

I am far from an expert on environmental policy or what Congress intended by the phrase “waters of the United States.” One could, I suppose, argue that the Supreme Court should view statutes narrowly and then let Congress remedy the ruling by passing new statutes. The obvious counter is that, for the last two decades or so, Congress has been virtually non-functional. While I could preach that either way, the fact that Congress has let an incredibly expansive—and unanimous!—SCOTUS interpretation stand since 1985 would seem like a pretty strong indicator that it was the correct interpretation of legislative intent. (Especially since it came during the Reagan administration with a Republican-majority Senate and a much less sorted partisan atmosphere and we’ve had multiple periods with a Republican President and Republican majorities in both Houses since.)

Beyond that, for a Court ostensibly fighting to preserve its legitimacy and constantly railing about the lack of public deference for its rulings, they seem to be going out of their way to thumb their nose at longstanding precedent—the lifeblood of a Common Law system. While I’m agnostic on United States v. Riverside Bayview and think Roe v. Wade was incorrectly decided, they were rightly considered settled law after decades on the books.

This particular ruling seems to be yet another step in trying to dismantle the so-called Administrative State. I’m actually quite sympathetic to the notion that Congress delegating so much quasi-legislative power to Executive branch bureaucracies violates the letter and spirit of the Constitution. But, even while the Framers were alive, the Supreme Court issued common sense rulings that balanced the 1787 text with the practicalities of governance. There’s simply no way to run a 21st Century continental superpower without bureaucratic experts having significant regulatory flexibility.

Again, I suppose, the rote answer is “Amend the Constitution using the provisions of Article V.” Realistically, though, that’s essentially impossible.

Just as in recent Second Amendment cases, the court is flagrantly disregarding plain and clear English language in order to overturn legitimate legislation from the bench. In this case the majority opinion states that waters that are “next to” major bodies are not “adjacent” but instead must be continuous with that major body of water. This is an absurd reading of the definition of that word and goes against every dictionary entry. A body of water that is continuous with a major body of water is part of that major body and not adjacent to it. By including the “adjacent” language Congress clearly meant it to apply to bodies of water that are, well, adjacent to those major bodies.

And James, while I understand where you are coming from here, I think it is a dangerous way to look at legislation

Another way of looking at this: “If Congress passes a law and then changes its makeup, but not sufficiently to overturn the law, the Supreme Court is free to overturn it themselves to suit their political biases and then point to Congressional inaction in restoring it as proof that they were correct.”

This is what the Federalist Society was founded for. Its funders have only a passing interest in guns and abortion, motivated by a need to elect Republicans. That Koch Industries can now dump waste in wetlands next to, but somehow not “adjacent” to, important bodies of water is what really matters.

Who has given the courts the right to second-guess what the legislature meant with a certain piece of legislation? After all, we’re not talking about constitutionality (legislative overreach) here.

I guess that conservatives believe that originalism can go out the window – but only if it leads to “small government.”

That’s certainly a novel legal theory.

@MarkedMan: In the 1984 case, SCOTUS ruled that the Corps of Engineers was “reasonable” in interpreting “waters of the United States” to include wetlands even though there was nothing in the CWA indicating that intent. Basically, the doctrine in operation was that courts should defer to the expertise of regulatory agencies absent compelling evidence that it violated Congressional intent.

Again, I can preach that either way. But Congress has a remedy at hand if it disagrees: amend the law to clarify a narrower intent.

I don’t know how else statutory interpretation could work.

@drj:

That’s literally the job of courts. Congress writes laws that regulatory agencies and others than enforce. Who the hell else would adjudicate disputes over the interpretation? We can’t very well have Congress do it. Of course it’s going to be the judiciary.

@James Joyner: My understanding though, is that they majority opinion pretended they didn’t overturn this decision, but rather that the word “adjacent” meant something other than it did. They overturned it without having the balls to admit what they were doing.

