When Is A Fish A Document?

The Supreme Court heard argument this week in a case involving a somewhat strange application of Federal law.

Near the end of the Supreme Court’s last term, the Court accepted a case that presented the seemingly bizarre question of whether a fisherman who tossed a fish back into the water had broken documents retention rules contained in the Sarbanes-Oxley law that is primarily meant to regulate the stock market and financial industry. Earlier this week, the Court heard oral argument in the case, and, if anything, the Justices seemed about as confused by the argument in the case as a lay person might be:

WASHINGTON — Most of the justices seemed troubled by Supreme Courtarguments on Wednesday about the prosecution of a Florida fisherman for throwing three undersize red grouper back into the Gulf of Mexico.

The fisherman, John L. Yates, was convicted of violating the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, a federal law aimed primarily at white-collar crime. The law imposes a maximum sentence of 20 years for the destruction of “any record, document or tangible object” in order to obstruct an investigation.

Mr. Yates’s primary argument was that fish are not the sort of tangible objects with which the law was concerned.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. seemed to agree. He asked what people would say “if you stopped them on the street and said, ‘Is a fish a record, document or tangible object?’ ”

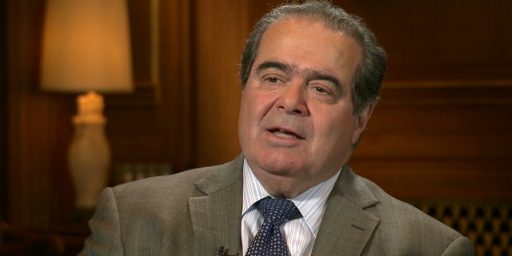

Justice Antonin Scalia said, “I don’t think you’d get a polite answer.”

But Justice Anthony M. Kennedy said it would be odd to let Mr. Yates throw fish overboard, destroying evidence, but to allow him to be prosecuted for tearing up photographs of the fish.

Though Mr. Yates seemed likely to prevail on his main argument, the justice’s real ire was focused elsewhere.

Some were critical of the decision to prosecute Mr. Yates at all.

“What kind of a mad prosecutor would try to send this guy up for 20 years?” Justice Scalia asked. (Mr. Yates was sentenced to 30 days’ imprisonment.)

The Supreme Court has been wary of stretching federal laws to fit minor crimes, ruling in June in Bond v. United States, for instance, that a chemical weapons treaty could not be used as the basis for a prosecution of a domestic dispute.

“Who do you have out there that exercises prosecutorial discretion?” Justice Scalia asked the government’s lawyer, Roman Martinez. “Is this the same guy that brought the prosecution in Bond last term?”

Mr. Martinez said Mr. Yates’s crime was a serious one, involving lying and a cover-up.

Chief Justice Roberts was skeptical. “You make him sound like a mob boss,” he said.

The case arose from a 2007 search of the Miss Katie, Mr. Yates’s fishing vessel. A Florida field officer, John Jones, boarded the ship at sea and noticed fish that seemed less than 20 inches long, which was under the minimum legal size of red grouper at the time.

Mr. Jones, an officer with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and a federal deputy, measured the fish and placed the 72 he deemed too small in a crate. He issued a citation and instructed Mr. Yates to take the crate to port for seizure.

But Mr. Yates threw the fish overboard and had his crew replace them with larger ones. A second inspection in port found only 69 undersize fish and aroused suspicions, and a crew member eventually told law enforcement officials what had happened.

Some justices were wary of the sweep of the law, which applies to “any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of the United States.”

Justice Stephen G. Breyer said the law would allow prosecution for the destruction of a census form. “The risk of arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement is a real one,” he said.

John L. Badalamenti, a lawyer for Mr. Yates, said that sustaining the law would mean that “the American people will be walking on eggshells.”

Mr. Martinez acknowledged that the law may be subject to attack as too broad and vague. But he said those issues were not squarely raised in the case argued Wednesday, Yates v. United States, No. 13-7451.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., who is generally sympathetic to arguments from prosecutors, was skeptical.

