No Previously Published Works Will Enter Into US Public Domain Between Now and 2019

No previously published works have entered the US Public Domain since 1978. And none are scheduled to enter until 1923. So what are we missing?

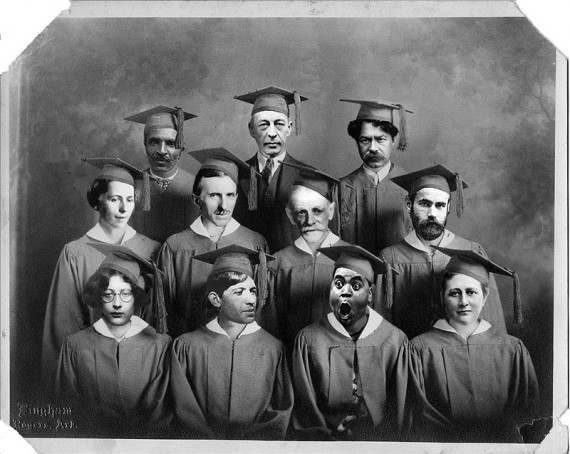

Middle Row (left to right): Sophie Taeuber-Arp; Nikola Tesla; Kostis Palamas; Max Wertheimer

Bottom Row (left to right): Simone Weil; Chaim Soutine; Fats Waller; Beatrix Potter

[Artwork and caption from http://publicdomainreview.org]

With the turn of each new year, depending on where you live, a number of previously copyrighted works (including literature, music, and film) enter the public domain. They pass from being the property of the authors, or companies that the authors were working for, to being owned by the public writ large. Once public domain, these works can legally be reproduced, remixed and redistributed by any and all people (within the borders of a given country).

Since, internationally, the most common copyright term is “life plus 70 years” (e.g. most European Union members, Brazil, Israel, Nigeria, Russia, Turkey, etc.), the public domain “Class of 2014” is filled with individuals who died in 1943, including such luminaries as George Washington Carver(inventor and author), Sergei Rachmaninoff (composer and musician), Nikola Tesla (scientist), Fats Waller (musician), and Beatrix Potter (author). Countries whose copyright term is “life plus 50 years” (including Canada, many countries in Africa, the Caribbean and Asia) will add the likes of Robert Frost, Sylvia Plath, William Carlos Williams, C. S. Lewis, and Aldous Huxley to their public domain.

So who gets added here in the US? Nobody. Nada. None. In fact, even though the US is “life plus 70 years,” no works will migrate to US public domain until 2019.

This article from the Economist’s Babbage blog explains why:

In 1978 and 1998 [The US] Congress extended, reshaped and expanded copyright durations and the scope of copyright for existing and future works (see Peter Hirtle’s authoritative website for the gory details). For new works produced after January 1st 1978, the period of protection is the same as in the EU. But for works published from 1923 to 1977 for which copyright was properly registered and renewed (as applicable in the period when originally registered or created), copyright was prolonged to a full 75 years from publication regardless of the author’s presence among the living. (Work by employees for a company or for which copyright has been entirely assigned to a firm, so-called “work for hire”, has a different set of rules.)

[Then, in 1998, through the unanimously approved Sonny Bono Act of 1998, Congress extended copyright on works from that 1923-77 period to 95 years.]

The net result is that works published in 1923 will only begin to enter US public domain in 2019. Then, in 2020, all works published in 1924 will enter the US public domain. And so on.

Until then, not a single, previously published work, will enter the Us public domain.

Why should we care that the US is lagging woefully behind in terms of the expansion of public domain works? Writing at the Huffington Post, Jennifer Jenkins, Director, of the Center for the Study of Public Domain at Duke Law School, makes the following arguments:

It matters for price. As studies have shown, not only are public domain books cheaper, they are available in more editions and in more formats. (Importantly, there is another benefit: when books are in the public domain, anyone can make Braille or audio versions for visually impaired readers. No permission required. And if you think no one would object to such uses, sadly you would be wrong.)

It matters for creativity and free speech. The public domain feeds creativity. Authors build on the cultural artifacts around them. The Waste Land is anything but: it’s a fertile bed of references to dozens of earlier works (from Homer, Virgil, Shakespeare, Kyd, Chaucer, and Milton, to name a few). Michael Chabon — one of my favorite authors — describes how his novel Summerland builds on public domain sources such as American folktales, and stories from Greek, Norse, and American Indian mythology. Some claim that Lolita was borrowed from an earlier story of the same name; pointing in the other direction, Nabokov’s heirs sued the publishers of Lo’s Diary (a retelling of Lolita from the girl’s perspective) for copyright infringement. Examples could (and do) fill volumes. In a brilliant article on the subject, author Jonathan Lethem calls it “the ecstasy of influence.”

What happens if these underlying sources are copyrighted? As Judge Richard Posner pointed out, “Romeo and Juliet itself would have infringed Arthur Brooke’s The Tragicall Historye of Romeo and Juliet… which in turn would have infringed several earlier Romeo and Juliets, all of which probably would have infringed Ovid’s story of Pyramus and Thisbe.” You get the point — without a rich public domain, much of literature would be illegal.

[MB: It should be noted that the Walt Disney Company, one of the most fierce advocates for the continued extension of copyright, has made much of its fortune creating feature length animated versions of public domain stories]

[…]

It matters for access. Here is the real tragedy. In many cases, despite all of these extensions, no one is benefiting. The expansive copyright term may be great for a few works making money years later. But the vast majority of books exhaust their commercial potential relatively quickly — when the copyright term came in renewable terms of 28 years, copyrights for 93% of books were not renewed. A Congressional Research Service study found that only 2% of works between 55 and 75 years old continue to retain commercial value. For the other 98% of works, there is no benefit at all from continued copyright protection. But the public — at least those members of the public that don’t live in the Library of Congress’ stacks — loses the possibility of meaningful access. In fact, in many cases the copyright holder cannot even be found. For these so-called “orphan works,” the effect of term extension is truly ironic. Copyright, intended to promote access to creativity, ends up, in Justice Breyer’s words, condemning books to “a kind of intellectual purgatory from which [they] will not easily emerge.”

In terms of the “Class of 2014”, current US copyright law means that Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit stories are public domain, because they were published prior to 1923, while many of Rachmaninoff’s recording and compositions will remain under copyright for some time because they were published after 1923. In fact, his later works will not be completely public in the US until 2026 — eleven years after they entered the public domain in the rest of the life+70 countries.

And that is provided the law stays the same. It’s entirely possible that as 2019 approaches, Congress could once again vote to further expand the copyright period. And, without a doubt, there are a number of media companies, including the aforementioned Walt Disney, that support such action.

What remains to be seen is if we as a nation, will come to our senses on this issue and get back in step with the rest of the world. Especially since we are rapidly approaching a point where the international disparities of what is *and* isn’t available in a given public domain are going to become increasingly apparent, especially given the nature of electronic media.

For more on this topic, including things that, under previous US Law, would have been in the commons today, I suggest visiting Duke’s Center for the Study of Public Domain.

—

Note: While works are not migrating into Public Domain in the US, the Public Domain is still growing. Today’s creators can choose to release their work using so-called Copyleft systems, which provide varying degrees of public rights. The best known of these is Creative Commons.

IMO, copyright should be for 70 years or the author’s life, whichever is longer. I find it ridiculous that Asimov’s “Nightfall” , Heinlien’s ” If This Goes On-” and John W CAmpbell’s ” Who Goes There?” aren’t in the public domain.

I would make copyright 15 years.

@stonetools: I wouldn’t have it even that long. Bring back to the two 28-year terms, and add shorter periods (once every 7 years?) that you need to pay annuities. If you don’t care enough about your copyright to pay the annuities on it, then you don’t get to keep it.

