Are we Finally Starting to Talk about Electoral Reform?

The NYT is trying to start a conversation.

Much of my ongoing writing about the quality of US democratic institutions is aimed at trying to get us all to at least understand that there is a debate to be had that goes beyond “this is the way we have always run elections, therefore there is nothing to talk about.” Additionally, it has been clear to me for some time, and especially of late, that an electoral system that does not produce a reasonable fit between votes and seats is not tenable in the long term. This is especially true in the context of highly polarized parties because it means that if the system is favoring one group over the other, and the group being favored in the one will less popular support, then that is going to be noticed and will fuel anger and resentment against both the opposite party as well as against the system itself.

Much of my ongoing writing about the quality of US democratic institutions is aimed at trying to get us all to at least understand that there is a debate to be had that goes beyond “this is the way we have always run elections, therefore there is nothing to talk about.” Additionally, it has been clear to me for some time, and especially of late, that an electoral system that does not produce a reasonable fit between votes and seats is not tenable in the long term. This is especially true in the context of highly polarized parties because it means that if the system is favoring one group over the other, and the group being favored in the one will less popular support, then that is going to be noticed and will fuel anger and resentment against both the opposite party as well as against the system itself.

Those who study democratic institutions have long understood the representation problems with US institutions that diminish (or thwart) representative outcomes in our elections. Indeed, I ran down a list of some of them just a few weeks ago. As I said in that post:

our current system doesn’t do a very good job of representing the population and of late has put us in a position of minority rule. This affects all three branches of the federal government. I know that many see this observation as a partisan point, since the systematic advantage goes to Republicans over Democrats. However, the concern here is not about party, but about the long-term health of the system as well as a concern for basic fairness and the fact that, as a general proposition, a representative democracy is supposed to be representative of the people in some significant fashion.

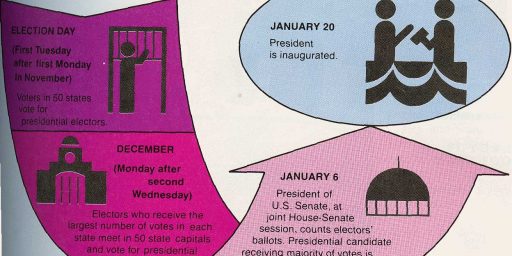

These are not new issues. What is new is that they are becoming harder to ignore. The easiest example is the Electoral College, since it has produced a popular vote loser as president two out of five times of late. Other issues have been growing: the way in which technology has made gerrymandering single seat districts easier (whether at the state or national level) and a growing recognition of what the math of the Senate does to representation (and to things like judicial appointments, especially to SCOTUS).

In our book that compared the US to 30 other democracies each chapter had a list of ways the US deviated from its democratic brethren. In the chapter on electoral system we noted a remarkable lack of popular criticism or discussion about our plularity-based electoral system in the United States. This was in contrast to the UK and New Zealand. The UK still uses first past the post (FPTP), single-seat districts to elect the House of Commons, but there has been a debate in the country for decades over its shortcomings. Indeed, there was a referendum to adopt the alternative votes (instant run-off) in 2011 (it failed). In New Zealand, FPTP was replaced in the 1990s with mix-member proportional system (usually just refereed to as “MMP”).*

In the US we usually get crickets on this topic, or dismissiveness. Indeed, the usual response when one points out that there is a serious disjuncture between the popular vote and the seats won because of that vote, is some variation of denial that that popular vote metric matters (I would, in respectful-disagreement mode, put James Joyner’s recent post in that category).**

Now, at least, we might be starting a more serious national discussion (although I am no Pollyanna in terms of how serious, let alone how widespread). As the saying goes, a journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step, and we have recently seen some tentative steps in this discussion (usually around the EC). Now, maybe, we are starting to take about the House. I take two connected op/eds in the NYT to be important parts of the first few steps needed: America Needs a Bigger House and A Congress For Every American. Both pieces are worth reading in full.

The first focuses on perhaps the easier reform to make (although still not an easy one): expanding the size of the House (which can be done via statute).

