The Filibuster Isn’t The Problem

It's undemocratic and we should get rid of it. But doing so isn't a panacea.

Political scientists Frances E. Lee and James M. Curry, of Princeton and Utah, respectively, argue that eliminating the filibuster wouldn’t matter as much as you’d think in advancing the Democratic agenda. How so?

The bigger obstacle to any party’s agenda is its members’ inability to agree among themselves.

We compiled the stated policy goals of every congressional majority party from 1985 through 2018. We identified the parties’ agendas by looking to the bills designated as leadership priorities and the issues flagged by the speaker of the House and the Senate majority leader in their opening speech to Congress, yielding a list on average of 15 top priorities per congressional term. Tracking each proposal, 265 in total, we found that the parties failed outright on their agenda priorities about half the time, meaning that no legislation on the issue was enacted.

We then analyzed when, how, and why each failed, and also whether the majority party faced a unified or divided government when it did. Naturally, when a party controlled the House, Senate, and presidency, it fared somewhat better in enacting its agenda than when it didn’t, but not markedly so. Parties failed on 43 percent of their agenda priorities in unified government as compared with 49 percent in divided government. This failure rate varies from Congress to Congress, but has remained fairly consistent even in recent years. When Democrats most recently held all three branches of government (in 2009-10), they failed on 50 percent of their agenda items. When Republicans most recently held all three (in 2017-18), they failed on 36 percent.

When a party has unified control of government, the filibuster provides the Senate’s minority party (if it has at least 41 senators) with the ability to stop the majority’s legislative efforts. This is why partisans focus so much on the filibuster, and why progressive activists are so concerned over it right now. But the filibuster accounted for only about one-third of the majority party’s failures during the periods of unified government we studied. In the two most recent instances of unified government—the Democrats in 2009-10 and the Republicans in 2017-18—agenda failures caused by the filibuster were even less common. The Democrats had just one of their priorities, immigration reform, fail because of the filibuster. The Republicans had none. Filibuster reform, then, may enable Democrats to achieve particular policy goals opposed by Republicans, and those would certainly be victories. But most failures, about two-thirds overall during years of unified government and 90 percent during the past two instances of unified government, stemmed from disagreements within the majority party rather than the minority party’s ability to block legislation via the filibuster.

While initially counterintuitive, it makes sense when you think about it. It’s relatively rare for a single party to gain control of all three levers at a time (albeit mostly because of inherent rural state advantages in the electoral system). When it happens, it will naturally require bringing more disagreement into the coalition.

In fact, every party that has had unified control of government in the post-Reagan era, as the Democrats do now, has failed on at least one of its highest policy priorities because of the party’s inability to reach internal consensus.

Newly returned to unified government for the first time since 1980, Democrats under President Bill Clinton collapsed on health-care reform, their top agenda item. The party deadlocked between moderates and liberals who could not agree on fundamentals, including an employer mandate and premium caps. Health-care reform never received a vote in either the House or the Senate in 1993-94. In 2003-04, Republicans could not agree among themselves to make the Bush tax cuts permanent; conservatives insisted that tax cuts pay for themselves, and moderates were concerned about deficits. In 2005-06, Republicans tried to add individual investment accounts to Social Security. But neither House nor Senate Republicans ever got a bill out of committee.

Okay, but we know things have ratcheted up to ridiculous levels under Mitch McConnell and company. So, how about more recent history?

During the Obama administration, which had periods of unified and divided government, Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell used the filibuster aggressively to block the president’s nominations. But filibusters of nominees do not tell us about the filibuster’s impact on lawmaking. Other analysts have shown that the number of filed cloture petitions (a motion that precedes “cloture,” or ending debate, requiring 60 senators in support) increased exponentially during McConnell’s years as Republican leader. They point to this number as evidence of the power of the filibuster. But the act of filing for cloture does not mean that a bill is actively being filibustered, only that the Senate’s majority leader wants to be ready, just in case it is.

For our analysis, we looked into the parties’ legislative efforts on their agenda priorities, drawing on journalistic coverage and several interviews with key players to ascertain why failures occurred. We found that filibusters were the cause of failure on only about one-third of the Democrats’ failed agenda items during the Obama years, and on just one of six failed items when the Democrats controlled both the House and Senate in 2009-10. This tally even includes instances in which news reporting indicated that the Democrats dropped a legislative drive in anticipation of a Senate filibuster. By contrast, almost 60 percent of failures during the Obama years were attributable to disagreements within the party.

