On the Number of Parties 2: Basic Counting, Part 2

This time: some multi-party examples.

Ok, so part 1 of this series detailed some overall terminology and took a look at two cases of single-seat plurality elections which have long been dominated by two parties (but in by no means identical ways): the US and the UK. This installment will look at two cases of clear mutlipartism: Germany and Israel. Germany uses Mixed-member proportional representation (MMP) and Israel uses closed-list proportional representation (CLPR) with seats assigned using the D’Hondt method of highest averages. (In the interest of space I am not going to go into grand detail here about how these systems work, although links to basic definitions have been provided).

Both systems are parliamentary, i.e., the government is formed by the party or coalition of parties that command a majority of the legislature. The Prime Minister (or, in Germany’s case, the Chancellor) is an elected member of parliament and the cabinet is formed by the majority party or coalition of parties and must maintain the confidence of the majority to remain in power. Each country also has a president who serves as the head of state. In Germany, the president is elected by a convention that represents the Länder (German states). In Israel, the president is elected by the Knesset. In both cases, the role is largely ceremonial.

Germany

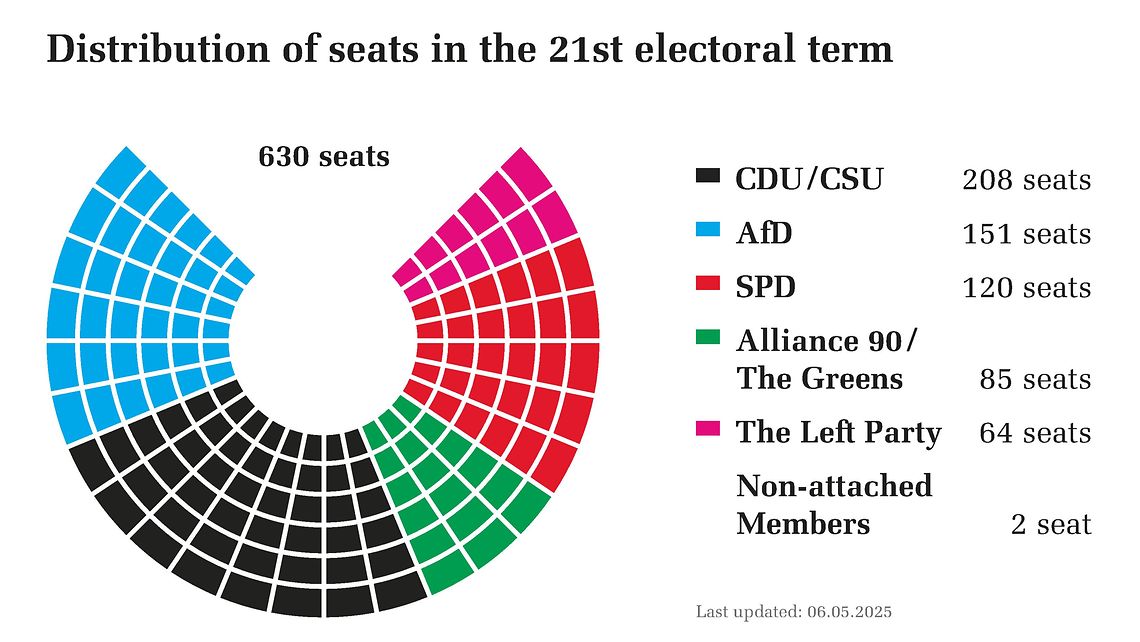

Here’s the seat distribution of Germany’s Bundestag as a result of its 2021 election. Here we see six parliamentary parties (and two independents). There were a total of 47 parties that ran in the election (and 54 total qualified to run).

Note that the CDU and CSU caucus together (they are essentially the same party that uses different labels in different parts of the country).

So, seven parliamentary parties and 47 electoral parties.

Quite clearly, this is a more multi-party system than we saw in the UK.

