Some Electoral College Thoughts

It really is rife with problems.

James Joyner’s post on consternation over potential third party runs at the White House in 2024 got me thinking about the Electoral College and how it influences third party development and general political behavior in the United States. Plus, I think some key points are worth emphasizing or, in some cases, raising yet again.

Here we go.

What are the Alternatives?

Setting aside the obvious difficulties of change, what are other ways we could elect the president? Presidents around the world are elected via the popular vote, with the two main options being via a plurality (i.e., simply majority or the candidate with the most votes wins even if they do not get 50%+1) or via an absolute majority (requiring 50%+1 of the vote) which is usually accomplished via a run-off but could also be done via instant run-off. There are some variations and tweaks that are possible within these systems (such as allowing a plurality winner if one of the candidates hits a certain percentage, say 40%, but having a run-off if no candidate hits that mark).

We could also tweak the Electoral College. A current proposal, the National Popular Vote Compact, would require states to award their electoral votes in accordance with the national popular vote outcome. Without getting into how this would happen, and what the odds of it happening are, I will simply note that it is possible to retain the structure of the EC but to have the popular vote be the guiding determinant of the allocation of the electoral vote.

Other tweaks include changing the allocation of electoral votes by using the district method, as is the case in Maine and Nebraska. That, however, would be a terrible idea because it would mean that EC would be subject to gerrymandering and all of the electoral pathologies associated with the election of Congress that I often write about. This system is often described in the press as “proportional” but it isn’t.

We could, theoretically allocate the electoral vote per state in a truly proportional fashion, which would be an improvement over the current situation, but would still have several distortions associated with the size of some districts (i.e., the states) and the existing distortion created by each state having two electors automatically regardless of population size. The fact that the House is far too small a chamber given our population growth since the early Twentieth Century is also a problem.

Understanding What the EC Really is

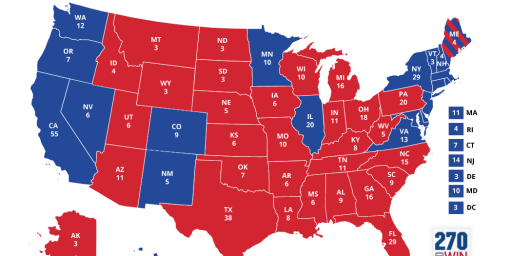

I often complain about the usage of single-seat districts and plurality winners in the US electoral system. But the only thing worse, from a democratic point of view, is the usage of multi-seat districts with plurality winners, which is what we have in the Electoral College. While we in the United States tend to think of the Electoral College as some unique process to elect the executive (and it is) it really should be properly understood as a very peculiar system to elect a collective body like a legislature. This may be immediately obvious to some readers, but it is certainly not the way most voters conceive of it. But consider, the elections of the EC are really 51 individual multi-seat plurality elections plus five single-seat plurality elections. Note that Maine and Nebraska send two electors statewide per state (multi-seat districts) and then have district-level elections for the rest (two in Maine and three in Nebraska). So, there are really 56 total elections that determine who gets the electors.

As such, the state of Texas, for example, is one district with a magnitude (as we say in electoral studies) of 40 (based on its 38 House seats, and its two Senate seats). All of the seats (electors) elected in Texas are allocated on the basis of who wins the plurality of votes in Texas. This also means that each of the 56 elections are winner-take-all, and in 51 of those elections the winner takes multiple electors as a unit).

The Core Problem

For voters to matter, their votes have to be of some mathematical significance to the candidates. This is a major component of democratic accountability. The more that candidates, and by extension elected officials, can ignore certain voters, the worse the quality of democracy.

Indeed, the above sentence encapsulates the core criticism I have of American democracy, as it applies across the board. Only some voters matter. Worse, as I repeatedly note, the ones that tend to matter the most are in the primaries, not the general (this is especially true for congressional elections).

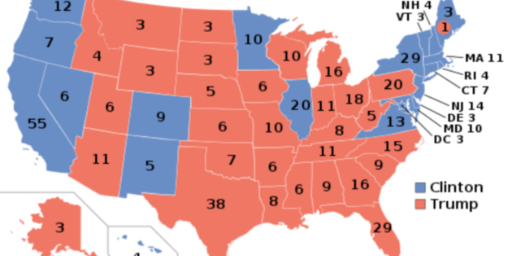

The structure of the Electoral College, contrary to popular mythologizing, does not force candidates to pay attention to small states, nor does it require them to pay attention to a mixture of different kinds of states. Rather, it causes them only to care about competitive states (except when it comes to fundaraising), the number of which are small relative to the whole.

While Republicans will complain that the if we engaged in a national popular vote for president that their voters would be ignored and that the system would be dominated (as the lament often goes) by “New York and California” or, more ominously, “Los Angeles, New York City, and Chicago” the reality is that all a national popular vote would do is require candidates to see all voters as worth their attention–including a lot of Republican voters who are currently utterly ignored.