@stonetools:

Interestingly, these works actually present the downside to Life+70 as each of them were early career works by these authors. So, under current US law, they will enter the public domain before they do in other +70 countries.

If This Goes On (1940)

In US (Publication date + 95) = 2036

In +70 (Author’s death + 70) = 2059

Who Goes There? (1938)

In US = 2034

In 70+ = 2042

Nightfall (1941 – Short story)

In US = 2037

In 70+ = 2063

These serve as a good example of the limits of Life+70.

@grumpy realist:

What you said … agree completely.

What we have now is absurd, and it is astray from the original intent of copywrite laws.

Thanks Congress!

As one of the few (maybe only) people here who makes 100% of his income via copyright, I have no objection to reducing the length, or for requiring renewal after an initial reasonable period of time.

I have never raised an objection to things that might arguably conflict with my copyrights, such as fan fiction and fan videos. Nor would I ever quibble over reasonable quotations. I also don’t generally get upset over the torrents.

Where I draw the line is at major corporations — Hollywood, obviously — using something of mine without my permission.

I’ve had some experience now dealing with Hollywood, as has my wife. The book author has an important role in the creative process. Specifically, we can often choose among more than one potential producer. We can try to find the producer we think will do the best job of it. Were we deprived of that role, the rights could be exploited by whoever, and the value of the property would plummet. Not just in terms of what we earn – which ain’t as much as people think – but in terms of the quality of the final product.

So copyright remains vital, but no objection to making it less of a pain in the ass.

The greatest insanity of all in intellectual property law is retroactive extension of copyrights. Even if you accept long copyright terms, the idea that being able to extend the copyright of something past the date at which they would have expired under the law as it stood when the work was created does anything other than to preserve the bottom lines of big companies is unfathomable to me.

@michael reynolds:

Without a doubt, copyright is critical — especially for the protection of content creators. And you lay out exactly why its important.

Whats important to stress — and I realize that you are not making this argument – is that agitating for copyright reform *is not the same* as trying to abolish copyright.

One of the common tricks of larger entities in the content/media industries (again I am not accusing you of doing this) is to represent relatively conservative proponents for copyright reform, such a Lawrence Lessig, as being people who will stop at nothing to tear down copyright and make everything free.

One the one hand, it is a great shame, on the other I am finding a lot to read on my phone written 1905-1915. The most recent a book on firearms with digressions on the (then current) war in Europe.

@Dave Schuler: Yes, the purpose of copyright is to encourage the creator to make something they might not have. Since the work was published without the incentive, its retroactive application could not have encouraged the behavior. Congress just gave a gift to those who favored.

Monteiro Lobato will enter public domain in 2018. He is the Brazilian writer that in 1926 wrote a book about a Black President of the United States.

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/foreigners/2008/09/the_black_president.html

He is famous in his home country as a writer of children´s books(And yes, his children´s books are pretty interesting, relatively long stories with references to both European literature and local folklore).

That´s going to be interesting, and I bet that we are going to see translations of his work.

@michael reynolds:

The majority of my income was in software, the majority of which was copyrighted.

My dabbling in open source might be like be like the unpaid content you offer us all here. Not everything is a paid gig.

@john personna:

Very true. I’ve noticed how much better my spelling and punctuation are when I’m getting paid.

@Matt Bernius:

I understand the desire of some to eliminate copyright – it would be convenient, aside from the fact that 90% of what’s written would never be written to begin with. So not all that convenient in the end.

And I understand the idea some writers have that their work should benefit their children and grandchildren in perpetuity. But I think we need something short of young William Shakespeare XVII cashing royalty checks for Hamlet.

Balance, as always.

@michael reynolds: I think JP has revealed one of Hollywood’s not-so-secret slogans: “Not everything is a paid gig.” The writer should be happy for the exposure and publicity. Harlan Ellison has a humorous rant about this that’s been uploaded to YouTube.

@Matt Bernius:

But you see so much of this in everything these days. Propose some modest gun control regulations and all of a sudden you’re advocating for the removal of all guns by the government. Ask for women to have the right to choose during the first trimester and pretty soon they’ve got us ripping out babies a day before birth and tearing them to pieces. Support gay marriage and soon you’ll hear that you really support people marrying animals. I honestly don’t know how we ever managed to get anything done in this country. I would think that if automobiles were invented today, we’d be riding around without licenses, registrations or insurance because Big Government!!!

@Dave Schuler & @PD Shaw:

Elsewhere in her Huf Post article, Jennifer Jenkins touches on the unintended consequences of retroactively applied copyright extensions and how, in at least one case, they threatened a new, creative, derivative work:

@michael reynolds: I don’t think the writer has to plan for his/ her heirs to take control of the literary corpus after his death, they just do it after his death if they so choose.

I have some reservations about the extent to which the wishes of the heirs should be considered to be the wishes of the decedent. What if the writer did not want some of the remaining works published? Did the writer want his heirs to sell the rights to his characters to a line of strip clubs? And most important of all, did the writer really want his work to fall out of publication because the heirs are making unreasonable demands on publishers?

I favor something like the life of the creator, plus 10-20 yrs.

@Matt Bernius: Also,the Gone with the Wind story highlights my concerns about the Estates. Do we know that Margaret Mitchell would have been upset or flattered?

What Dave Schuler and PD said. Time enlargements for existing works – this Sonny Bono Act – was indeed a show and a ripoff of the public, atrocious public policy. And Life+20 or so potentially leaves something behind for young dependents.

@michael reynolds:

Does any class of workers in the world have a “gig” that will benefit their “heirs in perpetuity?”

It sounds like “creatives” are asking for a rather special privilege.

If a dairy farmer’s milk strengthens a generation, why shouldn’t his heirs benefit in perpetuity?

@PD Shaw:

I favor a flat 50 from publication because it is similar to the old base + extension, and is apparent up on inspection. That is, anything “copyright 1962” would be public domain, anything “copyright 1972” would not be.

50 years also appeals because it is a long working life. If you publish your big work at age 20, you can milk it to age 70, and then it’s pd. And of course, if you are wise you might create some other works at ages 30, 40, and 50 …

(Any system with optional extension, or based on death of author, demands a “copyright search” which may fail anyway. Your lawyer may fail to find an obscure author or his date of death, and bill you anyway.)

I asked this on the other thread, but I’ll ask it here as well:

For the sake of playing devil’s advocate, why should there ever be an arbitrarily determined point in time at which you lose exclusive rights to and control over your IP? At it’s most basic, is this not a question of property rights?

@john personna:

Assuming they inherit and continue to run the farm, and that cycle continues, they DO benefit in perpetuity.

@HarvardLaw92:

Correct, but a very specific type of property. And a type of property which has historically been built on the property of others (see the Shakespeare and Disney culture remix arguments).

It has been long accepted that as with the eventual public circulation of previously patented technologies, the public domain is a tool for cultural advancement, built upon itself.

However, for a farm to run it must continue to regularly produce. A cultural property, let’s say a novel like “Catcher in the Rye”, is being reproduced and resold, but it’s not something that needs to be “worked” in order to be continually run.

This also gets, arguably, to the difference between copyright and trademark. The later, which can include characters like Micky Mouse, Batman, and Spider-man, is granted in perpetuity provided the trademark is protected (i.e. continued to be worked).

@HarvardLaw92:

Ok, so let’s look at one that is [performance] based(*). Say a doctor saved your mother’s life (before you were born). Should that doctor earn from your family in perpetuity?

* – since you did move the bar from the milk-benefit to the land-value.

@Matt Bernius:

Which, IMO, is an artfully constructed way of saying “I have decided that you have benefited long enough from ownership of your property, and since I also believe that society will benefit, I have decided to take it away from you.”