A key element to note:

There’s no constitutional basis for a membership of 435; it’s arbitrary, and it could be undone by Congress tomorrow. Congress set it in 1911, but following the 1920 census — which counted nearly 14 million more people living in the United States — lawmakers refused to add seats out of concern that the House was getting too big to function effectively. Rural members were also trying to forestall the shift in national power to the cities (sound familiar?), where populations were exploding with emigrants from farm country and immigrants from abroad.

In 1929, Congress passed a law capping the size of the House and shifting responsibility for future reapportionments onto the Commerce Department. That’s why, more than a century later, we find ourselves with a national legislature far too small to fairly represent both the size and diversity of modern America. This warps our politics, it violates basic constitutional principles of political equality, and it’s only getting worse.

Indeed, it is actually pretty stunning to note that the current House was set when the population of the US was ~92 million. Read that sentence again and let it set in. In the abstract almost anyone would assess that fact as near insanity.

Now, the article remains focused on FPTP in single seat districts (the second moves off that point).

One weird aspect (in bold) of the editorial’s proposed seat count for the House is this (which will only resonate with electoral studies geeks such as myself):

There’s a better solution, which involves bringing America into line with other mature democracies, where national legislatures naturally conform to a clear pattern: Their size is roughly the cube root of the country’s population. Denmark, for instance, has a population of 5.77 million. The cube root of that is 179, which happens to be the size of the Folketing, Denmark’s parliament.

This isn’t some crazy Scandinavian notion. In fact, the House of Representatives adhered fairly well to the so-called cube-root law throughout American history — until 1911. Applying that law to America’s estimated population in 2020 would expand the House to 593 members, after subtracting the 100 members of the Senate.

I don’t understand the argument that one would include the Senate in the assembly size calculation of the House. The Cube Root Rule should be applied to the House only. I see no logical reason to include the second/federal chamber in that calculation. Indeed, an eye-balling of the chart in the piece indicates that they didn’t treat other bicameral systems as one unified assembly for this purpose (the UK and Colombia numbers are definitely for the first chamber only).

BTW, if one is a hardcore original intent adherent, note that if we has stuck with the Framers’ vision, each district would be 30,000 residents and the House would have 11,000 members (have I ever noted that there is no way the Framers could have conceived of a continental country of over 300 million people?).

The second op/ed goes beyond just expanding the House to look at moving away from single seat districts.

Most people don’t question the wisdom of voting for only one member per district, if they think about the matter at all. But there’s nothing special or preordained about it. In fact, the alternative — districts that send multiple members to Congress — was the norm at the nation’s founding. Nine states still use multimember districts to fill at least one state legislative chamber, and four — Arizona, New Jersey, South Dakota and Washington — elect all their state lawmakers this way.

The piece goes on to make a case for rank choice voting (RCV) which is basically the alternative vote for multi-seat districts (and is also called the single transferable vote, or STV).

The piece notes:

By FairVote’s calculations, it’s possible to draw multimember districts in all but the seven states that have only one representative. The remarkable thing is that every district in the country with three or more members would have representatives from both major parties. In other words, America isn’t as politically segregated as most people think; it only looks that way because of our zero-sum, winner-take-all elections and the political maps that reflect them, portraying vast sections of the country as entirely red or blue.

This is worth under-scoring: the red/blue dichotomy is largely an artifact of the binary choices voters are given. Almost everywhere is actually purple to one degree or the other (i.e., most areas are not solidly R or D). Such a system would also encourage third party formation, as the threshold for wining a seat ceases to be the plurality in a single seat district.

Again, read the whole piece and give it some thought. I am just pleased to see real electoral reform being discussed intelligently in a national forum.

The piece concludes as follows, which is good place for me to stop as well (referring to the combination of an expanded House and RCV in multi-member districts):

The result of all this is that the vast majority of voters, whether they live in cities, in suburbs or in rural areas, would have someone in power who represents them. This could help foster bipartisanship and compromise, as members of different parties would need to work together on behalf of their district’s voters. After all, both Democrats and Republicans need the potholes to be fixed.

Add in a larger House of Representatives, and you increase the opportunities for voters to be represented more in line with their numbers in society.

And that’s the whole point. When citizens feel that their voice is being heard by government, they’ll be more eager to participate, more likely to vote and more politically engaged overall. That’s what a democracy should look like — and in the long run, it’s the only way a democracy can survive.