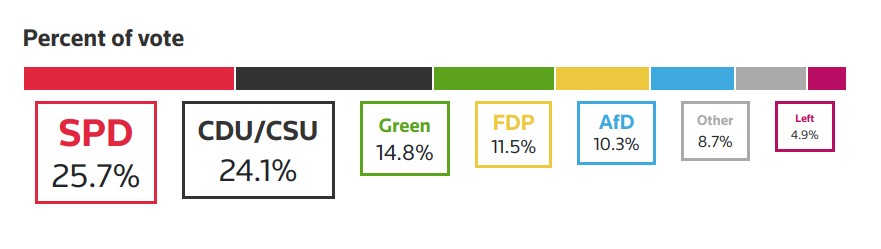

Here are the preliminary vote distributions (i.e., not the final official numbers) by party:

Note that “other” accounts for 41 parties.

A quick run-down of comparing the seat distributions and those preliminary numbers show that the system is pretty proportional (obviously if I pulled the final data the numbers would be more accurate, but this is close enough to illustrate the point):

| %Seats | %Votes | ||

| SPD | 206 | 27.99% | 25.70% |

| CSU/CDU | 197 | 26.77% | 24.10% |

| Greens | 118 | 16.03% | 14.80% |

| FDP | 92 | 12.50% | 11.50% |

| AfD | 82 | 11.14% | 10.30% |

| Left | 39 | 5.30% | 4.90% |

| Ind | 2 | 0.27% | |

| 736 |

Note that unlike in the UK, it is impossible for any party to govern by itself. Indeed, the SPD ended up forming a coalition with the Greens and the FDP, as announced earlier this month. Via the NYT: A new era: Germany meets its post-Merkel government.

For the first time in 16 years, Germany will have a center-left government and a new chancellor, Olaf Scholz, a Social Democrat, whose job will be to fill the shoes of Angela Merkel, the woman who made Germany indispensable in Europe and the world.

After much anticipation, Mr. Scholz and his coalition partners from the progressive Greens and the pro-business Free Democrats stepped in front of the cameras on Wednesday to announce a 177-page governing deal they have negotiated under strict secrecy since the Sept. 26 election.

The WaPo piece on German Election 2021 discussed various coalitional possibilities if anyone wants to see how different combinations were possible.