Even the takings clause prohibits the conversion of private property without proper recompense, and published works remain available the public despite the copyright remaining in force. I don’t really buy the societal benefit aspect of the argument, since the only real benefit society obtains is being able to get something for free that it previously had to pay for. It’s a thin rationalization of theft, not to put it too bluntly, and I tend to take a dim view of that.

The farm analogy wasn’t mine.

@john personna:

Again, you are approaching it from a benefit standpoint, and I don’t view it that way. Society may or many not benefit from someone’s intellectual property, but that person created the property and, irrespective of benefit, ownership of it should remain with that person.

In other words, it’s not about the benefit that the doctor provided when he saved your mother’s life. It’s about the practice that he built up in doing so. This argument strikes me as being akin to “society would be better off if we take his practice away from him and allow everybody to get medical care from him for free, because he has profited from it long enough.”

I just tend to take a dim view, in general, of arguments predicated on the basis of why something I own should effectively be seized and given to someone else, without even the benefit of recompense for the lost property, simply because that someone else has dreamed up a reason why he/she should have it. It’s mine to do with, and dispose of, as I please. If I want to release the rights to the public, then I obviously would have every right to do so, but don’t presume to tell me that I have to because you think your life will be better off if I do.

@HarvardLaw92:

That’s easy. IP is an invented abstraction. It is not a natural quantity.

That it is heavily marketed as something equivalent to natural properties is something we should view with great suspicion.

Beyond that you could look at land inheritance, primogeniture, and the like. Land has divisible limits, and this has always ensured that it keeps a useful granularity of ownership. None of us can one (and vote shares) on the farm of our great, great, great, grandfather.

There is good reason for that, and yet you are arguing that we should all hold shares in the works of our great, great, great, grandfathers, uncles, aunts, cousins, …

You are proposing madness, but madness that would not coincidentally make a great deal of good work for HarvardLaws of any year.

@HarvardLaw92:

I think you’d like us to accept “Intellectual Property” as a given, a just-so.

But it really is a service, isn’t it? I mean it may be 10 years hard work making that best selling novel, but it is WORK to be compensated.

@HarvardLaw92:

I frankly have no issues with the “life+X” argument within reason.

First, it’s hard to deny that the most endearing works of culture have been based on public domain material. Again, the Disney movie empire was built on public domain.

But beyond that, it’s also clear that copyright has been used to suppress the creative output of other individuals. In addition to the ones listed above, Lessig’s works are full of documented examples of this. Just as there are patent trolls, there are copyright trolls as well.

Again, I’m not looking to abolish copyright (for the reasons that Michael Reynolds listed above, among others). Claiming that “only real benefit society obtains is being able to get something for free that it previously had to pay for” is an example of carrying the argument to an absurd and ahistorical extreme.

Out of curiosity, do you think that patents should be held in perpetuity as well?

(I mean, really. Invent IP as an imaginary thing, and then cry crocodile tears that your invention is “confiscated.”)

@john personna:

Really? A book is an intangible abstraction? A song is? They seem pretty tangible to me.

Unless he sold or otherwise disposed of it, why not?

Madness? Don’t you think that is a bit over the top? What I’m proposing would eliminate the need for copyright attorneys entirely. It’s hardly a bit of make-work.

@Matt Bernius:

Absolutely. In the absence of a lawful taking, with the appropriate due process and recompense, there is IMO no, and I do mean no, legitimate argument for the conversion of one’s property without consent. Ever. Period.

The “society benefits” arguments are wasted on me. If society wants to benefit from my property, it can pay my price.

@HarvardLaw92:

The only way this systems works is if there was a way to identify and compensate for all IP contributions.

The fact is that profitable IP is built on the work of others. And much of that work has often lapsed into the public domain. And if the current system already depends on public domain work, then having ones work eventually reenter the system from which aspects of it were drawn seems like part of the “tax” for playing the game.

So yes, I guess that I’ll admit that it’s ultimately a taking. But given how impossible it is to imagine a system where previous property owners rights can be restored now that the genie is out of the bottle, I think it’s best to continue on the path we’re on.

Either that or, for example, a lot of people owe the Conan-Doyle estate an ass-ton of money and they should start paying. And if the system isn’t set up to restore Conan-Doyle’s rights in perpetuity, then it stands that eventually all of the derivative works based on Conan-Doyle’s creations should lapse into the public domain in order to continue to be built upon by further generations (who will in turn profit from them).

@HarvardLaw92:

Are you even trying here?

A physical book or a physical DVD are not the issue.

No, the madness you are proposing is that they content of they physical book or DVD should be attached in perpetuity to a line of errors, and that the owner of the physical book or DVD should NOT have any rights beyond simple prescribed use.

@john personna:

No. It is a thing. It is tangible property. If I write a book, then I have created a tangible thing. Likewise if I write a song or paint a painting or produce a sculpture. I have created a tangible thing, which I own, and which I alone get to control, utilize and benefit from as I see fit.

How can it be otherwise?

@john personna:

Um, no. Per first sale doctrine, once I have sold a unit to you, you can resell it further to whomever you please.

But every new unit produced? Those are mine to profit from, and yes, in perpetuity.

@HarvardLaw92:

Well, you could not reinforce what I said more directly. You simply insist, by weight of insistence, that intellectual property is a natural thing.

Tell me, in the history of man, what is the earliest example of transferable, tangible, intellectual property that you can find?

Was it immediately accepted in all lands, by all kings, parliaments, and courts? Or was it a slow spread, only actually encompassing the globe quite recently?

Lolz, but the HarvardLaws would not have us question it for a NY minute.

@HarvardLaw92:

Huh? In what system of Earth law is anyone granting you perpetuity?

@john personna:

I said it was a tangible thing. Let’s assume that I create a painting. That painting is easily identifiable as a unique creation. At what point should the ability to control the use of that unique creation cease to be mine? And why?

Copyright came about as a result of the printing press, i.e. the ability to reproduce original works and thereby abrogate the property rights of the creator of the work.

Somewhere along the way, folks like you decided that, because you can dream up some perceived benefit for yourselves / society as a whole, that taking those rights away from the creator is justifiable. It’s a monstrous rationalization.

You still haven’t told me why you think that my property should stop being my property. Why 70 years? Why not 5? If you are going to take it away from me, why wait?

@john personna:

If I own property, it remains mine throughout my life, and my property rights survive my death, in that I get to dictate what happens to the property after I have died.

What you are asserting is that some types of property can be taken away from me, without recompense, simply because you think that they should now belong to everybody.

@HarvardLaw92:

If you aren’t telling a true history of IP, why should I even bother with you?

In the beginning, there was no copyright, and paintings were copied and reinterpreted freely.

@HarvardLaw92: But you’re forgetting the fact that IP isn’t the same as tangible property. Tangible property cannot be given away and yet at the same time retained. IP, on the other hand, can be used at the same time by an infinite number of people.

That, plus the proximity of IP to being nothing more than an idea, is why we put limits on it defined by government. It’s a form of property, but the metes and bounds of the property are completely defined by government. (One thing that Libertarians ignore…) So government can define IP property rights as it pleases.

(You could use the same argument about patents: why don’t we provide infinite terms on patents?)

My other argument against long terms in copyright is if we had used to have it implemented, there are a lot of extremely wonderful operas and symphonies that would have never been written, because EVERYBODY was swiping from everybody else back in the Baroque. Mozart uses a tune by Bach as the counterpoint in an aria in the Magic Flute. Gluck swipes a wonderful aria by someone now totally obscure as the rousing send-off for Orpheus when he goes off to attack the Underworld. I think Vivaldi and Handel managed to grab tunes off each other. And so on…

@HarvardLaw92:

A particular copy of either is a tangible thing. A performance of one can be a tangible thing. The particular order of words and chords that make them up is not; they are ideas not physical things.