How so?

For instance, in 2009-10, Senate Democrats never came close to passing a climate-change bill. Because of internal disagreements, the 2009 cap-and-trade bill passed the House of Representatives only with the help of a few Republican votes. But differences among Democrats then doomed the bill in the Senate, as lawmakers from oil-drilling and coal-mining states never got on board. Likewise, Democrats were unable to coalesce to repeal the “midnight regulations” adopted in the waning months of the Bush presidency. Democrats also failed to unify around a new direction in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and, after internal dissention, wound up passing military appropriations with overwhelming support from Republicans that continued operations with no significant change.

Okay. But Democrats have been notoriously disorganized going back to Will Rogers’ days. The Republicans are way more lockstep in their party discipline, right?

Republicans in recent years have also seen many of their party’s legislative ambitions fail, but rarely because of the filibuster. In the most recent case of Republican unified control (2017-18), during the first two years of President Donald Trump’s term, every case of failure in our data was due to disagreements within the GOP. Republicans could not agree on how to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. Despite devoting nine months to the effort, Republicans were unable to overcome their differences, even on the “skinny repeal” bill, which three moderate Republican senators—Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, and John McCain of Arizona—decisively rejected.

I blame Joe Manchin.

Although both parties have grown more cohesive in roll-call voting since the 1970s, they continue to struggle with intra-party disunity when it really counts. For instance, Republicans could agree on dozens of symbolic votes to repeal the ACA, but they were unable to do so when their votes would have had consequences in the real world. Turning vague campaign promises into actual legislative language is much harder than agreeing on messaging bills and other symbolic exercises.

Indeed, some argue that the real reason so many Senators in both parties (but especially the GOP) oppose eliminating the filibuster is because it would remove the ability to blame the other party for the failure of legislative initiatives that many in their own party simply don’t support.

Regardless, the current emphasis is on getting the Biden agenda passed before a possible Republican takeover of one or both Houses in the midterms. But Lee and Curry caution,

The Democratic Party in Congress today is less ideologically diverse than the Democratic Party of the Obama years. But it is also far smaller. A tiny number of dissenting votes is enough right now to deny the party its ability to pass anything by majority vote. In the Senate, Democrats can’t afford even one “no” vote, and we are already seeing signs of disunity. Consider the Biden administration’s $2 trillion infrastructure proposal, which has met opposition, not just from Republicans but also from moderate and progressive Democrats. Progressives have called the proposal “not nearly enough,” urging the Biden administration to “go BIG” and backing a $10 trillion plan called the THRIVE Act. Moderate Democrats are either concerned that the proposal is too big or oppose the full extent of the corporate tax hike—or both. Eliminating the filibuster will not bridge these divides.

By and large, they add,

Majority parties need to be large and highly cohesive to deliver on a partisan agenda—and these two conditions seldom coincide. For many reasons beyond the filibuster, including disagreements within each party caucus, differences between House members and senators of the same party, and the frequency of divided government, bills rarely become law on the strength of only one party’s votes. According to our calculations, since 2011, 90 percent of all new laws clearing the House, and 75 percent clearing the Senate, have initially passed the chamber with positive votes from at least a majority of minority-party members. Many of the bills that have gone on to become law have been written in a bipartisan manner from the start, even in the very majoritarian House of Representatives. Bills are often shaped in ways to get to at least 60 votes. Such efforts may involve painful compromises that can fracture intra-party consensus. But purposeful bipartisanship stems not from the filibuster alone. It is rooted in a constitutional policy-making system that obstructs party power in numerous ways.

Interestingly, they add, the system is less broken than it appears:

During President Barack Obama’s tenure, Democrats and Republicans also accomplished some major policy making together, including an expansion of the Violence Against Women Act, a revamp of federal K-12 education policy, the 21st Century Cures Act (which, among other things, streamlined drug-approval processes in ways that may have helped speed up the release of the COVID-19 vaccines), and the USA Freedom Act, which rolled back many of the unpopular surveillance policies put in place under the PATRIOT Act.

