American Exceptionalism in Choosing the Head of State

We are truly exceptional in how we choose the president.

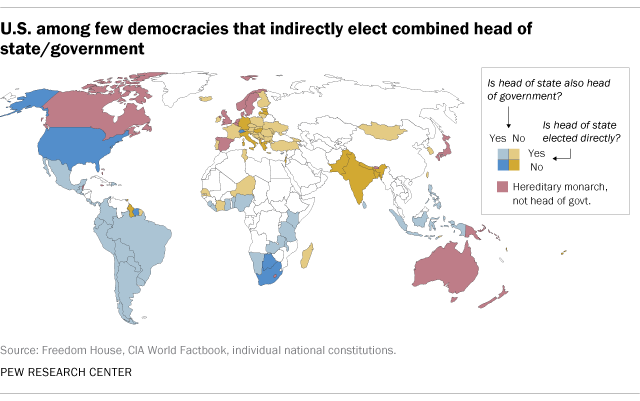

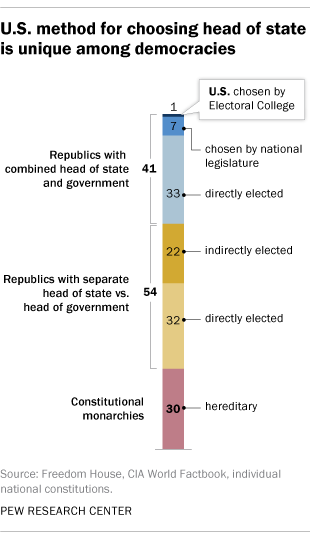

From the Pew Research Center’s FactTank comes something we knew, but with cool graphics: Among democracies, U.S. stands out in how it chooses its head of state.

And:

Note that in this context “republic” means that the head of state is not a monarch (which is true of other contexts as well, but people can get a bit weird about that word).

Note in republics with an elected, separate head of state, they often have only ceremonial powers (which is especially true in the cases with indirect election).

In regards to the other seven cases with indirectly elected heads of state who are also heads of government, they are as follows:

Besides the U.S, the only other democracies that indirectly elect a leader who combines the roles of head of state and head of government (as the U.S. president does) are Botswana, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, South Africa and Suriname. (The Swiss collective presidency also is elected indirectly, by that country’s parliament.)

Basically in all cases, save the US, the indirectly selected head of both state and government is chosen in a way that gives legislative majorities the say (which should, in turn, reflect majority preference in their countries).

Of course, the populations of the Federated States of Micronesia (~105k), the Marshall Islands (~53k), and Nauru (~13k) are all too small to be useful for this kind of comparison. Even Suriname, which has a population of less than 600k, is a pretty different kind of state.

Botswana, South Africa, and Switzerland are all parliament-selected presidents. South Africa’s can be removed by a vote of no-confidence, so it really is more like a Prime Minister. I am unsure as to whether this is true of Botswana’s president.

Switzerland has a unique collective executive (the Federal Council), the head of which (for a one-year term) is the President.

The closest example to the United States was Argentina, which used an Electoral College under its 1853 constitution. While it was used for a number of elections, really the only two that could be classified as fully democratic were in 1983 and 1989. That system was replaced via constitutional reform in 1994.

The system was similar to the US in that there was some disproportional distribution of electors to the provinces (Argentina is a federal system): each province gets two senators and then get representatives based on population. A difference is that the number of electors was allocated by doubling the number of senates plus reps per province. This meant that the advantage for smaller provinces was diminished to a degree. Another major difference was that the provincial electoral vote was awarded proportionally (no unit rule, so if candidate X won 52% of the province-level vote, that candidate would get only 52% of the EV, rather than 100% of them, as is the case in the US).

On another comparative note, Rice Political Scientist Mark Jones noted, in a broader study of the issue of elected presidents noted that out of over 100 cases of elected presidents, most use processes that require an absolute majority:

Today, there are fewer than a dozen presidential electoral democracies

Source: Mark P. Jones. 2018. “Presidential and Legislative Elections.” The Oxford Handbooks of Electoral Systems.

that continue to employ the plurality formula to elect their president, with the most prominent examples being Mexico, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan.

And while uniqueness can mean something is superior, it is hard to make that argument here. None of these systems, as varied as they are, is like the US Electoral College. Importantly, none of them, even though they are indirect in their process, allow the minority to choose the president over the objection of the majority.

I think that last point needs underscoring: it is not just that a plurality can elect our president, or that we could have a minority government (such as happens in parliamentary systems at times), but we have a system wherein the minority of voters can select the president at the same time the same process tells us what a clear plurality of voters want.

