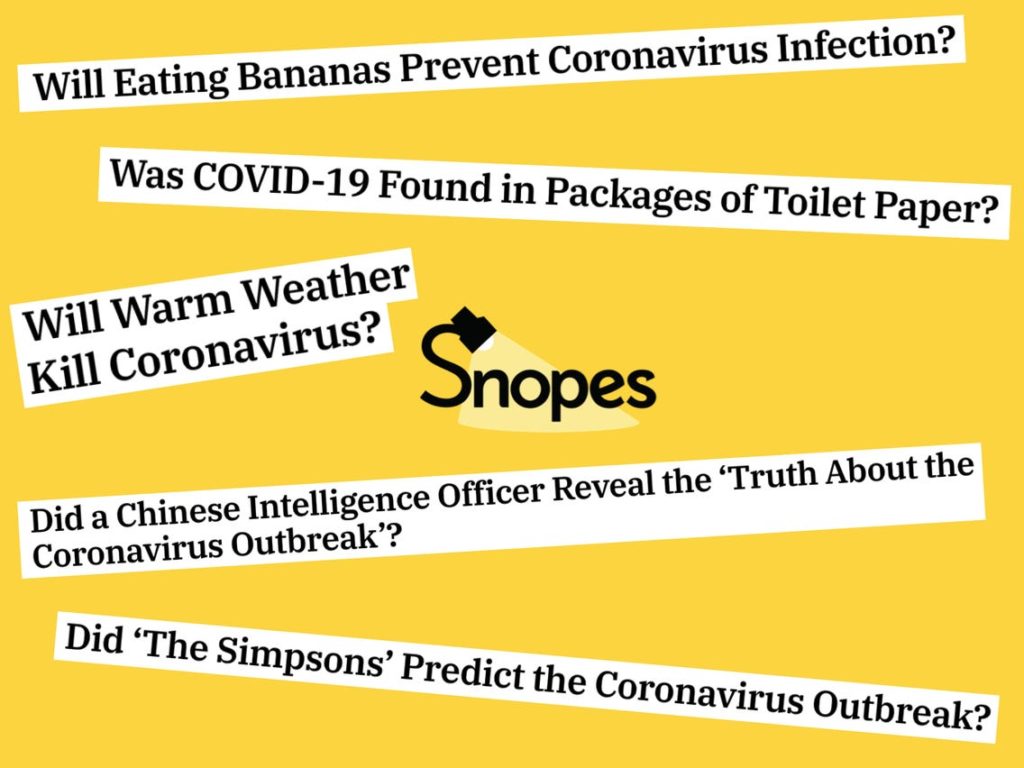

Fact-Checking in a Fact-Free World

Debunking urban legends and Internet rumors is harder than it used to be.

Clicking on a sidebar link from another story on Medium, I came across Colin Dickey‘s piece from a couple weeks ago “Snopes Debunked the World. Then the World Changed.” While much of it is familiar, it’s nonetheless depressing for those of us in the ideas industry.

The premise:

Over the past 25 years, the internet has gone from a place of possibility and promise to a dreary slog. Nowhere is this more evident than in the evolution of Snopes.com, a website that once brought a great deal of joy to the internet explorer. Since its founding in 1995 by husband and wife David and Barbara Mikkelson, Snopes’ mission of “debunking” has changed in ways both subtle and inexorable, from targeting urban legends like Bigfoot to unpacking QAnon conspiracy theories. The distinction may seem slight — both are false stories whose appeal lies in their capacity to spread and multiply — but a wide gulf separates their respective impacts. Understanding why the tools that work on urban legends fail to work on conspiracy theories is one way of understanding how our relationship to facts has changed, and it may offer some insight on how to rebuild a world of consensus instead of fear.