I will say that I am not sure I buy that this would “help foster bipartisanship and compromise” necessarily (there is something about major US newspapers that require their op/eds to fantasize about bipartisan harmony), but it would increase represenativeness, which I think is sorely needed in our politics.

*If you would like a simple primer on MMP, which is one of my preferred systems, see this video.

**I especially took issue with “meaningless” and “silly metric.” I know he and I have a general philosophical agreement that our system has representation problems, but I think that post goes overboard on this issue. I need to write an actual response at some point soon). And to be fair: in the abstract he is in favor of reform (even something dramatic like abolishing two seats per state in the Senate). I just think he is mistaken to so easily dismiss the information provided by the popular vote totals for the House.

I agree that this is an important issue, but I really dont see it changing. Every conservative I have talked with about this does not see it as a problem. They are winning even with fewer votes so they dont want to change anything.

Steve

I’ve been following with interest the race in Maine’s 2nd district, because it’s become a testing ground for Maine’s new ranked-choice system it recently adopted. The Republican incumbent, Bruce Poliquin, has a slight lead in number of votes, but well below an absolute majority and with more than 8% of the vote going to two independent candidates. Exit polls indicate that an instant runoff with the indie candidates will benefit the Democrat (Jared Golden), and it looks likely that Poliquin will legally challenge the results if they turn against him.

@steve: Change is hard (and improbable). I do think that if current representation distortions continue there will be change one way or another.

Regardless, I would strenuously state that the issue should not be whether it is a likely or not, but whether it is the right thing or not. The response that it is hard, and so why talk about it just guarantees there will be not change.

Not sure this is true as Republican voters in Misery have time and again refused to pay to have those potholes fixed, including in this most recent election.

As to the meat of your post Steven, I certainly agree the status quo is not sustainable and that expanding the House is the least we can do. However, right now we can not even agree on who should be allowed to vote.

For instance, Republicans in GA have decided that the franchise should be restricted to people who only sign their names in exactly the same fashion every time. Here in Misery, it has been decided that some poor urban people should have to stand in line for as much as 4 hours in order to exercise their right to vote but rural voters can do it in 15 minutes or less. This election it took me less than 10 mins, start to finish. Back when I lived in STL I don’t think it ever took me more than an hour and half, maybe 2, but every election I read of some polling places having lines that go around the block (the rain falls on poor and rich alike but somehow or other the rich have much shorter lines) and with absolutely egregious waits.

We need a voters bill of rights too.

If people discovered that a pure Proportional Representation Model(A la Brazil) is a bad idea, then the debate is really going on in a good way.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Could you explain why increasing the size of the House is the “right thing” to do to solve our country’s representation problem versus seeking ways to neuter gerrymandering or some sort of Senate reforms?

I’m completely with you on the need for reform, I’m just sympathetic to the argument that a much larger House would be harder to manage effectively, plus there are much better things I’d like the nation to spend money on over Congressional salaries.

Joyner tends to be very conventionalist in his thinking. The rules are the rules, and they should be obeyed purely because they’re the rules, and if anyone thinks the rules should be different, well then they’re just a silly, crazy person.

@Scott F.:

Not to be snarky but, we are currently managing a country (despite trump) of 325+ million people. I think we can handle 500 or 600 hundred representatives.

@Scott F.:

Steven can do this far more technically, but let me take a swipe. Taking steps to remove partisan gerrymandering should enable each district to become more representative of it’s local population. However, fixing gerrymandering does not address that (provided our population continues to grow) the cap ensures that more densely populated areas of the country will lose representational power.

Yes, less densely populated states will lose representatives, but not at a rate that adequately solves for the lack of representation in more densely populated states (or rather densely populated areas within those States). The net result is that rural areas and States will wield unequal/greater power. And, provided that we continue down the rural/urban schism/realignment, that only increases the possibility of minority majority rule.

BTW, the Wikipedia page on this issue is honestly not that bad: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_congressional_apportionment#Controversy_and_history

@OzarkHillbilly:

Not to be snarky, but the House at its current count is hugely dysfunctional. What about being larger would change that, especially if we remain with just two parties?

As I stated, I’m earnestly in favor of reform. But, I’m interested in better government, not just different government. Reforms that exacerbate our governance issues wouldn’t head us in the right direction.