Isn’t the biggest issue the fact that the EC (mostly) is “winner take all” rather than proportional?

If the electors voted based on their representative district, wouldn’t a lot of the irregularities be minimized?

I’d be willing to bet a majority of the US population, not necessarily a majority of voters, could not explain even basically how the Electoral College works. Fewer still would be able to say how it was intended to work.

Which makes one wonder why you stick with such an arcane system.

Partly is that it works well for one party, which keeps reform at bay. the other part is most people simply don’t care, or don’t know enough to care, IMO.

@Mu Yixiao: It is a major part of it.

I have another post on what 2016 would have looked like if EVs were proportionally allocated by state that is not quite finished.

@Kathy: Yup, yup, and yup.

Both the EC and the way we apportion Senators needs to be reformed if the Republic is to survive.

I’m inclined to put the blame on the primary system, as opposed to the EC. It’s the primaries that suck so much money, time, media attention into the maw that by the time we actually get to vote, no one has the energy to be citizens.

@Not the IT Dept.: I find the EC more indefensible from an institutional design POV than I do the nomination process (which is fraught with its own problems).

Truth be told, you have to treat the whole thing as one whole (and bizarre) contraption for electing the president.

The president of France is to all intents and purposes a directly elected head of state and government.

Whilst there is a prime minister who is technically head of government and accountable to parliament, the parliamentary elections take place within a month of the presidential elections, and in all of these since 2002 (when the presidential term was changed to 5 years to line up with the parliamentary term) the president’s party has won a majority. The president then selects their own PM and can carry out their own legislative agenda – they can and do replace PMs who decide to start blocking aspects of their agenda. They chair the cabinet, too.

@Archway: In the chart above France is one of 32 republics with a directly elected head of state, but not head of government (as you note).

It is true that the relative power of the president vis-a-vis the PM is linked to what party controls the national assembly, but the pres is head of state and the PM is head of government.

Excellent diagnosis, doctor. So, what’s the treatment? Oh, there is no treatment? Swell.

@Michael Reynolds: The treatment is education + time (and likely more troubling real political events), which will lead to either reform through established channels or via serious crisis.

I was thinking about this kind of potential response earlier today. On the one hand, you aren’t wrong: change is hard (very, very hard). But I reject the notion that I (and others) are just shouting into the void by pointing out the problem and showing a way forward, even if getting people to follow is hard.

As I have noted in some other comments, there is more conversation now about various kinds of reforms now than there was 5 years ago. These things take time (lots of time).

But, sadly yes: no short term answers.

@Michael Reynolds: Although, I will confess to near despair about it all at times (and wonder why I have spent so much time with this stuff…).

Happy, happy, joy, joy, dontcha know.

I think substantive systemic reform–in any domain–requires catastrophe.

The effects of the Great Depression led to quite a few reforms because of how widespread the hardships endured by people became–25% unempolyment is outrageous. Even with the millions of people who had their lives turned upside-down, it took serious political maneuvering, some of which were, uh, shall we say, a little shady.

In contrast, the Great Recession didn’t cause that high a percentage of unemployment. As a percentage of the population, fewer people were left distitute. And we got few substantive reforms from it.

That’s not to say that 2008 wasn’t a catastrophe. It was for many people. Worse, its effects, like the Great Depression, were felt more acutely by people who were not directly involved with the causes of the crisis. But there were enough people able to navigate it that the political will to force real changes to the financial system didn’t materialize. There will be lasting effects to Millenials in the long term, but politics is primarily a short-term game.

Healthcare is in a similar situation. There are enough people happy with their healthcare, that resistance to systemic change ends uo being quite high–the metrics that show the system is expensive and inefficient, like infant mortality, fail to reach salience to people with good insurance.

Systemic political change? Not until there is a serious crisis of legitimacy. Until then, the people who get screwed by the whole system will keep fighting each other.

@Kurtz: This is a reasonable position to take.

@Steven L. Taylor:

I’ve got nothing in principle against shouting into the void. Most of my comments here are exactly that.

We need a die-off of Silent Generation and Baby Boomers. But as we’re waiting for that to happen we’re seeing the Overton Window move rapidly toward acceptance of out-in-the-open corruption and fascism. The youth today may not be the same people in 20 years. They may not be looking for progress, just pay-offs for whatever fraction of the electorate they claim membership in.

@Michael Reynolds:

Technically, euthanasia is a treatment.

Listen to @Kurtz. there are many other examples in history: the black death, the civil wars of Sulla and Marius, WWII, and others.

