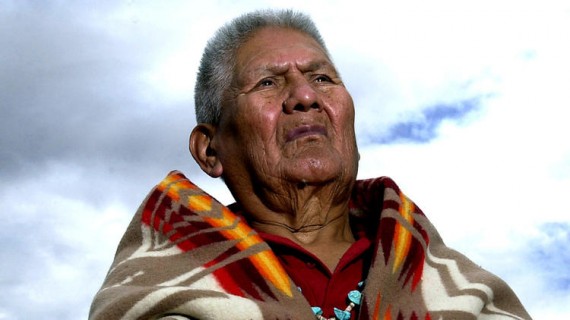

Chester Nez, Last Of The Navajo Codetalkers, Dies At 93

Chester Nez, the last of the original Navajo Codetalkers, a group of Native Americans who provided a vital communications tool to the American military during World War Two, and a recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor has died at the age of 93

The final member of the original Navajo code talkers, the group of 28 Native Americans who played a crucial role for U.S. communications during World War II, has died.

Chester Nez died Wednesday in Albuquerque, confirmed Judy Avila, who helped Nez write his memoirs.

Nez was 93.

Nez, among the first recruited, helped to develop code based on the Navajo’s unwritten language. The code thwarted the Japanese trying to intercept American communications in the Pacific during World War II.

The 2002 John Woo film “Windtalkers” brought the story of the code breakers to the big screen.

In his memoirs, Nez said he knew he made the right decision to join the fight.

“I reminded myself that my Navajo people had always been warriors, protectors,” he said. “In that there was honor. I would concentrate on being a warrior, on protecting my homeland. Within hours, whether in harmony or not, I knew I would join my fellow Marines in the fight.”

The 2002 John Woo film “Windtalkers” brought the story of the code breakers to the big screen.

In his memoirs, Nez said he knew he made the right decision to join the fight.

“I reminded myself that my Navajo people had always been warriors, protectors,” he said. “In that there was honor. I would concentrate on being a warrior, on protecting my homeland. Within hours, whether in harmony or not, I knew I would join my fellow Marines in the fight.”

The death in 2011 of Lloyd Oliver made Nez the last surviving member of the unit.\

More from the Associated Press:

Nez was in 10th grade when he lied about his age to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps not knowing he would become part of an elite group of Code Talkers. He wondered whether the code would work since the Japanese were skilled code breakers.

Few non-Navajos spoke the Navajo language, and even those who did couldn’t decipher the code. It proved impenetrable. The Navajos trained in radio communications were walking copies of it. Each message read aloud by a Code Talker immediately was destroyed.

“The Japanese did everything in their power to break the code but they never did,” Nez said in the AP interview.

Nez grew up speaking only Navajo in Two Wells, New Mexico, on the eastern side of the Navajo Nation. He gained English as a second language while attending boarding school, where he had his mouth washed out with soap for speaking Navajo.

When a Marine recruiter came looking for young Navajos who were fluent in Navajo and English to serve in World War II, Nez said he told his roommate “let’s try it out.” The dress uniforms caught his attention, too.

“They were so pretty,” Nez said.

About 250 Navajos showed up at Fort Defiance, then a U.S. Army base. But only 29 were selected to join the first all-Native American unit of Marines. They were inducted in May 1942 and became the 382nd Platoon tasked with developing the code. At the time, Navajos weren’t even allowed to vote.

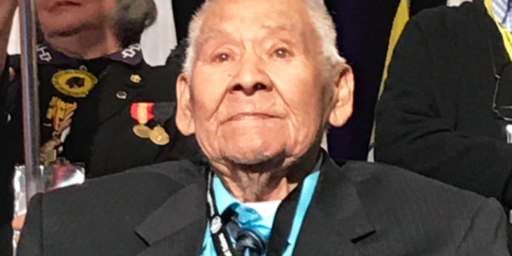

After World War II, Nez volunteered to serve two more years during the Korean War. He retired in 1974 after a 25-year career as a painter at the Veterans Affairs hospital in Albuquerque. His artwork featuring 12 Navajo holy people was on display at the hospital.

For years, Nez’s family and friends knew only that he fought the Japanese during World War II.

Nez was eager to tell his family more about his role as a Code Talker, Avila said, but he couldn’t. Their mission wasn’t declassified until 1968.

U.S. Sens. Tom Udall and Martin Heinrich, and Rep. Ben Ray Lujan, of New Mexico, praised Nez for his bravery and service to the United States in a statement Wednesday. The Code Talkers took part in every assault the Marines conducted in the Pacific, sending thousands of messages without error on Japanese troop movements and battlefield tactics.

Once while running a message, Nez and his partner were mistaken for Japanese soldiers and were threatened at gunpoint until a Marine lieutenant cleared up the confusion. He was forbidden from saying he was a Code Talker.

“He loved his culture and his country, and when called, he fought to protect both,” Udall said. “And because of his service, we enjoy freedoms that have stood the test of time.”

The Codetalkers were among the most valuable members of the units they were assigned to, to the point that they were each assigned a Marine whose primary duty was to guard them, keep them alive, and most importantly, prevent them from being captured. Obviously, the fear was that if one of the Navajos was captured, the Japanese would be able discover their secret and break a code that was otherwise impossible to decypher with existing technology. Some versions of their story say that the guards were under orders to kill the Codetalker if that was the only way to prevent them from falling into enemy hands, which may have been the most merciful thing to do given the torture that the Japanese would have likely subjected them to in order to break the code. Fortunately, none of the men ever fell into enemy hands and the code remained unbroken throughout the entirety of the war in the Pacific Theater.

It’s ironic, of course, that someone from an ethnic group that has been treated so badly by Americans should serve such a vital role in defense of the nation, and in that regard the Codetalkers are joined by the Japanese Americans who served their nation with honor and distinction in the European Theater, most notable among them being former Senator and Congressional Medal of Honor winner Daniel Inyoue. They deserve thanks for their service, and for the dignity with which they undertook their jobs.

“It’s ironic, of course, that someone from an ethnic group that has been treated so badly by Americans should serve such a vital role in defense of the nation”

That’s one of the reasons the picture has always deeply resonated with me. The Marine on the far left, as if reaching for the flag of his nation that beyond his grasp, is Ira Hayes, a member of the Pima tribe.

What a hero. Simply said. The young men today could learn so much from the example of those brave yet humble Code Talkers.

Great little poem on youtube for those who don’t have time to read the whole story-

Bob Welsh- The Navajo Code

Maybe all those folks who want to force US Citizens to speak English should eat some soap themselves. I’m thinking of you Rickey Dink.

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/election-2012/rick-santorum-puerto-rico-state-speak-english-article-1.1039479

@ernieyeball:

One of the great ironies is at the same time these Navajo men were helping win the war using their native language, countless Native American children were being more or less forced into so-called Native American Boarding schools where the language and cultural practices were systematically stamped out of them in the name of making them “more American.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_assimilation_of_Native_Americans