While I don’t know that the Internet is any more of a “dreary slog” now than it was in the days of Usenet, BBSes and AOL message boards—not to mention 2400 baud modems—Dickey’s central argument is nonetheless compelling. And, yes, I remember all of these:

Snopes came on the scene at a time when a large portion of the internet consisted of email forwards. One I remember clearly from that era was Bill Gates’ “Beta Test,” an email chain letter that circulated endlessly in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It was a simple email, supposedly from Gates, regarding an “e-mail tracing program.” “I am experimenting with this and I need your help,” the email read. “Forward this to everyone you know and if it reaches 1,000 people everyone on the list will receive $1,000 at my expense.” This email and its subsequent variations were forwarded endlessly, often with the caveat “This is probably fake, but what do I have to lose?”

[…]

Reading Snopes’ early archives offers a nostalgic trip to our earlier ignorance, a simpler time when people thought that Axl Rose had just died — or was it Steven Seagal, or Britney Spears? It debunked the original Bill Gates email chain story, along with the HIV needle story multiple times.

This sort of nonsense still abides, of course. But, as Dickey explains, it’s relatively easy to debunk.

The power of an urban legend depends in part on its vagueness, but also its specificity. Folklorist Jan Harold Brunvald, whose 1981 book The Vanishing Hitchhikerwas one of the first sustained examinations of urban legends, notes that a folk legend “acquires a good deal of its credibility and effect from the localized details inserted by individual tellers” — highway names, local landmarks, etc.

It’s this essential ingredient of urban legends that makes them susceptible to fact-checkers. Friend-of-a-friend stories lose their believability once you can Google the friend of a friend’s actual name, and they lose much of their power once you can trace how they’ve mutated and spread, placing each story alongside all of its various variants. Snopes was able to build its reputation and its following on this pretense — that diligent research could discredit even the most virulent of stories.

Reading Snopes in the era of urban legends reassured us that the world wasn’t as scary as we thought, but it did more than that. Urban legends also have the capacity to generate shame. Believing them is seductive, but as soon as one is debunked, you might feel dumb and sheepish for thinking you could ever believe it in the first place. Snopes allowed us to feel superior to those who’d been duped while covering up our own gullibility. It was the lights in the theater coming on after the horror movie—reassuring, but in a way where no one ever had to know how scared you were in the dark.

Learning not to fall for urban legends was a kind of rite of passage in the early internet. Not only was discovering the truth pleasurable, it created a community of truth-seekers. Readers of Snopes were the smart, savvy consumers of the internet, equipped to navigate it without falling for nonsense.

So, what’s different now?

These days, most of the Top 50 stories on Snopes (as of this writing) are explicitly political: rumors, lies, and fabricated screenshots concerning Joe Biden, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Kamala Harris, and Nancy Pelosi. Others are attempts to unravel the still-unfolding story of what happened on January 6, when a conspiracy theory-addled mob launched a treasonous assault on the Capitol. The site still does the work of debunking, but surfing it now is an exercise in exhaustion and dismay.

The slow evolution of Snopes’ focus began with the September 11 attacks, as the Mikkelsons found themselves increasingly responding to conspiratorial (and often anti-Semitic) rumors about who brought down the towers. By the time Barack Obama was elected, the partisan nature of such rumors was increasingly evident: Despite attempts to maintain neutrality (David Mikkelson told Wired‘s Michelle Dean that he was “essentially apolitical“), Fox News and other right-wing sources targeted Snopes as a stalking-horse for liberal bias. And as conspiracy theories surrounding Snopes continued to swirl, the site itself slowly moved from deep-fried rodents to the Deep State.

Indeed, while all of Dickey’s examples are of right-leaning hoaxes there are plenty of left-leaning ones in the top 50 list. Regardless, it’s easy enough to fact-check lies about politicians, right?

[T]he old tactic of sunlight as disinfectant fails to work on these stories. Because they reinforce one’s preexisting political beliefs, they’re resistant — if not immune — to fact-checking. As researchers have demonstrated for decades, once we’ve made up our minds about something, we rarely change it, even (in the words of psychologists Craig A. Anderson, Mark R. Lepper, and Lee Ross) “after the initial evidential basis for their beliefs has been totally refuted, people fail to make appropriate revisions in those beliefs.”

