Whose Deaths Should We Honor?

The line between "hero" and "victim" is blurry and rendered meaningless when the former is over-used

My latest for War on the Rocks, co-authorized with Pauline Shanks Kaurin, is out. It will look familiar to regular readers, as I workshopped an early draft here.

It’s titled “Whose Deaths Deserve to be Honored?” It’s long and complicated but here’s the setup:

The confluence this year of Memorial Day and commemorations of the 100,000 Americans who had died from COVID-19 should naturally have sparked a conversation about whose sacrifices should be honored by the nation. Since it did not, let’s start it here.

At first blush, the two issues could not be more different. Soldiers who die serving their country in war are heroes to be lionized. Those who die from disease are victims to be mourned. But a closer examination shows that it’s not that simple. There are many ways to serve the community and varying levels of risk entailed. Ranking them is no easy task.

The line between “hero” and “victim” is blurry and rendered meaningless when the former is over-used. While many display courage when called upon to do so, few are truly heroic. That’s true of those who serve in uniform and those who perform essential but less-heralded jobs that benefit society.

The conclusion:

Those who continue doing hard and necessary jobs during perilous times deserve our respect. While they were just doing their jobs as they always have, they were thrust into taking risks that the rest of us could avoid. But most of them aren’t heroes; they’re just ordinary citizens carrying on with their roles in the community. Similarly, most who serve in the armed forces, even during wartime, do so honorably and deserve the thanks of a grateful nation. But few are heroes; most never have the opportunity to be.

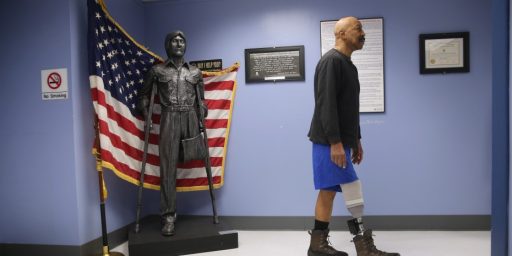

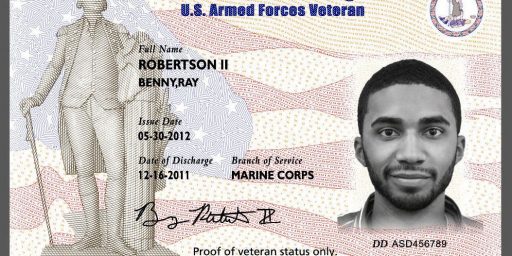

At the same time, if ordinary citizens have an obligation to carry on their work for the good of the community, society owes them as well. In the case of our soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines, we owe those who die in our service to take care of their families; and to those wounded, whether physically or psychologically, to take care of their medical needs. Abraham Lincoln’s charge, adopted by the Veterans Administration as its motto, “To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan” needs updating to reflect the service of women. But we should honor the sentiment better than we do. Moreover, Americans should demand their leaders be more cautious in sending them off to die in wars they can’t win and where the safety of the nation is not at stake.

For those in other occupations, while thanking them for their service beats ignoring their sacrifices altogether, perhaps the best way we can honor them is to mitigate their risk. Society can ensure nurses and doctors have the proper protective equipment and a well-funded national pandemic response system in place ahead of the crisis rather than forcing them to risk their lives because they didn’t. And society should require businesses to implement procedures to make it less likely that those who stock our shelves and pack our meat catch preventable diseases because their bosses cared too little about their safety.

There’s a lot in between at the link.

There’s really nothing stopping us from having a national Day of the Dead where we honor all who have been lost, even if they don’t “deserve” it. Simply by being American – no, simply by being *human*, we should have national day off to recognize all of have died. Everyone can claim it for their cause – X amount of people died of Y, remember them on Fri!! Everyone gets a chance to honor their dead because even the most evil, unrepentant criminals have family or someone who cares they’re dead.

I feel we force a false dichotomy when we “honor”. Either you deserve all the praise or none. Why can’t we have a day when everyone gets their due and then we can use Memorial Day for it’s intended purpose. I’m not particularly jingoistic but we should have day for those who went out and lost their lives fighting for this country. If we need more days to recognize those who’ve lost their lives in other worthy causes, then by all means set up more days. God knows Americans need more time off as we work ourselves to the bone. It’s an cheap, easy win for Trump too if he’s smart – proclaim a new national holiday wherein all those lives lost in the last year are celebrated and let special interests debate over who’s day it really is. Meh, I’ll send the suggestion to Biden’s campaign.

Honor isn’t finite – there’s enough for all so long as we respect them. We can afford to give it COVID victims, victims that died of racism, medical personnel who’ve died tried to stop a pandemic and so on. Pretending we must choose cheapens everyone’s respect.

Relevant: Memorial Day was begun by African-Americans who wanted to commemorate those who those who had died during the Civil War to bring about their freedom. It later was expanded to include the dead of all wars.

@Monala: There were tons of Decoration Day activities that followed the Civil War; one of them was put on by freedmen. They didn’t invent the holiday but they’re certainly part of it.

I don’t see it as whether a particular group of dead are more “deserving.” We just have different days to honor/remember (whichever word you prefer) different groups of dead.

On Memorial Day, we honor U.S. servicemembers killed in war.

On Holocaust Remembrance Day, we honor those murdered in the Holocaust.

On AIDS Remembrance Day, we honor victims of AIDS.

On 9/11, we honor the victims of the 9/11 attacks.

There are others.

Eventually, we will have a COVID-19 Remembrance Day, and that will be entirely appropriate.

We don’t need a national “day of the dead.” Anyone who wishes to do so can observe the Latinx Day of the Dead in October. A lot of people already do. As the country becomes more brown, this holiday will become more common, and I’m all for that.

We should honor lives and achievements; it reminds us of them. Everyone dies, it’s hardly exclusive.

Also: please bring back the down-thumb; it’s silly just to have one.

The civic as opposed to the personal purpose of honoring the dead is to instruct future generations. It says, ‘this is what we expect of the best of you.’ Once upon a time people thought it’d be great if we all grew up to be Robert E. Lee. Now most people would prefer that you grow up to be John Lewis.

It will never be a rational process because the values of the past don’t always endure. Change comes. Perspectives shift. We have very little need right now to inspire people to serve in the military, that’s become a profession, and we aren’t likely to need, or even want, millions of volunteers.

We need a different word than, ‘hero.’ I propose borrowing from Yiddish: Mensch.

If you serve your country, state, city or family well and faithfully, you’re a mensch.

“exemplar”?

@Nightcrawler:

I’m not sure how much honoring of war dead we do on Memorial Day but it dwarfs all the others. I would have to Google to tell you when the AIDS and Holocaust days are but they’re not holidays nor widely celebrated in the US. And I’d be shocked if there were a COVID day; we don’t have one for the 1918 flu.