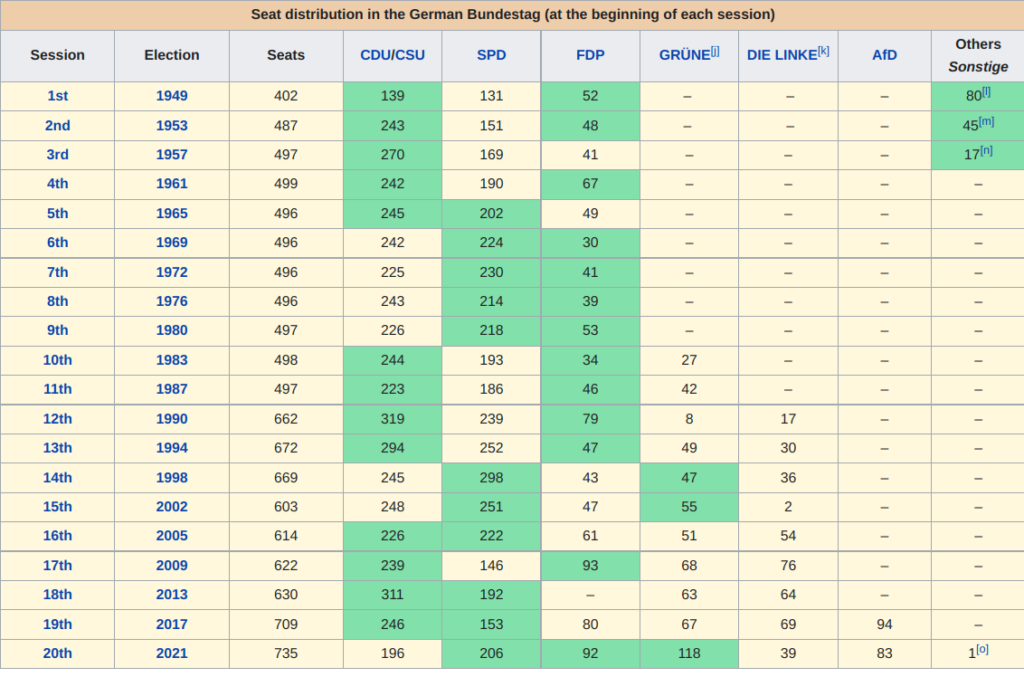

This seat distribution is reflective of the ongoing evolution of Germany’s party system. As illustrated below, the dominance of the SPD and CDU/CSU has diminished over time. First, note that coalition government (the green boxes) has been the norm, but that system used to give either the SPD or the CSU/CDU a large enough seat share that it only needed one partner (the FDP usually being the beneficiary). We can also see the formation of the Greens and Die LInke (the Left) in the 80s and 90s, respectively, and the Greens’ growth in recent years. Also note the emergence of the nationalist right party, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) in 2017. Here we see how space (i.e., a proportional system that allows smaller factions of voters to still be represented) for new party formation from both the left and the right can lead to new parties emerging instead of fringes trying to take over existing parties.

Israel

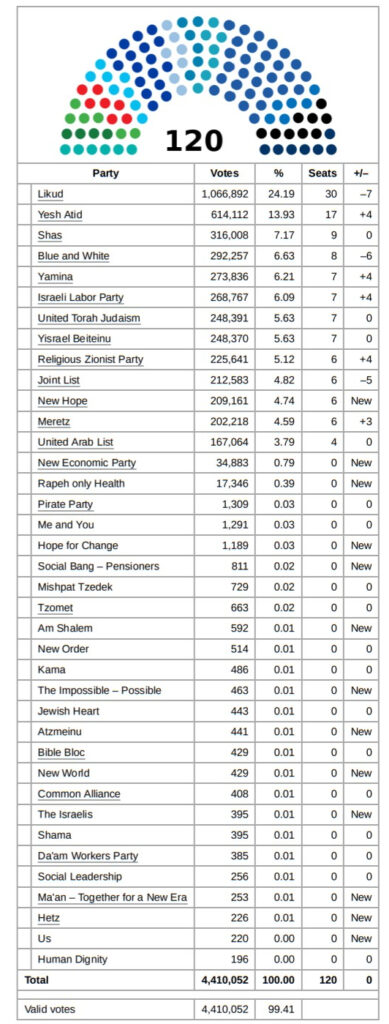

Here is the Knesset, Israel’s unicameral legislature, from its most recent election. There are 13 parliamentary parties. It is worth noting that no party has anywhere near the majority needed to control the 120-seat body outright. A coalition is clearly required to govern Israel.

There are a total of 39 electoral parties.

If like above, we compare seat and vote percentages, we can see that Israel’s system is quite proportional:

| Seats | %Seats | %Votes | |

| Likud | 30 | 25.00% | 24.19% |

| Yesh Atid | 17 | 14.17% | 13.93% |

| Shas | 9 | 7.50% | 7.17% |

| Blue and White | 8 | 6.67% | 6.63% |

| Yamina | 7 | 5.83% | 6.21% |

| Israeli Labor Party | 7 | 5.83% | 6.09% |

| United Torah Judaism | 7 | 5.83% | 5.63% |

| Yisrael Beiteinu | 7 | 5.83% | 5.63% |

| Religious Zionist Party | 6 | 5.00% | 5.12% |

| Joint List | 6 | 5.00% | 4.82% |

| New Hope | 6 | 5.00% | 4.74% |

| Meretz | 6 | 5.00% | 4.59% |

| United Arab List | 4 | 3.33% | 3.79% |

A list of cabinet members and their party affiliations can be found here. There are seven parties in the cabinet. As a Reuters’ report described it:

Israel’s new government is a hodgepodge of political parties that had little in common other than a desire to unseat veteran right-wing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

The coalition, sworn in on Sunday, spans the far left to far right and includes for the first time a small Islamist faction representing Israel’s Arab minority.