In The Enigma of Reason, Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber point out that argumentative reasoning works not by looking for evidence of one’s preexisting beliefs, but that one looks for evidence that opposing beliefs are wrong: “Reasoning does not blindly confirm any belief it bears on. Instead, reasoning systematically works to find reasons for our ideas and against ideas we oppose. It always takes our side.”

People can clearly change their minds on political matters. My friend and co-blogger Steven Taylor and I have known each other for well over two decades and we’ve both changed our minds on more issues than we can count over that time. Indeed, we’ve both been blogging since early 2003 and have changed a ton during that time. And we’re both hard-core political junkies who had a lot invested in our priors. (Conversely, we’ve both failed to turn away from our Dallas Cowboys fandom despite futility that stretches back to before our friendship.)

Still, there’s no doubt that it’s harder to change one’s mind about political beliefs—many of which are more attitudes and cultural biases than analytical conclusions—than about whether Abe Vigoda is still alive. (He was falsely declared dead way back in 1982 but was still with us in 2009. Alas, we lost him in 2016.)

And, Dickey argues, the incentives are flipped:

Conspiracy theories also invert those feelings of gullibility when one has fallen for an urban legend. With conspiracy theories, it’s the sheeple willing to take the word of public health experts and politicians who are the naive ones. Given their perpetual ironic distance from accepted fact, conspiracy theorists resist being shamed no matter how much debunking you subject them to.

As such, Snopes’ long-held formula of wry, patient debunking has increasingly fallen on deaf ears. And as authority, expertise, and facts themselves have all been called into question, the whole mechanism of debunking has lost its power. Responding to your racist cousin’s Facebook post with a Snopes.com link may be satisfying, but it’s unlikely to accomplish anything. If the act of fact-checking once helped foster a community of savvy email consumers who bonded via their superior understanding of urban legends, conspiracy theorists have instead built their own affinity groups — and those social bonds are much harder to disrupt via simple fact-checking.

Now, I have in fact managed to persuade Facebook friends that they were wrong on a particular factual claim by pointing to a Snopes link or a major media factcheck. But the real problem is that debunking a particular assertion does very little to change the worldview that made the lie seem plausible to begin with.

Whether a given celebrity is dead is pretty easy to demonstrate and, since people have little reason to hold on to the false belief, it’s easy for evidence to change minds. But if you believe the Federal government hates Blacks or gay people, it’s next to impossible to convince them that crack cocaine or the AIDS epidemic weren’t government conspiracies. The false trail just shows how clever they are! And, if you believe Nancy Pelosi, Kamala Harris, or AOC are out to destroy America, there’s no amount of individual lies that can be disproven to undermine the underling assumption.

I think part of the problem is that far too many Americans know so little about the world outside their emotional and geographical borders that they lack the instinct to say “Oh, come off it!” when they hear things that are new to them, especially on social media.

Case in point: the claim that the Pope had endorsed Trump for re-election as President. Common sense should tell anyone that the Pope would do no such thing, but Americans live in a place where evangelical religious leaders do that all the time so why not? Same kind of thing, right? What is the Pope besides Franklin Graham in a dress?

Add to that, cynical operators that encourage and perpetuate the falsehood for personal or political reasons.

As a society, we have started down a rabbit hole that leads us… Where? Likely nowhere good. This is an instance where America’s distrust of institutions, not only fails us, but exacerbates the problem.

Part of the problem is that knowledge in America exists in a vacuum. For example, the Contras did run cocaine into the US and it seems impossible that the CIA and the American government didn’t know about it.

But where the Contras responsible for the crack epidemic? Almost certainly not. And if there was an adequate knowledge base about the past, history would say the Contras needed money so they ran coke in to the US and the American government just didn’t care. That history doesn’t exist. So all it takes is one particular truth. You drop it in endless ignorance, and then presto, you create a larger conspiracy.

