Mob Rule or Representative Democracy?

David Broder argues that, despite “out of touch politicians” being crowd pleasing fodder for stump speeches, modern communications have actually made decision makers too responsive to a poorly informed, emotional public’s will.

From Aristotle to Edmund Burke, philosophers have written of the healthy tension that normally exists between the understanding and strategies of leaders and the sentiments and opinions of their people.

In today’s Washington, a badly weakened president and a dangerously compliant congressional leadership are no match for the power of public opinion — magnified and sometimes exaggerated by modern communications and interest group pressure.

[…]

The point is pretty basic. Politicians are wise to heed what people want. But they also have an obligation to weigh for themselves what the country needs. In today’s Washington, the “wants” of people count far more heavily than the nation’s needs.

You can win elections by promising people what they want. But you win your place in history by doing what the country needs done.

This column was written in response to the failure of Congress to pass the immigration reform bill and to renew fast track authority for trade negotiations but it’s a familiar lament. Politicians should be strong and stand up for the national interest regardless of the short term political consequences. That’s Statesmanship.

Yet, as Bernhard points out, what the “national interest” might be on a given issue is merely a matter of opinion. Why is David Broder’s opinion more valuable that that of the masses who organize and call their representatives to express their concerns? And I say that as someone who agrees with Broder on both of the issues in question.

And, amidst a decidedly un-Broderesque tone, BooMan has a point:

Just because THE PEOPLE have a majority opinion on some issue doesn’t make them right. That is why we have all these protections for minority opinions. But you have to be a blithering idiot to be able to look at the current landscape in America and think it is THE PEOPLE that are out of touch right now and not the denizens of the Beltway.

[…]

It is the Beltway types that don’t want to face up to consequences of their profound failures. THE PEOPLE can see the budget numbers, the casualty reports, the failed government services, and the official corruption.

The Progressive Era journalist Walter Lippmann, who invented the modern study of public opinion, was skeptical of governance by the masses. Daniel Schugurensky provides an excellent synopsis of the debate:

For instance, he argued that participatory democracy was unworkable, that the democratic public was a myth, and hence that governance should be delegated exclusively to political representatives and their expert advisors. Based on empirical evidence about the efficacy of political propaganda and mass advertisement to shape people’s ways of thinking, Lippmann contended that public opinion was highly shaped by leaders. Lippmann called this process of manipulation of consciousness ‘the manufacture of consent’, a concept that Noam Chomsky would popularize many years later in his writings. Lippmann argued, first in ‘Public Opinion’ and later in ‘The Phantom Public’, that since ordinary citizens had no sense of objective reality, and since their ideas are merely stereotypes manipulated at will by people at the top, deliberative democracy was an unworkable dogma or impossible dream. In his view, the most feasible alternative to such democracy consisted of a technocracy in which government leaders are guided by experts whose objectives and disinterested knowledge go beyond the narrow views and the parochial self-interests of the average citizens organized in local communities. Lippmann saw advocates of participatory democracy as romantic and nostalgic individuals who idealized the role of the ignorant masses to address public affairs and proposed an unrealistic model for the emerging mass society. He opposed such a model with his own model of ‘democratic realism’ based on political representation and technical expertise.

John Dewey, in his response to Lippmann, first in a review published in The New Republic (1922), and later in his book The Public and its Problems (1927), contended that democracy should not be confined to the enlightenment of administrators or to insiders like industrial leaders, and highlighted the importance of public deliberation in political decision-making. However, he was not an advocate of any type of deliberation. He contended that just letting discussion go, without eliciting facts of any kind, and without appealing to common meanings, was fruitless (Hart 1993). While Dewey did not dispute Lippmann’s claim that social inquiry and policy design can be done by experts, he claimed that all the relevant facts and potential implications of such inquiry and proposed policies should remain a public trust which must not be manipulable by private interests. In The Public and its Problems (p. 365), he admitted that “it is not necessary that the many should have the knowledge and skill to carry on the needed investigations; what is required is that they have the ability to judge of the bearing of the knowledge supplied by others upon common concerns.” For Dewey, once the relevant facts are made public (and in this regards he placed great emphasis on the need of a truly free press), the role of discussion is to determine the exact nature of the common good in that particular situation. Dewey recognized that intervention by the public is not possible without a better organized and educated public, but argued that lack of education, stupidity, and intolerance lead to bad governance not only in democracies, but in monarchies and oligarchies as well. Thus, argues Dewey, the democratic system is not responsible for the poor decisions of the public in local policy-making, such as the prohibition of the teaching of evolution in schools (which Lippmann cited as evidence of the inability of the public to govern). For Dewey, the weaknesses of democracy are symptoms, rather than causes, of the problems of modern society.

While Lippman got it right in terms of the manipulability and thin understanding that the general public has on most issues, Dewey’s conclusions are nonetheless right. It’s undisputable that bureaucrats, White House and Congressional committee staffs, think tankers, and even politicians have more knowledge of the issues than the masses. That’s the nature of professionalism and expertise. It does not, however, follow that those with the most knowledge ought get to decide.

For one thing, the experts seldom agree on complex issues. Indeed, the elite debate on such things as immigration and trade policy at the expert level is remarkably similar to that among non-elites. Sure, the former have more data at their fingertips and can debate the issues more fluidly. But at the end of the day, these issues don’t come down to scientific calculations but priorities, ideologies, and personal experiences.

Experts should not consult public opinion on technical details of carrying out policy. John Q. Public has no earthly idea how many troops we need in Iraq, how to go about allocating scarce Homeland Security dollars, or how many engineers from Pakistan the economy can absorb.

At the same time, there is a wisdom of the crowds at the big picture level. The public judgment on whether continuing a war is worthwhile, whether millions of people from another country should be flooding across the border in violation of our law, or whether we should spend millions on bridges to nowhere should be taken into account. To be sure, they might get it wrong from time to time. Then again, so do the experts.

Thanks for raising this. Your timing could have been better, though, as Independence Day was yesterday!

This is an issue that has been on my mind throughout my career. I was being paid to represent America, Americans, American cultures and values. There were plenty of times when what I was representing did not match up well with reality, at least external reality. There were times when I questioned whether it was worth putting my and my family’s lives on the line to promote really stupid and counterproductive policies.

Nevertheless, US policies are decided by a legitimate process that approximates the ‘will of the people’, rightly or wrongly, most of the time.

The American people will rarely be interested in the details of any given policy. They will be interested, correctly, in how it affects them and how it affects their views of the world, present and future.

It is morally incumbent on the experts (who are necessary, I believe) to explain why a particular policy is better than its alternatives. That involves work. More importantly, it involves transparency. Work and transparency are not necessary concomitants to efficiency, however.

Some things simply cannot be fast-tracked, cannot be done expediently. A lot of wool can be pulled over the eyes of the average voter on a lot of issues. But some issues are so important to the individual voter that s/he will simply dig in his/her heels if someone tries to ‘railroad’ a solution that does not address the specific concerns and fears being felt.

There is a danger of important issues being spun by government. The danger is even higher, though, when government is the least audible voice, drowned out by competing experts with unknown agendas. It’s not just this Administration that has a poor record of clear communication. That’s the record of most city, county, and state governments and of Administrations since the birth of the Information Age.

I recognize, too, the danger of government propagandizing its citizenry. But there is an equal danger presented when government cannot express itself clearly and transparently to that citizenry.

Oh, our poor elites, having to listen to the unwashed masses express themselves as if what they had to say really mattered.

How dare we? How dare we speak of matters we have no right to speak upon? How dare we talk in ways not sanctioned by the proper authorities? Why, you’d think this was a democratic society or something. And they, our long suffering betters, forced to merely bitch and moan.

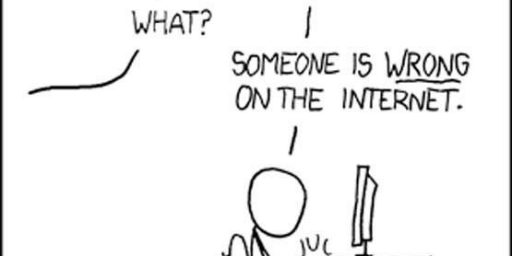

What shall they do? They who are facing a world given voice, where unsanctioned blithering idiots have recourse to means of communication the sanctioned blithering idiots didn’t need to get their message across. How will they deal with people exposing their errors, correcting their claims, and writng snarky comments with third rate sarcasm on blogs such as Outside the Beltway?

All I can say to them is, let the door hit your ass on the way out. I want to hear you yelp.

So when were our great and wonderful leaders exampling their superior knowledge of the “immigration reform bill” and it’s necessity anyway ? Was it when Lindsay Grahamnesty was promising to “shut the biggots up”? Or was it when Linda Chavez was comparing the opposition to eugenics loving nazis ? Or was it when they avoided every opportunity to have a substantive debate on the issue ?

Frustration with the people getting their way via the kneejerk reaction to sensationalized “news” stories is one thing, but this was a situation where incredible odds were overcome as the truth actually won out over an onslaught of 2 branches of the gov. AND the 4th estates wishes. That is the essence of America. The underdog won. The elites took it in the shorts. Sorry, I just can’t help but cheer that one.

While I can accept conservative supporters of the bill have a different view to mine, I was somewhat surprised at how quickly they started the name calling. There was an immediate level of, cut-to-the -chase, viciousness has lessened my opinion of them.

What follows from this is that the professionals need to do a much, much better job than they do right now in conveying the benefit of their expertise to the electorate.

Essentially, I echo John’s sentiments above in this. There is something that it requires beyond work and transparency, however. It requires that the professionals believe that it is their job to communicate their conclusions and the basis for their conclusions to the voters.

Human government is more or less perfect as it approaches nearer or diverges farther from the imitation of this perfect plan of divine and moral government.

Dave: I agree. I’d taken what you pointed out as a ‘given’, though of course that’s not always the case. Or even mostly the case.

I’m happy that we have people like Alan to stand up for the Robespierre sentiment. But as that particular experiment proved, leaving things to the masses doesn’t always work out to everyone’s benefit.

If one thinks that mob rule is only a historic oddity, I suggest taking a closer look at countries like India. World’s largest democracy (TM) can still devolve into rioting and bloodshed at the least provocation, if it hits a popular nerve. For that matter, we can look at how our own democratically elected school boards go about banning books, stopping sex education, insisting on non-science in biology books.

I don’t condemn those people as moral failures, just as pretty dim bulbs. But it’s a fact that those bulbs’ votes count just as much as mine.

Why stop at India ? What about the thugs who tore down the great wall of the proliteriat that separated East Berlin from the hoardes of uninformed,freedom loving capitalists on the other side ?

I am reminded of the “war of experts” in court cases, where the defense presents its eminent flacks, followed by the prosecution presenting its opposing team of flacks on the issue at hand.

It leaves a jury of peers to arrive at the result by judging the truth value of the various expert opinions and the presentations of the lawyers.

The point being that one can find experts to champion just about any position one might want to promote. So is it with congress, their experts on the Left and Right, the administration with their own experts (or whomever they listen to) and the 12 ordinary people who ultimately must judge guilty or not guilty.

The marvelous thing is, it does work remarkably well most of the time, especially if the facts are presented adequately (transparently?)and the lawyer or expert rhetoric (manipulations?)is filtered by common sense.

It is slow, however,as justice tends to be, which is another problem entirely. So we must wait a while for the next presentation.

Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates,every Athenian Assembly would still have been a mob.

Great post JJ – I would complain about it not being on the 4th, but that’s Broder’s fault, not yours.

Congratulations, James. You have boiled down to its essence the fundamental difference between a democracy (Athens) and a republic (the USA).

What Broder seems to miss is the proposition that even in a republic, representatives answer to the people. That is why as a matter of practical politics in the USA, it is generally unwise to get too far ahead of public opinion. Otherwise, you will find yourself voting for or against your successors rather than running against them.