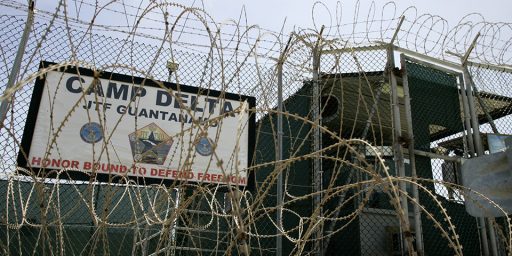

Supreme Court Denies Gitmo Habeas Appeals

The Supreme Court has denied a request from Guantanamo detainees who wish to challenge their confinement.

The Supreme Court rejected an appeal Monday from who want challenge their five-year-long confinement in court, a victory for the Bush administration’s legal strategy in its fight against terrorism.

The victory may be only temporary, however. The high court twice previously has extended legal protections to prisoners at the U.S. naval base in Cuba. These individuals were seized as potential terrorists following the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks and only 10 have been charged with a crime.

Despite the earlier rulings, none of the roughly 385 detainees has yet had a hearing in a civilian court challenging his detention because the administration has moved aggressively to limit the legal rights of prisoners it has labeled as enemy combatants.

Lyle Denniston provides trenchant analysis:

The practical results, so far as the detainees are concerned, are that (1) they no longer have any right to file a habeas challenge to their detention or to their designation as enemy combatants because Congress has taken that away and the lower court ruling that the Court left undisturbed Monday upheld that withdrawal, (2) those not charged with war crimes must now go through a military-only review of their enemy combatant status in proceedings that the detainees’ lawyers consider seriously inadequate; some had had that review, but there is a question whether another is to be held for most of them, (3) those charged with war crimes must now go through trials before new “military comissions” with procedures also widely attacked as inadequate and can go further only if convicted, (4) and detainees in both groups, after going through those two processes, have only a limited right to challenge their detention status or their military commission convictions in the D.C. Circuit Court, with possible later review by the Supreme Court — a process that, in its entirety, could take months, and maybe longer.

It’s a legally correct ruling, I think, in that Congress clearly has the authority under the Constitution to limit habeas during times of emergency as it sees fit. (Art. I, Sec. 9, Clause 2: “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”)

FindLaw’s Annotated Constitution, as always, is an invaluable guide to the history of judicial interpretation of such vaguely worded provisions:

Only the Federal Government and not the States, it has been held obliquely, is limited by the clause. 1688 The issue that has always excited critical attention is the authority in which the clause places the power to determine whether the circumstances warrant suspension of the privilege of the Writ. 1689 The clause itself does not specify, and while most of the clauses of 9 are directed at Congress not all of them are. 1690 At the Convention, the first proposal of a suspending authority expressly vested ”in the legislature” the suspending power, 1691 but the author of this proposal did not retain this language when the matter was taken up, 1692 the present language then being adopted. 1693 Nevertheless, Congress’ power to suspend was assumed in early commentary 1694 and stated in dictum by the Court. 1695 President Lincoln suspended the privilege on his own motion in the early Civil War period, 1696 but this met with such opposition 1697 that he sought and received congressional authorization. 1698 Three other suspensions were subsequently ordered on the basis of more or less express authorizations from Congress. 1699

Footnotes below the fold.

I continue to be concerned about the political implications of allowing the Executive to designate people for indefinite detention.

The story’s new. More commentary from the blogosphere will no doubt be chronicled at Memeorandum.

—

[Footnote 1688] Gasquet v. Lapeyre, 242 U.S. 367, 369 (1917).

[Footnote 1689] In form, of course, clause 2 is a limitation of power, not a grant of power, and is in addition placed in a section of limitations. It might be argued, therefore, that the power to suspend lies elsewhere and that this clause limits that authority. This argument is opposed by the little authority there is on the subject. 3 M. Farrand, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (New Haven: 1937), 213 (Luther Martin); Ex parte Merryman, 17 Fed. Cas. 144, 148 (No. 9487), (C.C.D. Md. 1861); but cf. 3 J. Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Washington: 2d ed. 1836), 464 (Edmund Randolph). At the Convention, Gouverneur Morris proposed the language of the present clause: the first section of the clause, down to ”unless” was adopted unanimously, but the second part, qualifying the prohibition on suspension was adopted over the opposition of three States. 2 M. Farrand, op. cit., 438. It would hardly have been meaningful for those States opposing any power to suspend to vote against this language if the power to suspend were conferred elsewhere.

[Footnote 1690] Cf. Clauses 7, 8.

[Footnote 1691] 2 M. Farrand, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (New Haven: rev. ed. 1937), 341.

[Footnote 1692] Id., 438.

[Footnote 1693] Ibid.

[Footnote 1694] 3 J. Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (Boston: 1833), 1336.

[Footnote 1695] Ex parte Bollman, 8 U.S. (4 Cr.) 75, 101 (1807).

[Footnote 1696] Cf. J. Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln (Urbana: rev. ed. 1951), 118-139.

[Footnote 1697] Including a finding by Chief Justice Taney on circuit that the President’s action was invalid. Ex parte Merryman, 17 Fed. Cas. 144 (No. 9487) (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

[Footnote 1698] Act of March 3, 1863, 1, 12 Stat. 755. See Sellery, Lincoln’s Suspension of Habeas Corpus as Viewed by Congress, 1 U. Wis. History Bull. 213 (1907).

[Footnote 1699] The privilege of the Writ was suspended in nine counties in South Carolina in order to combat the Ku Klux Klan, pursuant to Act of April 20, 1871, 4, 17 Stat. 14. It was suspended in the Philippines in 1905, pursuant to the Act of July 1, 1902, 5, 32 Stat. 692. Cf. Fisher v. Baker, 203 U.S. 174 (1906). Finally, it was suspended in Hawaii during World War II, pursuant to a section of the Hawaiian Organic Act, 67, 31 Stat. 153 (1900). Cf. Duncan v. Kahanamoku, 327 U.S. 304 (1946). For the problem of de facto suspension through manipulation of the jurisdiction of the federal courts, see infra, discussion under Article III.

Yeah, all those German soldiers we held during WWII had the same concern. NONE of them got trials and all and were held indefinitely until their country was defeated.

I think all POWs should get trials under civilian courts so other countries will like us better. The the world be a better place because it is all about making sure other people like us.

I think all POWs should get trials under civilian courts so other countries will like us better.

The Administration has steadfastly refused to treat these people as EPWs and apply that set of rules to them.

JJ neglects to notice that the Suspension Clause says nothing about “emergency,” just “rebellion” or “invasion.”

Leaving aside the dubious notion that 9/11 was an “invasion,” it would scarcely be an ongoing invasion.

Dennison’s post gives a better analysis — the Court is going to wait and see how the appeals under the MCA fare in the D.C. Circuit.

While this is unfortunate, given that (as Breyer noted) that circuit has already rejected any habeas rights for the Gitmo prisoners, it’s a predictable move — Kennedy is clearly on the fence, and wants to see how the MCA’s procedures play out.

I wonder if the new congress will see fit to rescind the law that stripped these people of habeas rights.

What country are we currently fighting?