But I’m a bit, a very little bit, more optimistic. There are attempts, now and then, to change things for the benefit of the masses. Not many, and they don’t always work. Like the Gracchi brothers in Rome. But sometimes they do work, like labor legislation and protection, and the rise of unions, following the industrial revolution.

What those at the top should be made to understand, is that giving up a little now will most likely keep them from having to give up a lot more or give it all up, later.

@Michael Reynolds: The void is pretty noisy these days.

@Michael Reynolds:

So engage a little bit more. My fustration with you w/r/t Sanders isn’t that you disagree. Disagreement and debate are fundamental to democracy.

It is that you are absolutist in a situation that presents no such basis for that response. That’s it.

It reminds me of a Super Bowl pre-game show–The 49ers will win, because their running game is good and their defense is fast. The next guy argues that no matter how good a defense is, bottling up Mahomes for 4 quarters has proven to be exceedingly difficult. The conclusion of one view was correct, and the other incorrect.

But neither reasoning is correct, because the events that occur within the game are largely unpredictable. Take away the OPI called on Kittle, and the outcome may have changed. The ref calls Williams down prior to the ball crossing the plane, setting up a fourth down for the Chiefs inside the one yard line.

On the surface, the Chiefs guy was correct, but even in retrospect, his reasoning cannot truly be verified. Not only that, the first guy can easily say that had Shannahan run the ball on the second to last drive, he may very well have called the game correctly.*

To bring it back to politics, specifically 2016: anyone can say, “if only Clinton had _____;” or “if Comey had not sent the letter;” or “if Obama had more aggressively dealth with Russian interference.”

It’s like a medical examiner establishing the cause of death for an 85 year-old with diabetes, clogged arteries, and a history of multiple strokes. One may be able to rule out foul play, but a definitive cause of death is unlikely. Moreover, if there is significant evidence of foul play outside of the autopsy, the ME’s report may still provide no corroborating evidence given the state of the corpse.

We can provide an autopsy report for the Falcons, the 49ers, and Clinton. But the outcomes cannot definitively be traced to anything in particular that they did or did not do.

The point: events that only get run once are poor candidates to form the basis for induction. And even when we have tons of data from previous contests, like we do in football and in elections, it’s impossible to tell what reasoning would have predicted the outcome–the variables are impossible to untangle from each other.

Each closely contested election is like a football game, the terms that decide the outcome are different in ways that are unknown and likely to remain that way forever. Predicting it, even when the outcome obliges, is a delusion that persists for the people who called it right. The Chiefs guy will gloat that he knew it–there’s video proof! But it ain’t proof of shit.

If Sanders is the nominee and he loses, you will claim to have been correct all along. But you would be nothing of the sort. Worse, that attitude could foreclose future opportunities for good candidates.

It’s best to avoid definitive statements, especially in reference to poorly-defined concepts like electability.

*Even highly paid, talented people at the top of their profession have trouble untangling the relative impact of decisions. Shannahan made a decision in the last Super Bowl similar to the one he made when he was the play-caller for the Falcons.

I mean, there are only two ways to fix it. Either we water the tree of liberty with blood, or we literally persuade an overwhelming majority of the population of 300 million people that it’s a significant enough problem to push for what amounts to a constitutional convention.

The first one is infinitely more likely, and it’s monstrous enough to even conceive of that I prefer to describe it with referential metaphor.

I’ll bet this is one of the reasons why Warren has sunk in the polls…those at the top zealously hold on to what they have as they continue to accumulate more and more…who’s going to stop them from doing that? Does anyone really believe that they can be made to understand? Perhaps there is something to be said for lamp posts…

@An Interested Party:

I’m reminded of King Louis XVI. Sure, he totally effed up the Estates General, and he failed to be decisive at crucial times, but he wasn’t, really, a cruel or unkind man. Had he gone along with the revolution, in its earliest stages, chances are he’d have reigned with ever-diminishing power for many years, or at least he’d have been able to retire peacefully.

Instead, he ended up meeting Madame la Guillotine.

I’m shaky ground here, but the Gilded Age ended and was replaced by more general prosperity, which then led to today, the New Gilded Age.

Which leaves three options I can see:

1) things can change

2) things can change and then change back

3) things can change temporarily while those on top regain their previous predominance.

There is an argument that the Gilded Age led to the Great Depression…so this New Gilded Age leads to a New Great Depression? Oh well, the Great Depression was so bad for so many people that this country actually good positive progressive changes as a result of it…perhaps we do need Great Depression II…