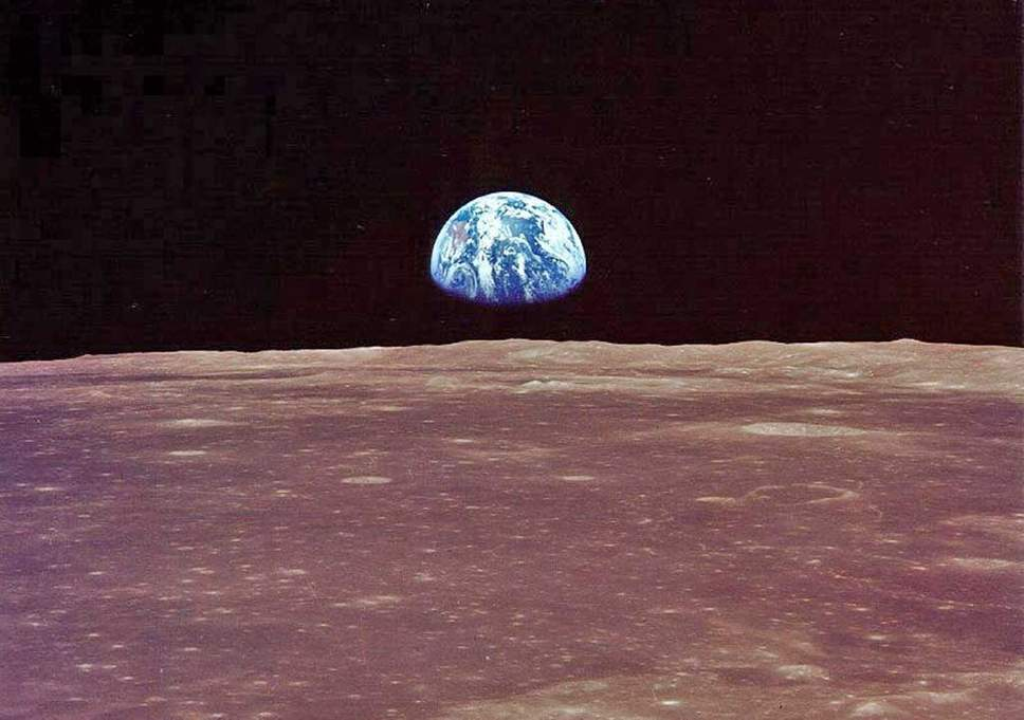

Earthrise 50 Years Later

Fifty years ago tonight, one of the most iconic photos in history was taken.

Fifty years ago today, the astronauts of Apollo 8, Frank Borman II, James Lovell Jr, and William Anders, became the first manned spacecraft to leave Earth’s orbit, orbit the Moon, and return home safely. It was, quite obviously, an important moment for the Apollo program that ultimately led to the landing of Apollo 11 on the Moon just seven months later. During the course of that mission, as the three astronauts spent Christmas Eve alone in a spacecraft orbiting Earth’s only natural satellite, they took one of the most stunning photographs in human history, the photo of the Earth rising above the Lunar surface which has come to be known as “Earthrise”

Picture the Earth from space: the striking bright blue of the oceans, the swirls of white clouds. It’s really very easy for any of us to conjure this image in our minds today, but it wasn’t always so.

The Earth in all its splendid majesty was seen for the first time on Christmas Eve 50 years ago, when it was captured in an image that changed not only the way we think about space, but how we think about Earth and our place in the universe.

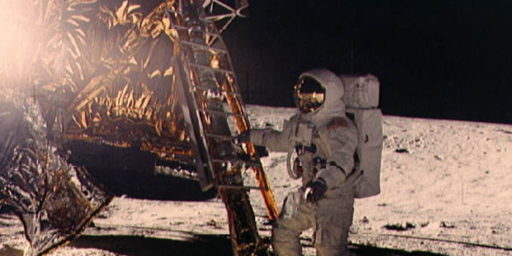

The picture was taken in the midst of the space race. Major William A Anders and the rest of the crew aboard the Apollo 8 mission were keenly aware of the pressures of their mission to orbit the moon, laying the groundwork for the first lunar landing that was still to come.