Congress does not need to get rid of the filibuster to do big things, nor will its elimination clear the way for a sweeping progressive agenda. Filibuster reform may make the opposition to the majority party’s agenda less potent, but it would do nothing to resolve the party’s continuing, significant internal disagreements. Internal diversity in two continent-wide political parties makes it very difficult for either to legislate its activists’ dreams into realities, filibuster or no.

While I’m not as enthusiastic as my co-blogger Steven Taylor, I’ve largely come around to his view that we should eliminate—or at least seriously weaken—the filibuster on sheer grounds of democratic principle. The system is already skewed too much toward rural/conservative/Republican interests in proportion to their distribution in the American polity.

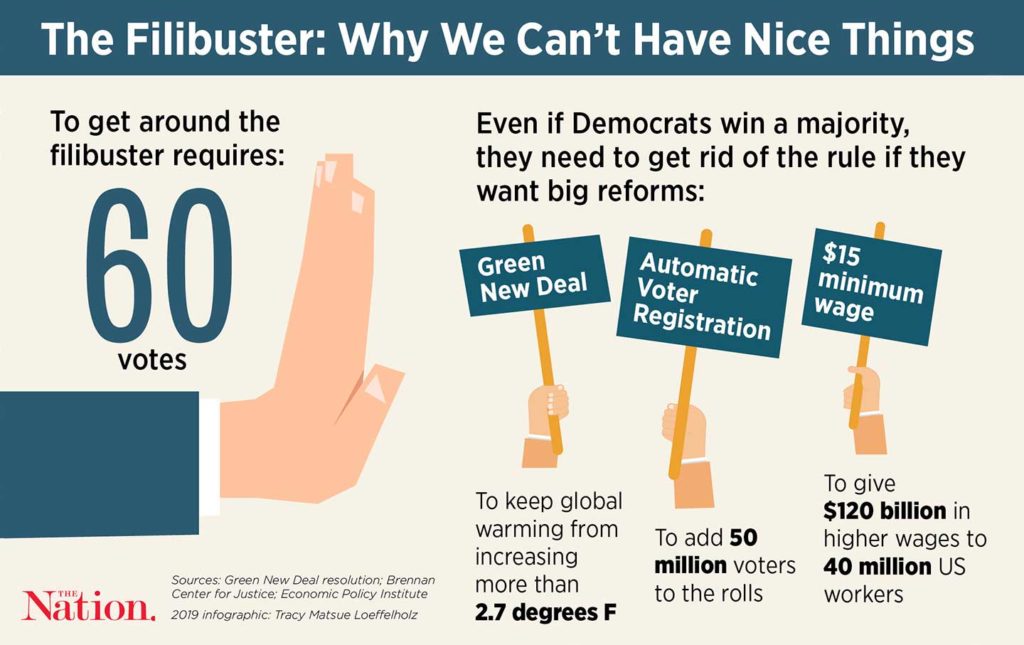

But Lee and Curry present a solid case that getting rid of it is not going to be a panacea. More to the point, many of the big-ticket ideas progressives want, such as illustrated in the article in The Nation from which I borrowed the graphic atop the post, simply aren’t popular enough with Democratic members of Congress to pass into law right now.

There are no panaceas, to be sure, and eliminating the filibuster would not lead to every Democratic fantasy passing into law–especially with a majority of 0 votes plus a tiebreaker.

I think there is value, as noted in the OP, in taking away excuses from legislators. If they won’t get the job done when they can, voters need to know that.

All I really want is a system wherein the actual interests of voters are adequately represented in the national legislature which leads to policy-making oriented towards those interests. To really accomplish that we need massive reform. Eliminating the Filibuster is a step in that direction, but a small and imperfect one at best.

@Steven L. Taylor:

The cynic, while nodding in agreement, thinks, Dr T, isn’t asking for much. Knowing that it means tearing down the existing system and starting from scratch, but acknowledging that we can’t even get rid of the filibuster.

Unfortunately we are more likely to descend into an authoritarian state than reach the point where the system is working for the populous.

All the more reason to kill it. Make them own their votes instead of hiding behind Susan Collins’ skirts.

“For instance, in 2009-10, Senate Democrats never came close to passing a climate-change bill.”

I mean, this strikes me as the canonical example that, yes, the filibuster *is* the problem. They abandoned the bill because 60 was out of reach, but it was reported at the time that they had around 50 votes for some version of the bill. Seems likely that Reid could have struck a deal to get 51 if that had been the standard.

And in the decade since then carbon emissions have continued to accumulate in the atmosphere and air pollution from fossil fuel usage continue to cause hundreds of thousands of premature deaths every year. Every year of delay makes the climate problem more expensive and harder to solve.

I agree with the principle but suspect that at least some voters realize it already and that the many/most of the ones who don’t probably aren’t paying enough attention to vote intelligently and in their own interests anyway. (Go team!)

Were the researchers able to count the number of times bills that died in utero, or were never even considered because, ‘It’ll just get filibustered anyway’?

It’s government.

Nothing is a panacea.

With the filibuster, the Democrats don’t even have to try to agree among themselves.

Kyrsten Sinema would like a word with you. She bothers me more than Manchin, because she isn’t from West Virginia — her political situation is not as dire.

@Sleeping Dog:

As noted in an OP from yesterday, the party establishments are so weak they can’t even get their own houses in order, so something like elimination of the filibuster (which would be completely doable if party discipline was activated) is too much to ask for.

I’m coming to the conclusion that our system isn’t fixable, so tearing down the existing system and starting from scratch looks more and more like the only possible path forward. The question then becomes not how to repair, but how to precipitate the end with as little collateral damage as possible.

@Scott F.:

Show me a revolution that ever worked out well for regular people, and I might join you. As paralyzed as the system is, do you want Americans circa 2021 making fundamental decisions on rights?

@Michael Reynolds:

A year ago, I was pulling for Elizabeth Warren for POTUS, because I thought Trump was so obviously horrible that his presidency would be broadly seen as the political nadir it was and the country would be ready for a bold pull away from the hateful, xenophobic, authoritarian worldview he epitomizes. I was wrong. Trump wasn’t the bottom, he just opened the door that leads down to greater depths.

So, I don’t know that I’m calling for ‘revolution,’ Michael. Trump has demonstrated that tearing down the existing system can happen with the system’s cooperation. I’m just wondering if we could hurry up the race to the bottom, so we might somehow ignite enough backlash that we might be bold enough as a country to accept change. The helpless muddling through has played out.

@Gustopher:

sinema’s approval numbers are in the toilet, the other az senator has pretty good numbers.

Ending the filibuster does make it easier for parties to act like parliamentary parties when they control the House, Senate, and Presidency, which is really what they want to do. So what we’re likely to see is even less than we do now with a divided government since each party will want to wait until it gets the trifecta. At that point, they’ll ram through as much as they can.

Whether that result constitutes an improvement in governance is questionable at best.

Also, as I’ve tried to point out here many times before, and as we saw with judicial nominations, getting rid of the filibuster is more likely to benefit Republicans due to the structure of the Senate and the way the parties are currently geographically sorted. So Democrats, be careful what you wish for.

@Scott F.:

Sounds good in theory, but once that rock starts rolling, you can’t control where it ends up, and very often the result really bad. So for all the flaws of our present system, I would rather keep it as is than tear it down and blindly assume the replacement will be better.

Anyone familiar with the way parliamentary democracies function could have given the same advice. Public policy doesn’t make wild swings every time the government changes, for the reasons James explains. Elections are usually won by small margins, and the members of parliament with slender majorities get very antsy about what Sir Humphrey Appleby* would call ‘courageous decisions’. Even when there’s a landslide, most politicians are educated enough to understand how temporary their triumph is likely to be.

*A character in the greatest political series ever made, the BBC’s Yes Minister/Yes, Prime Minister. A ‘courageous decision’ is one likely to lose the next election.

@Gustopher:

Sinema narrowly won the Special Election for John McCain’s seat.She faces another election for a full 6 year term in 2024. Arizona is like West Virginia in many ways. Additionally Sinema was considered a moderate Democrat when she was in the House. She’s walking a tightrope.

Joe Manchin is the best example of this.

For example, he had basically killed any one that statehood for Washinon D.C. will happen:

https://www.vox.com/2021/5/1/22413869/joe-manchin-washington-dc-statehood-democrat