That said, I misinterpreted your comment above. I thought you were saying, well, the opposite of what you were saying. Apologies.

@James Joyner:

Dude…

Courts adjudicate disputes when existing statutes conflict. They don’t get to say what statutes mean in the absence of any such conflict.

With which other statute does the CWA conflict?

My God, think just for a second about the implication of what you are saying. Your theory would render the legislative branch entirely impotent.

This is why Harlan Crowe’s lap dog sits on the SC.

@drj:

It is not and never has been the case, that the Court solely settles conflicts between statutes. Rather, it is more likely than not adjudicating the meaning of a given word or phrase in a statute.

While the previous interpretation was way too broad (under that definition, the peak of Mt. Hood could be covered as a “wetland”), this goes too far in the other direction.

I think the minority in this case had it right. I’m all for reigning in administrative agencies a little bit–not abolished, just reigned in a little. Under the 2015 EPA rule (and expanded upon in an EPA rule from this January), essentially all land in the US is considered a “wetland”[1], and it’s up to the land owner to convince the EPA that it isn’t.

The EPA took a reasonable law and decided “it means whatever we want it to mean”. The Clean Water Act is a good law, and should be enforced. But it needs to be done in a way that involves clear and reasonable definitions of what it covers, and how it’s enforced.

The EPA went too expansive, and now SCOTUS has gone too far in the other direction.

Congress needs to step in and clear it up. Unfortunately, as Dr. Joyner stated above, Congress can’t agree on the color of the sky, much less important legislation regarding the environment.

=========

[1]

Holland & Knight Law Firm

@Steven L. Taylor:

When there can be reasonable uncertainty over the meaning of the statutory text, sure. For instance when it gets applied to a situation that the original legislators didn’t foresee.

But black-letter law (what is what we are talking about here) should only get overturned by a court when there is a conflict with another statute.

For 45 years, it was clear what “adjacent” meant in the CWA. Since then, nothing changed except the make-up of SCOTUS. No new situation or new interests that would require rebalancing.

Now imagine the implications if a court can simply redefine what a statute says.

@drj: Look, I am not arguing anything, one way of the other about this ruling (but I will say that I am not in favor). But I am telling you straight-up that your understanding of what the courts do is just wrong.

As a general matter, words are open to interpretation (something I can assure you is true both in terms of what I write on this site for years as well as what I find, all the time, in my day job). This is especially true about statutes (which are rarely as straightforward as one might like).

It is constantly true that everyone who applied them, including bureaucrats, is interpreting. And when those interpretations come into conflict that the courts often step in. It just is the way it works.

I don’t have to imagine. It is the essence of what courts do.

@drj:

Alexander Hamilton begs to differ. From Federalist 78:

“The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts.”

@Steven L. Taylor:

This. Read the decisions handed down by the SCOTUS so far this term. The majority of them are answering questions as to whether a particular entity falls into a particular statutory or picky judicial category. In fact, that’s what this EPA case was about: did the wetlands in question fall into a category where the EPA had jurisdiction.

The vote on that question was 9-0: four that the wetlands didn’t meet the statutory definition of adjacent, five that said the statutory language about adjacency didn’t matter, the EPA’s authority ended at any point where there was not a free-flowing surface water connection. Two of those five went even farther. Their definition of “waters of the United States” was based on cargo-carrying ability and would exclude, for example, the Colorado River and anything in the Great Basin.

An alternative view is that the US Supreme Court has breathed new life in to Magna Carta and more specifically the companion document, Charter of the Forest.

That words are open to some amount of interpretation, doesn’t mean that they are open to any amount of interpretation.

Specifically, “adjacent” ≠ “continuous.”

Even if there isn’t a single, universally applicable definition of “adjacent” (or any word for that matter), that doesn’t mean that we can’t tell when the meaning of a word gets twisted beyond what it can reasonably mean.

To draw a parallel: sometimes it’s hard to distinguish between orange and brown. But some shades are definitely one and not the other.