“You are really asking the court to swallow something that is pretty hard to swallow,” he said. The law, he said, “is capable of being applied to really trivial matters, and yet each of those would carry a potential penalty of 20 years.”

Lyle Denniston summarizes the argument, and provides some more detail for Justice Scalia’s comment that it made no sense to use this law to prosecute a guy over fish:

From the outset, then, this case had the potential to come down to the question of whether there was too big a gap between the original intent of Congress and the choice that federal prosecutors made in this specific case when they went after the fisherman and the dumping of seventy-two red grouper — itself not a crime but, at most, a civil offense justifying a fine.

That was the theme that an assistant federal public defender from Tampa, John L. Badalamenti, leaned on throughout his time at the lectern Wednesday. The Justices were quite penetrating in their questioning, and, at one point, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, while saying that the lawyer’s objection had “considerable force,” suggested that the reading of the law he was pushing could mean that the law had an even wider breadth than the government had argued.

The exchanges left the initial impression that most of the members of the Court were skeptical of Badalamenti’s points, as they tried various hypotheticals to test just what kinds of evidence his view of the law would allow prosecutors to challenge as an obstruction of a federal investigation. The fisherman’s lawyer wanted the law confined to the destruction of records or other items used to store information, and the Justices spun out a series of scenarios to gauge what that would entail.

Early on, it seemed as if the fisherman’s lawyer was not really getting across his basic argument that the law was drafted in such sweeping terms that it was potentially draconian. Gradually, though, that idea was creeping into the argument, as when Justice Stephen G. Breyer commented that, “at first blush,” the law “seems far broader than any witness-tampering law, any obstruction statute, any lying to a federal agent law that I’ve ever seen.”

(…)

Scalia was saving his involvement for the government’s lawyer, an assistant to the U.S. Solicitor General, Roman Martinez, who came prepared to argue that the law did, indeed, reach the intentional destruction of “all types of physical evidence.”

Within minutes, Scalia leaned forward and, accusingly, told Martinez that he was defending the law and its use for someone who got only thirty days. “What kind of sensible prosecutor does that? Who do you have who exercises prosecutorial discretion? Is it the same guy who brought Bond, last Term?” — a reference to a decision in which the Court had ruled that the Justice Department had gone too far in using a law against the spread of chemical weapons to prosecute a woman for trying to poison her husband’s lover.

Scalia pressed on, noting the potential for a twenty-year prison sentence under this law, and asking “what kind of mad prosecutor” would use that law in a case like this one? Martinez weakly responded that the prosecutors had not asked for a twenty-year sentence against the fisherman.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg then interjected, asking whether the Justice Department provided any guidance, “any kind of manual” to limit prosecutors. Martinez answered that the manual for U.S. attorneys told them that, in choosing what crimes to charge, to go for the “most severe available.”

In view of that, Scalia retorted, the Court was going to have to be “much more careful” about how it interpreted federal criminal laws. When Martinez tried to portray the fisherman as someone who ordered the destruction of evidence, disobeyed a federal officer, and worked out a cover-up scheme, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., commented: “You make him sound like a mob boss.”

Just what sentence did prosecutors recommend here, Justice Kennedy asked. Martinez said twenty-one to twenty-seven months, but then added that thirty days here was “reasonable” and twenty years “would have been too much.”

The hearing’s tone had changed totally, and Martinez was on the defensive throughout the remainder of his time. He tried to recover by going over the specific words and headings in the law, trying to show what Congress had intended for the law.