I think there are differences in type of misinformation, and differences in the people who receive them, and we shouldn’t confuse them and their pathologies. Snopes can work on some things but not others, and it can work for some people, but not others.

I have a sister who firmly believes that she was in a mall in central Illinois when the security came around and locked all the exit doors while they searched for a missing little girl, who was subsequently found, drugged, in a bathroom stall with her long hair cut off and dressed like a boy. This is an urban legend that Brunvald literally traced back to the dark ages. When I pointed out the incredible improbability of the story (what kind of shopping mall locks all the doors and conducts a search whenever a parent reports their kid has gotten lost? It would happen a dozen times a day! And wouldn’t something like this make local, if not national, news? She had an answer for that – the mall owners are rich and can force the police to cover up incidents that bring bad publicity.) So normally Snopes is adequate for that kind of urban legend, but for someone like my sister, it will have no effect.

As to the types of information, I suspect the vast majority of people who are QAnon friendly primarily see it as a way to disparage their political enemies and express their outrage and discuss. I don’t think it even enters the equation as to whether it is true or not. So Snopes doesn’t really have a role to play.

The really dangerous situations are the ones that combine the type of person like my sister combined with a fixation on political nonsense like QAnon.

It feels like there is a war on truth that is hurting America. I don’t know if it is mostly a homegrown return to yellow journalism, or our enemies abroad having found a way to disrupt democracy and make America weak, or what.

But, I remember a time when the crackpots weren’t encouraged. I think the turning point was the death of Vince Foster — a conspiracy theory that popped up on the right and then got into the mainstream news with a weird both-sider-ism. The internet has made it worse.

There were conspiracy theories before then, such as the fake moon landing and lizard people, but those were for loons.

Maybe the JFK assassination? But I don’t recall any specific theory of who did it taking on a life of its own, so much as a disbelief of the official version (which depends on a magic bullet, so it’s not like skepticism is crazy)

Reason is one operating system, Faith is a different operating system.

Your brain is a computer. It stores data. But it’s more than a computer in that it assesses and ranks and prioritizes data. It’s that judgment function that has failed in so many people. (74 million, give or take.). The internet – following on earlier advances in data transmission, such as radio and TV – increased the amount of data to be analyzed. At the same time the gatekeepers were pushed aside or simply overwhelmed, so that the quality of data reaching people’s brains deteriorated, on average, even as the volume of data increased exponentially.

IOW: larger quantities of bullshit were being pumped into more brains. It’s a bit like a drug: at low concentrations LSD may open your mind. At high concentrations it may scramble your mind. The data flow went from some percentage of bullshit to a much, much higher concentration of bullshit.

Some people can be their own gatekeepers, most people either can’t, or can’t be bothered. The people who can, tend to be more intelligent and/or educated; the people who can’t tend to be less educated, less intelligent, and what critical faculty they ever possessed has been systematically subverted by religion’s insistence on their Faith OS as a valid tool for processing data, a valid alternative to the Reason OS. Of course that’s nonsense – faith is the opposite of analysis.

The Reason OS requires a lot of computing power, the Faith OS can run on your smart refrigerator’s processor. So faith is more likely to be the OS running in less capable brains. It is more difficult (but not impossible) to hack the Reason OS, but the Faith OS has effectively no security, no defenses at all. People running the Faith OS can be easily programmed by anyone claiming to adhere to that same faith. It’s as if all their PIN’s were the same: J-E-S-U-S. Type that in and their little brains open like flowers thirsty for rain.

Genuine gatekeepers devoted to reason and truth are pushed aside and bogus gatekeepers are able to easily exploit the unprotected brains of people running the Faith OS. Two completely different operating systems produce two completely different versions of reality. This is where we get the two versions of reality that forms the substructure of our politics.

