We’ve Lost Count of the Dead in Syria

Even the United Nations has given up trying to maintain an accurate estimate.

NYT (“How Syria’s Death Toll Is Lost in the Fog of War“):

In seven years, the casualties of Syria’s civil war have grown from the first handful of protesters shot by government forces to hundreds of thousands of dead.

But as the war has dragged on, growing more diffuse and complex, many international monitoring groups have essentially stopped counting.

Even the United Nations, which released regular reports on the death toll during the first years of the war, gave its last estimate in 2016 — when it relied on 2014 data, in part — and said that it was virtually impossible to verify how many had died.

At that time, a United Nations official said 400,000 people had been killed.

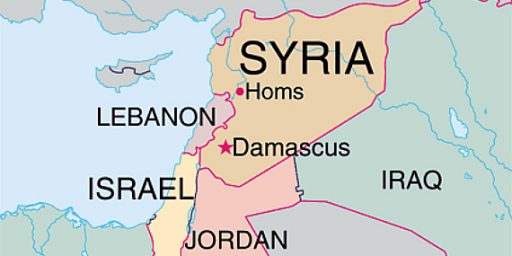

But so many of the biggest moments of the war have happened since then. In the past two years, the government of President Bashar al-Assad, with Russia’s help, laid siege to residential areas of Aleppo, once the country’s second-largest city, and several other areas controlled by opposition groups, leveling entire neighborhoods. Last weekend, dozens of people died in a suspected chemical attack on a Damascus suburb.

American-led forces bombed the Islamic State in large patches of eastern Syria, in strikes believed to have left thousands dead. And dozens of armed groups, including fighters backed by Iran, have continued to clash, creating a humanitarian catastrophe that the world is struggling to measure.

Historically, these numbers matter, experts say, because they can have a direct impact on policy, accountability and a global sense of urgency. The legacy of the Holocaust has become inextricably linked with the figure of six million Jews killed in Europe. The staggering death toll of the Rwandan genocide — one million Tutsis killed in 100 days — is seared into the framework of that nation’s reconciliation process.

Without a clear tally of the deaths, advocates worry that the conflict will simply grind on indefinitely, without a concerted international effort to end it.

[…]

The last comprehensive number widely accepted internationally — 470,000 dead — was issued by the Syrian Center for Policy Research in 2016. The group, which was based in Damascus until that year, was long seen as one of the most reliable local sources because it was not affiliated with the government or aligned with any opposition group.

But now, just getting a death certificate is problematic in Syria, let alone a collective tally of the dead, said Panos Moumtzis, a United Nations assistant secretary general and regional humanitarian coordinator for the Syrian conflict. And civilians make up the largest portion of the death toll.

Since there are 18 different authorities issuing documentation, in addition to the government in Syria, Mr. Moumtzis said, many civilians fear that having a death certificate issued by the “wrong authority” could jeopardize their relatives.

“Even in death, they worry that one day if they go to declare it they will be in trouble for it,” Mr. Moumtzis said, further complicating tracking.

Some monitoring groups are still keeping count from afar, but their numbers vary, are estimates at best, and have not been verified by international groups. These monitors work with networks of contacts in Syria and collect reports on social media and from the news to compile casualty estimates.

The most prominent of these groups, the British-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, said last month that at least 511,000 people had been killed in the war since March 2011. Many organizations rely on this tally as the best current assessment. The group said in March that it had identified more than 350,000 of those killed by name; the remainder were cases in which it knew deaths had occurred but did not know the victims’ name.

There’s a lot to unpack here.

As to the notion that, “Without a clear tally of the deaths, advocates worry that the conflict will simply grind on indefinitely, without a concerted international effort to end it,” that’s been the case virtually since the beginning. We’re now into the eighth year of this conflict and there’s no end in sight. There has been plenty of international effort, but it’s mostly gone into killing one faction or another in this conflict. Russia’s alliance with Assad and veto power in the UN Security Council essentially precludes meaningful international peacekeeping efforts.

For its part, United States has not chosen a side in the conflict. To be sure, former President Barack Obama repeatedly said that “Assad must go,” but never evidenced a strategy to make that happen, much less backed a faction with any hope of replacing him. We’ve bombed the hell out of ISIL but have essentially treated that as its own fight, separate from the larger civil war, despite its implications for the conflict. We’ve backed Kurdish fighters who happen to be on our State Department’s list of terrorist groups and watched our NATO ally Turkey fight them.

That more than a half million people, mostly civilians, are credibly believed to have been killed in this war is awful. That many more are likely to be added to their number is sad, indeed. But it’s not at all obvious what anyone can do about it, aside from taking in refugees fleeing the carnage.