It’s kind of childish to look at your typical orange carrot and argue that the thing might as well be brown, because there is no clear, well-established line between the two colors.

Narrowing or expanding language to fit one’s ideological preferences beyond any reasonable interpretation is not the essence of what courts do. What courts can do is to strike or reinterpret clear language that conflicts with another statute, or to clarify language that – for one reason or another – lacked or started lacking sufficient unambiguity.

Will be a while before I can read this but wife said this was a2part decision? One party was a 9-0 vote and other was 5-4. What was 9-0?

Steve

@James Joyner:

In the context of judicial review, i.e., when there are doubts as to the constitutionality of a piece of legislation. Hamilton:

Nowhere is Hamilton saying (IMO) that the courts may effectively change legislation post facto in the absence of a statutory conflict or lack of clarity.

(And it would be crazy if courts would have that right.)

@James Joyner:

“But Congress has a remedy at hand if it disagrees: amend the law to clarify a narrower intent.”

This assumes good faith on the part of the Supreme Court, that they will actually accept the actions of Congress based upon clear language in the statute. As cases like this one, and the voting rights act cases, have shown, that is a faulty assumption.

@Steve:

Whether the CWA applied in this particular case. All judges said it didn’t.

Even so, the majority felt that the CWA needed some additional gutting.

@drj:

This is incorrect. The definition of “waters of the United States” has been redefined (more expansively) at least twice–once in 2015 and again 4 months ago–along with some tweaks by both the EPA and the Army Corp of Engineers in 1986 and 1988.

ETA: The “Waters of the United States” isn’t defined in the statute, so it is impossible for there to be a clear definition of what is “adjacent” to them.

Is Federalist 78 part of the Constitution now? I can’t keep up with “originalist/textualist” goalpost-moving by Federalist Society hacks. A true originalist would point out that judicial review is not mentioned in but only maybe implied by the text of the Constitution. But throwing out Marbury v. Madison would probably be a bridge too far even for this unhinged, extremist, illegitimate Apartheid Court (probably?), as that would kneecap their ability to impose their ultra-conservative, papist ideology on the whole country. Hopefully there’s a cutoff year for gutting longstanding precedent.

@Mu Yixiao:

Sackett v. EPA overruled the clear language of the 1977 amendment of the CWA. See, e.g., Kavanaugh’s dissent. That’s 45 years.

@drj:

And since then the definitions of what it covers have been changed twice, so it has not remain unchanged for 45 years. The latest change was 4 months ago.

@drj: It has been the province of Common Law system judges, going back to before the Mayflower sailed, to interpret statutory meaning. And that role has only amplified under the administrative state, as Congress has left it to agencies (in this case, the EPA and Corps of Engineers) to fill out the details. It would be absurd if entities had no way to challenge bizarre interpretations of statutory language.

@DK: The Federalist is our best, if imperfect, guide to the intent of the Framers. It should be read for what it is—a set of propaganda documents arguing for ratification and thus downplaying the potential harms of the intended changes from the status quo—but we don’t have anything better to go on.

There was quite a long time when I believed that Marbury v Madison’s declaration of the power of SCOTUS to strike down acts it saw unconstitutional was suspect. But, not only did Hamilton all but spell it out in Federalist 78, it was actually a well-understood Common Law principle that the Framers would have been familiar with.

@James Joyner:

We do: The Constitution of the United States.

But I’m not opposed to jurists using whatever extra-Constructional sources and documents (and best-guess assumptions thereto) to bolster their conclusions. I’m opposed to them pissing on my leg and telling me they’re “textualist” and “originalist” or whatever code they’re using for rightwing judicial activism on any given day.

The framers would have been familiar with the common practice of allowing abortion up until the point of viability, a cutoff known way back then as “the quickening.” But that didn’t stop Alito from blatantly lying about that history in his messy Dobbs screed.

@James Joyner:

Bizarre in regard to original legislative intent or other statutory language, no?