A few years back, speaking at the Johnson Space Center as part of a BBC documentary on the mission, Anders recounted the experience. As they ascended into space he snuck a glimpse of Australia, he said. He tried to peak at his hometown of San Diego but it was covered by fog.

Once they were a safe enough distance from Earth for further sightseeing, Anders perceived the glowing orb in the distance behind him, but the enormity of it didn’t register.

“That’s when I was thinking ‘that’s a pretty place down there,'” Anders said. It was “kind of like the classroom globe sitting on a teacher’s desk, but no country divisions. It was about 25,000 miles away where you could still recognize continents.”

After two to three orbits around the moon, he and the crew began shooting photographs.

“I don’t know who said it, maybe all of us said, ‘Oh my God. Look at that!'” Anders said.

“And up came the Earth. We had had no discussion on the ground, no briefing, no instructions on what to do. I jokingly said, ‘well it’s not on the flight plan,’ and the other two guys were yelling at me to give them cameras. I had the only color camera with a long lens. So I floated a black and white over to Borman. I can’t remember what Lovell got. There were all yelling for cameras, and we started snapping away.”

Earthrise – the name given to Anders’ iconic picture, one of the most lasting and memorable in the history of space travel, if not human history itself – would come a little bit later.

Looking back on it year’s later, Frank Borman, the mission’s commander, said words failed him and his crew in the moment.

“I don’t think we captured, in its entirety, the grandeur of what we had seen,” he’s said.

On Christmas Day in the New York Times, the poet Archibald MacLeish, who like everyone else still on Earth had only as yet seen images broadcast on television black and white, put himself in the astronauts’ seats, attempting to capture the awe of what the Apollo 8 crew other astronauts would later experience, and has been called the “overview effect”.

“To see the Earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold – brothers who know now they are truly brothers.”

Suddenly Earth no longer seemed the center of the universe, he wrote. Logically of course many people had long known this, but Anders’ photograph had a way of confirming it.

Writers and dreamers and scientists would return to that feeling of celestial displacement often over the years. In a 1983 short story Human Moments in World War III, Don DeLillo places a character in Anders’ viewpoint.

“The view is endlessly fulfilling,” he wrote. “It is like the answer to a lifetime of questions and vague cravings.”

After the mission was complete the photo would go on to grace the final issue of Time Magazine of the year, with the caption: “Dawn.”

As it turns out, the Apollo 8 crew almost missed its chance to take the picture, as the video re-creation below explains:

The Washington Post has more:

The astronauts had spun around the moon a few times already, their gaze pointed down on the gray, pockmarked lunar surface. But now as they completed another orbit of the moon on Christmas Eve 1968, Frank Borman, the commander of the Apollo 8 mission, rolled the spacecraft, and, soon, there it was.

Earth, this bright, beautiful sphere, alone in the inky vastness of space, a soloist at the edge of the stage suspended in the spotlight.

“Oh, my God,” exclaimed Bill Anders, the lunar module pilot. “Look at that picture over there! There’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!”

Anders knew black and white film wouldn’t do it justice. But he also knew he didn’t have a lot of time if he was going to get the shot.

“Hand me a roll of color quick, will you,” he said.

“Oh, man, that’s great,” said Jim Lovell, the command module pilot and navigator.

“Hurry,” Anders pleaded. “Quick!”

Anders loaded the color film into his Hasselblad camera and started firing away while his anxious crewmates remained transfixed by the blue and white vision outside their windows.

“You got it?” Lovell asked.

He did.

It wasn’t until days later, though, that they got to see what Anders had captured at just the right moment:

Two days later, the film was processed, and NASA released photo number 68-H-1401 to the public with a news release that said: “This view of the rising earth greeted the Apollo 8 astronauts as they came from behind the moon after the lunar orbit insertion burn.”

The press recognized immediately the power of the image, Earth, a brilliant oasis in a desert of darkness. The New York Times ran it on its front page above the fold. The Washington Post followed a day later. Life magazine ran a photo essay with a double-page spread of the image and lines from James Dickey, the former U.S. poet laureate.