I would note that for all the obvious challenges presented by such a cabinet, its makeup makes sense insofar as it reflects the diversity of the Israeli electorate–after all, it took four elections in two years for the population to produce outcomes that could result in a government being formed. While hardly ideal, consider that such a circumstance at least is reflective of the overall level of disagreement in the populace, and has forced compromise in the formation of the national government, rather than allowing a minority faction of the citizenry to have outsized power.*

Note that Likud has the most seats (but still only 25%), but was unable to assemble a viable majority of the Knesset to form the government.

Next up: beyond just a raw count.

*Update (1/22/23). In looking back at this, I would revise this statement, but rather than changing the text, I will add this footnote. Coalition government can, and often does, elevate the influence of a given coalition partner above its relative size (which might be, in fact, “outsized power” depending on the definition of the term). What I was trying to get at here is that at least in coalition formation, the process is one of having to build a majority to govern (and a majority that can be punished at the next election) as opposed to the US system wherein the minority often can thwart governance, especially in the Senate, without having to be part of a constructed majority at all. There is an important difference between being a minority partner who is part of a majority coalition and being a minority actor with a veto without having any connection whatsoever to a governing majority.

I’m not sure where you are getting this. Israel is an absolutely textbook example of a system of governance that has led to tiny minorities having extremely outsized power, warping the state itself into essentially an apartheid regime. And not just with respect to the Palestinian issue. Marriage, divorce, segregation by sex, and on and on. Policy after policy enacted against the wishes of the vast majority.

@MarkedMan: The rather narrow point I am making is that unlike, say, the US Senate, the party that represents fewer people doesn’t have more power than the party that represents more people.

I am certainly willing to accept that Israel is from perfect on the democracy front, especially as it pertains to Palestine. I would need more details about some of the other issues you list and certainly am willing to revise my assessment as is appropriate.

While I really am not especially interested in turning the thread into one about Israel, per se, could you tell me, for example, a rule about marriage, et al. that is enacted against the wishes of the vast majority?

@MarkedMan: And to maybe head off some of this:

1. I picked Israel as a clear example of a multi-party system.

2. I stand by the notion that their electoral system is more representative than the US’s.

3. That doesn’t mean that I am suggesting Israeli policy nor Israel’s institutions are beyond criticism.

So, thinking about the marriage thing: I can see clear objections to Israel’s structure of marriage (and, beyond that, several ways in which religion influences the state). The question for me is the issue of what degree does that violate majority preferences (especially vast majorities). I simply don’t know.

I will also note that given the fragmented nature of Israeli politics that certain change is probably impossible because, yes, small parties might have a veto (but that is different than what you are criticizing me for above, or so I would argue).

Marriage is controlled completely by highly conservative religious authorities who decide the criteria for sanctioning a marriage and then are granted sole power to decide who meets that criteria. It is wildly unpopular with the vast majority of Israelis, but continues because the nominally ruling party needs the votes. Note that these extremely conservative Religious authorities also control divorce, granting it according to arcane and highly unpopular religious rules. These are just a few examples, but there are many more.

You know your field so I accept that parties are more likely to get seats in the Knesset. But I honestly thought you were going use Israel as an example of how that representation can go completely off the rails unless… something. To me Israel is the nightmare example of how a democracy can be structured (or evolve or both) to give tiny minorities outside control over the vast majority of the population.

@MarkedMan: I was primarily using Israel as an example of lots of parties.

And yes, there is a very strong argument to make that it creates too much fragmentation in the party system. I did pick it as an extreme example of multi-party systems.

This may be an example of non-overlapping interests. To me, the number of parties is not important, rather the quality of the resulting governance. However, I recognize that is part of your area of study.