While the bogeymen of urban blue states may haunt the dreams of some Republicans, allow me to note that Texas and Florida are large population red states. But, more importantly, there are millions of Republican voters in blue states. Indeed, one of the pernicious effects of the EC is to lock us all into a mentality that a state is red or blue without thinking about the voters inside those shapes who are not all one thing or the other.

In 2020, Trump won 6,006,429 votes in California. That is the most votes he won in any state, even Texas where we won 5,890,347. His CA total is only slightly higher than than what he won in deep red AL, TN, and NC combined (6,052,420).

Third Party Thoughts

While it is true that the EC’s plurality-winning processes make it less attractive for third parties to form and compete, I would still argue, as I have repeatedly, that the primary system is more responsible for the lack of third parties. The entry cost is lower, and the potential reward is radically higher, to try and enter the presidential election process via the primaries. And the porousness of the parties further incentivizes that behavior (which was a core point of my recent post about RFK, Jr.).

I think it is also true that, unlike the dynamics in two-round presidential elections, there is no space in the US system for alliances to form between third parties and the two major parties, which further diminishes the incentives for third party formation.

In other words: there is no room to really win much of anything (not states, not electors, not influence, and certainly not the presidency) as a third party candidate. And if what you really want is attention and air time, best to run in one of the two major party primaries.

Primaries have only existed for a fraction of our history (they’ve only dominated presidential contests for the past 50 years), yet the country has been strict two-party for basically the entire time.

@Kylopod: As I have noted before, primaries have been key at the sub-presidential level for more than a century and the fundamental force that forms a party system tends to be the process that elects the legislature.

But, sure, there are other factors at play. And, in fairness, I said: “that the primary system is more responsible for the lack of third parties [than is the EC].” Please at least note that I am not making a monocausal assertion.

I agree that the long-term history of stable bipartism in the US needs to be addressed by my argument. I will note, as I demonstrated here, while the tendency in the 19th century was to two large parties, the absolute number of seat-winning parties used to be consistently higher.

There is a very legitimate analytical question that pertains to a paper I presented last March and that I need to revise, as to what timeframe my hypothesis should apply to.

In many ways, looking at all Congressional elections back to the beginning is a problem because they really are not comparable. Just the issue of suffrage is key: property conditions, gender, race, etc. There is the question of when the ballot shifted from private to public production (late 19th century). Arguably we aren’t even fully democratic until 1965.

And yes, there are a variety of structural factors that inhibit party formation. So while primaries are not the only cause, I am quite convinced they are a main (dare I say primary) cause.

I am open to an argument as to why my logic about incentives as they currently are configured is wrong.

We also don’t see third parties showing up at a state level — either for the federal or state offices.

This surprises me especially with places like California where there is a non-partisan primary. The Republicans are pretty much shut out of everything in state government there, so an Infuriating Manchinesque Pro Status Quo candidate should have an opening, drawing from conservative Democrats and Republicans, and just throw the brakes on the Democrats.

Could even call themselves a Democrat if they wanted.

IMO, this is the primary factor in the mismatch between the popular vote and EC in recent years. The size of the House hasn’t changed for more than a century, despite the US population increasing by almost 240 million people since the Apportionment Act was passed. We’ve also added two states.

We could solve most of the problems with the EC by significantly increasing the size of the House, which doesn’t require a Constitutional amendment.

That wouldn’t get me to my desired end-state – a functional multi-party system, but I think it would make the present system more functional and give time for a reform movement to grow.

I currently live in Iowa.

There is nothing wrong with that. The problem arises that national pundits immediately place way too much importance on Iowa and New Hampshire. The voters in those states are stating their preference amongst the field as it exists then. These are the first votes in a long slog towards nomination. They are those folks preference then. Nothing more.

We don’t winnow the field, y’all winnow the field by how you over-react to our initial take on the list of candidates. Don’t listen to those fools! Don’t listen to us. It’s not our fault.

All y’all over-react, and that’s on you not us.

Buttigieg won the 2020 Iowa caucauses. Clearly. Sanders second, Warren third, Biden fourth.

In my precinct it was Buttigieg, Warren, Sanders, Biden in defending order.

Y’all criticize us for getting it wrong and criticize us for narrowing the field and not voting for the eventual nominee. Boo fricketedy hoo! Narrowing the field is entirely on you. You do that. We voted from our hearts.

I actively enjoy the fact that Iowans often get the eventual nominee wrong. New Hampshire, too. The pre-election consensus choice doesn’t always win. It wobbles wildly. Jeb Bush crashed hard.

If we believed the pundits in the run up to an election Jeb Bush would have been 45. He turned out to be a footnote.

Don’t believe the hype.

We are not telling you folks how to vote. We’re just first. It’s our initial take on the field.

And it is entirely not our fault when the national commenteriot over-react wildly the next morning. That’s on you, not us. That is not our fault and entirely on you all.

It’s one result from one state, the first state. And a caucus state. You all are seriously over-reacting.

@de stijl: If you don’t think that your vote is more important, why do you demand to be first? Obviously directed at Iowa not just de stijl.