“Earthrise,” as it would be called, went viral, or as viral as anything could in 1968, a time that saw all sorts of photographs leave their mark on the national consciousness, most of them scars: The South Vietnamese general pointing his pistol at the soldier’s head, point blank; the busboy tending to Robert F. Kennedy’s lifeless body; the civil rights activists on the motel balcony pointing in the direction of Martin Luther King Jr.’s killer.

But “Earthrise” was something different. A balm for a nation torn by the war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement, protests and assassinations.

It was perhaps this last factor that made Earthrise so iconic at the time it was released, and the reason why it has retained its status over the passage of time and stands alongside the pictures of Neil Armstrong as one of the iconic images of the 20th Century. 1968 had been a true Annus Horribilis in the United States and the world. Two iconic political figures, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, were brought down by assassins. The war in Vietnam continued. The nation was being torn apart by protests over the war and protests in largely African-American communities that devolved into widespread rioting. The Democratic National Convention in Chicago was the site of chaos and protest. And the nation experienced a contentious Presidential election that included in George Wallace a candidate who was openly appealing to racism and hatred to advance his political interests. Internationally it wasn’t much better as student-led protests erupted in nation’s such as France and the hope of a political spring in Czechoslovakia came to an end under the tracks of Soviet tanks. It was, in other words, a really bad year.

Then, we got to see this photograph. I was far too young at the time to appreciate what was happening in the world, of course, but it’s easy to understand the impact of an image like this on a nation that had been ravaged by tragedy and conflict for far too long. In one photo we saw the world for what it really is, that “pale blue dot” that Carl Sagan would later call it, and it’s easy to see how it could become a symbol of the hope that, someday, we’d be beyond the conflict and divisions that had made themselves so apparent during the preceding twelve months. We still haven’t gotten there, of course, but Earthrise and subsequent achievements in space have shown us that the grandeur of Earth and what it could be.

As we reach the 50th anniversary of Anders’ iconic photograph, perhaps it can serve that purpose again. This past year has been incredibly divisive and difficult for the United States and the world, and all signs point to more difficulties to come in the future. For one moment, though, there was a sign of what could be if we only worked for it. It also serves as a reminder that many of the problems we face today as the year nears its conclusion, such as those precipitated by the current occupant of the Oval Office, are nothing compared to what we can become.

In addition to the photograph, of course, the Apollo 8 crew was also able to communicate back home with Earth, and used the moment to help create what became a television moment that has become every bit as iconic as the photograph itself and as memorable as the day seven months later when Neil Armstrong would take ‘one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind’:

Transcript:

William Anders

“We are now approaching lunar sunrise and, for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you.

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.

And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.Jim Lovell

“And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.

And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.

And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so.

And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day.Frank Borman

“And God said, Let the waters under the heavens be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so.

And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called he Seas: and God saw that it was good.

And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas — and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

Finally, here’s a third video comparing the 1968 photograph with one taken in 2007 by a Japanese Lunar observatory:

To put the matter in perspective that photograph of Earth on December 24, 1968, includes every human being who was alive at the time except for Frank Borman, James Lovell, and William Anders.

Truly an iconic moment in human history.

And 50 years later, we still don’t get it. That small pale blue dot? That’s as good as it gets. If we take care of it, it will take care of us. If we don’t…

A quote by Carl Sagan, concerning a different picture, seems appropriate:

One of the most influential life experiences I got, was knowing that I was just an ephemeral speck in a backwater system on the outer edge of a ho-hum spiral galaxy in a dirt boring cluster.

Quite liberating, actually.

A little factoid: in one of the documentaries I saw on Apollo (probably “In the Shadow of the Moon”) they changed the mission just a few months in advance. Apollo 8 was supposed to originally be a test of the LEM in Earth’s orbit, but the CIA had found out the Soviets intended to orbit the moon like Apollo 8 soon so when we landed on it they could be like “so what, we got there first”. At the time, the Soviets had no working LEM at all.

They changed the mission and did this instead. As the astronaut in the documentary said, we had guts back then.

@Robert Prather:

Yep.

Also, the LEM wasn’t ready. It eventually flew to low Earth orbit on the Apollo IX.