Are Electors Free to Choose?

SCOTUS and "faithless electors."

Anyone who has read this site for any amount of time is aware that I am a critic of the Electoral College. It is an ill-conceived institution that performs no defensible function superior to a popular vote. The best case to be made for the EC is that it has normally simply reflected the popular vote and therefore could be dismissed as no harm, no foul. Despite many public defenses of the EC it does not create some kind of special representation that balances large and small states nor does it produce regional fairness.

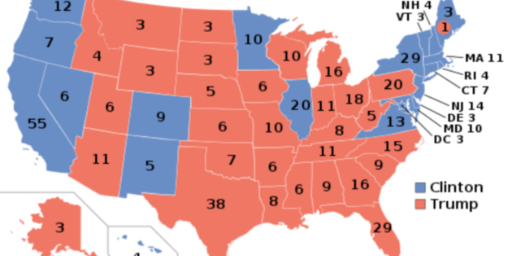

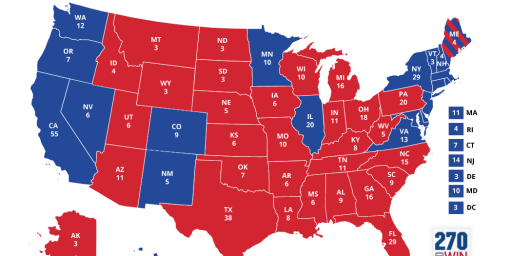

It is, quite simply, a system that gives more weight to smaller population states–it literally makes some citizens’ votes count more than others. And the distortions that that weighting creates has increased over time as the gap between largest and smaller population states have grown. Note, too, that the EC originally was based on the thirteen original states and did not conceive of vast states the size of Wyoming with barely any people in them nor behemoths like California or Texas (both in terms of area and population).

Moreover, it does not, as is often argued, give small states extra special attention in elections so that they don’t get ignored (nor do big states get special attention). No, swing states are the ones that get extra special attention.

As we all know, people in the states vote and the candidate who wins the plurality of the vote in each state wins a slate of electors. Each state is an electoral district with multiple seats. The plurality winner wins all the seats (the electors). Maine and Nebraska each have a state-wide district of two electors, and then have single-elector districts in each of their House districts.

Electors cast their ballots in their state capitols in December and those votes are counted in the US Congress in January.

Electors were originally intended to be independent actors and the US Constitution imbues them, not the people, with the power to elect the president. Article II, Section 1 states:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two Persons…

It is clear: the states appoint electors and electors vote for president and vice president. The people of the United States do not have any constitutional right to vote for president nor any guarantee they would have any specific role in choosing them.

It should be noted that the Framers thought that the electors would frequently be unable to have absolute majority agreement and therefore that the House would choose the President. This did not come to pass (happening all of twice and one of those was because of a design flaw that was later fixed). Instead, the EC quickly evolved from a deliberative body into a messenger system. The states would vote on a slate of electors to reflect that state’s preference for president and those electors would vote as a bloc. The usage of the popular vote to choose the electors evolved in the early-to-mid Nineteenth Century, meaning the plurality preference of the state became the whole state’s preference in toto.

Slates of electors have been selected by political parties, thus ensuring their loyalty to the plurality vote of the state. In every state in 2016 the Republicans choose their potential electors, the Democrats theirs.

Occasionally, an elector would deviate from the mission given to them. These have been termed “faithless electors.” They are rare and have never changed an EC outcome, but they potentially could (although the probability of such an outcome is near zero). Many states fine electors who do not follow their state’s will, others can replace the unfaithful. There is a case before the US Supreme Court about whether states can require electors to be faithful.

The Economist reports: America’s Supreme Court considers the rights of “faithless” presidential electors.

So-called “faithless” electors are rare, but nothing new. Ninety electors since 1796 have cast a ballot for someone other than their party’s elected nominee, including 63 who sought to replace candidates who had died after the general election. Some 27 electors have simply scrapped their pledged candidate in favour of another.

