Too Many Law Schools, Too Many Lawyers

Neither Law Schools nor law students are admitting the fact that the legal market has changed significantly.

Andrew Sullivan points to an article by Anne Lowry at Slate noting a rather astounding disconnect between law school enrollment and the actual demand for new lawyers in the employment world:

The job market for lawyers is terrible, full stop—and that hits young lawyers, without professional track records and in need of training, worst. Though the National Association for Law Placement, an industry nonprofit group, reports that employment for the class of 2009 was 88.3 percent, about a quarter of those jobs were temporary gigs, without the salaries needed by most new lawyers to pay off crushing debts. Another 10 percent were part-time. And thousands of jobs were actually fellowships or grants provided by the new lawyers’ law schools.

The big firms that make up about 28 percent of recent grads’ employment slashed their associate programs in 2009 and 2010, rescinding offers to thousands and deferring the start dates of thousands more. Worse, the profession as a whole shrunk: The number of people employed in legal services hit an all-time high of 1.196 million in June 2007. It currently stands at 1.103 million. That means the number of law jobs has dwindled by about 7.8 percent. In comparison, the total number of jobs has fallen about 5.4 percent over the same period.

At the same time, the law schools—the supply side of the equation—have not stopped growing. Law schools awarded 43,588 J.D.s last year, up 11.5 percent since 2000, though there was technically negative demand for lawyers. And the American Bar Association’s list of approved law schools now numbers 200, an increase of 9 percent in the last decade. Those newer law schools have a much shakier track record of helping new lawyers get work, but they don’t necessarily cost less than their older, more established counterparts.

Even for those 3L’s who do have jobs waiting for them, it’s not necessarily the high-paid position that many think it is, and sometimes barely enough to pay off seven years worth of student loans:

Prospective law students usually look at average pay at graduation. But the average hides substantial inequality: There are the jobs at white-shoe firms that pay about $160,000 per year to precent graduates, and then there are the rest of jobs, which generally pay between $45,000 and $60,000. Almost no salaries are near the median or the average. They are clustered at the bottom, with fewer high earners, many of whom come frLom a handful of super-elite law schools, up at the top. That means that most students do not meet the break-even salary—the starting salary that would make law school tuition a good investment, estimated at around $65,000.

Students simply “cannot earn enough income after graduation to support the debt they incur,” wrote Richard Matasar, the dean of New York Law School, in 2005. “Even those making the highest salaries find that the debt that they have accumulated while in school may tax them for years.”

And yet, year after year, college students continue to flock to law schools in record numbers.

Partly, I think it’s because of the supposed glamor of the legal profession as projected in the entertainment media. Legal dramas of one kind or another, none of which accurately portray what is often the day-to-day drudgery of practicing law, have been a staple on television since the L.A. Law years, and even before then if you go back to the days of Perry Mason. Some people see that and think “Hey, I’d like to be a lawyer too.” For others, I think the decision to go to law school is often made because of a lack of anything better to do at the end of a four year-college career where one has obtained a degree in Political Science that is of little use in the real world unless one wants to become an academic. For these people, go to law school ends up being a substitute for trying to find a way to apply what they’ve already learned toward making a career of some kind. The problem with that is that law school isn’t something one should do on a whim, and the legal profession has little to do with the day-to-day world of Denny Crane or Arnie Becker. Someone who goes to law school based on those factors is bound to be disappointed, especially when the reality of real-world legal practice hits them in the face three years down the line.

Another factor is one that I noticed when I was in law school in the early 1990s. Back then, we were in a relatively modest economic downturn and the job picture for college graduates was worse than it had been in many years. The result was that enrollment at law schools across the country was much higher than it had been in many years as students who might have otherwise cast their lot with the job market decided to ride things out for a few years in the hopes that the economy would improve. The economy did improve over those three years of law school, of course, but not by that much and when the Class of 1993 graduated it faced a tough job market, although not as nearly as tough as the one that graduates have faced over the last two years.

What’s somewhat confusing is the fact that the admittedly bleak legal job market doesn’t seem to be dissuading people from signing up for law school:

The harsh realities of being a young lawyer have not stopped thousands from enrolling in law school during the recession. Veritas Prep, a graduate school admissions consulting firm, found in a recent survey that four in five prospective applicants still plan to apply to law school even if “a significant number of law school graduates were unable to find jobs in their desired fields.” Only 4 percent were dissuaded.

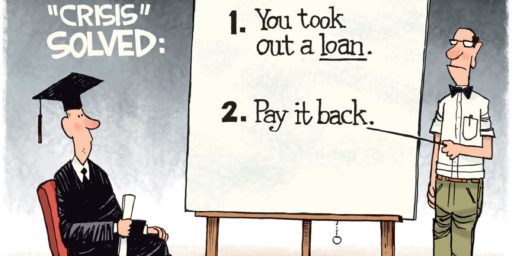

Some would see this and conclude that law students are idealistic and entering the profession because they want to “do good.” Others would say that these students are simply crazy in that they’re not realistically thinking about their own futures and the tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debt they’re about to incur. I say it’s a sign that law schools aren’t being honest with students about the world they are being prepared for. If they were then students wouldn’t be signing up to incur an almost unmanageable load of debt with the risk that they might not end up earning enough money to pay it off in anything approaching a realistic amount of time.

