Where Are America’s Jobs?

What happened to the 15 million jobs that were supposed to be created in the past 10 years but weren't?

National Journal editor-in-chief Ron Fournier says his colleague Jim Tankersley asks, “The single most important story of the 2012 presidential campaign.”

It’s a big one: “What happened to the 15 million jobs that were supposed to be created in the past 10 years but weren’t?” It’s a fascinating question and a well written and researched piece. Alas, the answer is rather unsatisfying: Damned if anyone knows.

The years between the brief 2001 recession and the 2008 financial collapse gave us solid growth in our gross national product, soaring corporate profits, and a low unemployment rate—but job creation lagged stubbornly behind, more so than in any economic expansion since World War II.

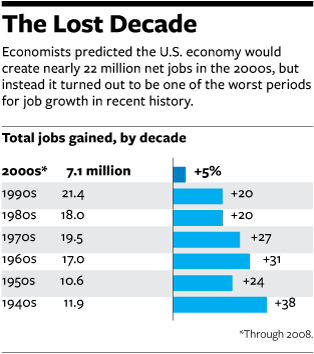

The Great Recession wiped out what amounts to every U.S. job created in the 21st century. But even if the recession had never happened, if the economy had simply treaded water, the United States would have entered 2010 with 15 million fewer jobs than economists say it should have.

[…]

We know what should have transpired over the past 10 years: the completion of a circle of losses and gains from globalization. Emerging technology helped firms send jobs abroad or replace workers with machines; it should have also spawned domestic investment in innovative industries, companies, and jobs. That investment never happened—not nearly enough of it, in any case.

If we can’t figure out why, we may be doomed to a future that feels like a long jobless recovery, no matter how fast our economy grows. “It’s the trillion-dollar question,” says David E. Altig, senior vice president and research director for the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, where economists are beginning to explore the shifts that have clubbed American workers like a blackjack. “Something big has happened. I really don’t think we have a complete story yet.”

We certainly didn’t see it coming. At the turn of the millennium, the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicted that the U.S. economy would create nearly 22 million net jobs in the 2000s, only slightly fewer than the boom 1990s yielded. The economists predicted “good opportunities for jobs” and “an optimistic vision for the U.S. economy” through 2010.

Businesses would reap the gains of new trading markets, the projection said, and continue to invest in technologies to boost the productivity of their operations. High-tech jobs would abound, both for systems analysts with four years of college and for computer-support analysts with associate’s degrees. The manufacturing sector would stop a decades-long jobs slide, and technology would lead the turnaround. Hundreds of thousands of newly hired factory workers would make cutting-edge electrical and communications products, including semiconductors, satellites, cable-television equipment, and “cellular phones, modems, and facsimile and answering machines.”

[…]

A few researchers caught early warning signs of the trend. In 2003, economists Erica L. Groshen and Simon Potter at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York warned in a paper that “structural changes” in the economy appeared to be hindering job creation. Groshen and Potter noted that after the past two recessions, in 1990-91 and 2001, economic growth had picked up long before jobs began to reappear, bucking a long historical trend of growth and jobs returning in tandem. The explanation, Groshen and Potter said, was a shift away from the time-honored American tradition of laying off workers in bad times and recalling them when the clouds parted.

“Most of the jobs added during the recovery have been new positions in different firms and industries, not rehires,” they wrote. “In our view, this shift to new jobs largely explains why the payroll numbers have been so slow to rise: Creating jobs takes longer than recalling workers to their old positions and is riskier” when recovery still appears fragile.

In other words, American companies had adopted a more cold-blooded attitude toward recessions, one that fit the new model of globalization and automation. Technology made it easier to lay off your 100 least-effective workers and ship their jobs to India, or to replace them with a software program that made your remaining workforce dramatically more productive.

Guesses abound: Americans aren’t sufficiently educated or properly trained for the jobs that are being created. Companies are hoarding cash, for whatever reason, rather than investing in equipment and people. Profits are going to shareholders rather than being reinvested. Mostly, though, it appears that Americans just don’t make anything anymore.

A recent paper by researchers at the Asian Development Bank Institute concluded that the iPhone, one of the United States’ top innovations of the past decade, actually contributes nearly $2 billion to our trade deficit because it is almost entirely produced and assembled in Asia. The paper also raises a conundrum for lawmakers and business leaders alike: If Apple moved its assembly line to the United States and created domestic jobs but didn’t raise the cost of the iPhone, the company would still turn a 50 percent profit on every one it sold.