Denniston’s colleague Amy Howe summarized that part of the argument for her “In Plain English” recap of the argument:

Assistant to the Solicitor General Roman Martinez encountered even more skepticism during his thirty minutes of oral argument, as Justice after Justice voiced concerns about the potentially sweeping reach of the government’s interpretation of the statute. Justice Antonin Scalia was Martinez’s main antagonist, unleashing a barrage of questions and comments that removed any doubt about where his sympathies lay. He complained that, under the statute, Yates had faced a maximum sentence of up to twenty years. What federal prosecutors, he asked Martinez, have this kind of discretion in choosing what charges to bring? Referring to last Term’s Bond v. United States, in which a Pennsylvania woman had been charged with violating the federal laws implementing an international chemical weapons treaty after she tried unsuccessfully to poison her husband’s lover, Justice Scalia asked Martinez whether the prosecutor in this (Florida) case was “the same guy” as in Bond. “What kind of mad prosecutor,” Scalia continued, “would ask for twenty years” in prison for destroying fish?

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg joined the fray, asking whether the Department of Justice gives federal prosecutors any guidance on what charges they should bring in a case like this. A similar statute, carrying only a five-year maximum sentence, would also apply to Yates’s case, she noted. Martinez’s response – that a manual instructs federal prosecutors to bring the charges that are most severe – drew even more ire from Justice Scalia. He warned ominously that, “if that’s going to be the Department of Justice’s position, we’re going to have to be very careful about interpreting the scope” of laws like these.

The Chief Justice also appeared skeptical of the government’s argument. He inquired whether the government would bring charges under this particular statute whenever someone destroys a “tangible object.” Martinez assured him that the federal government does not actually file criminal charges in “every fish disposal case.” However, that answer appeared to provide little comfort to the Chief Justice, who shot back that the important thing was that, on its reading, the government could do so. And the possibility of a twenty-year sentence, the Chief Justice suggested, would give government lawyers “extraordinary leverage” to try to get someone to plead guilty. Justice Stephen Breyer would later echo these concerns, telling Martinez that, “if you can’t draw a line, there is a risk of arbitrary or discriminatory enforcement” of the statute.

What happened here is often the fun part of oral argument at any level. With little warning you can see an argument head off in a direction that nobody was anticipating, and it can often end up being the basis for what happens in a given case. In this case, led by Justice Scalia there appears to be some segment of the Court that is wondering why this case even made its way before them and how a prosecutor could make a seemingly bizarre decision like using a law meant to deal with destruction of documents in the course of a securities fraud investigation to prosecute in a case dealing with the proper size and number of fish taken from a waterway. Given the potential sentence in this case, which admittedly is probably not the sentence that Yates would receive in this case given Federal sentencing guidelines, that question seems to be even more important and the overkill that the prosecutors are engaging in becomes even more obvious. Let’s accept for the sake of argument, then, that what Yates did was wrong both in that he was catching fish outside the appropriate regulations and that he attempted to dispose of the evidence before he got back to port. Potentially, there would be some charge that could be brought against him for destruction of evidence, although that leaves open the question of whether throwing a fish that is still alive back in the water is really “destruction” of anything but lets leave that one aside for the moment. Given that, it’s unclear to me why it was necessary to charge Yates under the law with the most extreme law possible, except to chalk it up to the rather unpleasant habit of prosecutors at all levels to overcharge and over punish.

As noted above, there seem to be some similarities between the way the Justices reacted to the government’s argument in this case and their decision last term on a case dealing with the use of a chemical weapons treaty to prosecute a woman who had attempted to poison a woman who was having an affair with her husband. In that case, the Court ruled that the treaty could not be used in a domestic law enforcement matter because the case was too far afield from the intent behind the law that as adopted to enforce the treaty. That seems to be the case here as well. Even accepting the legitimacy of Sarbnes-Oxley, the law was obviously not intended to cover fish even if its wording could be stretched to do so. Given that, it would seem likely that the Court’s best option here would be to throw out the conviction on that basis. Yates may have done something wrong, but what he did wrong was not what Congress was intending to punish when it adopted this law and prosecutors should not be permitted to stretch the law in this manner.