The only reason to grant them any protection as property whatsoever is the societal benefit derived from encouraging people to create them. Given that it is a constructed right for societal benefit, then it is entirely appropriate to judge what length of time to offer that protection based on societal benefit.

@michael reynolds:

Copyright protections didn’t begin until the 18th century and then only in isolated pockets. There was an awful lot of creative output prior to the existence of copyright, so I don’t buy that argument. Certainly some work would not be done and our culture would likely be poorer for it, so I do support copyright protections of some duration. I am not sure what the optimal length of protection would be to maximize the societal benefit, but more that 70 years seems a bit overboard.

@HarvardLaw92:

This is exactly the sort of hysterical debate style that does no one any good — and based on your previous posts — is frankly below you.

We have told you why we think your property should eventually lapse into the public domain. You just didn’t like the answer or the historical grounding of it. That doesn’t make it any less of an answer.

Further, no one here so far has suggested that a creator doesn’t have the right to profit from their creation. So statements like ” If you are going to take it away from me, why wait? ” are both the height of hyperbole and a fundamental move to mischaracterize and invalidate our position.

Good copyright/patent law should be able to balance the rewards of creation with the value for society (which is arguably easier to tangibly discuss when we are talking about things like generic drugs).

@grumpy realist:

We’ll just have to disagree. None of us are going to change our minds, which reduces it to a matter that has to be settled by the courts.I vehemently dislike the idea, and frankly support the efforts of these entities to protect their property rights by extending copyright in perpetuity. Were it me, I’d absolutely be doing the same.

@HarvardLaw92: Because historically IP did not exist. If you had tried to claim possession to the expression of an idea, people would have just laughed at you.

Remember the whole “bundle of property rights” from class? It’s ALWAYS been defined by the government.

@HarvardLaw92: What you would do is make it impossible for any artist to create anything without carrying out an incredibly detailed search to make sure his brand-new idea didn’t happen to slop over into something someone else created.

Heck, we’ve had fights over copyright infringement on quilt patterns!

Does this do anything aside from provide more employment for IP lawyers? I think not.

@Matt Bernius:

You’re absolutely correct in that I do not like the rationalization which is required to accept your answer at all.

I see the comment as being completely justified. You have taken it upon yourselves to determine the point at which I have profited enough from my work, based on your subjective determination, so why not broach the shorter option? If you have already made the rationalization that you can effectively seize my property, what prevents you from doing it in 5 years as opposed to 70? For that matter, what prevents you from doing it in 6 months, beyond that fact that you think 5 years isn’t long enough. The problem remains the underlying rationalization that you have any right to exert authority over my property to begin with.

Which is exactly the rationalization that I spoke about earlier. You’ve decided that your potential benefit justifies seizing my property. Once you have made that leap, which I refuse to make, it’s all over from a property rights standpoint. The only limitation on the extent of how you go about it becomes what you decide is justifiable. I can’t accept that, sorry. If I own it, I own it forever, or until I decide to dispose of it on my terms. You get no input into the decision, regardless of how noble you may believe your motives to be. I see it as being that simple.

This is the sort of thinking that leads to abortions like Kelo, IMO.

@HarvardLaw92:

You are being highly emotional and very absolute.

I mean, you set the minimum acceptable at something beyond any Earth copyright, and demand perpetuity.

I look at the long history, suspect that the pendulum has swung too far, and that it will swing back, but certainly without abandoning the concept of IP entirely.

@HarvardLaw92:

No. Works could be and were copied regularly prior to that. The plays of Shakespeare and Marlowe were regularly produced with no money going to their estates and sometimes with no attribution. Music since the beginning of music was regularly copied with or without attribution. All of the great works of literature before the printing press were copied and distributed either by hand or orally. The printing press did make the mass copying of particular works (books, pamplets, etc) much faster and easier, but that is a different thing.

@Grewgills:

The proper term for that activity is theft.

@HarvardLaw92:

If you have any respect for law, you’ll accept the definition of “theft” as it existed in that time and place.

Rather than simply demanding that your own personal preference be injected 400 years into the past.

@john personna:

You’re absolutely correct. As I said, if I own something, it’s mine, to do with and utilize and profit from as I see fit. For as long as I see fit. You have neither a claim to the benefits therefrom nor a voice in the decision about how that property is utilized. As far as I am concerned, copyright law is you inserting yourself into my property ownership because you have decided, based on your subjective goals, that you deserve to be included.

That I will never get behind, sorry, and I’m just like the guys the article is discussing – I’d utilize every tool in my considerable legal arsenal to prevent you from doing it. It’s really that cut and dried for me.

@john personna:

I’m pretty sure that the meaning of “theft” has been pretty consistent – taking things that do not belong to you or using them without permission.

Which, to be frank, is what you are attempting to justify.

@HarvardLaw92:

As I asked before, are you even trying?

When did Shakespeare write?

What was the Statute of Anne and when did it happen?

@HarvardLaw92:

(BTW, as I mentioned above, all my fortune was earned on copyrighted works. I’d be fine with all of you enjoying them without restriction after 50 years. Of course, as rights have mostly been transferred to corporations (where I have not explicitly placed works in the public domain) you may have some trouble finding them or their owners 50 years from now.)

@PD Shaw: “The writer should be happy for the exposure and publicity. Harlan Ellison has a humorous rant about this that’s been uploaded to YouTube.”

There seem to be two kinds of people in the world — those who find Ellison’s rants humorous and those who have met him.

@john personna:

Try to grasp this – I see no more validity in the Statute of Anne than I do in the Copyright Act of 1842 which superseded it.

There is no point, ever, in which you are justified in effectively seizing ownership of my property without recompense simply because you have decided that you can. It remains wrong, regardless of how you have chosen to rationalize the law to permit it.

Slavery, for example, has been around for thousands of years, and legitimized by the law for much of that time, but it remains wrong on principle. It’s inherently wrong.

As is taking somebody’s property simply because you have convinced yourself that you are entitled to it. We’ll just have to leave it there. I’m not going to change my mind and clearly you are not either, so we’re at an impasse. Let’s leave it there.

(It is actually hard to place things “explicitly in the public domain.” IANAL, but the law seems to treat such things as “orphans” and readily grant “copyright” to anyone who picks them up and publishes them. And so one of my old pd works could easily be your “copyright.”)

@john personna:

Which is fine. If you CHOOSE to give that away, more power to you. You get to make that decision, but don’t presume to tell me that I have to simply because you have decided that it is a good idea.

@HarvardLaw92:

lol, if you say so.

It is funny though that “HarvardLaw92” ends with a summation in total contradiction to law.

It is all about what you believe, and we should all just accept it.

@wr: I find him humorous and have absolutely no desire to meet him. (And I have nagging concern that by linking to that video that his lawyers will be in contact with me sometime in the next 10 to 20 years)

@john personna:

We’re not discussing the law so much as we are discussing a concept. People like me get paid hundreds of dollars an hour to bend the law to our desired outcome, and in this case I agree with the bending.

The underlying concept is property. I believe that property ownership is sacrosanct. It doesn’t get touched without a valid reason (due process) and without proper recompense (else we turn the law into an agent of theft). Copyright law amounts to an abrogation of both of those concepts.

You are free to believe as you see fit, and to dispose of your property in accordance with those beliefs. I would never presume to attempt to insert myself into that ownership. I am not the one presuming to dictate to you how you must conduct your property ownership. It’s quite the other way around.

@HarvardLaw92: Yes, what the Irish priests did in copying the great works of literature — what some have called “saving civilization” — was actually just theft. Because if Homer and Aeschylus and the writers of the Bible didn’t give them explicit permission to copy the works, they were just stealing it.