Maybe Apple’s greed is at fault. Maybe the government is to blame for not making the industrial climate more hospitable to Apple and other job producers. The harsh reality is that workers, companies, and lawmakers all need to readjust if we ever hope to rev up the job-creation machine again.

Regardless, there’s no consensus on the cause, much less what, if anything, we should do about it. But it’s not good. The iPhone case is scary, in that we just skip the few years where something is “high tech” and therefore manufactured by American workers. Which means the money is in inventing and marketing such things, not building them. That’s not a recipe for a robust middle class.

“Mostly, though, it appears that Americans just don’t make anything anymore.”

Or if they do, they don’t for long:

This company opened in 2008, got $43 million is aid from the state of Massachusetts , then two years later, bailed. The cynic in me says the company intended all along to bail, and used the tax breaks and funding to get itself set up for the move.

GOVERNMENT MOTORS, according to the Detroit Free Press, ” is investing $540 million to build fuel-efficient engines at its plant in central Mexico. Labor Secretary Javier Lozano says the plant in Toluca will produce lower-emission 1.6- and 1.8-liter, four-cylinder engines for export. The investment will provide 500 new jobs.”

$540 million for 500 new MEXICAN JOBS. LOOKS LIKE OBAMA IS OUTSOURCING NOW!

Although I guess that’s one way to get illegals to return to their homeland.

Ooops. Left out the link: Solar Panel Maker Moves Work to China

“Americans aren’t sufficiently educated or properly trained for the jobs that are being created”

Its true – I am stunned that every time I need a new data architect or etl developer or j2ee developer all I get are applicants from china or india. I want to hire american for these good paying jobs but nobody is applying for the positions….it scares me that we have become so under skilled.

“If Apple moved its assembly line to the United States and created domestic jobs but didn’t raise the cost of the iPhone, the company would still turn a 50 percent profit on every one it sold.”

Proof that Apple customers are suckers?

I think the general mistake was believing the economists’ claim that those 15m jobs should have been created. That was just their guess, about the future. And no one, not even economists, can predict the future.

Now, in terms of what’s going on now with jobs … you could probably do a calculation of how much “embedded labor, in hours” shows up at our ports as imports. Plot it for the last 50 years, and see the story. We used to import raw materials. Now we import iPhones.

@jp: My initial Twitter response to Fournier was, “Maybe the story is just that economists can’t predict the future for s#&t?”

Which is, of course, true. But they were assuming the first decade of the millennium would follow longstanding patterns. It didn’t.

Like most disasters, there is more than one cause. Offshoring is part of the problem. The investing class stopped investing in vehicles that create jobs. Our best and brightest went into law and finance. Our level of innovation dropped (research is overly concentrated in bio-sciences).

Steve

BTW, to further call BS on economists’ predictions, look at the employment-population graph for the last 50 years: link

Why after running in a band from 1948 to 1975 did it suddenly break upward? It was social change plus economic change. Women went to work, because they had to. Inflation hit and more money had to be earned and spent.

Now we have fallen almost all the way back to the 1948 to 1975 band. Why? Hard times … but I don’t think anyone knows how this will work out in the future.

I’m not sure we should expect a return to peak employment, or even that it would be a good thing. I mean, send retirees back to be WalMart greeters, and you’ve raised that employment ratio … but it’s not all roses.

(I was typing as you did james. I guess my cite above is that they weren’t really looking at truly longstanding patterns, but rather at a 30 year trend. well, definition of “longstanding” I guess.)

It’s getting to the point where I’d rather spend more money for the ” made in USA” logo and get a quality product. So much of the stuff coming out of China is not only badly made but in some cases dangerous to your health.

The odors of these products never seem to go away. I don’t know if its the formaldehyde or heavy-metals. But the Chinese have found a new way to eliminate Americans …tainted products. I’m disgusted with their “stuff.”

Maybe it’s time for our government to let foreign-earned profits back in this country … as long as the money STAYS HERE.

Maggie Mama, I hate to break it to you but it’s going to be darned hard to avoid Chinese products. If you eat anything that’s colored, flavor enhanced, texture enhanced, or vitamin enriched, it contains Chinese products. Practically all food additives are made in China.

If you use anything electronic (I presume you do since you commented here using a computer or a smartphone or something of the like), it was most likely assembled in China from components made all over the place, including in China.

Not much of a way out.

Fact is, it is expensive to have employees in America. Putting aside the take home pay, the actual compensation (salary, benefits, contributions) is about double that. Add in the regulatory compliance costs and the very unstable employee lawsuit environment and you’ve encouraged any effort possible to reduce those costs. Namely, find ways to not have American workers. Either through automation or through moving jobs that are not high return off shore. Add in all the other regulatory compliance costs and who produces in the US when labor, energy, etc. are cheaper elsewhere. That then gives you a product that you can price competitively.

I’m not saying that we abolish regulations or that we get rid of employment law, but it does seem we’ve reached a point where the protections are now preventing job creation. If that were to indeed turn out to be the case, it is time to discuss where the balance should be. We can’t as a nation act as the unions and prefer no job over a job with less pay. That’s the idiot route.

The Oil Drum just had a post discussing all the “jobs” created in wind energy. And how they are touted as so much better than that nasty efficient coal energy production since wind needed more workers. However, more employees means more expensive and in this world, the only person who pays is the consumer, either through higher prices or higher taxes for subsidies.

Globalization means a leveling of the workforce, with the result that manufacturing is going to move to where the labor is cheapest, and fly from where it’s most expensive (U.S.). Union busting was encouraged with that in mind. It’s neoliberalism at work, endorsed by both parties, and the results are pretty predictable. How is it that anyone is surprised by this?

The other thing going on is the increasing cost of energy. Cheap energy has dramatically increased our standard of living by allowing us to employ all sorts of mechanical and chemical slaves, with the result that production is greatly increased. American oil production peaked in the early 70’s, and we’ve had to spend more and more of our money overseas to get oil, which itself is becoming more expensive due to global scarcity.

I would also mention policies (bi-partisan as much as I can see) that favor large corporations at the expense of competition and small business. How many jobs have been lost to mergers and acquisitions? How many jobs have been lost because existing regulations make it impossible for a new businesses to compete in a specific field?

I’m in favor of government regulation (for the most part) but large corporations have managed to politically set themselves up with a sweet deal in this country at the expense of everyone and everything else because they can afford to buy politcal capitol (directly or indirectly.) I would dearly love to see our markets opened up to encourage new start ups and reduce the size of the largest corporations. That might even cause some of the largest competitors to spend some of that hoarded money on things such as customer service, innovation and community outreach.

I would also toss an update of the patent and copy right laws so that if an owner does not use some intellectual property that it is released to someone else that will, but that is another topic entirely.

I don’t think that it needs to be that way, Nick. I think we’re letting the Chinese make it that way.

It’s really not quite that simple. The productivity of American workers is a lot higher. It’s not just that the Chinese make 4% of what Americans do.

Dave:

Nothing is ever that simple, and books can and are written on the details of change in any economic system.

However, The aim of globalization is to open markets, including labor markets, to increase economic efficiency. The movement of capital to cheap labor is an intended result of globalization and it is definitely a cause of lost manufacturing employment in the U.S.

Textile factories can operate just as efficiently with low wage labor as they can here in the U.S. In fact, there really isn’t much that we can that can’t be done just as well overseas. Farming, but even there we are killing our topsoil with pesticides and are dependent on petrochemical fertilizers to maintain production goals.

Worse, Americans are increasingly average to poor when it comes to being educated. We still have elite universities, but increasingly many of the top students come from overseas.

Also, John McCain was right–there are jobs Americans won’t do. We’ve become soft and pampered. That happens to any materialistic people. And we are grossly materialistic.

Also, the rising cost of energy is a huge factor in this. We are working to buy energy to keep working to buy increasingly expensive (more man hours per kilocalorie) energy. As a result, we are draining capital that is being used in other countries to build their infrastructure and manufacturing base.

Finally, our infrastructure is being starved of investment because of this cycle.

Kevin Philips did a nice job of discussing the decline of energy and the rise of the FIRE sector of the economy in “American Theocracy.”

Nick is absolutely right about energy. Trillions have been lost over the last few years to foreign countries importing oil to us. Until we get the price down there will be no jobs and no recovery.