@Scott F.:

The basic answer is that the smaller that House (and the larger the number of citizens being represented) the more likely that urban voters will be packed in homogeneous districts or have their voting power diluted by connecting them to rural populations. Put it this way: the most representative system would be one of each of being a representative. As districts represent more and more residents, the more specific interests get diluted.

The least representative system is one with only one representative for everyone. The trick of representative democracy is finding the balance between 1:1 and 1:everybody.

Think also about this: without getting into details, the reality at moment is the Dems need at least 55% of the popular vote to win the House, while the Reps can win it with less than 50%. This is partly because of gerrymandering, but it is more about geographic sorting. More representatives would better capture the balance of the vote. The system should reasonably produce an outcome in which two party competition leads to a party with 50% of the national vote should get close to 50% of the seats.

Also: it is really important to stress that while gerrymandering can be made less problematic, it cannot be neutered. Our fundamental problem is to be found in the effects of single seat districts themselves.

@Scott F.:

Part of House dsyfunction is a function of its lack of represenativeness. Note that the party that doesn’t want to govern has a built-in advantage in the current structure.

@Scott F.: Steven answered here @Steven L. Taylor: at least as well as I could have. I’m not saying it’s a cure all (as I pointed out, ensuring that ALL eligible voters have their votes count is a minimum) but it’s better than 435 for 325 million.

@Scott F.:

The House is supposed to be reflective of the population ie if they are numerous, so should the number of representatives. The artificial number imposed on the House is from a CENTURY ago and even then it was intended to impose “order” by sacrificing cities’ representation (where immigrants were more likely to live) in favor of rural control. Limiting House representatives has always been about keeping down more populous areas and concentrating power in limited areas. It goes against Founder intent as the Senate was supposed to be the means for smaller states / populations to maintain against the tyranny of the *majority*; the House was part of the compromise that was to do the opposite and protect against the tyranny of the *minority*.

Given that the modern Republican Party has put party and partisan advantage above the country as a whole, I don’t see a lot of opportunity to create real change unless they feel they have had elections and representation stolen away from them.

The recounts in Florida might (if we are lucky) provoke enough outrage that we will get federal legislation to address that — some kind of grand bargain involving counting and recounting rules, along with voter rights. Putting a numerical limit to the number of people in a polling place and a counting area would go a long way to ensuring timely and transparent elections. I would trade voter id for early voting, and a requirement that valid id be made easily available (and ancient populations be grandfathered in, as their documentation might be hard to get). Rules around voter roll purging.

As far as expanding the House goes, we would have to get the disenfranchised conservatives in Los Angeles to get angry.

@Stormy Dragon:

There are two, completely distinct, arguments that I make with regard to the issue, only one of which was the subject of that particular post.

1. The rules are the only thing that matters in terms of the legitimacy of the outcome. That is, Trump’s winning the presidency despite getting 3 million fewer votes than his opponent points to a serious need for institutional reform but it doesn’t make his victory illegitimate. Everyone knew the rules going in and the contest was run according to those rules.

2. The subject of the post in question, though, was something much narrower: whether it makes any sense to judge the national intent by aggregating a lot of separate elections. Because those votes are idiosyncratic, I don’t think we can extrapolate from that metric. My argument isn’t “the rules are the rules” —Steven and I agree that the rules are in desperate need of change— so much as whether a particular post hoc statistic is a meaningful indicator. And I think we already have better indicators. In the comments above, @Steven L. Taylor observes:

That strikes me as the real issue and I just don’t see how aggregating individual races with different stakes and circumstances provides better insights. Steven is an expert in electoral systems and disagrees, so I’m amenable to being convinced on the topic.

While I think Dr. Taylor’s idea of expanding the size of the House has some merit (it’s certainly better than the mess we have now), what I’d like to see before doing that is this: Passing a law that sets up an independent commission to draw congressional districts in every state. While the Constitution probably bars such federal intervention in state legislative reapportionment, I see no constitutional barrier to having the federal government control the way in which congressional districts are set up.

@SC_Birdflyte:

There is precedent for that. The voting rights act mandates the creation of districts where a minority gets majority representation. I see no problem, then, with a federal law mandating districts be competitive, regardless of the means used in drawing them.