Here’s the text of the Oral Argument:

Which part of this is the funniest? It’s hard to tell. I was amused that by dumping the crate and replacing its contents, the crew managed to get all the way from 72 undersized fish to 69 undersized fish. FAIL.

It’s not the crime it’s the cover-up!

I guess if it isn’t the question about Obamacare subsidies, then legislative intent might matter. If it is a question about Obamacare subsidies, then only a hypertechnical reading of the law matters, and nothing else. Do I have that right?

Ok, I’m not sure why everyone is focusing on “document” instead of “tangible objects”. You can touch a fish, therefore it is a tangible object. It seems pretty clear he attempted to get rid of physical evidence in order to not get in trouble. That’s illegal as stated, regardless of its physical form. So yes, technically the criteria has been met. That being said….

The prosecutor needs to go to remedial law school (and possibly a counseling session). There are other laws applicable so why this one was chosen, I have no bloody idea. I wouldn’t be arguing about whether the fish applies; I’d be arguing that this law has no earthly business being applied to me. Mr. Yates appears to be going for the reductio ad absurdum route for this case, emphasizing not the incorrect application of a strange law to his violation, but rather the tangible objects that demonstrate his violation. A neat trick – “Don’t look at what I just did – look at what it IS!”

Why in the hell did they take this case in the first place?

Me, walking down the street, chewing gum, throwing wrapper at trash can, missing.

Cop: “Sir, that’s littering”

Me: “Sorry” picking up wrapper and depositing in trash can.

Cop: “Got’cha, that’s 20 years for disposing of evidence!”

Odd case; I hope for a blistering attack on the prosecutor in the final decision.

What situation does an officer of the law charge someone with a violation and then return the evidence to them to self-report? I’m guessing that the fishing violation was entirely civil, otherwise there would be self-incrimination issues. Bridging a civil issue to a felony is a huge leap.

Also, the evidence wasn’t entirely destroyed. The officer could testify to the number of fish.

If anything, the fishermen lost the chance to claim three of the fish were not undersized.

@Mu: That’s genius.

Clearly, the federal government was on a fishing expedition ……..

Just a red herring that they floated for the halibut. I cod just get a haddock thinking about it.

I can’t properly render an informed opinion as this deserves until I see the arguments re-enacted by puppies.

On a slightly more serious note… two thoughts. First, don’t we already have laws about falsifying/destroying evidence that could have been used? Second, could this law be used against the IRS over all those conveniently-lost documents in regards to the Tea Party targeting?

Beating the guy about the head and shoulders with Sarbanes-Oxley seems over the top for a minor civil violation. Wouldn’t spoliation sanctions and an adverse inference be sufficient?

I suspect they’ll have a hard time getting a fair herring on this evidence.

Rodney, your comment is a red herring.

@rodney dill: Whale, now you’re just floundering for jokes. And this is no fluke; you always do this. Why don’t you just take a minnow or two before posting them? Every now and then, just stay on your perch in the peanut gallery. You don’t always have to make a bass of yourself.

How is a fisherman supposed to know how big a particular fish is before they get it into the boat?

@Jenos Idanian #13: I don’t know whether to click Like or Dislike in response to your Hurricane of Puns.

But looking more closely at this case, I think the key issue is that gov’t inspectors, when telling the fishermen to preserve evidence, forgot to say, “Salmon says … “

The other day the “Supreme” Court was dealing with Jerusalem. Now a case involving a fisherman and his fish. See the significance here ?

@JWH: nothing to carp about.

Recent comments on this thread have smelt.

@Jenos Idanian #13:

Not just that. The CIA destroyed the torture tapes. Millions of e-mails went missing under President Bush. Evidence was destroyed in the Jewel v. NSA case. Daryl Issa claims that Obama Admin officials have destroyed evidence on at least twenty occasions and Democrats claim the Bush Administration had a similar or worse track record. Related to this specific case, Sarbanes-Oxley does not apply to federal agencies, even though it applies to everyone else.

Law are for plebs, not rulers.

Conceding that it’s absurd, unjust, and abusive of prosecutorial discretion that someone go to prison for 20 years for this offense, I don’t understand the legal rationale for Yates. Mr. Mataconis says that “the law was obviously not intended to cover fish even if its wording could be stretched to do so,” but that’s not at all clear to me.

As the Scotusblog recap makes clear, the statute was explicitly intended to deal with issues outside of financial matters, and the plain text of the statute criminalizes the destruction of a “tangible object.” In fact, Yates doesn’t seem to even be contesting that this; his argument is around the definition of “tangible object,” which he would like to mean “tangible object that is not a fish.”

I sympathize, but it’s not what the law says, and presumably Congress gets to punish even minor crimes absurdly and / or harshly. (In the previous chemical weapons case, on the other hand, it was tough to argue that the prosecution wasn’t using “chemical weapon” in a way that was at odds with the typical meaning, which is why they lost and deserved to.)

So I am genuinely confused as to how the Supreme Court is going to manage to justify overturning a law on the basis that they think the sentence is too harsh… while simultaneously paying lip service to the notion that they don’t make laws, only interpret them. Can someone help enlighten me?

@Jenos Idanian #13: Don’t get crabby about it.

@GeoffBr:

Statutory interpretation:

“Tangible object”, in this case, must be interpretted as limited to the same class as “record” and “document”.

@Stormy Dragon:

I can understand the argument, but it was rejected twice before by other courts, so while plausible it’s hardly “obvious.” (The government also has a plausible case that the statute was designed to be read broadly.)

More importantly, a read of the transcript shows that the justices are basically concerned with the potential injustice of the sentencing and the abuse of discretion. I find it interesting that they seem to be arguing from the consequent.

That said, I’d be happy to see Yates win.

@GeoffBr:

That’s not an argument, that’s the canon of statutory interpretation. If the government wanted it to be interpretted broadly, it should have been written “all tangible objects, including documents or records” rather than “documents, records, or tangible objects”.

I’m going to get serious once again and cite this as one of my pet peeves, and it’s one that seems to be far more prevalent from the left. Whenever something bad happens, there’s a push to make a new law to address the latest bad thing. It seems that no one stops to ask “isn’t this already covered by existing laws?” We already have laws against tampering with evidence and the like; there was no reason to take a law intended to address crimes of high finance on a fisherman.

My favorite example: remember the murder of James Byrd in Texas by white supremacists? There was a huge push to pass a hate crimes law in the wake of his brutal death. Then-Governor Bush vetoed it, saying that there were already sufficient laws on the books to deal with things like this. Three men were charged in his murder. One of them testified against the other two. Two were sentenced to death; the cooperative one is serving 40 to life, with his first parole opportunity in 2038, when he’ll be 63. I think that’s a just outcome, and I don’t see how a “hate crime law” would have led to a better outcome.

And as to the “they still had 69 too-small fish,” I wonder if they threw overboard the smallest ones and replaced them with fish closer to the limit, to make it seem less bad. They knew they’d been busted, but if they tossed out the real small fry (sorry) and put in ones that were ALMOST legal-sized, it might not look so bad for them.

@Stormy Dragon:

They are supposed to throw it back immediately if it is undersized. Unfortunately, depending on how they were caught, many will still die, but most will survive to grow to legal size and hopefully reproduce before they are caught again. This fisherman apparently kept them with the intent to sell or eat them himself rather than following the law. He then tried to destroy the evidence of what he did in perhaps the most idiotic and inept way possible. I don’t know that the law used was entirely proper, but he was an idiot and an asshole and is a part of the reason that our fish stocks are declining as they are. Too many commercial fishermen still seem incapable of thinking in the long term and will given the chance fish smaller and smaller until the stock collapses to make sure that they get their profit early. That trend to failure when allowed to continue unchecked is the tragedy of the commons.