In this case, SCOTUS took it upon itself not to clarify but effectively change clear legislative intent after the fact. Moreover, in the absence of any statutory conflict that could warrant such a move.

That’s not how judicial review is supposed to work.

I guess all that complaining about “activist judges” I’ve heard so much of over the years was an expression of jealousy.

And here I thought they wanted conservative principles, things like stare decisis and leaving earlier unanimous decisions alone.

Silly me.

@Mu Yixiao:

You should learn the difference between primary (statutes) and secondary (regulation) legislation.

Sackett overruled primary legislation, an Act of Congress, dating back to 1977.

@drj:

You should stop moving the goal posts.

No. It wasn’t. First of all, it wasn’t clear what “Waters of the United States” meant–since it was never defined in the legislation. The legislation only refers to “navigable waters, including US territorial seas”. It was in 1986 and 1988 that the EPA and ACoE made up their own definitions of WOTUS. They changed that definition in 2015–including what “adjacent” meant–to essentially cover 99% of the land in the US.

SCOTUS has redefined the meaning twice since 1977–in United States v. Riverside Bayview Homes, Inc (1985) and Rapanos v United States (2006). The fact that it made it to the High Court twice in that time (three times including this week’s decision) is a pretty good indicator that it’s not clearly defined.

@JKB: WOW! A source from 1215. A new record!

@Jay L Gischer: The only principle in politics (and policy at large for that matter) is win by whatever means are necessary.

We can split hairs about the role of the courts till the cows come home. This time might be better spent thinking about how to protect our utterly critical wetlands from decimation. In the face of climate change driven extreme weather and sea level rise, wetlands are probably more important than ever – and that’s saying something.

@anjin-san: Your comment reminds me of reading an account by an explorer in the New World who described the forests as so teeming with game that all the hunters in the world would never be out of game to hunt. We realize now that he was being hyperbolic (and I don’t even hunt), but this type of account is the stuff that has driven the American mind set forever. The only thing Americans have ever consistently preserved is vegetables for consumption over the winter and money–and relatively little of either of those.

We, figuratively, have paved paradise to put up a parking lot and won’t know what we’ve got til it’s gone, and even Joni Mitchell bought an Escalade in the turn of the millennium. We’re not really very good at long term. We’re a culture of grasshoppers. And winter is coming.

United States v. Riverside Bayview Homes, Inc (1985) and Rapanos v United States (2006) were not overturned were they? And please cite the 99% of US land that can be called wetlands.

I agree with Kavanaugh on this. The 9-0 made sense. The 5-4 doesn’t.

@The Q:

In Sackett v EPA? Yes, they were. Both Riverside and Rapanos allowed for a more expansive interpretation of the CWA than a “plain text” interpretation. Sackett essentially tossed both of them under the bus.

A) “99%” is a placeholder for “pretty much everything”. It’s not a literal percentage.

B) I cited it a couple of times earlier in the thread. The 2015 rule by the EPA bases its interpretation of “wetland” and “WOTUS” on the idea that any water that might eventually end up in a navigable waterway is covered by the WPA. It’s based on the Obama-era concept of a “single ecological unit” (See 88 Fed. Reg. at 3006-07) and the previously SCOTUS-defined “significant nexus”.

These theories state, in essence, that any water which might eventually end up in a navigable waterway (the only areas specifically specified in the actual legislation), falls under the jurisdiction of “adjacent”. The EPA interpreted that to mean “Anywhere that rain or snow might fall is covered by the CWA”.

The EPA insisted that they had jurisdiction over the land owned by the Sacketts because there was a ditch on the property–which–when it filled–fed into a creek, which fed into a lake.

The Sacketts filled in the ditch (which meant it would no longer feed into anything). With dirt.

The “wetlands” was a ditch. The “pollutant” was dirt.

SCOTUS unanimously decided that the EPA overstepped its authority and jurisdiction.