If gerrymandering into district shapes that a jigsaw puzzle maker couldn’t imagine up, trueing up the seat distribution to actual population, and elimination of senseless voter suppression methods was accomplished, structural change would be far less necessary.

Why the system had states determine the rules for federal elections is simply beyond me.

@SC_Birdflyte:

Look, that is better than what we have now, which is a lot of lines being drawn by people with partisan motivations.

But I cannot stress this enough: there really is no such thing as a set of single seat districts that are going to be fully neutral and utterly fair. Varying population density alone will mean that to some degree the containers are more important than what they contain.

If the goal is representation, then the system has to go to multi-member districts.

@James Joyner:

I will see what I can do 😉

I will agree that the metric is imperfect, I just think it rises to a level well beyond worthless to tell us something about the overall system.

If I could design the ideal structure for a lower house, it definitely wouldn’t be anything like the one used not only in the USA but most other democracies, where the whole body consists of one representative from each of a set of geographic regions. No matter what, you’re going to have a lot of failures in representation, because people don’t conveniently arrange themselves into groups that would select a representative set of themselves. By contrast, STV enables nearly all voters to be able to point to one specific elected official as “theirs” in the sense of both representing their community and having received their vote.

As a simpler alternative, mixed-member proportional representation (which, as a bonus, shares its initials with the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers) allows both those features, but not necessarily as combined in one legislator. Instead, you and your neighbors get a specific representative to call on the phone and the assembly as whole reflects the country’s partisan makeup by the use of added seats, typically a number equal to the set of geographically-elected seats.

I have my own personal notion of how the Senate ought to work, but it’s not Constitutionally possible because of the “equal suffrage with their consent” clause. Still, setting that aside, I admire the notion of William Simon U’Ren, whose activism was a major contributor to the fact that we now elect Senators directly. He additionally proposed for his own state of Oregon a system whereby each rep would have the power to cast legislative votes equal to the number she or he had received in the last election. Additionally, each party’s candidate for governor would participate in those votes with a power equal to the set of votes cast for losing candidates of their party. In this way the total number of “votes” in the assembly would be equal to the number of voters (rather than some members benefiting from having faced unpopular contenders) .

My own modification to this would be to change the voting system to a range/approval method: For every single Senate candidate, you can mark that you like, dislike, or are neutral about them. The winning candidate is the one with the highest net approval, and they enter the Senate with that net approval as the “size” of the vote they can cast. If all the contenders were more unpopular than popular and hence had a negative total, the “winning” candidate would have their power rounded up to zero, which would make them a mere observer and non-participant, which is exactly the sort of “representative” that US territories elect to the House.

This possibly-absurd system would still give senators equal representation in the number of participants in debates, and perhaps the unequal voting power would be waived for some simple procedural votes. (I also believe each state should have three rather than two senators, so that the “classes” of jointly-elected senators would always consist of one from every state. That’s partially because of OCD but mostly because the third of the Senate up for election should be less arbitrary and enable more of a sense of the national attitude.)

@James Joyner:

This is precisely the point I’m critical of: the idea that rules, regardless of their content, create legitimacy purely by being rules. That legal positivist sort of idea is very typical of your way of viewing the world. Which is fine, as far as it goes, but you also seem to think they’re some sort of universal axiom that everyone else is required to buy into.

Steven, while I acknowledge your expertise in this area, I’m going to argue from my more limited knowledge that MMP, or any such system, has the opposite effect than you intend, i.e. that it is less proportionally representative than our current system. If I look around at countries with a strong party system, I see either a) Countries like Italy where the huge number of parties make it virtually impossible to form a stable government, or b) Countries like Israel where small, extremist parties enjoy strangleholds over the majority due to their necessity in forming governments. In the Israel example, religious extremists comprising 5-10% (several small parters acting collectively) have won concessions on marriage (only rabbis from certain religious extremist sects can decide who is a “legitimate” jew and therefore who can get married and divorced), on the settlements, on paying religious extremist men not to work (because they are enrolled in religious “schools”), on whether a woman can take any available seat on a bus, and so on.

I suppose the minimum 5% rule might keep some of this from happening, but I am not optimistic. Or do you feel there are MMP countries that have not descended into either A or B above?

@MarkedMan: There is a lot to unpack here.

