Yes, College Is Worth It (If You Graduate)

While it's been much derided in recent years, there's a definite economic benefit to obtaining a college degree,

College education has taken something of a hit among pundits in the United States of late. The combination of tuition rates that continue to rise at rates that bear no rational resemblance to either the ability of people outside the upper class, or who don’t qualify for full financial aid, to pay and the impact that the Great Recession had on employment had on new college graduates over the past five years has led many people to put forward the idea that we overstate the value of a college education. Perhaps there’s some merit to that idea in the abstract, but as David Leonhardt notes at The New York Times the numbers still show that people who complete a college education end up better off than those who don’t:

Some newly minted college graduates struggle to find work. Others accept jobs for which they feel overqualified. Student debt, meanwhile, has topped $1 trillion.

It’s enough to create a wave of questions about whether a college education is still worth it.

A new set of income statistics answers those questions quite clearly: Yes, college is worth it, and it’s not even close. For all the struggles that many young college graduates face, a four-year degree has probably never been more valuable.

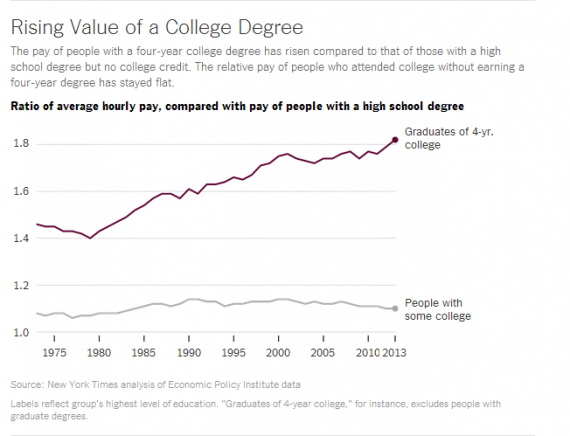

The pay gap between college graduates and everyone else reached a record high last year, according to the new data, which is based on an analysis of Labor Department statistics by the Economic Policy Institute in Washington. Americans with four-year college degrees made 98 percent more an hour on average in 2013 than people without a degree. That’s up from 89 percent five years earlier, 85 percent a decade earlier and 64 percent in the early 1980s.

There is nothing inevitable about this trend. If there were more college graduates than the economy needed, the pay gap would shrink. The gap’s recent growth is especially notable because it has come after a rise in the number of college graduates, partly because many people went back to school during the Great Recession. That the pay gap has nonetheless continued growing means that we’re still not producing enough of them.

“We have too few college graduates,” says David Autor, an M.I.T. economist, who was not involved in the Economic Policy Institute’s analysis. “We also have too few people who are prepared for college.”

(…)

According to apaper by Mr. Autor published Thursday in the journal Science, the true cost of a college degree is about negative $500,000. That’s right: Over the long run, college is cheaper than free. Not going to college will cost you about half a million dollars.

Mr. Autor’s paper — building on work by the economists Christopher Avery and Sarah Turner — arrives at that figure first by calculating the very real cost of tuition and fees. This amount is then subtracted from the lifetime gap between the earnings of college graduates and high school graduates. After adjusting for inflation and the time value of money, the net cost of college is negative $500,000, roughly double what it was three decades ago.

This calculation is necessarily imprecise, because it can’t control for any pre-existing differences between college graduates and nongraduates — differences that would exist regardless of schooling. Yet other research, comparing otherwise similar people who did and did not graduate from college, has also found that education brings a huge return.

In a similar vein, the new Economic Policy Institute numbers show that the benefits of college don’t go just to graduates of elite colleges, who typically go on to to earn graduate degrees. The wage gap between people with only a bachelor’s degree and people without such a degree has also kept rising.

Perhaps the best way to see this is in the accompanying chart:

There are plenty of caveats, of course.

There are plenty of caveats, of course.

Most importantly, of course the findings only hold if you actually get through college and graduate. As the chart above shows, if you only have “some” college education, the likelihood is that you won’t get much of a benefit

Additionally, the pay gaps among college graduates depending on what field they majored in is well-known and not necessarily factored in to the chart above. However, that simply suggests that students need to think more seriously about what they major in and perhaps aim their education toward areas that will actually help set them on a path to a career. Some bachelors degrees are, quite honestly, largely worthless unless one intends to go to graduate school or pursue a career in academia, while others, such as in the fast growing field of health professions, can lead to a well-paying job right out of college. Students ought to be more prudent when choosing a major if they really care about their future earning power.

It’s also the case that many of the jobs that college graduates get after receiving their Bachelor’s Degree are ones that don’t necessarily require a college degree. Indeed, many graduates have reported over the years that the job they ended up with out of college was one that was largely unrelated to their major, or that they were rarely using much of what they learned to do their job. To a large degree, this is is due to the fact that American businesses place an huge premium on a college degree to the point where they block people who lack them from applying for positions where, arguably, a college degree isn’t necessary. One could argue that employers who are doing this are overvaluing college education, but it may also be the case that they are making the judgment that they skills that one learns in college outside of a specific major — working independently with little direct supervision, meeting deadlines, absorbing new and unfamiliar material — are skills that will help in the business world. Whether that is the case or not, though, it’s obvious that employers have made the decision to give added value to college education for some reason and that they wouldn’t do so if there was no value at all.