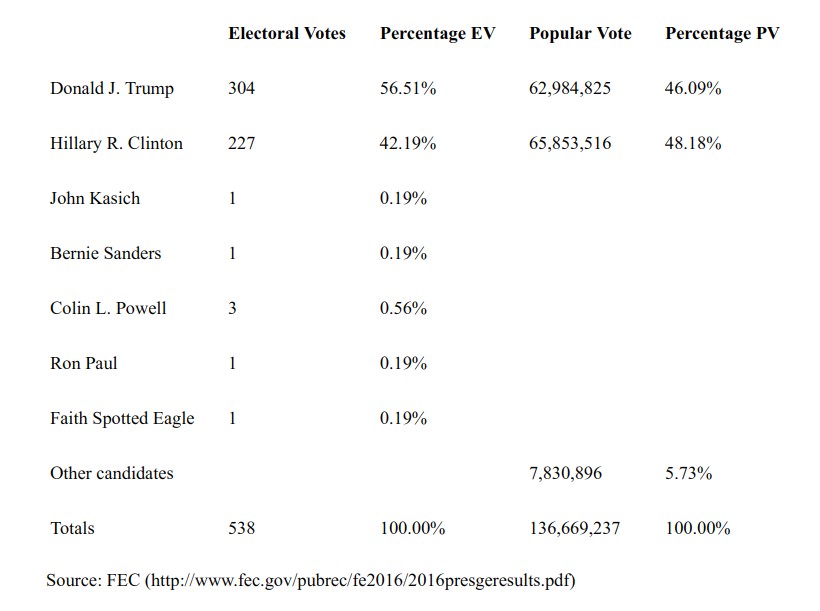

Let me note: really only 27 faithless electors over two-plus centuries, so not a massive problem. It should be noted that 2016 had an unusually high number of faithless electors. Note that “an unusually high number” was seven.

The results of some of the above-noted lack of faith had some consequences (back to The Economist):

Some defectors ran into legal trouble. Peter Chiafalo from Washington was fined $1,000 when he selected Colin Powell rather than Mrs Clinton in an attempt to throw the election to Congress. Michael Baca of Colorado found himself replaced with a more obedient elector when he tried to change his vote from Mrs Clinton to John Kasich, the former governor of Ohio. Both men say the constitution protected their right to do so.

It is my opinion that the Constitution clearly gives the vote to the electors and practice has reinforced this fact (Congress has always counted those votes). One could, perhaps, argue, that the state’s appointment power gives them control of the vote (but that strikes me as a weak argument–and why even have human beings as electors if they have zero agency?). I think, too, one could argue that states can fine the faithless but that the faithless vote still counts. I suppose that the appointment power could give states the right to replace an elector, as per the Colorado case.

Ultimately, given the partisan nature of the selection of electors, it is highly unlikely that an outbreak of faithless electors could change the outcome of an election. It is worth noting that most faithless electors are protest votes from the losing party. Five of the seven faithless electors in 2016 were Democrats. The two GOP examples of faithlessness are the real oddity. Both were from Texas, one vote for Kasich and the other for Paul.

Most elections have such a wide gap between electoral winner and electoral loser that the amount of faithlessness needed to swing the election would be unthinkable. Although an election like 2000 shows how it could matter, given that the final was 271 v. 266 (with one abstention, a Democratic protest).

At any rate, it will be interesting to see what the Court rules, but I don’t think it matters, ultimately. I cannot stress enough that the process of choosing electors is guaranteed to produce loyalists. There is no reasonable scenario in which electors as a group will ever act like a deliberative body. History and logic clearly demonstrate this. Whatever ruling the Court makes will be at the most marginal of the margin.

If we are really worried about faithful representation of the popular will, here’s an idea: just let the people choose their president like every other presidential democracy on the planet.

SCOTUSblog has more: Argument preview: Justices to weigh constitutionality of “faithless elector” laws

I occasionally play a game “If Madison could have seen 30 years into the future, what would he have changed?” I’m sure the Electoral College would be high on the list.

After the election in 2016, some of my friends were calling for the Electoral College to vote for someone else. While I knew there was no chance of it happening, I kept telling them that the only thing worse than a Trump presidency would be the Electoral College not voting him in.

@Kari Q: If Madison had had his way, Congress would have chosen the President (and the House would have chosen the Senate and Senate seats would have been based on population). If Madison had had his way, we would be better off in a huge number of ways.

This really seems like one of those things that are “norms” but not “rules” that we’ve heard so much about over the past few years. How long until this is weaponized?

@Tim D.: Part of my point is that it is really hard to weaponize this as it already under profound partisan control.

(And it is a combination of rules and norms).

@Steven L. Taylor: Yeah, I think that’s fair, but also we have seen a lot of creative weaponization over the past few years. Legal theories that seemed far out in orbit just a few years ago are getting respectful hearing at SCOTUS these days.

Like, what would stop a state from tacitly allowing (or refusing to fine or replace) a cadre of faithless electors who would throw the election in the direction they preferred?

@Tim D.: A fair observation.

@Steven L. Taylor: My fear of weaponization would look like this:

Just like Nebraska and Maine split their electoral votes, a couple of states (say Michigan, Pennsyvania, Ohio) get it into their heads to make their electoral votes proportional. But other states are winner take all. We could have unrepresentative minority rule for generations.

@Scott: That’s a different issue, and I agree it is a troubling scenario.

I am, in fact, adamantly opposed to the Maine and Nebraska model because it allows the EC to be gerrymandered.

I was referring solely to the unfaithful elector issue–which I what I took Tim D. to be referencing.

If I am reading The Constitution correctly and there is no guarantee of that, Article II, Sec. 1, Par. 2, Par. 4 and Amendment XII will all have to be scrapped and replaced with an Amendment that allows for the direct election of the President and Vice-President by eligible Citizens.

As far as I can tell the only way to make this change is noted in Article V.

Which method of Amendment do you think will accomplish this feat and how do we start today to get this moving?