I know you like to brag about your status as a lawyer, and when the mood strikes you to expand that until you were a federal prosecutor — and I’m sure one of these days, we’ll here about your time on the Supreme Court — and I have no reason to doubt your every word. But your slippery slope argument is just, well, stupid. If you can’t extend copyright through eternity, then it’s also the case that we can’t set a prison term at any length because it’s exactly the same as setting it at eternity.

@wr:

Which is obviously a case of property for which ownership can not be established, i.e.abandoned property.

I’m quite sure that you can see the difference between that scenario, and one in which the property owner (and his/her heirs) are quite easily identifiable.

@HarvardLaw92: “That I will never get behind, sorry, and I’m just like the guys the article is discussing – I’d utilize every tool in my considerable legal arsenal to prevent you from doing it. It’s really that cut and dried for me.”

So the fact that this runs directly counter to what is laid out in the Constitution means nothing to you? Because that document specifically talks about “limited times” to creators.

Does your little preference now outweigh the supreme law of this land? Is that what gets you a good grade at Harvard Law? “Sure, professor, I know what the constitution says, but I think that sucks, so I win.”

@HarvardLaw92:

Guys like you first try to run roughshod over the jury, treating an invention like IP as equal to real property.

Only if that rough-riding fails will you back up and approach it with more reason.

I, while a content creator, come at it with a very different philosophy than Michael, but in the past we’ve ended up very close in argument.

An author should be compensated, and author should define the release of his works, but a rational term is not forever. It is and should be “limited” as defined in the Constitution:

50 years is a good limit.

@HarvardLaw92: “I’m pretty sure that the meaning of “theft” has been pretty consistent – taking things that do not belong to you or using them without permission. Which, to be frank, is what you are attempting to justify.”

Of course, Shakespeare took the plots of several of his plays from other works. Shall we ban all performances of Lear until someone goes back and obtains the underlying rights for Shakespeare?

Note: in the absence of copyright law, I’m the sort of person that would most probably choose to release the rights to the public upon my death. What I resent, and resist, is being told I must do so because somebody else thinks it’s a good idea. I’m a Nazi about property rights.

@PD Shaw: Don’t worry, there are plenty of other people to sue first! (Anything to keep the world from noticing you haven’t actually written anything of substance in decades…)

@john personna:

in your opinion, with which I do and will continue to disagree with. Let’s just leave it at that.

@HarvardLaw92: “Copyright law amounts to an abrogation of both of those concepts.”

Would you care to explain how your vision of those concepts outweighs that of the constitution, oh Guru of the Hundreds of Dollars per Hour?

@HarvardLaw92:

lolz, no.

Never describe the Copyright Clause of the Constitution as “just your opinion.”

@wr:

Which, again, is most probably impossible, but yes, the effort should be made before declaring per dictatem that the property has been abandoned. As I said, I am a Nazi about property rights. It’s my hot button issue.

@HarvardLaw92: So your argument is now that property rights are absolutely inviolable, as long as it’s convenient to locate the property owner?

@wr:

Would that be the same Constitution that construed blacks as being three/fifths of a person? Just asking. It’s not some infallible holy book.

@HarvardLaw92: “It’s my hot button issue.”

And yet… one for which you seem to be ignorant of the most basic facts of the law.

I can be a “Nazi” for the idea of this country being ruled by a hereditary monarchy, but as long as the constitution says otherwise, what I think is proper means nothing.

Heck, I’m not even a lawyer and I’ve got that figured out. And yet you stubbornly refuse to acknowledge the single most important fact in play here.

Actually, sometimes it’s very easy to believe you worked in the Bush justice department.

@wr:

That is pretty much the accepted state of affairs in property law, with the caveat that it’s not a matter of convenience, but instead one of possibility. If it is possible to locate heirs and substantiate ownership, then yes, that ownership should survive in perpetuity. If not, then a court has to decide who owns it based on what information is available to it.

@HarvardLaw92: “Would that be the same Constitution that construed blacks as being three/fifths of a person? Just asking. It’s not some infallible holy book.”

So you, a lawyer, a Harvard grad, and a former federal prosecutor — all by your own statements — are now claiming that pieces of the constitution you dislike are not valid as the law of the land because of other unrelated clauses that have since been amended out of existence?

If you’re tired of pretending to be a lawyer, you could just switch your screen name and pretend to be a doctor for a while. But this claiming of legal expertise while displaying the most fundamental ignorance is kind of embarassing…

@HarvardLaw92: “That is pretty much the accepted state of affairs in property law, with the caveat that it’s not a matter of convenience, but instead one of possibility. If it is possible to locate heirs and substantiate ownership, then yes, that ownership should survive in perpetuity. ”

Um, no. As we’ve just been discussing, IP ownership does not survive in perpetuity. It expires, remember?

@wr:

I am well aware of the facts of the law. I am not arguing that copyright laws are unconstitutional. I am arguing that the Constitution, and by association copyright law, is wrong on this issue. My premise is not a matter of legality – it is a matter of wrong, i.e. I see it as being wrong, therefore I resist it.

Which, again, is why I’d have no choice but to abide by the dictates of the applicable law, with the caveat that I will do my best to bend it to my benefit when I believe it to be wrong. Which is exactly what these people are doing- taking steps within the law to preserve their property rights.

@wr:

Which is exactly my premise – that rights to intellectual property should be treated exactly the same as any other sort of property.

Not ARE. SHOULD BE.

@HarvardLaw92:

I’m genuinely curious here. What limit is there if any to IP in your mind? Should every idea that pops into your head be protected? Does it need to be written down first? When does an idea become a tangible thing worthy or eternal protection? What if two people independently come up with an idea, like calculus or evolution, do they both own the idea in perpetuity? What if they can’t agree on how it is to be distributed or used?

@wr:

I said no such thing. I said that the neither the Constitution, nor the men who wrote it, were or are infallible. It can be changed when it is wrong, and in my opinion with regard to copyright and patent law it SHOULD be changed. In the interim, I have no choice but to abide by it, again with the caveat that if I can bend it to skew the situation – by arguing the matter before a court – more in the direction that I believe that it should go, then I will absolutely do so. I may lose, but it won’t be for lack of trying.

@HarvardLaw92:

Let me rephrase that for you. You are now trapped, arguing that the US constitution, and indeed the world history of intellectual property law, are wrongheaded, and only your extreme position, never actually put in practice anywhere, should be considered.

We got it.

(If you are a real lawyer, you are having a bad day.)

@HarvardLaw92: Back when you were busy being a former prosecutor, you explained that it was your job to prosecute every alleged infraction to the fullest extent of the law, allowing no extenuating circumstances whatsoever, because the law was supreme over all wishes and beliefs of man — including that of justice, incidentally.

So if a black kid is caught stealing a beer, you have a moral obligation to prosecute him to the fullest extent of the law and get the harshest possible punishment for him.

But because you’ve decided that the founders were wrong and you are right on copyright, then you will fight against the laws at every turn.

I wish I could say this was a great contradiction, but it does sound like Republican justice — the law is inflexible for that guy, but for me I can twist it any way I can.

@Grewgills:

None

If someone can convince the appropriate property registry to assert ownership, sure.

Those are questions for the aforementioned registry to determine.

When a property right is established.

Whoever establishes ownership first owns it.

File a lawsuit.

@wr:

My responsibility as a prosecutor was to advance the interests of my client – in that case the state, and I act based on the state’s determination of right and wrong.

When I bring suit in defense of my own interests, or by association when I bring suit to protect a client’s interests, I argue in defense of those interests, namely either my or my client’s determination of right and wrong as the case may be. My job is to advocate for my client’s interests. When I argue in my own interest, I am obviously protecting my own interests based on my own determination of what is right and wrong.