The mind is shaped by DNA, environment, free will and random chance. All things uniquely human start there, in the individual human mind. That’s where the battle is. Take the Faith OS off the market, so to speak, leave no alternative to the Reason OS, and guess what? The toxicity is drained from our politics. People will still disagree, perhaps sharply disagree, but we’d be operating in a single reality.

But, I remember a time when the crackpots weren’t encouraged. I think the turning point was the death of Vince Foster — a conspiracy theory that popped up on the right and then got into the mainstream news with a weird both-sider-ism. The internet has made it worse.

To me, the most telling thing about the Clinton conspiracies was that they all were rooted in the Reagan-era 80s. Not only the S&L stuff (which never made any sense, considering McDougal ripped the Clintons off, so what was their take in the scam?) but the connection with Mena and the CIA running in drugs. The villain behind it wasn’t Ronald Reagan or George Bush or any Republican in DC but the governor of Arkansas and his wife. And that’s why Vince Foster was killed, because the Clintons ran the CIA in the 80s.

I do think a lot of right-wing conspiracies are desperate evasions of actual truths. It’s not the lizard people, Jewish bankers, or pizza chains, but just normal upstanding white people who are doing all of what the conspiracies are said to be doing.

Out of a badly misplaced sense of curiosity I checked out the current top 50 at Snopes. I’d score 26 as political, so over half, but barely. I score 12 of those as Left leaning and 14 as Right. Counting mostly true/false as true/false and satire as false, I make the 12 Left leaning as 7 T, 3 F, and 2 unclear or mixed. The 14 Right leaning run 3 T, 10 F, and 1 unclear or mixed. This is, of course, completely unscientific. And a lot of it is gray area. I scored ‘Did Limbaugh say these racist things’ (mostly true) as Left leaning, but ‘Did Limbaugh smoke’ (true) as apolitical. YMMV.

One thing that’s occurred to me is that there are two countervailing aspects to misinformation in the Internet age. On the one hand, there’s more critical and debunking information in the immediate vicinity through which you can evaluate the the veracity of claims you hear. On the other hand, there’s also a lot more misinformation in the immediate vicinity.

Over the years I have often focused more on the first aspect and therefore maintained a relatively optimistic outlook about the Internet. But it’s largely because I’m thinking of it on a personal, individual level: the Internet has made me better informed and better able to tell truth from falsehood. Not only do I no longer believe in urban legends I used to accept, I’ve developed a better sense for these things: I often suspect something’s an urban legend before I even check it out. Some of that’s simply due to growing older and more mature (I was in my late teens at the start of the Internet revolution of the mid-1990s), but sites like Snopes helped me hone that skeptical antenna.

The trouble is that on the macro scale, it’s the second aspect that’s winning out. People have retreated to their little bubbles and it’s made them not only more receptive to misinformation, but more insulated against mainstream sources of information, which, while imperfect, used to provide more of an anchor against people descending into their little worlds like this. By no means did this problem start with the Internet, but the Internet has greatly increased it.

Michael, you just love to rail against religion and I am not going to stop you from being you. It took me all of less than 15 seconds to type in a query into Google about Pope John Paul II and science and receive a whole ton of articles that quote the Pope as being hip with science and religion co-existing and at times crossing the streams.

Quote from Pope John Paul II:

“Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.”

The above is a wonderful quote and I have no doubt you were aware of its existence before I pasted it into my comment.

I’m sure I’ve seen Snopes called “fake news” or liberal media or somesuch, and therefore easily dismissed. That’s another facet of this: only trust sources that we tell you to trust.

But I know this grapevine. I always appreciated how effectively this movie scene highlights the fallibility of human transfer of information (parrots are clearly much more effective).

@reid:

These are the kind of people who get their “news” from The Gateway Pundit and The Conservative Treehouse.

@CSK: I suspect you’re right.

@Modulo Myself:

It’s disappointing how it always seems to be anti-semitism. I’m convinced the lizard people celebrate Chanukah, and the death of Jesus, and bathe in the blood of Christian newborns.

@Not the IT Dept.:

Not a problem exclusive to Americans.

