Against the Electoral College III: Policy Implications

How does the Electoral College influence policy and campaigning?

The third in an ongoing series.

The third in an ongoing series.

Ok, so we’ve looked at abstract theoretical reasons for arguing against the EC and have also explored some historical issues. How about a more practical set of examples? How does the EC influence policy and campaigning?

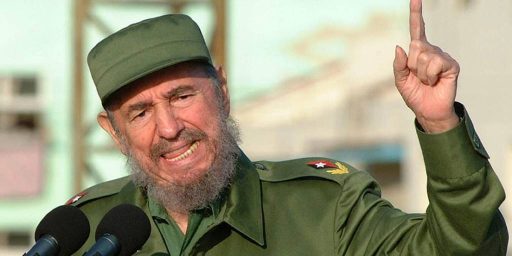

A simple illustration of the problem with the Electoral College is our policy towards Cuba. Specifically, one might ask why it is so difficult for candidates and presidents to directly tackle what has become an absurd foreign policy vis-à-vis Cuba? While it is impossible to reduce any complex policy problem to a single cause, there can be no doubt that a major contributor to our Cuba policy has been the electoral college.

That’s nuts, you say? Consider that Florida has a large number of electoral votes and that it has been a swing state for some years now (indeed, throughout the entire post Cold War period). As such, not only does every vote count in Florida in terms of awarding its electoral votes, it has been a linchpin in the overall process to elect the president in the electoral college (especially in the 2000s).

What candidate in that environment is going to risk alienating the Cuban ex-patriot population by talking rapprochement with Cuba? What sitting president is going to do so if he seeks re-election for himself or for a co-partisan to succeed him? It is not worth the political risk. There can be no doubt that the politics of Florida, coupled with the politics of the electoral college, combine to have long-term effects on US foreign policy (see Eckstein 2009 for a run-down of policies on Cuba that correlate quite well to election years).

Indeed, here are some more examples of this type of behavior from a 2004 USAT piece:

In recent weeks, the president has made a series of decisions boosting him in states that could be critical to his re-election. Last month, he announced that the federal government would buy back $235 million in offshore oil and gas drilling leases in Florida. He signed a 10-year, $190 billion farm bill popular in Iowa, Missouri and elsewhere in the Farm Belt. And he imposed tariffs of up to 30% on imported steel, an important issue in West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

[…]

“One week he’s the president of Pennsylvania, and the next week he’s the president of Iowa,” says Steve Moore, president of the conservative Club for Growth, which criticizes Bush for approving protectionist measures.

And before some raises the objection: yes, candidates and presidents will seek to pander to specific constituencies no matter what. However, do we really want a system that incentivizes such pandering only to swing states at the expense of large swaths of the country already considered sufficiently red/blue? As Strömberg concludes in his paper on the subject: “the Electoral College system provides sharper incentives to target a few states with favorable policies” (37).

If one looks at Table 3 from Strömberg’s article, one finds, for example, that in the 2000 electoral cycle, 24 states received no campaign visits from either the presidential or vice presidential candidates of either party (including large population states like Texas, New York and Massachusetts).* In 2004 that number was 20 states. Meanwhile, Florida received a total of 25.5 visits in 2000 and 52 in 2004. Another swing state, Ohio, saw 15 visits in 2000 and 41 2004 when it was especially seen to be in play. Why would we want a system that encourages such campaign tactics?

In short: part of the reason for wanting to do away with the EC is to encourage candidates who will have to wage truly national campaigns, not campaigns that can take a slew of states for granted and only focus on a handful. What is interesting is that a lot of people (in the comments of previous editions of this series, in fact) will often argue is that they fear that a true national vote will lead to too much geographic concentration in campaigning without recognizing that that is exactly what we currently have under the system they are defending.

*”The visits data was collected by Daron Shaw and is described in Shaw (2007). I have excluded the early September visits, since I use polling information from mid September. Visits by vice presidential candidates are counted as 0.5 presidential candidate visits. For example, in 2000, Bush visited Florida seven times while Cheney visited six times. Consequently, the weighted number of Republican visits to Florida in 2000 is ten. The visits data was collected by Daron Shaw and is described in Shaw (2007). I have excluded the early September visits, since I use polling information from mid September. Visits by vice presidential candidates are counted as 0.5 presidential candidate visits. For example, in 2000, Bush visited Florida seven times while Cheney visited six times. Consequently, the weighted number of Republican visits to Florida in 2000 is ten” Strömberg (14).

Works Cited

Eckstein, Susan. 2009. “The Personal Is Political: The Cuban Ethnic Electoral Policy Cycle.” Latin American Politics and Society. 51, 1 (Spring): 119-148.

Shaw, Daron R., 2007. The Race to 270. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Strömberg, David. 2008. “How the Electoral College Influences Campaigns and Policy: The Probability of Being Florida.” Working manuscript of work published in American Economic Review. [PDF]