@HarvardLaw92: So when you said this:

“If I own property, it remains mine throughout my life, and my property rights survive my death, in that I get to dictate what happens to the property after I have died.”

what you really meant was this:

” copyright and patent law it SHOULD be changed. In the interim, I have no choice but to abide by it, again with the caveat that if I can bend it to skew the situation – by arguing the matter before a court – more in the direction that I believe that it should go, then I will absolutely do so. I may lose, but it won’t be for lack of trying.”

Yes, I’m sure that when you were issuing absolute statements on the nature of intellectual property, you were really just offering an opinion you knew contracted hundreds of years of American jurisprudence.

@HarvardLaw92: “My responsibility as a prosecutor was to advance the interests of my client – in that case the state, and I act based on the state’s determination of right and wrong.”

That, of course, is ludicrous. The state does not determine right or wrong in a criminal case — the jury does. You are now making the case that because the government brings a case, the accused is objectively “wrong.”

And as any real prosector would know, the state’s interest is in finding a just outcome, not in locking away everyone one of its agents happened to arrest regardless of subsequent findings.

@wr:

No, what I meant was:

[in my opinion], “If I own property, it remains mine throughout my life, and my property rights survive my death, in that I get to dictate what happens to the property after I have died.”

and in defense of that opinion, I’ll cheerfully go to court in an effort to ensure that things turn out the way that I want for them to.

@wr:

The state pursues a prosecution based on its opinion that a wrong has been committed, in accordance with the wrongs defined in the law. A jury, or a judge as the case may be, makes the determination as to whether the state is correct.

And we have somehow gotten grossly off-topic, and you are venturing into the ad hominem for reasons passing understanding.

Simple version: I have my beliefs about property rights, and as they concern my property, I’ll act to defend them. I may lose, but there is no circumstance in which I will not make the effort. If you wish to cede yours without making that effort, more power to you. Knock yourself out. Clear enough?

@wr:

So was Thurgood Marshall. Lose the snark.

@Grewgills:

No. Various other social and economic mechanisms were in force. For one thing, printing was rare and expensive. Royal and other governmental warrants were often in force. And the consuming market was extremely limited. You want only the rich to have books? End copyright. Copyright allows me to disperse my work to a larger audience, outside of the number of people who could afford a folio. You know what Shakespeare’s first folio sold for originally? About what an average slob might make in a year. Now you can buy a book for one hour of minimum wage.

People have always written for money. Bill Shakespeare, Chuck Dickens, Freddy Dostoevski, all of them. If writers don’t get paid, writers don’t write. We don’t work for free any more than plumbers do. Don’t let all the writerly bullsh!t deceive you. We love to pretend it’s not about money, but come around at contract time, you’ll see different.

If my publisher can’t have an exclusive, my publisher doesn’t pay me. If I can’t offer my publisher an exclusive I’ve got nothing to sell, and I go do something else for a living and literature, art, dance, theater, movies, TV, all of it dies.

@HarvardLaw92:

You have left the ground of your original assertion here. You previously opined that any work created was property and it’s rights SHOULD be inviolable. With this new formulation, whatever the law decides is property is property.

Using your formulation, if we made it impossible to establish IP as property then no idea SHOULD be protected. Since property right could not be established then no idea would ever become tangible thing. Continuing on in this vein, all of the great national epic poems or any ancient work of art is or was tangible, but the latest pop song is tangible.

@Grewgills:

No, one is what I believe. The other is what is necessary to effect those beliefs within the context of existing law.

As I told Wr elsewhere, were it within my means, I would amend the Constitution to undo the provision for copyright and patent limitations and make them survive in perpetuity.

Since it is not within my means to do so, I am tasked with using the existing law and system in such a way that things turn out the way that I want for them to turn out. I think the Constitution is wrong on this issue, but it remains the Constitution. Since I can’t change it, I’m left with getting around it when I think it’s wrong.

@HarvardLaw92:

No.

Stealing a painting is theft. Copying a painting is forgery.

Stealing money is theft. Copying money is counterfeiting.

Stealing parts of a book is theft. Copying parts of a book is plagiarism.

I’m pretty certain that you understand the difference.

@PJ:

And I am pretty sure that you understand all of those to be varieties of theft. No need to split hairs in search of a non-existent distinction.

Great comment thread.

I’m not sure what damages are suffered by the author when the buyer of a book copies and sells his copies, unless there’s some government grant of exclusivity. Aren’t Mr. Author your damages solely a result of competition? The trip into the public domain is the deal you get in exchange for the government’s franchise of the exclusive right to copy your idea for a limited time.

@HarvardLaw92:

No, theft includes me actually taking what you have.

If you scribble some notes on a napkin and I copy them, you still have your original notes. I didn’t steal them.

(Nor do I steal your soul if I take a photo of you.)

@HarvardLaw92:

I don’t think I would.

Let me establish first of all that I own or co-own copyright to about 100 books (round numbers). I have a dog in this fight.

The reason I differ is that IP is not the same as real estate, let’s say. I create it in order to sell it for money. Let me be clear on that. But I also create it knowing that what I write will live on in the minds of the people who read my books. Call that a secondary benefit for me: I get to influence people. I’m creating ideas that will affect people’s lives. I get my little shot at immortality. I contribute to civilization.

Were I to insist on my books being controlled absolutely by my heirs I’d risk losing that secondary benefit. To put it simply: I want the money, but I also want the effect. Copyright lets me have both. I get paid, but at some point I concede that what I created now belongs at least partly to my readers. And I want that. Most writers do. In fact, I’d venture that 99% of us do. Like most writers (and artists more generally) I know I get to do what I do because greater men and women than I have contributed their IP to the big pool of knowledge.

What’s required is a balance between what I need (to get paid) and what the broader civilization needs (to learn.)

@michael reynolds:

And I respect that, which is why I have taken pains to assert that this is my belief, applicable to my property. What other people choose to do with theirs neither affects nor concerns me. I just get testy when they start advancing plans for what is mine instead of sticking to concerning themselves with what is theirs.

I should also say that I have no dog in this fight, as I am neither a copyright nor a patent holder, but on face the concept of taking someone’s property, irrespective of the nature of that property, in the interest of some nebulous sense of the greater good just doesn’t sit right with me. That’s it, in a nutshell.

@michael reynolds: Not only that. Having to find the heirs of Bram Stocker to write a story about Dracula would be a pain for any writer.

@HarvardLaw92:

I’m curious, are your views on software patents the same? Drug patents? Gene patents?

@michael reynolds:

Shakespeare, Marlow, et al were paid once for a play. They did not receive royalties every time it was performed and certainly didn’t when they were copied (a regular occurrence ). Bards and skalds were paid (often poorly), but once they sang or told a story anyone that heard it and could remember it could then repeat it without benefit to the original author. Going back way further, cave painters didn’t receive royalties when someone copied their picture of a buffalo.

Until very recently art was paid for once if at all, yet art has always been with us. I think copyright has contributed to the profusion of good art and literature and certainly the film industry could not continue to make blockbusters or most movies without copyright protection, That said, if copyright law disappeared tomorrow art would continue on as it did before copyright law existed.

It would shrink the market considerably by removing a large chunk of the profit motive as I acknowledged earlier, but art would continue on. Music, theater, dance, visual arts all existed before copyright type protections. Playwrites, composers, etc, even or maybe especially the greats, stole shamelessly from their contemporaries and those that came before them.

The Renaissance bloomed without such protections and part of that blooming was because of the free exchange. Science, art, and life in general benefits from more, not less, free exchange of ideas.

We have to weigh the societal benefits of protecting ideas to profit those who come up with them, so that they continue to come up with them, against the benefits to society of a more free exchange. It is no easy trick to weigh those against each other and come to an ideal number of years for copyright or patent protections. At this point, I think the pendulum has swung to far in extending copyright and patents and the period could do with a bit of shortening. From your earlier comment, I don’t think you disagree or not by much.