I’d also add a lack of knowledge of science and technology. No one who understands basic biology and keeps up even a little with developments in genetic engineering, for instance, would believe for a minute that HIV was designed in a lab (in the effing 1980s!)

Or take the current COVID-19 pandemic. Many, many diseases are known to be transmitted from animals to humans, and many of these caused pandemics. The Black Death, for instance, came from infected rats and fleas. Malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes. H1N1 came from farm pigs. It’s a long list. So to find out SARS-CoV-2 comes from bats or pangolins is no surprise.

The difference between a zoonotic disease and an epidemic or pandemic one, is whether sick humans can transmit the pathogen to one another. For instance, a person who contracts rabies is not likely to pass it along to other people. Someone who contracts avian flu is.

@Michael Reynolds:

We are a much less religious country than we used to be. And insane conspiracy theories are rising to the halls of Congress, and into the close advisors of the last president*.

Maybe the problem is that mankind is not reason-based, at least not for long stretches, and the decline of religion leaves a void. Maybe religion is the less-worse, free-needles, harm-reduction approach to humans in large groups.

Religion can definitely be hijacked, but “love thy neighbor, Jesus loves you, this lamp’s fuel efficiency is a miracle, the eight-fold path will lead to enlightenment” is way better than a global conspiracy of pedophiles at the highest levels of society.

——

*: When, precisely, did Micheal Flynn think that Donald Trump was fighting an international globalist pedophile ring? Like, where was it on his calendar, and what was he doing about it? And, just as importantly, did he think Trump was fighting it from the inside?

@Kathy:

A lot of non-US people I’ve interacted with know an awful lot about what is happening in the States, and I frequently know a lot less about their country, so for the most part I take their complaints about American ignorance in stride. But every once in a while someone gets a bit obnoxious about it, claiming that, say, the French or the English are so much better educated than Americans and our ignorance of their country is proof. A few times I’ve challenged them: let’s pick a country, non-European, neither of us is from and see who knows more about it. I haven’t been taken up on that.

@MarkedMan:

The goings on in America are important to most of the rest of the world. There’s an aphorism, “When the US sneezes, mexico gets pneumonia.” this applies to other countries.

So finding a Mexican national well informed about America is common. Finding one more than minimally informed about Guatemala or Uruguay, is rare.

@Gustopher: Are we a less religious country, or are we a less professing country? And is that decrease in profession indicative of a loss of faith, or an indication that societal norms are evolving (re-evolving?) to the point where far fewer individuals feel a need to profess faith out of fear of societal (and too often physical) retribution?

There are still large parts of the world where a public profession of athiest or agnostic belief (or my favorite, blasphemy) can result in physical harm, imprisonment through state tribunal, and death.

@Kathy: In Korea, it went

(Clearly, China is much less powerful, only causing worry about a cold. 😉 )

@Owen: indeed, the guy who invented the Darwin fish for your bumper says he always carries a couple extra ones around in his car because of how often he sees ones that have been vandalized.

@Owen: All the surveys show fewer and fewer people identifying with any religion, so I would say that the best data I know about is that we are a less religious country.

But I don’t think we are a more rational country.

Religion has been with humanity for the last few thousand years — pretty much as soon as there is writing, there is direct evidence of religion, and there is always indirect evidence before that (but you run into questions like “is that an altar, or just a cool public sculpture?”)

I’d love to take some infants and desert them on an isolated island to be raised by wolves, just to see if they would develop a religion in a few generations, but not only would that be unethical, I would probably be dead before we got good data.

All of this is to say that religion may be the default state of mankind. Certainly every culture we have found has a significant religious component to their life, but that could be contamination from other cultures. None of the isolated groups we found during the age of exploration, conquest and colonization were atheists, to the best of my knowledge.

Our friend Micheal Reynolds’ regular rants about religion might be the equivalent of ranting about glaciers, gravity or geometry.