First, neither Italy nor Israel uses MMP. Prior to 2006 they used MMM (Mixed Member Majoritarian) and have used bonus-adjusted PR since. Israel uses a highly proportional closed-list PR system in one national electoral district.

The main MMP examples are Germany and New Zealand.

Second, “has the opposite effect than you intend, i.e. that it is less proportionally representative than our current system.” I think there is some confusion here. At a minimum, what you are complaining about in regards to Israel is that it is too proportional in its outcome.

Third, you have picked the examples that are pretty typical in the anti-PR argument, but you are ignoring that most of the democratic world uses some system different from FPTP. In other words, there is a much wider world for comparison and I would never use either of these cases as the ones to emulate.

MMP is a system I like because it produces nationally proportional outcomes, but also local representation and does so without the crazy fragmentation of something like Israel.

It isn’t perfect, btw, but nothing is.

Huh? By what metric?

Quick note. one of the articles mentioned the GOP has a seat bonus. And that the democrats used to have it prior to 1994. This may be a problem because 1) both parties will want to (re)capture the bonus, 2) both parties can complain the other is in favor of reform only when it’s out of power.

@Catchling: Most countries do not use single seat district, first past the post elections. The main cases that do are the US, the UK, Canada, and India. France and Australia use single seat districts for their first chambers, but not with FPTP.

Apart from France and the UK, I think the rest of Europe uses some system other than FPTP and the same is true of all of Latin America (excluding the Caribbean). Japan and Korea use MMM. I forget what Taiwan uses.

This is off the top of my head, so I may be forgetting something.

The reality is that the US’ electoral system is well outside the global democratic norm.

@Kathy: Parties will always argue for the system that benefits them. That is a given.

Note that pre-1994 the Dems had advantages because Reps were still non-competitive in the South.

Indeed, the real difference is whether the majority party had the bonus (pre-1994) or if the minority party does (now).

@Steven L. Taylor:

It is. That’s what makes reform so hard, when, however much they may be oppose d in every other respect, both want to maintain the status quo.

We’re approaching the Einstein insanity zone: both parties keep doing the same thing, hoping for a different result.

@MarkedMan: I guess I wasn’t clear enough. By lack of proportionality I meant the power over actual policies. In Israel very small parties comprised of religious extremists have wielded incredible power over the very real everyday life of millions of people, because of the coalition building necessary to forming a government.

And I understand that they are a not an MMP system, which is why I was asking what in MMP would make such an outcome unlikely. Do you feel the 5% rule is sufficient in and of itself that any party must at least nod towards inclusivity and thereby diminish in extremism? Or are there other mechanisms?

@MarkedMan:

The simple answer (which is quite inadequate) is that the nature of the nature of the rules chosen (both the broader system and the specific elements therein) can influence the degree to which really small parties can be successful. All systems have a threshold, although not all are in law (the math of a given system always create some kind of threshold). Germany does have a 5% legal threshold to try and forestall extremist parties.

Granted, some of these issues are based on a given political culture and historical circumstances, so you can’t guarantee lack of extreme politics.

Note that “proportional” has a very specific meaning in electoral studies. A perfectly proportional electoral system is one in which the percentage of seats a party wins in the legislature is equal to the percentage of votes it receives. There is always some deviation between those numbers, and that deviation is called disproportionality.

Israel’s system is extremely proportional. A party can win less than 5% of the voteand still win a seat in the Knesset. (This is not a legal threshold, but math eventually limits outcomes depending on a number of variables).

Note: edited and expanded for clarity.

@Steven L. Taylor: Thanks for the clarification. How about Italy? They seem to be consistently unable to form a lasting government. Do they have a 5% rule or something similar?

@MarkedMan: Italy is more complicated (in more ways than one). In fact, their rules have shifted over time. Italy may just be Italy–although I think that the focus on government formation (or, more accurately, the number of governments they have had) exaggerates the problem. In other words, while the number of Italian governments is often used as a tale to shoot down PR and parliamentary government, I am not sure that the caution it suggests is an dire as it sounds. But even if we take the cautionary tale at face value, Italy is an outlier.

@MarkedMan: BTW: I edited and expanded my initial response from this morning–I wrote it in a hurry and it was incomplete/a tad confusing.