@de stijl: with regards to the primaries, apologies if this is a stupid question, but why not have them all on the same day? A truly national Super Tuesday.

Iowans have to make their choice earlier in the campaign, and as we’ve seen before, various additional information surfaces about candidates, scandals break, etc., during the campaign which later primary voters can factor into their decisions but which early primary voters can’t. Similarly, Iowans and early primary states get to cast a vote for any of the crowd of candidates who jump in. Based on those results, some candidates will choose to drop out and later voting states don’t get to express their views on those candidates at all.

I get that the press would hate this, and America would be denied a fun months long politics-as-sport horserace, but it might make more sense?

@Chris:

I think the journey makes the candidate.

If you failed to break the top 3 in Iowa or New Hampshire you can try again in South Carolina and Nevada. Winners don’t quit after the first round.

I think super Tuesday as it currently exists is a dumb idea and the super super Tuesday idea you propose is worse. I want to see a candidate up and down. I want see them high off victory and deflated by defeat. Settling on a candidate too early is foolish in my book. I would prefer to see them bash it out over months. Competing policies and ideas. The nomination process should be hard, deflating, difficult.

Getting the nomination should be difficult and painful and a months’ long slog through every, well, most of the states. There should be blisters and calluses. The process should painful for the potentials.

Locking in to one candidate too soon seems foolish to me.

I wasn’t born in Iowa, wasn’t raised here. I am definitely not a homer. The first year I was here was the run up to 2004. Bush was the default R, so all the attention was on the D potentials. Dean, Kerry, Edwards, Gephart. I couldn’t even vote. I was technically Minnesotan then.

I couldn’t vote and I got all of the endless, repetitive TV ads. In a average week I saw hundreds of political ad instances. I saw the same ad many dozens of times. It will and does drive you crazy. You learn to mute quickly.

What was I watching in 2003? Maybe Firefly. I would watch eight minutes of Firefly and fade to black and then six political ads in a row. It is crazy! And really [bleeping] annoying. I imagine it the same in New Hampshire.

We had the Westboro something Baptist somethings show up en masse downtown. They set up camp. I lived downtown. A block and half away. These were those idiots who sported about the “God Hates F*gs!” signs. I hated those mother[bleepers] so hard.

I am straight but I have friends and am not a monster. Westboro Baptist whatever can suck my [bleep]s. [Bleep] them!

One Saturday about 50 of us showed up to counter-demonstrate. That was so lovely!

Didn’t that entire church basically implode several years later when it came out the leader of that “church” was a unrepentant serial kiddy diddler?

@Chris:

I suspect that one vantage of the not-simultaneous primaries is that they permit a kind of almost “non-instant runoff voting” – usually after each primary the worst contenders quit, and in the next primary their potential voters will vote in one of the best positioned candidates, until only two candidates remain, and, in the end (usually much before the convention), only one.

@de stijl:

This is the mythology. I would suggest that it is more myth than reality.

First, US campaigns are already insanely long. It isn’t like we don’t get exposure to the candidates.

Second, the number of examples of some shining awesome candidate emerging from the crucible of the process is small. Indeed, I am not sure who would really, truly, qualify.

Third, along those same lines, how many times did it really, truly take a candidate well past SC (which is pretty damn early in the process) to really emerge?

Fourth, how often have we all really, truly changed our minds after seeing these folks battle it out in victory and defeats?

I could go on, but I just do not see a real argument for the grand use of this process as really, truly, helping get us better candidates (indeed, often the contrary) let alone really providing us with tons of useful information.

@Miguel Madeira:

Yes and no. Often the “worst” candidate in Iowa or NH might have down quite well in CA or TX. As a real filtering mechanism, it really isn’t great.

Iowa gave the GOP Huckabee in 2008, Santorum in 2012, and Cruz in 2016.

@Steven L. Taylor: There seems to be a pattern where the Republican candidate representing the hardcore so-cons wins Iowa. That was the case with Huck, Santorum, and Cruz–and probably Bush in 2000. (My guess as to why Bob Dole did so well there in 1988 and 1996 is because of his popularity among farmers. In 1980, when Bush Sr. beat out Reagan there, that’s the opposite of the pattern I described, as he was running as a social moderate whereas Reagan was clearly the candidate of the Christian Right. But that was before the modern evangelical takeover of the party emerged.)

In any case, the winnowing process is complicated. In 2008 eventual nominee McCain came out in fourth place, but was thought to have “won” that contest in terms of what he set out to achieve. He kept the expectations low for himself, and his main goal was that his leading rival, Romney, would fail to achieve 1st place. According to an inside report, on the night of the caucus McCain phoned Huck to congratulate him, and Huck told him, “Now it’s your turn to kick his butt.”

I do agree, though, that this is very much a media-generated process. Iowa is important not because of the delegates the candidates receive, but because of the story that gets told afterward. It’s kind of like the political version of crypto, its value is in what people ascribe to it.

@Kylopod: My point is that definitionally there are going to be localized effects on any given contest. To me that suggests that the myth that this is some grand crucible is just silly (to perhaps put too fine a point on it).