Even the most rational people take so much as a matter of faith that it’s laughable — from the existence of New Zealand, to cause-and-effect, to the idea of free will. We simply don’t have time to evaluate and test everything, so we rely on trusted sources to cut it down to something reasonable.

And then we get a cat because we think it will love us, and we convince ourselves that it does despite all evidence to the contrary.

These are some interesting perspectives on human neuroscience, psychology, and decision-making. And expressed with such confidence. I’ve enjoyed reading them.

@Gustopher: I am supposing what we define as religion differs (and likely love as well). I’m sorry your cat doesn’t love you, the several cats I have shared homes with have been loving.

@Owen: My cats have many instinctual behaviors that I interpret as love.

For instance, they greet me at the door. They are always on my bed in the morning, to remind me to feed them. The follow me from floor to floor, in case I go near the laser pointer, or one of the other toys.

Earlier today, right after I had done my INR finger-stick test, my cuddliest cat began purring like mad and hopped into my lap, and kept trying to lick the droplet of blood from my finger. I expect that if I die she will start eating me in about half an hour. She’s super cute and friendly.

The other cat is standoffish and skittish, but will often do something that I interpret as sweet (a gentle head butt, perhaps) and my heart melts.

@Gustopher:

To play the Devil’s Advocate, @Micheal said “FaithOS” not “ReligionOS”. I mean, we know he means religion but his point isn’t all that wrong.

They are not the same thing – religion is codified faith but faith as a concept can exist without religion. It’s a very American thing to automatically inflate the two notions because we are so used to the pervasiveness of religion. Faith in this context can be anti-vax beliefs that have no basis in reality but serve a very real purpose for people struggling to understand why their child isn’t neuro-typical and attempting to assign blame. Faith and reason can co-exist but they have different requirements for existence that often cause one to choose between two competing realties. Faith requires conviction while reason requires evidence; I don’t have to believe a fact for it to be true but I do need to accept a notion for faith to function. Thus faith is more fluid with regard to data input quality and complements the human tendency towards confirmation bias. Faith tends to give us comfort, value and reinforcement whereas reason tends to remind us we are lonely, insignificant specks on a has-been planet orbited by a cold, indifferent sun. Viewing the world through FaithOS gives meaning to random, meaningless actions and offers reassurance there’s a plan in the chaos of existence. In other words, one’s the user-friendly but highly bug-ridden common choice where the other is the more expensive and resource-intensive to maintain but grants the best user experience and ROI.

Actually I think the Internet is a great place. Not sure how to wire a three-way switch? Five minutes on the Net will find you someone who show you how. Not sure what metric tensor is? A quick search will point you at a detailed Wikipedia article. Not sure what are the currently accepted crustal plates? A quick search will give you an excellent start on understanding plate tectonics. Need to know how to write a quick Python game? In a minute you can find several hundred examples, some explained very well. Want to learn how to play say “Blueberry Hill” on the piano? There are several on-line tutorials to choose between.

Anyone who reached adulthood before the Net was established remembers how difficult (and/or) time consuming it was to find up-to-date sources in libraries (or sometimes even out-of-date sources).

There’s a lot of junk on the Net, but its easy to ignore, a small annoyance compared to the wealth of teaching that’s offered (much of it free) on the Net. You’re not using it correctly if you find it a dreary slog.

People want to believe in what they read, and rely on headlines rather than the actual story. The dearth of information available online is great, but some people will not accept that the headline they saw could actually be some slanted piece of clickbait. No need to drag the modern day press into this, they’re the biggest beneficiaries.

I totally fell for the Spike Jonze died prank.

It came from VICE official accounts which was then airing a Jonze’s shot series which I enjoyed a lot.

I was bummed. I like him a lot. Mostly as a director, but he has a weird, off-beat charm as an actor as well in Three Kings and The Wolf Of Wall Street.

I was super fucking pissed when I found I had been deliberately pranked.

It took me two months to realize it was a sophomoric prank. Uncool!