There are many good reasons for becoming a lawyer, but thinking you’re going to end up with a glamorous job making big bucks and handling important cases isn’t one of them. Odds are, you’re either going to spend many, many years in a law library doing research for someone else, or you’re going to be working in the nitty-gritty of a small to medium sized firm where there are no glamorous cases and little reason to think you’ll be driving that BMW by the time you’re 28. If you can live with that, and only if you can live with that, then go to law school.

Or, as they put it in this video:

It’s funny because it’s true.

That’s been the case for decades. The practice of law is divided between the partners and associates working for a handful of big law firms with a heavily Wall Street and corporate clientele, drawn from just 15 schools, and everybody else.

Just minutes before I read this post, I was thinking that we should stop all subsidies to law schools and their students.

The bootleggers-and-Baptists coalition would be a mix of:

(1) people who think our country has too many lawyers already (with an interest in expanding the volume of law & regulation) and/or just want to cut a bit of spending, and

(2) existing lawyers who would prefer not to have all this new blood competing for their work, driving down their wages and cutting throats so that they can eventually see the outside of a corporate basement and the inside of a courtroom.

Go over to Above the Law to get an earful of the bitchy whining going on among law students and recent grads these days. There’s no way in hell that incurring a six-figure student loan debt makes rational sense.

OTOH, if we do start that ‘First, let’s kill the lawyers…’ thing, the job prospects might improve.

IMO the net effect of all of these lawyers is that every clerk working at the DMV will have a law degree. How does that phenomenon factor into the “government workers are higher paid because they have more skills” narrative?

Lawyers should become engineers so they can use all that “intellect” to actually produce something of intrinsic value. Between lawyers and the government they produce, this country has become a consumer nation versus a producer nation. Today’s lawyers are diluting the profession and undermining the ability for individuals to live freely.

Better this surplus of lawyers work at the DMV than out suing everyone for every little thing in hopes of extorting some cash to survive on.

Is there another career where having an excess means the rest of us suffers? To many engineers is likely to lead to some home brew innovation outside the box of the big companies. To many doctors is likely to lead to quality care earlier in the emergency response chain. To many lawyers is likely to lead to harassment over every little slight or robo-foreclosures using fraudulent documents in hopes that volume makes up for quality work.

I think there is definitely an element of the profession being glamorized on tv-where no lawyer on TV is poor and has student loan debt to pay off.

I don’t think taking on too much debt for college and post college work is unique to lawyers, but I do think a lot of people who go to law school expect better returns than some other graduates. I think they are expecting six figure incomes and fancy office space as seen on TV, and are shocked when what they make doesn’t come close much less help pay for the loans.

I think most law students, like most of all Americans, think you can’t really go wrong getting a professional graduate degree. One of the most commonly cited reasons I hear is that legal skills are needed in many types of high-paying jobs, sometimes expressed as, “You can’t wipe your ass without a lawyer nowadays.”

I think it’s worse than that: Law schools aren’t even communicating with prospective students on this issue at the time the applicants are making the crucial go/no go decision. Which is to be expected. A business would almost never try to dissuade part of its target market from buying their service, and law schools are certainly businesses. (Besides, the inquiry into whether its worth it to go to law school would quickly become whether it was worth it to go to this particular law school, which would delve into metrics and information that law school faculty and administrators would potentially find embarrassing to disclose.)

The only way this will improve is if the ABA starts requiring mandatory disclosures to prospective students even before they apply. I have no idea how likely this is to occur.

“The only way this will improve is if the ABA starts requiring mandatory disclosures to prospective students even before they apply. I have no idea how likely this is to occur.”

I suspect law schools know where to find lawyers to fight off any such requirements.

Steve

Dave Schuler: basically correct. You’re unlikely to make the big time unless you went to one of about 15 schools. Some can make it if you came out top of your class or summa from the next tier of schools. I suppose if you went to a mickey mouse school like Regent you have a chance of a job in a Republican administration but that’s about the size of it.

The problem with the U.S. is that in the current economy, the U.S.produce enough high paying jobs for about 5-10% of the whites and Asians to be able to escape blacks and Hispanics. The problem is that 30% of the population are pursuing those jobs.

A longer term question is what will happen to the middle class whites who do not earn enough to escape living in a neighborhood dominated by blacks or Hispanics. Will most of them try to move to places Vermont to get away from the blacks or Hispanics? Will they stop having children to be able to afford a better neighborhood?

I have always found it strange that most politicians refuse to face the changing demographics of the U.S and accompanying policy implications.

Ah, if only I could have a full time job doing legal research and nitty gritty work for the higher-ups. But many of us law school grads can’t find work outside of *document review* – which basically means sitting at a computer all day looking through meaningless documents tagging or categorizing them. And 95% of the time, the lawyer in this situation is working for a big corporation, not the individual client many of us hoped we’d have. Frankly, any college grad could do the work, but it’s work consigned to lawyers for ethics reasons, and it’s the painfully boring reality of big city law school grads who didn’t come in the top 25% of their class.

After all those student loans, I wish someone would give me a new lawyer loan to help me get started in private practice. Or at least I’d like a job doing that legal research and nitty gritty stuff mentioned in the article. I can dream.

The solution is obvious: Lawyer Dome!

Two lawyers enter, one lawyer leaves.

Maybe that’s how bar exams should be conducted.