And of course, this President has essentially shut the door to refugees from this horror even as he seems intent on engaging in activity that makes it likely that many more will die. Europe has been better at taking in refugees, but the strains on their domestic institutions, as well as the fact that they have a far different, and far more controversial, history when it comes to being open to outsiders, are becoming obvious even in nations such as Germany and France.

I honestly don’t know what the “the answer” is, and I don’t think anyone really does. It’s easy to say we should do “something,” but nobody seems to know what that something is, and all of the proposed solutions only seem likely to suck us into what has become a never-ending conflict that still has the potential to drag the rest of the region around it into a wider war that could prove catastrophic.

When you have a major, nuclear-armed state involved in the war, there isn’t much that can be done.

We can discourage authoritarian governments, and set an example of free and democratic governance, which runs counter to the trend in the US and much of

Europe as of now.

I know I’ve said this multiple times before, but it seems to me there is something blatantly obvious we can do about it – directly target Assad himself and his senior officials/commanders. As folks have repeatedly noted, dictators like Assad are more than happy to rule the rubble because they know losing the war is an existential threat to them, so attacking their military or infrastructure doesn’t work. So, the obvious (to me) answer is to make defying us an existential threat to them personally as well. I really don’t get why that isn’t immediately clear to everyone.

@R. Dave:

And what happens if we’re successful? Who takes control in Syria?

The most likely answer is nobody, that Syria becomes another lawless state like Yemen and Libya, and another breeding ground for terrorists. The difference is this time it would be happening in a nation that lies right at the center of the most fundamental divide in the entire Middle East. The dangers of a regional war at that point would increase, not decrease.

This is the same choice we faced when we invaded Iraq in 2003, and look at the mess we created there.

Besides, the Russians (and Iranians) have far more invested in keeping Assad and his regime in power than we do in unseating him. They’re not going to give up easily, and there is no upside for us in confronting them in a proxy war like this.

@R. Dave: What @Doug Mataconis said. Presuming the Russians aren’t willing to go to WWIII to protect Assad, we can surely take him out. We’re really good at that. See: Gaddafy, Saddam, etc. But those places are worse off than they were with their horrendous dictators, thanks to the vacuums we created.

To be clear, I’m not talking about strikes aimed at achieving full-scale regime change like we pursued in Libya and Iraq. I’m talking about a limited strike aimed solely at killing Assad himself and maybe a handful of his closest associates. If Assad happened to have a heart attack tomorrow, the regime wouldn’t immediately collapse, and Syria wouldn’t unavoidably devolve into a failed state. There would likely be some jockeying for power at the top, but the broader apparatus of the regime would remain intact, so once that top-level power struggle was resolved, the regime could continue to exercise control over the country as a whole.

The point of that kind of personalized strike would be deterrence, not regime change. Honestly, a near miss would actually be the best outcome. Assad can survive and retain power…as long as he doesn’t cross our red lines (including chemical weapons). If he does cross those red lines, though, the risk he faces is not some marginal increase in damage to his military assets; it’s his own death, which is presumably all he really cares about. Similarly, if Assad happens to get killed in that punitive strike, then whoever succeeds him at the head of the regime is also welcome to retain power without interference from us…so long as they don’t cross those same red lines. And we will have the recent precedent of Assad’s death to give our deterrence credibility and teeth for those successors (and every other dictator we give an ultimatum to in the future).

In short, dictators like Assad clearly seem to make policy decisions based on their personal interests, not their country’s national interest, so we need to personalize the consequences of them crossing our red lines.

I’m convinced that had they known what they were getting themselves into, SC couldn’t have gotten more than one or two states to join them and Lincoln would’ve sworn on a stack of bibles he would never-ever end slavery.

Nevertheless we were lucky it ended so quickly. We can only pray Syria doesn’t have this going on for decades, like it did in Lebanon.

@R. Dave: I am not sure of the principle underlying your recommendation. I understand that killing some guy gets rid off him, but who would we target? Bad guys in general would include some with ties to the USA; we were quite close to people like the Shah and Pinochet whose hands were not unblemished. Going for guys in opposition to US interests would look a little uncivilized to the rest of the world. Somewhere along the line other nations might follow our example; if the Chinese had whacked Bill Clinton for the 1999 missile attack on their embassy in Belgrade, I would not have like that.

the last year of obama’s presidency we took in like 15,000 syrians. Once trump became prez the door slammed shut.

If trump walked out the door tomorrow and got hit in the face by a meteor I’d have to rethink my atheism.

Interesting article in the Atlantic regarding the morale of American troops. James you probably have some insight into this and I believe we would like to hear your thoughts.