None of this is to deny that there are problems in higher education, of course. Tuition is rising too fast, administrative budgets at most large universities are bloated, and student loan debt is a burden that is holding graduates back just as they step out into the working world. In the long run, though, it remains the case that someone who graduates from college will, on average, be better off than someone who doesn’t.

No surprise at all.

The national unemployment statistics always bear out the fact that, in our labor market, it is better to have college degree status than to not have it. Unemployment among those with a college degree is always lower that among those with less education.

The real discussion shouldn’t be college/no-college, but more what sort of college someone should go to. For the class of 2013, average student debt at graduation is $29,400. While that’s certainly considerable, with a 20 year student loan that’s affordable for most college graduates.

A lot of the horror stories we hear in the news about people graduation with hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt are people who insisted on going for the platinum-plated high end private school, when they’d have been just as well served at a considerably more affordable public university.

While I think it’s possible that the finding is correct, I wish the analysis disaggregated things a bit more. In particular I think it’s possible that earnings by workers in a relatively small number of sectors or by a relatively small number of workers in a sector, e.g. physicians, associates working for large law firms, etc., may skew the results.

Comparing people with a college degree to those without a college degree can be misleading in a number of respects:

1. Self-selection is the most obvious. It’s hard to look at counterfactuals, of course and people either go to college or don’t go to college. Even so, it’s important to note that the average person that goes to college is not the same person as the average person that doesn’t.

2. When figuring out whether too many or too few people are going to college, we should actually look at the marginal cases. Forget about the people who went to the University of Michigan… what about the people who went to Eastern Michigan University? Are they better off than people with a similar academic portfolio who chose not to go to college? The kids who don’t presently go to college are more likely to go to EMU than U-M.

3. Despite #1 and #2, I still think that college is most likely going to pay off. But from a collective standpoint, it isn’t clear that these aren’t zero sum gains. Going to college puts you ahead in the line, at the expense of not going to college. If they go to college, they may be ahead of you or behind you depending on the particulars, but they have mainly gone further ahead of those who still didn’t go to college. They are individually better off from where they were, but there’s still a line.

@trumwill:

“1. Self-selection is the most obvious. It’s hard to look at counterfactuals, of course and people either go to college or don’t go to college. Even so, it’s important to note that the average person that goes to college is not the same person as the average person that doesn’t.”

I agree. I think having the work habits and discipline to succeed in college translates well once you leave college (and is a major factor in deciding who graduates and who doesn’t).

The problem is not either going or not going to college, but who. For some people that´s make sense, for many people it does not.

One of the problems with the Autor study and it seems to persist in other is that the definition of college is defined as college or college plus:

This strikes me as duplicitious. The study measures the cost of a four year degree, and compares it to the benefit of four or more years of college, including professional degrees like medical doctors, lawyers, etc.

@trumwill: @Moosebreath: Yes, the “self-selection” aspect can’t be overstated. Anecdotally, I met many junior enlisted soldiers when I was in the Army that were damned impressive and rather obviously as smart as me and most of my junior officer peers. Yet almost none of them went on to professional jobs once leaving the Army, despite the GI Bill as a means of paying for college. I think there’s just something about people who, for whatever reason, don’t go on to college right after high school that indicates a lack of some “it” factor that will be there the rest of their lives.

There are glaring exceptions, of course, with our “own” Michael Reynolds among them. But they’re rarer than hens teeth.

@Dave Schuler: I missed your comment, but as you can see that’s my read as well. I don’t see any reason why we should have to speculate about whether doctors, etc. are sufficient to skew the numbers. The value of a four-year degree versus a high school degree should be based upon the value of the additional four years.

I graduated from college in 1968 from a state school. My tuition was less than $600 a year and I graduated with no debt. I was able to pay for it by working in the summer and part time jobs during the school year. Was it worth it? Yes! Does that apply today? Not so much. You make may more money with a degree but if it takes much of that additional income goes to paying off student debt for decades is it still worth it? I’m not so sure!

@Ron Beasley:

The problem is that the jobs open to non-college graduates are shrinking. Any jobs that pays above market clearing wages will be filled with college graduate applicants. Just because a person with a PhD has a job in restaurant management or sales does not mean that they really benefited from their college degree even if they are not using them.

And last, to the idiot MIT professor who argues for more college graduates, what would be the point when the last three car salesmen I have dealt with had college degrees. Does the U.S. need for college graduates working at Starbucks or selling cars?

@superdestroyer: Yet, the fact that college students are frequently working jobs that don’t require college degrees is mentioned in the opening lines of the NY Times article, and amazingly seems to have no impact on the belief system of the NY Times. Comparing this:

with this:

I can only conclude that unemployed high school students are not the intended audience of the New York Times. They don’t count. Their unemployment rate (which is higher than college graduates) is boring.

@James Joyner: I’d almost prefer the system that many countries have–with one or two years of military or other service right after high school. After which, if they desire, they can go to college.

How many of us spent the first two years of college running around trying different majors because we had no idea what we were interested in, learning what it was like to be adult, and discovering how to take care of ourselves without Mom doing everything for us? (Those of us at MIT who were female were resigned to the constant stream of questions coming from the guys around us: “How do I cook this can of corn…?” “How do I operate the washer?” “How do I know if the water is boiling?”)

Perhaps having a gap year or years isn’t all that bad….

As others have pointed out, there’s a significant potential selection bias problem here. I clicked through twice — once to the NYT article and from there to the methodology appendix of the Avery and Turner paper — but I couldn’t tell from that how the authors controlled for “equivalent person, but didn’t finish 4 years of college”. I also didn’t dig into how they computed the Net Present Value of deciding to go get the degree, which also has some potential pitfalls.

I’m afraid my intuition is to ask “how many people are there out there who could have earned a marketable 4-year college degree, but chose not to?” Where “could have” includes had the finances, family support, lack of immediate obligations, etc. I don’t see it being a very common situation.

Also, quoting from the Avery and Turner paper appendix: “We restrict the sample to white full-time and full-year employees, including only those working more than 35 hours per week and at least 40 weeks during the prior year.” So, don’t go generalizing those huge benefits to just anyone just yet.

@Andre Kenji: I’m not sure that in aggregate your point is correct. The number of Bill Gates’ out there who can prosper without a degree is relatively small (and the number whose fathers were managing partners at law firms and could afford to bankroll their son;s businesses is even smaller). The statistic notes that in aggregate, jobs that require college training pay more than jobs that don’t, which has been generally perceivable at true for a long time.

There are definitely people who shouldn’t go to college. Unfortunately, the identifying factor for those people is that they are going to end up being “the poor.”

As Doug noted, the biggest caveat for this type of study is that it studies aggregate effects. Yes, people who graduate with college degrees (in fields where there are labor shortages) do (significantly) better than people who don’t go to college. To find out whether earning a degree works out better in aggregate you have to study a different aggregation. Don’t look at wages, look at laborers. The average worker with a degree will still do better than the average diploma/GED holder, but the difference may not be $500,000/ lifetime and the net cost of the degree will probably not be -$500,000.

To the extent that we use possession of a B.A. to filter the applicant pool, the net effect will be to limit economic mobility (even if the possession of a B.A. is an indicator of better skill sets). Since conservatives currently tend to see the economy as a zero-sum game, keeping the poor “in their place” is a necessary component of “the market economy.”

@DrDaveT: You make an outstanding point about there being a lot more factors than we think of when it comes to self-selection. Not just a matter of high school performance and school, but family situations and circumstances and whatnot.

Intuitively, I think the last bit, about focusing on white people, is a bit off-base, though. If there is any group that I would actually expect a college degree to do the most for, it’s the more marginalized members of our society. I remember reading recently (maybe a link from here) a study that looked at the effects of where a person went to college. What they found was that it didn’t matter all that much… except for minorities and the poor. I would expect the greatest benefit – to whatever extent there is benefit – of going to college at all to fall to such people. Giving them networking opportunities and a broader sense of things outside of their more marginalized communities.

On the other hand, those are likely the people most likely to go to college and never graduate. So even if I am right above, they have a higher risk as well as a higher reward than my (white, middle and upper-middle class) peers did.

@trumwill:

I thought about this, and I decided that it matters what the mechanism is that makes a degree valuable.

If the degree is valuable because of the skills it represents — JD, MD, engineering degree, accounting degree — then it will be more valuable to underrepresented groups as entry into new parts of the economy.

If the degree is valuable as a ticket to be punched for entry into the club, then there are liable to be other similar tickets that the underrepresented groups don’t have.

Which means we’re back to the observation above, that it probably matters a lot what field your degree is in and what school you got it from. I suspect that a bachelor’s degree in English Lit is a lot more valuable to preppy white kids at a private college than it is to urban black kids at a small state school. This ties back somewhat to my point in a different conversation, about the traditional role of trades as the route out of poverty, and how the focus on college degrees has sabotaged that pathway.

@DrDaveT: Your last sentence is right on. I would be interested to know what the distribution of majors by economic and social class. I used to think that kids from marginalized populations were disproportionately likely to major in something genericly non-vocational like English or History. I’ve more recently been reading about the sheer volume of students going into business and wondering if that’s the more generic major these days.

@DrDaveT:

Absent a graduate degree and sometimes even with one, a degree in anthropology or philosophy generally won’t get you so far as accreditation as a plumber or electrician.

@Grewgills:

This is true, but not nearly as true for an inner-city first-generation college grad as it is for a typical old-money Ivy Leaguer.

Or, to put it a different way — any bachelor’s degree at all from Harvard will get you a pretty good job with prospects at the company owned by your dad’s old Harvard buddy. Personal social networks are more valuable than college credentials for many careers.