@PJ:

My view is pretty consistently that property is property, and before you propose to take it away from someone, regardless of how noble you may believe your rationale for doing so may be, you should have a constitutionally defensible rationale which satisfies due process AND you should be required to pay me fair market value for it.

So yea, any of those are intellectual property to the extent that they are the original product of the person asserting property ownership.

Authors shouldn’t be worried about X+Y years becoming Y-Z years or whatever. What they should be worried about are e-readers, tablets and smart phones, and desktop hard disks that within a few years will be able to store the modern version of the Library of Alexandria.

The X+Y years will at most make sure that others can’t legally make money on their work. (If an entity has deep enough pockets and enough lawyers that’s not going to be true either…)

@Grewgills:

Dude, if what you’re trying to do is justify your theft of books and music via torrenting, don’t bother, I don’t really care.

But is there not some part of you that is just a wee bit uncomfortable lecturing an actual writer – a writer who knows a whole lot of writers personally, who in fact is married to another writer – about what does and does not motivate me/us to do what we do? That doesn’t strike you as a bit hubristic?

What preceded copyright was the sponsorship of the wealthy. That’s how your Renaissance artists got paid. If you want to go back to literature, art and music existing only for the privileged few, then do away with copyright. I’ll write for some rich kids, and the poor kids can drop dead. Because that’s where you’re going with this.

You don’t know what you’re talking about. I actually do. What with this being my actual job and all.

@michael reynolds:

I’m not attempting to justify anything, nor am I speaking exclusively about writing. I am talking about all intellectual property, whether it be artistic, scientific, or otherwise. As such I do have a dog in this fight as well.

Shakespeare didn’t enjoy copyright protections, yet plenty of the poor attended his plays and laughed at the fart jokes.

You are responding to me as though I am advocating removal of all copyright protections rather than advocating for a shorter than 70 year period of protection. I seriously doubt that artistic output would be seriously impacted by copyright protections being shortened to say 40 years after publication.

@PJ:

We’re already there.

@PJ:

Provided the content has been digitized and released in some backwards accessible format. PS… Support the Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

@Grewgills:

Don’t think so.

Google estimated that there had been about 130 million books published up and until 2010.

0.5MiB to store each book, so 65 million MiB or about 62TiB to store all of them. (Obviously without any images which would take up far more space than text.)

@PJ:

In terms of storage side, it entirely depends on whether the books can be represented as flat text files versus page scans*. But generally speaking you’re on the right track.

* – further we can get into arguments about whether flat text accurately represents traditional books (especially as we get to ones whose typography and other physical features are tied to their overall experience).

@Grewgills:

Not completely true… Shakespeare, Marlow, and others of their day, were on retainer from specific theater troupes (often they were also actors in those troupes). So it wasn’t simply work for hire. And in many respects they did receive money from each performance that their players did of their plays. Trying to compare the economics of that time to the modern royalty system is an exercise in anachronism.

That said, on the flip side @michael reynolds: :

Completely agree, but it’s worth noting (and it doesn’t disprove your point) that all of those individuals (and frankly every US writer before 1978) worked in a much weaker copyright system than exists today. And yet they continued to write.

The point I take away from this, and I completely agree with, is that creators, at the very least, need to be able to (a) get paid, and (b) have defined control over their work.

@HarvardLaw92: ” regardless of how noble you may believe your rationale for doing so may be, you should have a constitutionally defensible rationale”

But there is a constitutionally defensible rationale — the very one that is specified in the constitution and that you keep comparing to slavery.

Either the constitution holds sway here or it doesn’t. You can’t claim the literal words of the document are so wrong they’re tantamount to slavery and then say “if you want to end a copyright you need a constitutionally definsible rationale.” Either the constitution is a pile of puke and we should all be free to pick and choose those areas we think work, or we can fall back on it to claim its authority. We can’t really do both.

@PJ:

A good tablet with a good memory card can only hold about 350 thousand or so books. That certainly rivals the ancient Library of Alexandria and perhaps exceeds it. It is more than I will ever read for certain. Consider that tablet, laptop, phone, or whatever has internet access that allows one to exchange what is on said devise pretty quickly and we have already gotten to the point that for practical purposes, people have access to a substantial portion of all of that material. What is slowing that down more than memory at this point is how many of those books have not yet been digitized.

It is rather amazing that I could go onto Amazon today and buy enough memory to store every book ever published, although many of them have yet to be digitized.

@wr:

Constitutionally defensible in terms of due process and recompense. As far as I am concerned, the 5th Amendment overrides the copyright clause, so once you are prepared to pay me FMV for any asset that you propose to convert, then we’re golden. After all, the 5th doesn’t distinguish between tangible and intangible property. It simply stipulates private property.

And it mandates just compensation.

But, feel free to advance an argument as to why said amendment doesn’t apply, given that you seem to have determined yourself to be a better lawyer than I am.

@wr:

This gets to a core aspect of @HL92’s argument. In his very words, he’s a Property Nazi (which honestly, isn’t something anyone should say).

So he’s staked an binary moral claim that limited copyrights = evil. Therefore, it allows him to substitute any other evil thing in for “limited copyrights.” Hence we get to slavery — which is smart rhetorical move because it essentially sinks battleships.

For although we can point to the fact that every copyright statue to this point has, at the very least, tacitly expressed a social good by limiting copyright, its also true that there were countless government docs over the same time (including the Constitution which contained both) that also facilitated slavery.

And to some point, @HL92 is right, laws and morals change. Its entirely possible in the future that limited copyright goes away. But that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a grounded moral argument for limited copyright. Just as there are grounded moral arguments for slavery. Its just those have, thankfully, gone out of favor.

However, the fact remains that, at least for the moment, the moral argument for limited copyright continues to lead in the public and legal debates (though I’d argue it has lost ground). Who knows what will come in the future.

@HarvardLaw92:

Serious question… by applying for copyright protection are you not also inherently agreeing to the legal stipulations of copyright? If that is the case, it seems like the 5th Amendment’s seizure provisions (I’m assuming you’re referring to the final bit in particular) seem like a bit of a threat.

That said, I appreciate that lawyers think differently about these issues than lay folks.

@Matt Bernius:

They did receive money for additional performances, but only received that money if it was their troupe that performed the work. They regularly borrowed heavily from each other and felt no need to reward the original author they borrowed from. My point was that there was no real protection for those actor/playwrites against another taking their work, making minor cosmetic changes and rereleasing it. As there were no real protections for Mozart and his contemporaries if other composers used what they created for their own works. Somehow without those protections, art still thrived.

Of course the economics were different and not directly comparable, but to say that art would die minus copyright protections is more than a little hyperbole.

That I agree with and we have much more of that now than at almost any point in history. Digital sharing has eroded that somewhat, but artist protections are still stronger now than they were 100 years ago. Go back much further and an artist’s control of their work was negligible as was their ability to collect more than once absent being paid to perform it again.

@Matt Bernius:

No. I’ll have to dig to find the specific case, but generally speaking government can not predicate the extension of a statutory benefit on the ceding of a constitutional right.

@Grewgills:

Right. Further, the troupe was typically rotating multiple of their works at a given time. And, if we’re being totally exact, since texts weren’t exactly public (at least not as they are today), when someone stole one of Shakespeare’s plays, they were getting the plot and only as many lines as could be remembered. It wasn’t a wholesale stealing (though it would have fallen under modern copyright protections).

Agreed, and the fact is culture is to some degree better for it. For example, Marlowe’s Faust would literally not have been possible without “liberally borrowing” from in-process translations of the German Faust chapbook as Marlowe was dead by the time the first printed English translations were available.

Perpetual IP is rather like the pure libertarian ideal, isn’t it? It is something that works well in fantasy, is so far from workable that it has never and will never be tried, but still allows fanatics to clog discussion and pull everyone away from pragmatic or rational concerns.

Speaking of pragmatism,

That from What We Know, What We Don’t Know, and What Policy-makers Would Like Us to Know About the Economics of Copyright

@john personna:

It’s more like the legal ideal. The courts have been clear that the takings clause of the 5th Amendment is equally applicable to intangible property.

Congress has clearly stipulated that intangible property, a patent for example, is personal property for the purposes of legal proceedings. Water rights are as well, so the question of whether or not a copyright represents a property interest isn’t arcane – based on settled law it isn’t even a question. A personal property right exists with respect to holding a copyright.

Now, as I said already, the 5th Amendment is clear that private property may not be taken without due process and just compensation (which is interpreted by the courts as the value lost to the owner, not the value gained by the taker).

So, just pay up FMV when you terminate a copyright and everybody will be happy.

@HarvardLaw92:

Dude, do you know that technology only processes because IP expires?

At one point the Wright Bros patent on wing warping was interpreted to cover all aircraft.

It is fantasy to think the Wright family, with perpetual IP would have licensed to all competitors. Monopoly brings stagnation.

We already have, with the recent IP explosion, the coining of “tragedy of the anti-commons.”

Add 3 generations and you have the technological gridlock of the anti-commons.

@HarvardLaw92: “But, feel free to advance an argument as to why said amendment doesn’t apply, given that you seem to have determined yourself to be a better lawyer than I am.”

Oh, wow, man. You really got me there. You’re like so smart and all so I could never come up with an argument against yours.

Oh, wait. Maybe this one:

There is not a court in the entire country, or a standing legal decision in our history, that supports your view.

Copyrights expire after a certain period.

And in fact, the idea that no longer extending the protections of the government is somehow equal to a “taking” means that we are legally obligated to send the army in to protect anyone who lives in Kansas from Indian attacks, since we once did, and to remove that protection would be an unconstitutional “taking.”

Dude, I am not a laywer and I can see how silly your arguments are. Stop digging.

Would you be comfortable with Bell as the only cell phone maker, and lugging your brick?

@wr:

The sad thing is that his world doesn’t even make sense. No one would want to live there.

@john personna:

Technology progressing isn’t my problem. If you propose to take property, then pay up. Simple proposition.

@HarvardLaw92:

Again you reinforce what I say above, you are indulging in fantasy.

No one wants a world limited to Bell brick phones, or one where those kids who were to form Apple couldn’t secure rights to make a digital computer.

Back up further and “computer chips” might not happen, it would depend in how widely Shockley decided to license the transistor.

@wr:

Um, no. In fact, the relevant court for this very area of law, the Federal Circuit, supported my view in Huntleigh USA Corp. v. United States. The takings clause is applicable to real, personal AND intangible property.

Congress was explicit in 35 USC 261 that patents, despite being intangible, are to have the legal attributes of personal property. Water rights, just as an example, have been litigated as tangible property in a multitude of lawsuits as well, so this argument that I am making is not off the wall. It is one that Congress itself, and the courts, have already explicitly made for me.

Now, this puts you into a box, because irrespective of whether we consider copyrights to be intangible property or tangible personal property, per the court that determines these matters, the 5th Amendment still applies (per Huntleigh).

Now, if you think they are wrong, by all means, again, feel free to advance a legal argument, but climb down off of your “I know more about the law than you do” high horse. You don’t.

I’ll be waiting for your enthralling argument concerning why the 5th Amendment takings clause doesn’t apply to copyrights. By all means proceed.

@john personna:

Which is an emotional argument that I assure you I do not care about in the least. You are wasting your time going that route.

When I am fairly confident that I can convince a court that I have a property right to protect inherent in a copyright, and I am, then the societal benefit is immaterial to the concept that you can’t take it away from me without payment. It’s that simple.

Because, after all, if there were no value inherent in the copyright, then there would be no benefit for society to glean by virtue of it being terminated.

Come to think of it, I have been a tad bored lately. I think I’ll go client shopping and see if there is a case to be brought here.

@HarvardLaw92:

Actually is is not at all emotional to balance between needs of current and future innovators. It is a rational discussion as old as IP itself.

People want progress, and the big selling point of IP is that it yields rapid progress.

Of course as we have seen it only does that when inventors, or their heirs cannot block competition in perpetuity.

@john personna:

For the 9000th time, by all means, terminate copyrights. Congratulate yourself on whatever societal benefit you feel has been accomplished. I’ll even stipulate (despite not remotely giving a darn) that there is some sort of benefit to society to be found.

The seizing party, government, just has to pay up. You don’t get to seize property for nothing, no matter many ways from Sunday you have convinced yourself that it will benefit society. The constitution is pretty clear about that one.

@HarvardLaw92

So we have another crazy fantasy. Right now most works, probably 99.9% of copyrighted works, exit their term with no monetary value. But you know, if government was paying, those heirs would want some. So what do you do, some giant bureau to value worthless works?

And I guess a court has to decide when someone claims that there will be a remake 10 years from now?

Maybe your game for the day is to see if you can make a case for the ridiculous.

Will you go to court to claim Mork and Mindy is worth $50M?

Maybe the Galloping Gourmet will have a revival, with merchandizing! $200M!

@john personna:

If there is no monetary value, then you have nothing to lose by acknowledging the property right (which you seem to implicitly be doing), now do you?

We already have a “bureau” that deals with 5th Amendment takings. We call it the federal court system.

This is where those corporate finance classes come in handy. Just extrapolate the earnings stream over the life of the copyright forward in perpetuity, with a sensible inflation rate, and price that value in current dollars. Simple TVM, and computers make it easy. The courts get involved if the property holder disagrees with the figure and an impasse develops.

That said though, simply calling it a “crazy fantasy”, without addressing the legal points that have been made, sort of tells me that you dislike the argument, but you can’t rebut it.

Tough room …

@john personna:

No, it was partly to test this argument out, by roping you into challenging it, and partly to just tweak your nose a bit (because I enjoy it).

It helps me refine my thinking and it amuses me. I’d say that both objectives were achieved.

@HarvardLaw92:

So if [Mork] and Mindy makes no money for its second fifty years, you would value it at zero?

And then if someone kept on the freed version to do a remake?

I think you have some internal contradictions. You can’t actually compensate for future use.

@HarvardLaw92:

I would call this thread an epic fail for you then, given the corners you have had to retreat to.

Brick phones and a government bureau to calculate the value [of] all expiring IP. Epic.

@HarvardLaw92:

The only reason property rights of any kind exist is for societal benefit. Arguing that societal benefit doesn’t matter when determining how long and how far those rights extend is ridiculous.

@john personna:

Who says that I can’t?

@Grewgills:

I simply stated that societal benefit doesn’t matter to me. I’m prepared to stipulate that there is some nebulous concept called societal benefit which exists, if you are prepared to stipulate that there is indeed a property interest inherent in intangible property like a copyright.

@john personna:

Of course you would, but you still haven’t rebutted my property argument. I get that you dislike it. I just don’t care.

@HarvardLaw92:

If societal benefit doesn’t matter, then no legal rights matter. Property rights exist for the benefit of society, not for any other reason that I have seen defended without resort to circular arguments.

@Grewgills:

I would say that property rights exist for the benefit of the individual, since it is his/her right that is being protected. Society doesn’t own property. It may indirectly benefit from the utilization of property, but the underlying right of ownership belongs to the individual. Consider that the 5th Amendment conditions the ability of society to take property from the individual on due process. It protects the right of the individual against arbitrary expropriation.

@HarvardLaw92:

Can you point to any place at any time that protected intellectual property to the degree that you think it should be?

@Grewgills: